| Acocks Green | |

|---|---|

Broad Road, Acocks Green | |

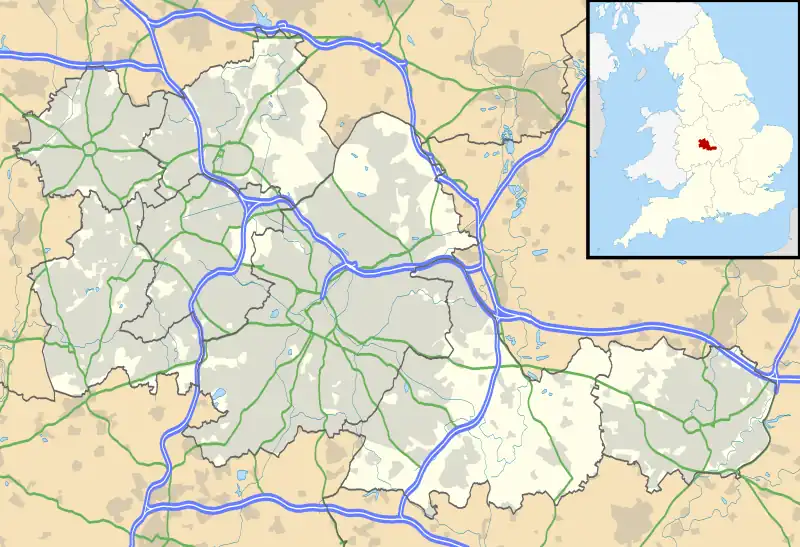

Acocks Green Location within the West Midlands | |

| Area | 3.800 km2 (1.467 sq mi) |

| Population | 24,500 (ward - 2021 Census)[1] |

| • Density | 6,447 per km² |

| OS grid reference | SP118833 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Shire county | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B27 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Acocks Green is a suburban area and ward of southeast Birmingham, England. It is named after the Acock family, who built a large house there in 1370. It is occasionally spelled "Acock's Green". It has frequently been noted on lists of unusual place names.[2]

Stockfield in the north of the ward was once a separate village. It merged with Acocks Green after housing development in the 20th century. The 2021 census gives a population of 24,500 for Acocks Green ward.[lower-alpha 1] The ward covers an area of 3.8 square kilometres (1.47 sq mi).[3]

History

Acocks Green developed north of the current centre at the roundabout where the Warwick Road meets Shirley and Westley Roads. This area was known as Tenchlee or Tenelea, meaning 'ten clearings'. The settlement that developed here has completely disappeared. Hyron Hall and Broom Hall were moated manor houses in the area. The Fox Hollies name derives from the time the Fox family bought the farm belonging to the atte Holies in the 15th century. The earliest known reference to Acocks Green is in the Yardley Parish Register of 1604. In 1626, Acocks Green House and other estates were given by Richard Acock to his son as a wedding gift. In 1725, the Warwick Road was turnpiked. At the end of the 18th century, the Warwick and Birmingham Canal was cut through the northern edge of Acocks Green, with wharves being constructed at Stockfield Road and Yardley Road. The increased prosperity brought by the canal led to the construction of farms and large residences.

Acocks Green began to expand following the opening of the Birmingham to Oxford Railway in 1852. At this time there were three hamlets along the Warwick Road; Flint Green, Acocks Green, and Westley Brook. As the hamlet of Acocks Green was closer to the railway station it developed faster than the others. Westley Brook became the centre of modern Acocks Green.

In 1911, the parish of Yardley, of which Acocks Green was a part, was absorbed into Birmingham. Birmingham was in need of housing and in the mid-1920s, municipal housing was built on the fields surrounding Acocks Green, resulting in a large increase in the population. Many new residents were unwelcome and existing residents moved away leading to the nickname Snobs Green.[4] Acocks Green benefited from an increase in commerce brought about by the newcomers. It developed into a major shopping area and churches and meeting halls were extended to accommodate more people.

Trams arrived in Acocks Green in 1916, first terminating at Broad Road before reaching The Green in 1922. The centre of Acocks Green was remodelled in 1932, and a large island incorporating the tram terminus was created. After the tram service ended, the island was grassed over.

Acocks Green was the location for a custom-built factory which made parts for the Bristol Hercules radial engines. Construction of the factory commenced in late 1936 on the site of Westwood's market gardening business near the canal. The factory was the Rover shadow factory and it was operational by July 1937. The factory was visited by King George VI in March 1938.[5] Towards the end of World War II, the factory began to produce Meteor tank engines and the Meteorite engine, and thus became a target for German bombers.[6]

The Stockfield Estate

The Stockfield Estate was one of Birmingham's many interwar housing estates built by the city council during the 1920s and 1930s to rehouse people from inner-city slums. The houses proved popular thanks to the inclusion of electricity, running water, indoor toilets, bathrooms and gardens. The houses, constructed from concrete and designed in the 'Parkinson' style, were declared defective by law in 1985 and structural tests concluded that damage was so severe that repair would not be possible. This meant that the 477 houses had to be demolished, however, Birmingham City Council did not have the financial services available to carry out the work. Residents of the estate set up an Estate Development Group and architects Webb Seeger Moorhouse were invited to prepare a masterplan for the estate. The masterplan and the proposal to establish a community association were publicly announced in October 1989. Residents unanimously approved the plans. Stockfield Community Association was formed in 1991 and a redevelopment partnership was then formed between the Community Association, Birmingham City Council, Halifax Building Society and Bromford Carinthia Housing Association, with Anthony Collins Solicitors and Webb Seeger Moorhouse Community Architects giving support. Wimpey Homes were appointed developers and work on the first phase of the estate commenced in July 1991. This was met with opposition from some residents refusing to move and the crime on the estate was so bad that the washing machine in the show home provided by Wimpey was stolen.[7]: 11 The first phase, saw 17 Bromford family homes for rent, opened in the summer of 1991 by the Lord Mayor of Birmingham. By 1998, all four phases of the estate were completed.[7]

Demography

The 2001 Population Census recorded that there were 26,635 people living in Acocks Green with a population density of 5,580 people/km2. The 1991 Population Census recorded 26,087 residents living in the ward, a decline of 6.7% from 1981.[8] 51.5% of the population is female and 48.5 is male. 19.6% (5,188) of the ward's population consists of ethnic minorities compared with 29.6% for Birmingham in general. 80.4% of the population are White. Chinese was the smallest ethnic group at 0.7%, compared with the Birmingham average of 1.1%. 13% of the ward's population was born outside the United Kingdom, compared with the Birmingham average of 16.5% and the national average of 9.3%. Christianity was the most prominent religion in the ward at 64.3%, above the city average of 59.1%. Islam was the second most selected religion at 7.7%, although "No Religion" had a higher percentage at 13.7%.

98.8% of the population live in households, which is above the Birmingham average of 98.3% and the national average of 98.2%. 1.2% live in communal establishments. There were 11,008 occupied households in the ward at the time of the census with an average of 2.4 people per household, equal to the national average. 305 households were vacant. 57.2% of the total households were owner-occupied, below the city average of 60.4% and the national average of 68.7%. The majority of the houses in Acocks Green were terraced (39%): semi-detached houses were also common in the area (36.4%).

17.5% of people are of a pensionable age and 58.2% are of a working age. 9.1% of the ward population was unemployed, above the city average of 6.8% and the national average of 4.1%. 36.6% of the unemployed had been in such a situation for the long term, and 13.5% had never worked. The majority of those that were employed worked in the manufacturing sector (18.6%). Wholesale & Retail Trade and Vehicle Repairs Finance and Real Estate & Business Activities were both major employment sectors in the area at 16.4%. The largest employer based in Acocks Green was Eaton Electric Ltd, employing approximately 750 people until its closure in 2018.[9]

Politics

As of 6 May 2022 the Acocks Green Ward is represented on Birmingham City Council by two Liberal Democrat councillors.

Nationally, Acocks Green is part of Birmingham, Yardley constituency[lower-alpha 2] represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 2015 by Jess Phillips of the Labour Party.[lower-alpha 3]

Education

Within its borders are EYFS providers seven primary schools and two secondary schools.

Acocks Green Primary School was created in 2004 upon the amalgamation of Acocks Green Junior School and Acocks Green Infant School. It is located in buildings dating to 1908.[10] It was opened in 1909 by Worcestershire County Council and was transferred to Birmingham City Council in 1911. The school consisted of Boys, Girls and Infants departments, but in 1932 it was reorganised into Senior Mixed and Junior Mixed departments. The Senior Mixed department became a separate school in 1945 and the Junior Mixed department became a primary school at the same time.[11] It currently has approximately 480 pupils.

The Cottesbrooke Infant and Junior schools opened on 6 September 1968 as a combined school. As the school was so oversubscribed, which resulted in the use of the local church hall for lessons, it was decided to split the school into an infant school and a junior school. The infant school remained in the original school buildings whilst the junior school was moved over the road with the original headteacher taking charge.[12] Cottesbrooke Infant School has 329 pupils whilst Cottesbrooke Junior School has 220.

Holy Souls Primary School is a voluntary aided Roman Catholic primary school. It is run by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham in partnership with Birmingham Local Education Authority. The school was established in 1907 and moved into its current premises in 1968.[13] There are 401 pupils on roll.

Oaklands Primary School, which was a primary school on Dolphin Lane, was constructed in 1928 and opened in 1929 as Oaklands County Primary School. It was expanded in 1932. In 1950, one of the timber buildings which formed the infants block was dismantled and reassembled in the newly constructed Gilbertstone estate to form Gilbertstone Primary School.[14] It currently has 335 pupils on roll.

Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School is a specialist secondary school with a sixth form centre. Construction commenced in 1955 and the school was opened in 1957. The school is named in memory of Archbishop Edward Ilsley, who built the first church in Acocks Green.[15]

Ninestiles Academy has over 1,300 laptop computers. It is attached to Fox Hollies Leisure Centre, which complements Acocks Green's other sports, gym and recreational facilities.

Fox Hollies School and Performing Arts College is a special school and used to be in the western end of the ward, but relocated to Moseley.

Kimichi School is an independent music school sited on Yardley Road, which opened in 2014 on the site of the former Eastbourne House School. Adult education takes place at Stone Hall, Archbishop Ilsley Technology College, Ninestiles Technology College, and Fox Hollies Leisure Centre. City College run an IT training facility from the Green. There is a yoga institute on Westley Road.

Places of interest

Acocks Green also has numerous parks and green spots, including Fox Hollies Park in the south which is home to a man-made lake called Round Pool.

The roundabout where Warwick Road meets Shirley Road and Westley Road, despite being a tram and bus terminus until the 1950s, is called The Green by most locals. This is the main shopping area in Acocks Green. Most of the general retail shops are located here and further along Warwick Road. There is also a library and a bowling alley. Outside The Green you will not find many shops except convenience stores and off-licences, although there is a large modern bingo hall located on Stockfield Road.

Acocks Green has seven churches including St Mary the Virgin, Acocks Green, Holy Souls, a Methodist church on Shirley Road, a Baptist church on Yardley Road and the Ghamkol Sharif Mosque. There is a large cultural diversity in Acocks Green with a mix of people from all religions and races. In recent years, Acocks Green has begun to see an increase in Polish residents.

Gospel Lane Skatepark was opened to the public on 12 August 2006.[16] It was created using Neighbourhood Renewal Fund grants and through the advice of youngsters who would use the park. The British Legion have a local office and club in the ward. Hall Green Little Theatre is also located in Acocks Green.

Notable residents

- Jasper Carrott, entertainer

- Dave Willetts, singer in musicals, was born in Marston Green in 1952 and was brought up in Acocks Green. While working for British Leyland, he got involved in amateur drama and his ability was spotted. He sang in the lead role of Valjean in Les Misérables in 1986, and took over the lead role from Michael Crawford in The Phantom of the Opera, and is famous as a top class musicals singer.[17]

- Dave Pegg, musician and record producer, perhaps most well known as the bass guitarist and longest serving member of Fairport Convention

Transport

Acocks Green has transport links to Birmingham city centre and Solihull. Birmingham's Moor Street and Snow Hill stations, as well as Solihull station can all be reached in around ten minutes by train from Acocks Green railway station. Spring Road railway station on the Stratford-Upon-Avon line also goes to Moor Street and Snow Hill.

Many bus routes are operated by National Express West Midlands from Acocks Green Bus Garage on Fox Hollies Road, including the Outer Circle (11A/11C), which is the longest urban bus route in any European city at 27 miles long. Routes that serve Acocks Green are:

- Service 1 (Five Ways – Acocks Green via Edgbaston & Moseley)

- Service 4 (Birmingham – Solihull Station via Acocks Green)

- Service 4A (Birmingham – Gospel Oak/Solihull via Acocks Green)

- Service 11A/C (Birmingham Outer Circle)

- Service 32 (Shirley – Lyndon via Acocks Green)

- Service 36 (Heartlands Hospital – Small Heath Station via Tyseley & Acocks Green)

- Service 41 (Q.E Hospital – Acocks Green via Moseley & Sparkhill)

- Service A12 (Acocks Green – Solihull via Olton)

The area can become congested and there have been calls for a bypass to ease pressure on the roads. Businesses in the shopping area have opposed the idea because of concerns over losing passing trade. Another proposal put forward to alleviate traffic congestion in the centre, whilst also making the area more pedestrian friendly, is to introduce a type of high street design known as Shared Space.[18]

Public services

Acocks Green is served by West Midlands Police. The nearest police station with public access is Stechford.[19] Acocks Green police station remains in use but is scheduled for disposal.[20]

Acocks Green library was opened on 14 June 1932 by the Lord Mayor of Birmingham, John Burman. It was the 25th branch library in Birmingham.[21] Outside the library is the Acocks Green war memorial.[22]

Listed buildings

The Grade II listed police station and courthouse building on Yardley Road was designed by the Worcestershire county architect, Albert Vernon Rowe and built for the Worcestershire Constabulary in 1909. The complex also originally provided residential accommodation for officers. The façade is of red brick in a Queen Anne revival style. A three-storey octagonal corner turret at the Alexander Road end has keyed oculi and a domed roof. A cartouche depicting the three pears of the Worcestershire coat of arms is in the centre pediment facing Yardley Road.[23]

Other Grade II listed buildings are cottages in Arden Road,[24][25] and the Baptist Church on Yardley Road[26] together with its church hall on Alexander Road.[27] Locally listed buildings include the former fire station (Grade B) and caretaker's house (Grade A) on Alexander Road, a house on the corner of Elmdon Road, and the library on Shirley Road (Grade A). In Fox Hollies Park is a Bronze Age burnt mound with Scheduled Ancient Monument status.[28]

Notes

- ↑ Rounded to the nearest 100 people

- ↑ A borough constituency (for the purposes of election expenses and type of returning officer)

- ↑ As with all constituencies, the constituency elects one member of parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election at least every five years.

References

- ↑ "Profile preview Acocks Green".

- ↑ Parker, Quentin (2010). Welcome to Horneytown, North Carolina, Population: 15: An insider's guide to 201 of the world's weirdest and wildest places. Adams Media. p. 1. ISBN 9781440507397.

- ↑ "Acocks Green (Ward, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ↑ Hulse, Cathrina (28 July 2019). "Acocks Green through the years – the Birmingham village once known as Snobs Green". birminghammail.co.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ Acocks Green History Society: The Rover shadow factory Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Acocks Green History Society: Acocks Green's vulnerability Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "The Stockfield Story" (PDF). Stockfield Community Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ Acocks Green Ward Development Plan Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Birmingham Economy: Acocks Green

- ↑ "School History". Acocks Green Primary School. Archived from the original on 22 March 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ Records of Acocks Green County Primary School, 1909-1956, Birmingham City Archives, transferred by the Chief Education Officer in November 1973 [Catalogue Reference: S1]

- ↑ "History". Cottesbrooke Junior School. Archived from the original on 28 April 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ "About our School". Holy Souls Catholic Primary School. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ 'Public Education: Schools ', A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham (1964), pp. 501-548. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=22984. Date accessed: 2 May 2008.

- ↑ "History of Our School". Archbishop Ilsley Catholic Technology College. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ "Welcome to Yardley : Gospel Lane Skatepark". birmingham.gov.uk. 25 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007.

- ↑ Jones, Alison (31 May 2013). "Willetts still on song". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "Campaign for the Regeneration of Acocks Green Centre". acocksgreenfocusgroup.org.uk. Acocks Green Focus Group. 11 March 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ "Acocks Green". West Midlands Police. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ↑ Sandiford, Josh (23 October 2023). "Thirty police buildings to close amid 'significant cost pressures' - full list". Birmingham Live. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ↑ "Acocks Green Library: its history". Acocks Green History Society. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ "Acocks Green WW1 And WW2". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Acocks Green Police Station and former courthouse (Grade II) (1459333)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ivy Cottage, The Cottage, Arden Road (Grade II) (1075744)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gladstone Cottage, Arden Road (Grade II) (1291294)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Baptist Church, Yardley Road (Grade II) (1234473)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Baptist Church Hall, Alexander Road (Grade II) (1276115)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ Birmingham City Council: Acocks Green Today Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine