A crystal ball is a crystal or glass ball commonly used in fortune-telling. It is generally associated with the performance of clairvoyance and scrying in particular. Other names include crystal sphere, gazing ball, shew stone, and show stone. In neopaganism it is sometimes called an orbuculum.

History

By the fifth century CE, scrying using crystal balls was widespread within the Roman Empire and was condemned by the early medieval Christian Church as heretical.[1]

The tomb of Childeric I, a fifth-century king of the Franks, contained a 3.8 cm diameter transparent beryl globe.[2] The object is similar to other globes that were later found in tombs from the Merovingian period in France and the Saxon period in England. Some of these were complete with a frame suggesting an ornamental object.[3] It has been pointed out that these mounts are identical to those of later globes also believed to be used for magic or divination, indicating that these crystal globes may have been used for crystallomancy.[4][5]

John Dee was a noted British mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I. He devoted much of his life to alchemy, divination, and Hermetic philosophy, of which the use of crystal balls was often included.[6]

Crystal gazing was a popular pastime in the Victorian era, and was claimed to work best when the Sun is at its northernmost declination. Immediately before the appearance of a vision, the ball was said to mist up from within.[1]

The use of crystal balls for divination also has a long history with the Romani people.[7] Fortune tellers, known as drabardi,[8] traditionally use crystal balls as well as cards to seek knowledge about future events.[9]

Art of scrying

The process of scrying often involves the use of crystals, especially crystal balls, in an attempt to predict the future or otherwise divine hidden information.[10] Crystal ball scrying is commonly used to seek supernatural guidance while making difficult decisions in one's life (e.g., matters of love or finances).[11][12]

When the technique of scrying is used with crystals, or any transparent body, it is known as crystallomancy or crystal gazing.

In stage magic

Crystal balls are popular props used in mentalism acts by stage magicians. Such routines, in which the performer answers audience questions by means of various ruses, are known as crystal gazing acts. One of the most famous performers of the 20th century, Claude Alexander, was often billed as "Alexander the Crystal Seer".[13]

Optics

Optically, a crystal ball is a ball lens. For typical materials such as quartz and glass, it forms an image of distant objects slightly beyond the surface of the sphere, on the opposite side. Unlike conventional lenses, the image-forming properties are omnidirectional (independent of the direction being imaged)

This omnidirectional focusing can cause a crystal ball to act as a burning glass when it is brought into full sunlight. The image of the sun formed by a large crystal ball will burn a hand that is holding it, and can ignite dark-coloured flammable material placed near it.[14]

Famous crystal balls

A crystal ball was among the grave-goods of the Merovingian King, Childeric I (c. 437–481 AD).[15] The grave-goods were discovered in 1653. In 1831, they were stolen from the royal library in France where they were being kept. Few items were ever recovered. The crystal ball was not among them.

The Sceptre of Scotland has a crystal ball in its finial, honoring the tradition of their use by pagan druids.[16] It was made in Italy in the 15th century, and was a gift to James IV from Pope Alexander VI.

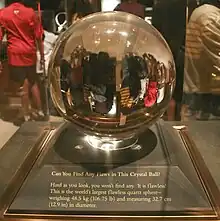

The Penn Museum in Philadelphia displays the third-largest crystal ball as the central object in its Chinese Rotunda.[17] Weighing 49 pounds (22 kg), the sphere is made of quartz crystal from Burma and was shaped through years of constant rotation in a semi-cylindrical container filled with emery, garnet powder, and water. The ornamental treasure was purportedly made for the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) during the Qing dynasty in the 19th century, but no evidence as to its actual origins exists. The crystal ball and an ancient Egyptian statuette[18] which depicted the god Osiris were stolen in 1988.[19] They were recovered three years later with no damage done to either object.

See also

- Crystal skull

- Gazing ball

- Magic Mirror (Snow White)

- Palantír

- Salvator Mundi (Leonardo), da Vinci's "Savior of the World" painting depicting Christ holding a crystal ball

- Seer stone (Latter Day Saints)

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Crystal gazing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Besterman, 1995, pg. 45

- ↑ Besterman, 1995, pg. 46

- ↑ Besterman, 1995, pg. 46

- ↑ George Frederick Kunz (1913). The Curious Lore of Precious Stones. Philadelphia: Lippincott. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-486-22227-1.

- ↑ "John Dee's crystal ball". TT Research Projects. Archived from the original on 2023-03-15. Retrieved 2023-06-06 – via ensemble.va.com.au.

- ↑ "Where did crystal balls come from?". History Daily (historydaily.org). May 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Fortune telling as part of the Roma Culture". rozvitok.org. Правозахисний фонд "Розвиток" [Human Rights Fund "Development"]. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ↑ "ЦЫГАНЕ И ЦЫГАНСКИЕ ГАДАНИЯ" [Gypsies and gypsy fortune-telling]. sekukin.narod.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ↑ "scry". dictionary.com (definition). Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ↑ Chauran, Alexandra (2011). Crystal Ball Reading for Beginners: A down to Earth guide. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

- ↑ "Lensball photography". lensball.com.au. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ↑ Copperfield, David; Wiseman, Richard; Britland, David (2021). David Copperfield's History of Magic. Liwag, Homer (photographer) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-9821-1291-2. OCLC 1236259508.

- ↑ "Crystal ball starts fire at Okla. home". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 29 January 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Chifflet, J.-J. (1665). Anastasis Childerici I. Francorum Regis, site Thesaurus sepulchralis Tornaci Neruiorum effossus, & commentario illustratus [Raising up of Childeric I, King of the Franks, [his grave-]site excavated sepulchral treasure of Tournai [in Belgium], & illustrated commentary] (in Latin).

- ↑ Ferguson, Sibyl (30 June 2005). Crystal Ball: Stones, amulets, and talismans for power, protection, and prophecy. Weiser Books. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-57863-348-7 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Crystal sphere". University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania. 335728. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ↑ "Statue". University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania. 276512. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ↑ "Penn Museum crystal ball, statue stolen; guard ignored burglar alarms". Philly.com. 12 November 1988. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

Further reading

- Lang, Andrew (1900). "Chapter V Crystal visions, savage and civilised". The Making of Religion. London, UK / New York, NY / Bombay, IN: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 83–104.

- Ferguson, Sibyl (1980). The Crystal Ball. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-483-0.

- Besterman, Theodore (1995). Crystal Gazing: A Study in the History, Distribution, Theory and Practice of Scrying. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-56459-542-0.

- George Frederick Kunz (1913). "Chapter VI Crystal balls and Crystal Gazing". The Curious Lore of Precious Stones. Philadelphia: Lippincott. pp. 176–225. ISBN 0-48622-227-6.

External links

Media related to crystal balls at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to crystal balls at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of crystal ball at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of crystal ball at Wiktionary