Agra | |

| UTC time | 1935-05-30 21:32:57 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 904311 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 31 May 1935 |

| Local time | Between 2:33 and 3:40 (PKT) |

| Magnitude | 7.7 Mw |

| Depth | 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) |

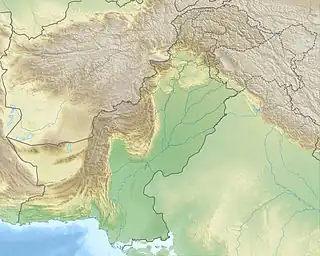

| Epicenter | 29°30′N 66°48′E / 29.5°N 66.8°E[1] |

| Areas affected | Balochistan, British India (now Pakistan) |

| Max. intensity | X (Extreme)[1] |

| Casualties | 30,000–60,000[2] |

An earthquake occurred on 31 May 1935 between 2:30 am and 3:40 am at Quetta, Balochistan, British India (now part of Pakistan), close to the border with southern Afghanistan. The earthquake had a magnitude of 7.7 Mw [3] and anywhere between 30,000 and 60,000 people died from the impact.[2] It was recorded as the deadliest earthquake to strike South Asia until 2005.[3] The quake was centred 4 km south-west of Ali Jaan, Balochistan, British India.[3]

Quetta and its neighbouring towns lie in the most active seismic region of Pakistan atop the Chaman and Chiltan faults. Movement on the Chaman Fault[4] resulted in an earthquake early in the morning on 31 May 1935 estimated anywhere between the hours of 2:33 am[3] and 3:40 am[5] which lasted for three minutes with continuous aftershocks. Although there were no instruments good enough to precisely measure the magnitude of the earthquake, modern estimates cite the magnitude as being a minimum of 7.7 Mw and previous estimates of 8.1 Mw are now regarded as an overestimate. The epicentre of the quake was established to be 4-kilometres south-west of the town of Ali Jaan in Balochistan, some 153-kilometres away from Quetta in British India. The earthquake caused destruction in almost all the towns close to Quetta, including the city itself, and tremors were felt as far as Agra, now in India. The largest aftershock was later measured at 5.8 Mw occurring on 2 June 1935.[3] The aftershock, however, did not cause any damage in Quetta, but the towns of Mastung, Maguchar and Kalat were seriously affected.[3]

Aftermath

Casualties

Most of the reported casualties occurred in the city of Quetta. Initial communiqué drafts issued by the government estimated a total of 25,000 people buried under the rubble, 10,000 survivors and 4,000 injured. The city was badly damaged and was immediately prepared to be sealed under military guard with medical advice.[5] All the villages between Quetta and Kalat were destroyed, and the British feared casualties would be higher in surrounding towns; it was later estimated to be nowhere close to the damage caused in Quetta.

Infrastructure was severely damaged. The railway area was destroyed and all the houses were razed to the ground with the exception of the Government House that stood in ruins. A quarter of the Cantonment area was destroyed, with military equipment and the Royal Air Force garrison suffering serious damage. It was reported that only 6 out of the 27 machines worked after the initial seismic activity.[5] A Regimental Journal for the 1st Battalion of the Queen's Royal Regiment based in Quetta issued in November 1935 stated,

It is not possible to describe the state of the city when the battalion first saw it. It was razed to the ground. Corpses were lying everywhere in the hot sun and every available vehicle in Quetta was being used for the transportation of injured … Companies were given areas in which to clear the dead and injured. Battalion Headquarters were established at the Residency. Hardly had we commenced our work than we were called upon to supply a party of fifty men, which were later increased to a hundred, to dig graves in the cemetery.[5]

Rescue efforts

Tremendous losses were incurred on the city in the days following the event, with many people buried beneath the debris still alive. British Army regiments were among those assisting in rescue efforts,[5] with Lance-Sergeant Alfred Lungley of the 24th Mountain Brigade earning the Empire Gallantry Medal for highest gallantry.[6] In total, eight Albert Medals, nine Empire Gallantry Medals and five British Empire Medals for Meritorious Service were awarded for the rescue effort, most to British and Indian soldiers.[7]

The weather did not help, and the scorching summer heat made matters worse. Bodies of European and Anglo-Indians were recovered and buried in a British cemetery where soldiers had dug trenches. Padres performed the burial service in haste, with soldiers quickly covering the graves.[5] Others were removed in the same way and taken to a nearby shamshāngāht for their remains to be cremated.

While the soldiers excavated through the debris for a sign of life, the Government sent the Quetta administration instructions to build a tent city to house the homeless survivors and to provide shelter for their rescuers. A fresh supply of medicated pads was brought for the soldiers to wear over their mouths while they dug for bodies in fears of a spread of disease from the dead bodies buried underneath.[5]

|

Significance

The natural disaster ranks as the 23rd most deadly earthquake worldwide to date. In the aftermath of the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, the Director General for the Meteorological Department at Islamabad, Chaudhry Qamaruzaman, cited the earthquake as being amongst the four deadliest earthquakes the South Asian region has seen; the others being the Kashmir earthquake in 2005, 1945 Balochistan earthquake and Kangra earthquake in 1905.

Notable survivors

Indian space scientist and educationist Yash Pal, then eight-years-old, was trapped under the building remains, together with his siblings, and was rescued.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Significant earthquake". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- 1 2 M.Y.H. Bangash (2011). Earthquake Resistant Buildings: Dynamic Analyses, Numerical Computations, Codified Methods, Case Studies and Examples. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-540-93818-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The great Quetta tragedy". Pakistan: Dawn. 25 October 2005.

- ↑ Pararas-Carayannis, G. "The Earthquake of May 30, 1935, in Quetta, Balochistan". Disaster Pages. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "1st Queen's at Quetta – The Earthquake". Queens Royal Surreys. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ↑ "Lungley on www.essex-family-history.co.uk". Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- ↑ "No. 34221". The London Gazette. 19 November 1935. p. 7317.

- ↑ JAYAN, T. V. (2 August 2017). "For the love of science". Frontline.

Further reading

- Government of India Staff. The Quetta Earthquake 1935. Pagoda Tree Press. ISBN 978-1-904289-34-0.

- Haines, Daniel (May 2019). "Historical Case Study: India 1935: Earthquake" (PDF). Shelter Projects 2017–2018. Global Shelter Cluster. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

External links

- 1935 Quette Earthquake – Dawn

- 1st Queen's at Quetta – The Earthquake

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.