'Anata | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | عناتا |

| • Latin | Anata (official) |

%252C_p._549_in_Thomson%252C_1859.jpg.webp) 'Anata, around 1859[2] | |

'Anata Location of 'Anata within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°48′46″N 35°15′43″E / 31.81278°N 35.26194°E | |

| Palestine grid | 174/135 |

| State | |

| Governorate | Jerusalem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village council |

| • Head of Municipality | Ahmad Kamil Alrifai |

| Area | |

| • Total | 30,603 dunams (30.6 km2 or 11.8 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[3] | |

| • Total | 16,919 |

| • Density | 550/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Anata, personal name[4] |

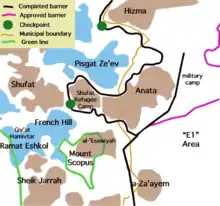

'Anata (Arabic: عناتا) is a Palestinian town in the Jerusalem Governorate of the State of Palestine, in the central West Bank, located four kilometers northeast of Jerusalem's Old City. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 'Anata had a population of 16,919 in 2017.[3] Its total land area is 30,603 dunams, of which over half now lies within the Israeli Jerusalem municipality and 1,654 is Palestinian built-up area.[5] Since 1967, 'Anata has been occupied by Israel. Together with Shu'afat refugee camp, the village is almost surrounded by the separation barrier, cutting it off from Jerusalem and surrounding villages except for a checkpoint in the west and a road in the north-east that gives access to the rest of the West Bank.[6]

History

'Anata is a village on an ancient site, old stones have been reused in village homes, and cisterns dug into rock have been found, together with caves and ancient agricultural terraces.[7] The prophet Jeremiah was born there from the priest family of ‘Anata.

Bronze and Iron Ages

Edward Robinson identified 'Anata with the biblical town of Anathoth, birthplace of Jeremiah, in his Biblical Researches in Palestine.[8] This identification is accepted by Finkelstein. Findings from 'Anata include pottery from the Iron Age II and the Hellenistic period.[9]

The toponym may be linked to the Canaanite goddess Anat.[10]

Byzantine period

There are ruins of a Byzantine-era church in the town, proving that it was inhabited prior to the Muslim conquest of Palestine by the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century.[11][12]

Ayyubid period

Ahead of the 1187 Muslim siege of Jerusalem against the Crusaders, Saladin, the Ayyubid general and sultan, situated his administration in 'Anata before he proceeded towards Jerusalem.[5]

Ottoman period

The village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1516 with all of Palestine, and in 1596 'Anata appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Quds of the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 10 Muslim households. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 40 % on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, summer crops, olive trees, fruit trees, goats and/or bee hives; a total of 9,300 Akçe. All of the revenue went to a Waqf.[13]

The village was destroyed by Ibrahim Pasha in 1834 following a pro-Ottoman Arab revolt against Egyptian rule.[5] In 1838 Anata was noted as a Muslim village, located north of Jerusalem.[14][8]

When W. M. Thomson visited it in the 1850s, he described it as a "small, half-ruined hamlet, but it was once much larger, and appears to have had a wall around it, a few fragments of which are still to be seen."[15]

In 1863 Victor Guérin visited the village and described it as being a small, situated on a hill, and with 200 inhabitants.[16] Socin found from an official Ottoman village list from about 1870 that 'Anata had 25 houses and a population of 70, though the population count included men, only.[17][18] According to information received by Clermont-Ganneau in 1874, the village was settled by Arab families from Khirbet 'Almit, a mile to the northeast.[11][19]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described it as a "village of moderate size, the houses of stone; it stands on a ridge commanding a fine view to the north and east. ...There are a few olives round the village, and a well on the west and another on the south-east."[20]

In 1896 the population of 'Anata was estimated to be about 180 persons.[21]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, 'Anata had a population of 285, all Muslim,[22] increasing in the 1931 census to 438, still all Muslim, in 98 houses.[23]

In the 1945 statistics 'Anata had a population of 540 Muslims,[24] with 18,496 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey.[25] Of this, 353 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 2,645 used for cereals,[26] while 35 dunams were built-up land.[27]

Jordanian period (1948-1967)

In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, 'Anata came under Jordanian rule.

The Jordanian census of 1961 found 852 inhabitants in 'Anata.[28]

Israeli and PA period (1967-current)

After the Six-Day War in 1967, 'Anata has been under Israeli occupation.[29] The population in the 1967 census conducted by the Israeli authorities was 1,260, 121 of whom originated from the Israeli territory.[30] At the time of the conquest Anata was one of the most expansive towns in the West Bank, extending from Jerusalem to the wadis near Jericho. Most of its land was confiscated to create the Israeli military base at Anatot, 4 Israeli settlements and several illegal Israeli outposts.[10]

After the 1995 accords, about 3.8% of the land (or 918 dunams) is classified as being Area B, while the remaining 96.2 % (or 23,108 dunams) is Area C.[31] Most of the lands of 'Anata have been confiscated by Israel.[29] Of the 1877 dunums which remain in residents' hands, after creation of the Palestinian National Authority in 1994, 957 dunums became part of Area B, 220 dunums part of Area C, and 700 dunums have been declared a closed military zone by the Israeli authorities.[29] The Dahyat as-Salam neighbourhood has been annexed by Israel as part of the Jerusalem municipality.[29] The village boundaries are far-reaching and stretch from 'Anata itself to just east of the Israeli settlement of Alon.[32] Most of the land is undeveloped open space with little or no vegetation.[32]

According to ARIJ, Israel has confiscated land from 'Anata for the construction of 4 Israeli settlements:

- 328 dunams for Alon,[33]

- 717 dunams for Nofei Prat,[33]

- 820 dunams for Kfar Adumim,[33]

- 783 dunams for Almon.[33]

Ayn Fara, the Palestinian village’s natural pool and spring, was absorbed into the Israeli Ein Prat Nature Reserve.[10]

Main families

The families are Shiha, Abd al-Latif, Ibrahim, Alayan, Hilwa, Salama, Hamdan, Abu Haniya Musah and al-Kiswani. The latter family fled to 'Anata during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[5]

Sanctuaries

Saleh and Rumia

'Anata contains two sanctuaries, dedicated to Saleh and possibly Jeremiah. The former is a mosque dedicated to the prophet Saleh (Biblical Shelah), but Saleh's tomb is believed to be in the village of Nabi Salih to the northwest. The latter sanctuary is a cave dedicated to a "Rumia" which according to Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, "looks as if it had been connected by the folklore with the name Jeremiah, the initial 'je' being removed by aphaeresis as so frequently happens in Arabic." This signifies that it is very possible that "Rumia" is an Arabicized form of "Jeremiah".[11][19]

'Abd es-Sallam

Northeast of 'Anata lies a shrine dedicated to Seikh 'Abd es-Sallam a-Rifa'i, locally known as Abu 'Anata. He is believed to be the same as the saint named es-Sallam ibn a-Sid el-Amir Muhammad Qaraja e-Rifa'i, who served as the governor of Syria. According to one tradition, he arrived in Palestine from Morocco and acquired lands in 'Anata, subsequently becoming the village's founding father, with all its residents considered his descendants. Another account suggests that 'Abd es-Sallam a-Rifa'i was a renowned Islamic scholar who studied at Al-Azhar. Upon arriving at the governor's palace in Syria, he requested a piece of land in Jerusalem where he could live and eventually die. The governor granted him 'Anata and its surroundings, totaling 33 thousand acres. 'Abd es-Sallam engaged in religious studies there and at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and from that time onward, his descendants multiplied in this village.[34]

Several legends have become linked to the tomb. In one tale, it is recounted that a descendant of the seikh engaged in a conflict with an individual from Hizma who, in a fit of anger, cursed both the man and the sheikh. Seeking resolution, the cursed man went to the sheikh's tomb and implored for intervention. Remarkably, the saint appeared that very night before the man from Hizma, rendering him paralyzed and ultimately leading to his death a few days later. Additionally, the site historically served as a venue for elaborate circumcision ceremonies. Reconstructed in the early 20th century, it continues to be a visited site by locals to this day.[34]

Local administration

Before 1996, 'Anata was governed by a mukhtar. Since then a village council was established to govern the town.[5]

References

- Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 549

- ↑ Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 549

- 1 2 Preliminary Results of the Population, Housing and Establishments Census, 2017 (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) (Report). State of Palestine. February 2018. pp. 64–82. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 283

- 1 2 3 4 5 'Anata Town Profile Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem. 21 July 2004.

- ↑ Btselem (Nov 2014) Map of the West Bank, Settlements and the Separation Barrier

- ↑ Dauphin, 1998, p. 899

- 1 2 Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 109

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel (2018). Hasmonean realities behind Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles. SBL Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-88414-307-9. OCLC 1081371337.

- 1 2 3 Nathan Thrall, 'A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: One man’s quest to find his son lays bare the reality of Palestinian life under Israeli rule,' New York Review of Books 19 March 2021:'the town of Anata was once among the most expansive in the West Bank, stretching eastward from the tree-lined mountains of Jerusalem down to the pale yellow hills, rocky canyons, and desert wadis at the edge of the district of Jericho, in the Jordan Valley. Today, Anata is much smaller, the bulk of its lands confiscated to create the Israeli military base of Anatot, four official settlements, and several unauthorized settler outposts.'

- 1 2 3 Sharon, 1999, p. 87

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 82

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 117

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 122

- ↑ Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 548

- ↑ Guérin, 1869, p. 76 ff

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 143

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 127 noted 52 houses

- 1 2 Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, vol 2, pp. 276-7

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, pp. 7-8

- ↑ Schick, 1896, p. 121

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ↑ Mills,1932, p. 37

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 56

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 101

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 151

- ↑ Government of Jordan, 1964, p. 23

- 1 2 3 4 "Anata". Grassroots Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ↑ Perlmann, Joel (November 2011 – February 2012). "The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ 'Anata Town Profile, ARIJ, p. 18

- 1 2 Land Use/Land Cover Map of 'Anata Village Boundary (Map). Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 2005-12-22. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- 1 2 3 4 'Anata Town Profile, ARIJ, p. 19

- 1 2 Tal, Uri (2023). Muslim Shrines. Yad Ben-Zvi. pp. 238–9. ISBN 978-965-217-452-9.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Sharon, M. (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Vol. I, A. BRILL. ISBN 9004108335.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

External links

- Welcome To 'Anata

- Anata

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- 'Anata Town (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- 'Anata Town Profile, ARIJ

- 'Anata aerial photo, ARIJ

- Locality Development Priorities and Needs in 'Anata, ARIJ