A Sea Symphony is an hour-long work for soprano, baritone, chorus and large orchestra written by Ralph Vaughan Williams between 1903 and 1909. The first and longest of his nine symphonies, it was first performed at the Leeds Festival in 1910 with the composer conducting, and its maturity belies the relatively young age — 30 — when he began sketching it. Moreover it is one of the first symphonies in which a chorus is used throughout as an integral part of the texture and it helped set the stage for a new era of symphonic and choral music in Britain during the first half of the 20th century. It was never numbered.

History

From 1903 to 1909, Ralph Vaughan Williams worked intermittently on a series of songs for chorus and orchestra that were to become his most lengthy project to date and his first true symphony. Originally titled The Ocean, A Sea Symphony was first performed in 1910 at the Leeds Festival on the composer's 38th birthday. This is generally cited as his first large-scale work; although Grove lists some 16 other orchestral works composed by Vaughan Williams before he completed A Sea Symphony, including two with chorus, the vast majority of those are juvenilia or apprentice works that have never been published and are long since withdrawn from circulation. Nevertheless, Vaughan Williams had never before attempted a work of quite this duration, or for such large forces, and it was his first of what would eventually be nine symphonies. Like Brahms, Vaughan Williams delayed a long time before composing his first symphony, but remained prolific throughout the end of his life: his final symphony was composed from 1956 to 1958, and completed when he was 85 years of age.

Structure

At approximately 70 minutes, A Sea Symphony is the longest of all Vaughan Williams's symphonies. Although it represents a departure from the traditional Germanic symphonic tradition of the time, it follows a fairly standard symphonic outline: fast introductory movement, slow movement, scherzo, and finale. The four movements are:

- A Song for All Seas, All Ships (baritone, soprano, and chorus)

- On the Beach at Night, Alone (baritone and chorus)

- Scherzo: The Waves (chorus)

- The Explorers (baritone, soprano, semi-chorus, and chorus)

The first movement lasts roughly twenty minutes; the inner movements approximately eleven and eight minutes, and the finale lasts roughly thirty minutes.

Text

The text of A Sea Symphony comes from Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Though Whitman's poems were little known in England at the time, Vaughan Williams was introduced to them by Bertrand Russell, a family friend. Vaughan Williams was attracted to them for their ability to transcend both metaphysical and humanist perspectives. Whitman's use of free verse was also beginning to make waves in the compositional world, where fluidity of structure was beginning to be more attractive than traditional, metrical settings of text. Vaughan Williams sets sections from the following poems in A Sea Symphony:

Behold, the sea itself,

And on its limitless, heaving breast, the ships;

See, where their white sails, bellying in the wind, speckle the green and blue,

See, the steamers coming and going, steaming in or out of port,

See, dusky and undulating, the long pennants of smoke.

1 To-day a rude brief recitative,

Of ships sailing the seas, each with its special flag or ship-signal,

Of unnamed heroes in the ships—of waves spreading and spreading far as the eye can reach,

Of dashing spray, and the winds piping and blowing,

And out of these a chant for the sailors of all nations,

Fitful, like a surge.

Of sea-captains young or old, and the mates, and of all intrepid sailors,

Of the few, very choice, taciturn, whom fate can never surprise nor death dismay.

Pick'd sparingly without noise by thee old ocean, chosen by thee,

Thou sea that pickest and cullest the race in time, and unitest nations,

Suckled by thee, old husky nurse, embodying thee,

Indomitable, untamed as thee. ...

2 Flaunt out O sea your separate flags of nations!

Flaunt out visible as ever the various ship-signals!

But do you reserve especially for yourself and for the soul of man one flag above all the rest,

A spiritual woven signal for all nations, emblem of man elate above death,

Token of all brave captains and all intrepid sailors and mates,

And all that went down doing their duty,

Reminiscent of them, twined from all intrepid captains young or old,

A pennant universal, subtly waving all time, o'er all brave sailors,

One flag, one flag above all the rest.

Behold, the sea itself,

And on its limitless heaving breast, the ships

All seas, all ships.

- Movement 2: "On the Beach at Night Alone"

On the beach at night alone,

As the old mother sways her to and fro singing her husky song,

As I watch the bright stars shining, I think a thought of the clef of the universes and of the future.

A vast similitude interlocks all, ...

All distances of place however wide,

All distances of time, ...

All souls, all living bodies though they be ever so different, ...

All nations, ...

All identities that have existed or may exist ...,

All lives and deaths, all of the past, present, future,

This vast similitude spans them, and always has spann'd,

And shall forever span them and compactly hold and enclose them.

- Movement 3: "After the Sea-ship", (taken in its entirety):

After the sea-ship, after the whistling winds,

After the white-gray sails taut to their spars and ropes,

Below, a myriad myriad waves hastening, lifting up their necks,

Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship,

Waves of the ocean bubbling and gurgling, blithely prying,

Waves, undulating waves, liquid, uneven, emulous waves,

Toward that whirling current, laughing and buoyant, with curves,

Where the great vessel sailing and tacking displaced the surface,

Larger and smaller waves in the spread of the ocean yearnfully flowing,

The wake of the sea-ship after she passes, flashing and frolicsome under the sun,

A motley procession with many a fleck of foam and many fragments,

Following the stately and rapid ship, in the wake following.

- Movement 4: "Passage to India"

5 O vast Rondure, swimming in space,

Cover'd all over with visible power and beauty,

Alternate light and day and the teeming spiritual darkness,

Unspeakable high processions of sun and moon and countless stars above,

Below, the manifold grass and waters, animals, mountains, trees,

With inscrutable purpose, some hidden prophetic intention,

Now first it seems my thought begins to span thee.

Down from the gardens of Asia descending ...,

Adam and Eve appear, then their myriad progeny after them,

Wandering, yearning, ..., with restless explorations,

With questionings, baffled, formless, feverish, with never-happy hearts,

With that sad incessant refrain, Wherefore unsatisfied soul? ...

Whither O mocking life?

Ah who shall soothe these feverish children?

Who Justify these restless explorations?

Who speak the secret of impassive earth? ...

Yet soul be sure the first intent remains, and shall be carried out,

Perhaps even now the time has arrived.

After the seas are all crossed, (...)

After the great captains and engineers have accomplished their work,

After the noble inventors, ...

Finally shall come the poet worthy that name,

The true son of God shall come singing his songs.

8 O we can wait no longer,

We too take ship O soul,

Joyous we too launch out on trackless seas,

Fearless for unknown shores on waves of ecstasy to sail,

Amid the wafting winds, (thou pressing me to thee, I thee to me, O soul,)

Caroling free, singing our song of God,

Chanting our chant of pleasant exploration.

O soul thou pleasest me, I thee,

Sailing these seas or on the hills, or waking in the night,

Thoughts, silent thoughts, of Time and Space and Death, like waters flowing,

Bear me indeed as through the regions infinite,

Whose air I breathe, whose ripples hear, lave me all over,

Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee,

I and my soul to range in range of thee.

O Thou transcendent,

Nameless, the fibre and the breath,

Light of the light, shedding forth universes, thou centre of them, ...

Swiftly I shrivel at the thought of God,

At Nature and its wonders, Time and Space and Death,

But that I, turning, call to thee O soul, thou actual Me,

And lo, thou gently masterest the orbs,

Thou matest Time, smilest content at Death,

And fillest, swellest full the vastnesses of Space.

Greater than stars or suns,

Bounding O soul thou journeyest forth; ...

9 Away O soul! hoist instantly the anchor!

Cut the hawsers—haul out—shake out every sail! ...

Sail forth—steer for the deep waters only,

Reckless O soul, exploring, I with thee, and thou with me,

For we are bound where mariner has not yet dared to go, ...

O my brave soul!

O farther farther sail!

O daring joy, but safe! are they not all the seas of God?

O farther, farther, farther sail!

Music

Orchestration

The symphony is scored for soprano, baritone, chorus and a large orchestra consisting of:

- Woodwinds: two flutes, piccolo, two oboes, cor anglais, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba

- Percussion: timpani (F♯2–F3), side drum, bass drum, triangle, suspended cymbal, crash cymbals

- Organ (1st and 4th movements)

- Strings: two harps, and strings.

To facilitate more performances of the work, the full score also includes the provision that it may be performed by a reduced orchestra of two flutes (second doubling piccolo), one oboe, cor anglais, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, one harp, and strings.

The chorus sings in all four movements. Both soloists are featured in the first and last movements, while only the baritone sings in the second movement. The scherzo is for the chorus and orchestra alone.

Influences

A Sea Symphony is among the best-known of a host of sea-related pieces being written around the same time in England, some of the most famous of which are Stanford's Songs of the Sea (1904) and Songs of the Fleet (1910), Elgar's Sea Pictures (1899), and Frank Bridge's The Sea (1911). Debussy's La mer (1905) may also have been influential in this apparent nautical obsession.

Comparisons to Stanford, Parry, and Elgar, as in the Grove article, are expected. Not only were the four writing during the same era and in the same country, Vaughan Williams studied with both Stanford and Parry at the Royal College of Music (RCM), and his preparations for composing A Sea Symphony included study of both Elgar's Enigma Variations (1898–99) and his oratorio The Dream of Gerontius (1900).

Vaughan Williams studied with Ravel for three months in Paris in the winter of 1907–1908. Though he worked chiefly on orchestration, this was to provide quite a contrast to the Germanic tradition handed down through Stanford and Parry at the RCM, and perhaps began to give Vaughan Williams a greater sense for colour and a freedom to move chords as block units. His partiality towards mediant relationships, a unifying harmonic motive of A Sea Symphony, may have been somewhat liberated by these studies, and this harmonic relationship is now considered characteristic of his style in general. A Sea Symphony also makes use of both pentatonic and whole tone scales, now often considered idiomatic features of French music of the period. Almost certainly, this music was in Vaughan Williams's mind as he finished work on A Sea Symphony in 1908–1909, but Ravel paid him the great compliment of calling him “the only one of my students who does not write my music.”

Motives

Musically, A Sea Symphony contains two strong unifying motives. The first is the harmonic motive of two chords (usually one major and one minor) whose roots are a third apart. This is the first thing that occurs in the symphony; the brass fanfare is a B flat minor chord, followed by the choir singing the same chord, singing Behold, the sea. The full orchestra then comes in on the word sea, which has resolved into D major.

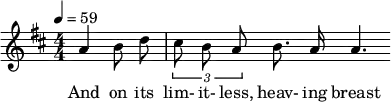

The second motive is a melodic figure juxtaposing duplets and triplets, set at the opening of the symphony (and throughout the first movement) to the words And, on its limitless heaving breast... In the common method of counting musical rhythms, the pattern could be spoken as 'one two-and three-two-three four', showing that the second beat is divided into eighth notes (for on its) and the third beat is divided into triplets (for limitless).

Reception and legacy

The impact of A Sea Symphony manifests itself not only in the life of the composer (his first symphony and first work of such an immense scale), but also in the newfound support and appreciation of the English symphony and 20th century English music in general. Hugh Ottaway's book, Vaughan Williams Symphonies presents the following observation in its introduction:

- “The English symphony is almost entirely a twentieth-century creation. When in 1903 Vaughan Williams began to sketch the songs for chorus and orchestra that became A Sea Symphony, Elgar had not yet emerged as a symphonist. And, extraordinary though it may seem, Elgar's First (1908) is the earliest symphony by an English composer in the permanent repertory. . . By the time Vaughan Williams had completed his Ninth [Symphony] – in 1958, a few months before his death at the age of 85 – the English symphony . . . had become a central figure of our musical revival. To say that Vaughan Williams played a major part in bringing this about is to state the obvious: throughout much of the period he was actively involved in English musical life, not only as a composer but as a teacher, conductor, organiser and, increasingly, advisor of young men.” (5)

In the Grove article on Vaughan Williams, Ottaway and Frogley call the work:

- “…a triumph of instinct over environment. The tone is optimistic, Whitman's emphasis on the unity of being and the brotherhood of man comes through strongly, and the vitality of the best things in it has proved enduring. Whatever the indebtedness to Parry and Stanford, and in the finale to Elgar, there is no mistaking the physical exhilaration or the visionary rapture.”

Ursula Vaughan Williams, in what has become the definitive biography of her husband Ralph Vaughan Williams, writes of his philosophy in a more general sense:

- “…he was aware of the common aspirations of generations of ordinary men and women with whom he felt a deep, contemplative sympathy. And so there is in his work a fundamental tension between traditional concepts of belief and morality and a modern spiritual anguish which is also visionary.”

References

- Day, James. Vaughan Williams, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. First published 1961.

- Dickinson, A. E. Vaughan Williams. London: Faber and Faber, 1963. Republished in facsimile by Scholarly Press, Inc. St. Clair Shores, MI.

- Foss, Hubert. Ralph Vaughan Williams. New York: Oxford University Press, 1950.

- Frogley, Alain, ed. Vaughan Williams Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Kennedy, Michael. The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams. London: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Ottaway, Hugh. Vaughan Williams Symphonies. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972.

- Ottaway, Hugh and Alain Frogley. “Vaughan Williams, Ralph.” Grove Music Online. ed. L. Macy, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic (subscription access)

- Schwartz, Elliot S. The Symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1964.

- Vaughan Williams, Ursula. R.V.W. A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams. London: Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass, (“Deathbed edition” 1891–92). London: J. M. Dent Ltd., 1993. First published 1855.

Further reading

- Clark, F. R. C. "The Structure of Vaughan Williams' 'Sea' Symphony". The Music Review 34, no. 1 (February 1973): 58–61.

- Heffer, Simon. Vaughan Williams. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000.

- Howes, Frank. The Music of Vaughan Williams. London: Oxford University Press, 1954.

- McGuire, Charles Edward. "Vaughan Williams and the English Music Festival, 1910." In Vaughan Williams Essays. Edited by Byron Adams and Robin Wells. Aldershot and Brookfield, VT: Ashgate Press, 2003. pp. 235–268.

- Mellers, Wilfrid. Vaughan Williams and the Vision of Albion. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1989. See esp. chap. 1, “The Parlour and the Open Sea: Conformity and Nonconformity in Toward the Unknown Region and A Sea Symphony.”

- Vaughan Williams, Ursula and Imogen Holst, eds. Heirs and Rebels: Letters written to each other and occasional writings on music by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Recordings

There are at least 20 recordings of the work:

- Sir Adrian Boult, conductor—Dame Isobel Baillie, soprano; John Cameron, baritone; with London Philharmonic Choir; London Philharmonic; Decca LXT 2907-08 (Kingsway Hall, Dec. 28-30, 1953 and Jan. 1, 1954)

- Sir Malcolm Sargent—Blighton (sop)/Cameron (bar)/choruses/BBC SO; Carlton BBC Radio Classics 15656 9150-2 (Sept. 22, 1965)

- Boult — Armstrong (sop)/Case (bar)/LP Choir/LPO, HMV SLS 780 (Kingsway Hall, Sept. 23–26, 1968)

- André Previn, conductor—Heather Harper, soprano; John Shirley-Quirk, baritone; with London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus; RCA Red Seal SER 5585 (Kingsway Hall, Feb. 9–16, 1970)

- Kazuyoshi Akiyama, conductor—Sakae Himoto, soprano; Koichi Tajiona, baritone; with Osaka Philharmonic and Chorus; Nippon Columbia OP 7103 (Festival Hall, Osaka, July 13, 1973)

- Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, conductor—Smoryakova, soprano; Vasiliev, baritone; with USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra; Leningrad Musical Society Choir and Rimsky-Korsakov Musical School Choir; Melodiya SUCD 10-00234 (Grand Hall of Leningrad Philharmony, April 30, 1988)

- Vernon Handley, conductor—Joan Rodgers, soprano; William Shimell, baritone; Liverpool Philharmonic Choir; Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; EMI Eminence CD EMX 2142 (Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, July 27–29, 1988)

- Richard Hickox—Marshall (sop)/Roberts (bar)/LS Chorus/Philharmonia; Virgin VC7 90843-2 (All Saints Church, Tooting, Feb. 27 to March 2, 1989)

- Bernard Haitink—Felicity Lott, soprano; Jonathan Summers, baritone; with London Philharmonic Choir; Cantilena; London Philharmonic; EMI CDC 7 49911 2 (Abbey Road, March 19–21, 1989)

- Bryden Thomson—Kenny (sop)/Rayner Cook (bar)/LS Chorus/LSO; Chandos CHAN 8764 (St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead, June 19–22, 1989)

- Leonard Slatkin—Valente (sop)/Allen (bar)/Philharmonia Chorus/Philharmonia; RCA Red Seal 09026-61197-2 (Abbey Road, June 19–20, 1992)

- Sir Andrew Davis—Roocroft (sop)/Hampson (bar)/BBC Symphony Chorus/BBC SO; Teldec 4509-94550-2 (Blackheath Halls, London, Feb. 1994)

- Slatkin—Rodgers (sop)/Keenlyside (bar)/choruses/BBC SO; BBC Music Magazine MM 244 (Royal Albert Hall, Sept. 10, 2001)

- Robert Spano, conductor—Christine Goerke, soprano; Brett Polegato, baritone; Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus; Telarc CD 80588 (Symphony Hall, Atlanta, Nov. 10–11, 2001); winner of 2003 Grammy Award for Best Classical Album

- Paul Daniel, conductor—Rodgers, soprano; Christopher Maltman, baritone; with Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra& Chorus; Naxos 8.557059 (Poole Arts Centre, Jan. 8–10, 2002)

- Hickox—Gritton (sop)/Finley (bar)/LS Chorus/LSO; Chandos CHSA 5047 (Barbican Hall, June 3–4, 2006)

- Howard Arman—McGreevy (sop)/Hakala (bar)/MDR Rundfunkchor/MDR Sinfonie-Orchester; Querstand VKJK 0731 (Gewandhaus, Leipzig, Feb. 4, 2007)

- Sir Mark Elder, conductor—Katherine Broderick, soprano; Roderick Williams, baritone; Hallé Orchestra and Choir; Hallé CD HLL 7542 (Bridgewater Hall, March 2014)

- Martyn Brabbins—Llewellyn (sop)/Farnsworth (bar)/BBC Symphony Chorus/BBC SO; Hyperion CDA 68245 (Blackheath Halls, London, Oct. 14–15, 2017)

- Andrew Manze—Fox (sop)/Stone (bar)/Liverpool Phil Choir/RLPO; Onyx 4185 (Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, Nov. 2017)