| Skull Tower | |

|---|---|

Detail of a tower wall | |

| Location | Niš, Serbia |

| Coordinates | 43°18′44″N 21°55′26″E / 43.3122°N 21.9238°E |

| Built | 1809 |

| Visitors | 30,000–50,000 (in 2009) |

Location of Skull Tower in Serbia | |

| Type | Cultural Monument of Exceptional Importance |

| Designated | 6 May 1948 |

| Reference no. | SK 218[1] |

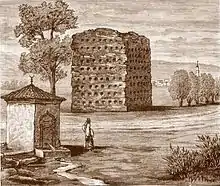

Skull Tower (Serbian Cyrillic: Ћеле кула, romanized: Ćele kula, pronounced [tɕel̩e kula]) is a stone structure embedded with human skulls located in Niš, Serbia. It was constructed by the Ottoman Empire following the Battle of Čegar of May 1809, during the First Serbian Uprising. During the battle, Serbian rebels under the command of Stevan Sinđelić were surrounded by the Ottomans on Čegar Hill, near Niš. Knowing that he and his fighters would be impaled if captured, Sinđelić detonated a powder magazine within the rebel entrenchment, killing himself, his subordinates and the encroaching Ottoman soldiers. The governor of the Rumelia Eyalet, Hurshid Pasha, ordered that a tower be made from the skulls of the fallen rebels. The tower is 4.5 metres (15 ft) high, and originally contained 952 skulls embedded on four sides in 14 rows.

In 1861, Midhat Pasha, the last Ottoman governor of Niš, ordered that Skull Tower be dismantled. Following the Ottomans' withdrawal from Niš in 1878, the structure was partially restored, roofed over with a baldachin and some of the skulls that had been removed from it were returned. Construction of a chapel surrounding the structure commenced in 1892 and was completed in 1894. The chapel was renovated in 1937. A bust of Sinđelić was added the following year. In 1948, Skull Tower and the chapel enclosing it were declared Cultural Monuments of Exceptional Importance and came under the protection of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Further renovation of the chapel occurred again in 1989.

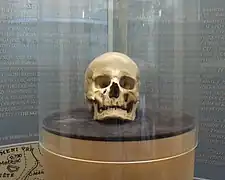

As of 2024, 58 skulls remain embedded in Skull Tower's walls. The one that is said to belong to Sinđelić is enclosed in a glass container adjacent to the structure. Seen as a symbol of independence by many Serbs, it has become a popular tourist attraction, visited by between 30,000 and 50,000 people annually.

History

Construction

The First Serbian Uprising against Ottoman rule erupted in February 1804, with Karađorđe as its leader.[2] On 19 May 1809, 3,000 Serbian rebels under the command of Stevan Sinđelić were attacked by the Ottomans at Čegar Hill,[3] near the village of Kamenica, in Niš.[4] The rebels were plagued by lack of coordination, largely due to the rivalry between commanders Miloje Petrović and Petar Dobrnjac. As a result, Sinđelić's fighters failed to receive support from the other rebel detachments.[3] The numerically superior Ottomans lost thousands of soldiers in a number of failed attacks against the rebels, but eventually overwhelmed the Serbian lines. Knowing that he and his men would be impaled if captured, Sinđelić fired at his entrenchment's gun powder magazine, setting off a massive explosion. The resulting blast killed him and everyone else in the vicinity.[5][6][7][8]

After the battle, the governor of the Rumelia Eyalet, Hurshid Pasha, ordered that the heads of Sinđelić and his men be skinned, stuffed and sent to the Ottoman sultan, Mahmud II. Upon being viewed by the sultan, the skulls were then returned to Niš, where the Ottomans built Skull Tower as a warning to residents contemplating rebellion.[7] The Ottoman Empire was known to create tower structures from the skulls of rebel fighters in order to elicit terror among its opponents.[9] Skull Tower was constructed on the road from Istanbul to Belgrade.[10] It was built of sand and limestone.[11] The structure is 4.5 metres (15 ft) high.[12] It originally consisted of 952 skulls embedded on four sides in 14 rows.[7] The locals named it ćele kula, from the Turkish kelle kulesi, which means "skull tower".[5]

The French Romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine visited the tower while passing through Niš in 1833. By that time, the skulls had already been bleached from exposure to the elements.[11] "My eyes and my heart greeted the remains of those brave men whose cut-off heads made the cornerstone of the independence of their homeland," de Lamartine later wrote. "May the Serbs keep this monument! It will always teach their children the value of the independence of a people, showing them the real price their fathers had to pay for it."[7] De Lamartine's account attracted many Western travellers to Niš.[11] Skull Tower was also mentioned in the works of the British travel writer Alexander William Kinglake, published in 1849.[13]

Dismantling and conservation

In the years following its construction, many skulls fell out from the tower walls, some were taken away for burial by relatives thinking they could identify the skulls of their deceased family members, and some were taken by souvenir hunters.[14] Midhat Pasha, the last Ottoman governor of Niš, ordered that Skull Tower be dismantled in 1861.[10] He realized that the structure no longer served as an effective means of discouraging potential rebels and only fostered resentment against the Ottomans, reminding locals of the empire's cruelty.[15] During the dismantling, the remaining skulls were removed from the tower.[10]

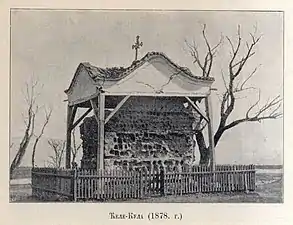

After the Ottomans withdrew from Niš in 1878, the Royal Serbian Army scoured the town and its surroundings in search of the missing skulls. One was found embedded deep inside the tower walls and sent to the National Museum in Belgrade. This was followed by the construction of a roof baldachin, which was topped off with a cross. This is how the structure is depicted in an 1883 painting by the realist Đorđe Krstić. In 1892, work commenced on the construction of a chapel that was to enclose the tower. The foundations of the chapel, designed by the architect Dimitrije T. Leko, were consecrated in 1894.[15] A plaque dedicated near the chapel in 1904 reads: "To the first Serbian liberators after Kosovo."[14]

The chapel was renovated in 1937 and a bust of Sinđelić was added the following year. In 1948, Skull Tower and the chapel were declared Cultural Monuments of Exceptional Importance and came under the protection of the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Further renovation of the chapel occurred again in 1989.[16] As of 2024, 58 skulls remain embedded in the tower walls.[17] The one said to belong to Sinđelić rests in a glass container adjacent to the structure.[14]

Legacy

Skull Tower remains one of the most prominent symbols of Ottoman rule in Serbia.[18] It "continues to serve as an important heritage site for Serbian national identity," the political scientist Bilgesu Sümer writes.[10] In Serbia, and among Serbs both inside and outside the country, it is considered a symbol of the country's struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire.[19] In the centuries following its construction, it has become a place of Serb pilgrimage.[14] Prior to the breakup of Yugoslavia, tens of thousands of schoolchildren from across Yugoslavia visited the structure.[14] Skull Tower remains one of the most visited destinations in Serbia, attracting between 30,000 and 50,000 visitors annually.[16]

The Serbian poet Milan Đorđević considers Skull Tower to be emblematic of what he terms "Balkan horror".[20] Drawing on themes from Serbian history, in 1957, composer Dušan Radić composed the cantata Ćele kula.[21] Skull Tower is also the subject of the eponymous fourth cycle of modernist Vasko Popa's fourth collection of poems, Uspravna zemlja (Earth Erect), which was completed in 1971.[22] The structure was featured on the cover of the Serbian rock band Riblja Čorba's 1985 album Istina, with the band members' faces embedded in the tower walls. The cover was designed by the artist Jugoslav Vlahović.[23] An exhibition at the Military Museum in Belgrade contains a replica of the tower.[8]

Gallery

- Skull Tower

South side

South side North side

North side East side

East side Detail of a row of skulls

Detail of a row of skulls Skull that is said to have belonged to Stevan Sinđelić

Skull that is said to have belonged to Stevan Sinđelić

Notes

- ↑ "Информациони систем непокретних културних добара".

- ↑ Judah 2000, p. 51.

- 1 2 Damnjanović & Merenik 2004, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Castellan 1992, p. 241.

- 1 2 Vucinich 1982, p. 141.

- ↑ Hall 1995, p. 297.

- 1 2 3 4 Judah 2000, p. 279.

- 1 2 Merrill 2001, p. 178.

- ↑ Quigley 2001, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 Sümer 2021, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Jezernik 2004, p. 144.

- ↑ Hürriyet Daily News 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Longinović 2011, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Judah 2000, p. 280.

- 1 2 Makuljević 2012, pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 Babović 14 July 2009.

- ↑ Pavićević 2021, p. 148.

- ↑ Garcevic 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Levy 2015, p. 222.

- ↑ Merrill 2001, p. 179.

- ↑ Milin 2009, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Lekić 1993, p. 38.

- ↑ Kostić 28 December 2015.

References

- Books

- Castellan, Georges (1992). History of the Balkans: From Mohammed the Conqueror to Stalin. Boulder, Colorado: East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-222-4.

- Damnjanović, Nebojša; Merenik, Vladimir (2004). The First Serbian Uprising and the Restoration of the Serbian State. Belgrade, Serbia: Historical Museum of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-7025-371-1.

- Hall, Brian (1995). Impossible Country: A Journey Through the Last Days of Yugoslavia. New York City: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-024923-1.

- Jezernik, Božidar (2004). Wild Europe: The Balkans in the Gaze of Western Travellers. London, England: Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-574-8.

- Judah, Tim (2000). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.

- Lekić, Anita (1993). The Quest for Roots: The Poetry of Vasko Popa. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-820417-77-6.

- Levy, Michele Frucht (2015). "From Skull Tower to Mall: Competing Victim Narratives and the Politics of Memory in the Former Yugoslavia". In Mitroiu, Simona (ed.). Life Writing and Politics of Memory in Eastern Europe. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 202–221. ISBN 978-1-137-48552-6.

- Longinović, Tomislav (2011). Vampire Nation: Violence as Cultural Imaginary. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5039-2.

- Makuljević, Nenad (2012). "Public Monuments, Memorial Churches and the Creation of Serbian National Identity in the 19th Century". In Zimmermann, Tanja (ed.). Balkan Memories: Media Constructions of National and Transnational History. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript Verlag. pp. 33–40. ISBN 978-3-8394-1712-6.

- Merrill, Christopher (2001). Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-74251-686-1.

- Milin, Melita (2009). "Serbian Music of the Second Half of the 20th Century: From Socialist Realism to Postmodernism". In Romanou, Katy (ed.). Serbian and Greek Art Music: A Patch to Western Music History. Bristol, England: Intellect Books. pp. 81–96. ISBN 978-1-84150-338-7.

- Pavićević, Aleksandra (2021). Funerary Practices in Serbia. Bingley, West Yorkshire: Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78769-179-7.

- Sümer, Bilgesu (2021). "The Invisible Dimension of Institutional Violence and the Political Construction of Impunity: Necropopulism and the Averted Medicolegal Gaze". In Ribas-Mateos, Natalia; Dunn, Timothy J. (eds.). Handbook on Human Security, Borders and Migration. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 137–147. ISBN 978-1-83910-890-7.

- Quigley, Christine (2001). Skulls and Skeletons: Human Bone Collections and Accumulations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1068-2.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. (1982). "The Serbian Insurgents and the Russo-Turkish War of 1809–1812". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). First Serbian Uprising, 1804–1813. New York City: Columbia University Press. pp. 141–174. ISBN 978-0-930888-15-2.

- Websites

- Babović, S. (14 July 2009). "Ćele-kula za svetsku baštinu". Večernje novosti (in Serbian). Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- Garcevic, Srdjan (19 December 2016). "Finding a Serbian Thread in the Silk Road". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- Kostić, Petar (28 December 2015). "Himna slobode: 30 godina Istine i "Anđela"". BalkanRock (in Serbian). Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- "Ottoman tower tops list of buildings made with bones". Hürriyet Daily News. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

External links

- Battle of Čegar, official website of the municipality of Niš (in English)

- Ćele-kula National Museum Niš (in Serbian)