تل أبو هريرة | |

Shown within Near East  Tell Abu Hureyra (Syria) | |

| Location | Raqqa Governorate, Syria. |

|---|---|

| Region | Lake Assad |

| Coordinates | 35°51′58″N 38°24′00″E / 35.866°N 38.400°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 11,000 BCE |

| Abandoned | c. 5,000 BCE |

| Periods | Epipaleolithic—Neolithic |

| Cultures | Natufian culture |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1972–1973 |

| Archaeologists | Andrew M. T. Moore, Gordon Hillman, Anthony Legge |

| Condition | flooded by Lake Assad |

Tell Abu Hureyra (Arabic: تل أبو هريرة) is a prehistoric archaeological site in the Upper Euphrates valley in Syria. The tell was inhabited between 13,300 and 7,800 cal. BP[1] in two main phases: Abu Hureyra 1, dated to the Epipalaeolithic, was a village of sedentary hunter-gatherers; Abu Hureyra 2, dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, was home to some of the world's first farmers.[2] This almost continuous sequence of occupation through the Neolithic Revolution has made Abu Hureyra one of the most important sites in the study of the origins of agriculture.

The site is significant because the inhabitants of Abu Hureyra started out as hunter-gatherers but gradually moved to farming, making them the earliest known farmers in the world.[2] Cultivation started at the beginning of the Younger Dryas period at Abu Hureyra. Evidence uncovered at Abu Hureyra suggests that rye was the first cereal crop to be systematically cultivated. In light of this, it is now believed that the first systematic cultivation of cereal crops was around 13,000 years ago.[3]

During the Late Glacial Interstadial, Abu Hureyra site experienced climatic change.[2] Due to lake level changes and aridity, the vegetation expanded into lower areas of the fields. Abu Hureyra accumulated vegetation that consisted of grasses, oaks, and Pistacia atlantica trees.[2] The climate changed from warm and dry months to abruptly cold and dry months.[3]

History of research

The site was excavated as a rescue operation before it was flooded by Lake Assad, the reservoir of the Tabqa Dam which was being built at that time. The site was excavated by Andrew M. T. Moore in 1972 and 1973. It was limited to only two seasons of fieldwork. Despite the limited time frame, a large amount of material was recovered and studied over the following decades. It was one of the first archaeological sites to use modern methods of excavation such as "flotation", which preserved even the tiniest and most fragile plant remains.[2][4] A preliminary report was published in 1983 and a final report in 2000.[2]

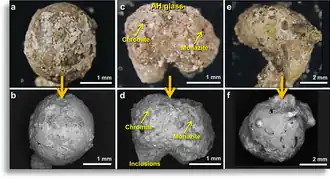

Since around 2012 Moore and others have published several papers reporting on meltglass, nanodiamonds, microspherules, and charcoal and high concentrations of iridium, platinum, nickel, and cobalt from the site of Abu Hureyra, which they attribute to an impact event that destroyed the village around 10,800 BC.[5][6][1]

Location and description

Abu Hureyra is a tell, or ancient settlement mound, in modern-day Raqqa Governorate in northern Syria. It is on a plateau near the south bank of the Euphrates, 120 kilometres (75 mi) east of Aleppo. The tell is a massive accumulation of collapsed houses, debris, and lost objects accumulated over the course of the habitation of the ancient village. The mound is nearly 500 metres (1,600 ft) across, 8 metres (26 ft) deep, and contained over 1,000,000 cubic metres (35,000,000 cu ft) of archaeological deposits.[4]: 42 Today the tell is inaccessible, submerged beneath the waters of Lake Assad.[7]

Occupation history

First occupation

The village of Abu Hureyra had two separate periods of occupation: An Epipalaeolithic settlement and a Neolithic settlement. The Epipaleolithic, or Natufian, settlement was established c. 13,500 years ago.[2] During the first settlement, the village consisted of small round huts, cut into the soft sandstone of the terrace. The roofs were supported with wooden posts, and roofed with brushwood and reeds.[4]: 40–41 Huts contained underground storage areas for food. The houses that they lived in were subterranean pit dwellings.[3] The inhabitants are probably most accurately described as "hunter-collectors", as they didn't only forage for immediate consumption, but built up stores for longterm food security. They settled down around their larder to protect it from animals and other humans. From the distribution of wild food plant remains found at Abu Hureyra it seems that they lived there year-round. The population was small, housing a few hundred people at most—but perhaps the largest collection of people permanently living in one place anywhere at that time.

The inhabitants of Abu Hureyra obtained food by hunting, fishing, and gathering of wild plants. Gazelle was hunted primarily during the summer, when vast herds passed by the village during their annual migration.[4]: 41–42 These would probably be hunted communally, as mass killings also required mass processing of meat, skin, and other parts of the animal. The huge amount of food obtained in a short period was a reason for settling down permanently: it was too heavy to carry and would need to be kept protected from weather and pests.

Other prey included large wild animals such as onager, sheep, and cattle, and smaller animals such as hare, fox, and birds, which were hunted throughout the year. Different plant species were collected, from three different eco-zones within walking distance (river, forest, and steppe). Plant foods were also harvested from "wild gardens" with species gathered including wild cereal grasses such as einkorn wheat, emmer wheat, and two varieties of rye.[4]: 41 Several large stone tools for grinding grain were found at the site.

Abu Hureyra 1 had a variety of crops that made up the system. Their resources consisted of 41% Rumex and Polygonum, 43% rye and einkorn, and the remaining 16% lentils.[8]

Depopulation

After 1,300 years the hunter-gatherers of the first occupation mostly abandoned Abu Hureyra, probably because of the Younger Dryas, an intense and relatively abrupt return to glacial climate conditions which lasted over 1,000 years,[4] or because of the purported impact event.[5] The drought disrupted the migration of the gazelle and destroyed forageable plant food sources. The inhabitants might have moved to Mureybet, less than 50 km to the northeast on the other side of the Euphrates,[9] which expanded dramatically at this time.

Second occupation

In comparison to Abu Hureyra 1, Abu Hureyra 2 had a different accumulation of resources, consisting of 25% Rumex/Polygonum, 3.7% rye/einkorn, 29% barley, 23.5% emmer, 9.4% wheat-free threshing, and 9.4% lentils.[8]

It is from the early part of the Younger Dryas that the first indirect evidence of agriculture was detected in the excavations at Abu Hureyra, although the cereals themselves were still of the wild variety.[10][11][12][13] It was during the intentional sowing of cereals in more favourable refuges like Mureybet that these first farmers developed domesticated strains during the centuries of drought and cold of the Younger Dryas. When the climate abated about 9500 BCE they spread all over the Middle East with this new bio-technology, and Abu Hureyra grew to a large village eventually with several thousand people. The second occupation grew domesticated varieties of rye, wheat and barley, and kept sheep as livestock. The hunting of gazelle decreased sharply, probably due to overexploitation that eventually left them extinct in the Middle East. At Abu Hureyra they were replaced by meat from domesticated animals. The second occupation lasted for about 2,000 years.

Transition from foraging to farming

Some evidence has been found for cultivation of rye from 11050 BCE[2] in the sudden rise of pollen from weed plants that typically infest newly disturbed soil. Peter Akkermans and Glenn Schwartz found this claim about epipaleolithic rye, "difficult to reconcile with the absence of cultivated cereals at Abu Hureyra and elsewhere for thousands of years afterwards".[14] It could have been an early experiment that didn't survive and continue. It has been suggested that drier climate conditions resulting from the beginning of the Younger Dryas caused wild cereals to become scarce, leading people to begin cultivation as a means of securing a food supply. Results of recent analysis of the rye grains from this level suggest that they may actually have been domesticated during the Epipalaeolithic. It is speculated that the permanent population of the first occupation was fewer than 200 individuals.[15] These individuals occupied several tens of square kilometers, a rich resource base of several different ecosystems. On this land they hunted, harvested food and wood, made charcoal, and may have cultivated cereals and grains for food and fuel.[15]

The first domesticated morphologic cereals came about at the Abu Hureyra site around 10,000 years ago.[8]

Agriculture

The village of Abu Hureyra had impressive agricultural advances for the time period. The rapid growth of farming led to the development of two different domesticated forms of wheat, barley, rye, lentils, and more due in part to a sudden cool period in the area.[16] The cool period affected the supply of wild animals such as gazelle, which at the time was their main source of protein. Since their food supply became scarce it was critical that they find a way to provide for the population, this led to extensive agricultural efforts as well as the domestication of sheep and goats to provide a steady protein source.[16] Another helpful factor was the ability to grow legumes, which fix nitrogen levels in the soil. This improved the fertility of the soil and allowed for the crop plants to flourish.[16]

This massive increase in agriculture had a cost. Those who lived in the village of Abu Hureyra experienced several injuries and skeletal abnormalities. These injuries mostly came from the way the crops were harvested. In order to harvest the crops the people of Abu Hureyra would kneel for several hours on end. The act of kneeling for long durations would put the individuals at risk for injuring the big toes, hips, and lower back.[17] There was cartilage damage in the toe that was so severe the metatarsal bones would rub together. In addition to this injury another common injury was for the last dorsal vertebra to be damaged, crushed, or out of alignment due to the pressure used during the grinding of grains.[18] These skeletal abnormalities also can be found on the teeth of the Abu Hureyra people. Since the grain was stone ground many flakes of stone would still be left in the grain which over time would wear down the teeth. In rare cases women would have large grooves in their front teeth which suggests they used their mouth as a third hand while weaving baskets. This dates basket weaving as far back as 6500 BC and the fact so few women had these grooves shows that basket weaving was a rare skill to have.[19] These baskets were extremely important to the success of the agriculture because the baskets were used to collect or spread seeds, and were also used to collect or distribute water.[17]

See also

- Battle of Siffin (657 CE, First Fitna). Siffin has been identified with Abu Hureyra.

References

- 1 2 Hai Cheng; et al. (8 September 2020). "Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics". PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007869117. hdl:10261/240073.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Moore, Andrew M. T.; Hillman, Gordon C.; Legge, Anthony J. (2000). Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-19-510806-X.

- 1 2 3 Hillman, Gordon; Hedges, Robert; Moore, Andrew; Colledge, Susan; Pettitt, Paul (27 July 2016). "New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates". The Holocene. 11 (4): 383–393. doi:10.1191/095968301678302823. S2CID 84930632.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mithen, Steven (2006). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20000-5000 BC (paperback ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01570-3.

- 1 2 3 Moore AM, Kennett JP, Napier WM, Bunch TE, Weaver JC, LeCompte M, Adedeji AV, Hackley P, et al. (6 March 2020). "Evidence of Cosmic Impact at Abu Hureyra, Syria at the Younger Dryas Onset (~12.8 ka): High-temperature melting at >2200 °C" (PDF). Scientific Reports (published 6 March 2020). 10 (1): 4185. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.4185M. doi:10.1038/S41598-020-60867-W. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7060197. PMID 32144395. Wikidata Q90119243.

The wide range of evidence supports the hypothesis that a cosmic event occurred at Abu Hureyra ~12,800 years ago, coeval with impacts that deposited high-temperature meltglass, melted microspherules, and/or platinum at other YDB sites on four continents.

- ↑ Fernandez S (6 March 2020). "Fire from the Sky" (Press release). University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

Based on materials collected before the site was flooded, Kennett and his colleagues contend Abu Hureyra is the first site to document the direct effects of a fragmented comet on a human settlement.

- ↑ Becker, Jeffrey (18 July 2018). "Tell Abu Hureyra: a Pleiades place resource". Pleiades: a gazetteer of past places. Clifflena Tiah. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox, George (February 2009). "Late Pleistocene and early Holocene climate and the beginnings of cultivation in northern Syria". Archaeology. 19 (1): 156. Bibcode:2009Holoc..19..151W. doi:10.1177/0959683608098961. S2CID 129444462. ProQuest 220530920.

- ↑ Mithen, After the Ice, p. 62: "It seems likely that those who abandoned Abu Hureyra simply crossed the river and began a new village at Mureybet"

- ↑ Hillman, Gordon C. (2000). "Overview". Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra. By Moore, A.M.T.; Hillman, G.C.; Legge, A.J. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 420–421.

- ↑ Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2002). "The Natufian culture and the early Neolithic: Social and economic trends in Southwestern Asia". In Bellwood, P.; Renfrew, C. (eds.). Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis. McDonald Institute Monographs. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. pp. 113–126.

- ↑ Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2002). "Natufian". In Fitzhugh, B.; Habu, J. (eds.). Beyond Foraging and Collecting: Evolutionary Change in Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. pp. 91–149.

- ↑ Dow, Olewiler and Reed 2005

- ↑ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans; Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The archaeology of Syria: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-521-79666-8. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- 1 2 Hillman, Gordon C.; A. J. Legge; P. A. Rowle-Conwy (1997). "On the Charred Seeds from Epipalaeolithic Abu Hureyra: Food or Fuel?". Current Anthropology. 38 (4): 651–655. doi:10.1086/204651. S2CID 144151770.

- 1 2 3 "Origins of agriculture – Early development". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- 1 2 "Abu Hureyra: Agriculture in the Euphrates Valley". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ↑ "The Eloquent Bones of Abu Hureyra – Documents – The Best Way to Share & Discover Documents". DocGo.Net. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ↑ "No. 960: Grain in Abu Hureyra". www.uh.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

External links

Media related to Abu Hureyra at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abu Hureyra at Wikimedia Commons- "World's first farming found in Near East". British Archaeology. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "First farmers discovered". BBC News. 28 October 1999. Retrieved 9 May 2008.