Linois's expedition to the Indian Ocean was a commerce raiding operation launched by the French Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. Contre-Admiral Charles-Alexandre Durand Linois was ordered to the Indian Ocean in his flagship Marengo in March 1803 accompanied by a squadron of three frigates, shortly before the end of the Peace of Amiens. When war between Britain and France broke out in September 1803, Marengo was at Pondicherry with the frigates, but escaped a British squadron sent to intercept it and reached Isle de France (now Mauritius). The large distances between naval bases in the Indian Ocean and the limited resources available to the British commanders in the region made it difficult to concentrate sufficient forces to combat a squadron of this size, and Linois was subsequently able to sustain his campaign for three years. From Isle de France, Linois and his frigates began a series of attacks on British commerce across the Eastern Indian Ocean, specifically targeting the large convoys of East Indiamen that were vital to the maintenance of trade within the British Empire and to the British economy. Although he had a number of successes against individual merchant ships and the small British trading post of Bencoolen, the first military test of Linois squadron came at the Battle of Pulo Aura on 15 February 1804. Linois attacked the undefended British China Fleet, consisting of 16 valuable East Indiamen and 14 other vessels, but failed to press his military superiority and withdrew without capturing a single ship.

In September 1804, Linois attacked a small British convoy at Vizagapatam in the Bay of Bengal and captured one ship, but was again driven off by inferior British forces. The damage Marengo suffered on the return to Isle de France was so severe that she had to be overhauled at Grand Port, and after subsequent cruises in the Red Sea and in the central Indian Ocean, where Linois was again driven away from a large British convoy by inferior British forces, he attempted to return to Europe via the Cape of Good Hope. On the return journey, Linois's ships sailed into the cruising ground of a British squadron participating in the Atlantic campaign of 1806 and was captured by overwhelming forces at the action of 13 March 1806, almost exactly three years after leaving France. Linois's activities in the Indian Ocean had caused panic and disruption across the region, but the actual damage inflicted on British shipping was negligible and his cruise known more for its failures than its successes. In France, Napoleon was furious and refused to exchange Linois for captured British officers for eight years, leaving him and his crew as prisoners of war until 1814.

Background

During the early nineteenth century the Indian Ocean was a vital conduit of British trade, connecting Britain with its colonies and trading posts in the Far East. Convoys of merchant ships, including the large East Indiamen, sailed from ports in China, South East Asia and the new colony of Botany Bay in Australia, as well as Portuguese colonies in the Pacific Ocean.[1] Entering the Indian Ocean, they joined the large convoys of ships from British India that carried millions of pounds of trade goods to Britain every year.[2] Together these ships crossed the Indian Ocean and rounded the Cape of Good Hope, sailing north until eventually reaching European waters. Docking at one of the principal British ports, the ships unloaded their goods and took on cargo for the return journey. This often consisted of military reinforcements for the Army of the Honourable East India Company (HEIC), whose holdings in India were constantly expanding at the expense of neighbouring states.[3]

During the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1801), French frigates and privateers operated from the French Indian Ocean colonies of Isle de France and Réunion against British trade routes. Although protected by Royal Navy and the fleet of the HEIC, there were a number of losses among individually sailing ships, particularly the "country ships": smaller and weaker local vessels less able to defend themselves than the large East Indiamen.[4] Many of these losses were inflicted by privateers, in particular the ships of Robert Surcouf, who captured the East Indiaman Kent in 1800 and retired on the profits.[5] However, these losses formed only a tiny percentage of the British merchant ships crossing the Indian Ocean: the trade convoys continued uninterrupted throughout the conflict. In 1801 the short-lived Peace of Amiens brought an end to the wars, allowing France to reinforce their colonies in the Indian Ocean, including the Indian port-city of Pondicherry on the Bay of Bengal.[6]

Another feature of the French Revolutionary Wars was the effect of British blockade on French movements. The Royal Navy maintained an active close blockade of all major French ports during the conflict, which resulted in every French ship that left port facing attack from squadrons and individual ships patrolling the French and allied coasts. The losses the French Navy suffered as a result of this strategy were high, and the blockade was so effective that even movement between ports along the French coasts was restricted.[7] In the Indian Ocean however the huge distances between the French bases on Réunion and Isle de France and the British bases in India meant that close blockade was an ineffective strategy: the scale of the forces required to maintain an effective constant blockade of both islands, as well as the Dutch ports at the Cape of Good Hope and in the Dutch East Indies were too large to be worth their deployment to such a distant part of the world.[8] As a result, the French raiders operating from the Indian Ocean bases were able to travel with more freedom and less risk of interception than those in the Atlantic or Mediterranean.[9]

During 1802, tensions rose again between Britain and France, the latter country now under the rule of First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte. Aware that a return to war was almost inevitable, Napoleon ordered the French Navy to prepare a force for extended service in the Indian Ocean, a force that would be capable of inflicting significant losses on the British trade from the region.[10] The flagship of the squadron was to be the fast ship of the line Marengo, a 74-gun vessel commanded by Contre-Admiral Charles-Alexandre Léon Durand Linois.[11] Linois was a highly experienced officer who had been engaged with the British on a number of occasions during the French Revolutionary Wars: in May 1794, he was captured when his frigate Atalante was run down in the mid-Atlantic by HMS Swiftsure.[12] Rapidly exchanged, his next ship Formidable was captured after a fierce defence at the Battle of Groix, and the following year he was captured again in his new frigate Unité and subsequently participated in the disastrous Expédition d'Irlande in the ship of the line Nestor after a third prisoner exchange.[13] His most important battle was in July 1801, when he commanded the French squadron during their victory at the First Battle of Algeciras, where HMS Hannibal was captured. He was also in partial command at the defeat in the Second Battle of Algeciras four days later, but the action enhanced his reputation within the French Navy as a successful commander.[14] Marengo was accompanied by the frigates Atalante, Sémillante and French frigate Belle Poule 1802 (2) and the transports Côte d'Or and Marie Françoise. Ostensibly this squadron was despatched to the Indian Ocean to take possession of Pondicherry and install a new governor in the French Indian Ocean colonies, General Charles Decaen. The convoy carried 1,350 soldiers and a significant quantity of supplies for both the four-month journey to India and the anticipated extended operations that were to follow it.[15]

Movements in 1803

Linois's squadron departed Brest on 6 March 1803. The four-month journey to Pondicherry was interrupted by a fierce storm on 28 April, which caused Belle Poule to separate from the squadron and shelter in Madagascar for several days. The transports Côte d'Or and Marie Françoise were also detached in the high winds, and made their way separately to the destination.[16] The bad weather delayed the arrival of Linois's main squadron, and thus Belle Poule arrived in India first, on 16 June. Napoleon believed, and had assured Linois, that war with Britain was not likely until September, but relations broke down faster than expected and Britain began mobilising on 16 May, issuing a formal declaration of war two days later. As news could only travel at the same speed as a fast ship, it had not arrived in the Indian Ocean by the time of Belle Poule's arrival, although it was expected at any moment.[17] Colonel Louis Binot, who had sailed on the frigate, called on the British officials then operating the factories in Pondicherry to turn them over to the French as stipulated in the Treaty of Amiens, but was refused. The factory owners were under orders from Governor-General Lord Wellesley, in turn under orders from Lord Hawkesbury, to deny the French access to Pondicherry's commercial assets.[6] The French position was further weakened when a large British squadron, consisting of the ships of the line HMS Tremendous, HMS Trident and HMS Lancaster, the fourth-rate HMS Centurion and the frigates HMS Sheerness, HMS Concorde, HMS Dedaigneuse and HMS Fox anchored at Cuddalore, 20 miles (32 km) to the south of Pondicherry. This squadron had been sent from Bombay under Rear-Admiral Peter Rainier to watch French movements. On 5 July, Rainier had received word from Bombay, via Madras, that war was imminent although not yet declared, and had moved his ships to an anchorage within sight of Pondicherry in anticipation of the outbreak of war.[16]

Linois arrived at Pondicherry on 11 July to find Rainier's ships anchored nearby and most of the city's financial institutions still in British hands.[18] Trident and the brig HMS Victor were anchored in Pondicherry roads, although on Linois's arrival they sailed to join Rainier's squadron. The following day, Linois sent Captain Joseph-Marie Vrignaud and his own nephew on board Rainier's flagship with an invitation to breakfast the following morning, which was accepted.[19] At 10:00, the transport Marie François arrived in Pondicherry, having been separated in the storm, and she was followed at 18:00 by the brig Bélier. Bélier had been sent out from Brest on 16 March carrying, among other papers, copies of a speech made before the British Parliament by King George III that threatened conflict and orders from Napoleon to immediately sail for Isle de France in anticipation of the declaration of war.[20] Linois was instructed to deliver Decaen to the island, and prepare his ships on the Indian Ocean island for a lengthy raiding operation against British commerce in the region.[17] When dawn rose on 13 July, Rainier embarked on the 16-gun brig HMS Rattlesnake for his breakfast appointment, only to discover that Linois's ships had slipped away in the night.

Linois had escaped so swiftly that his anchors and boats had been left in the bay, where he had abandoned them rather than draw attention to his movements by drawing them in.[17] He had also just missed the transport Côte d'Or with its 326 soldiers, which arrived on the evening of 13 July and was swiftly surrounded by Centurion and Concorde. Detaching most of his squadron to Madras, Rainier waited off Pondicherry for further French movements and on 15 July spotted Belle Poule just off the coast. Linois had detached the frigate to investigate the anchorage at Madras, but she had been intercepted and followed by the frigate HMS Terpsichore, whose insistent shadowing had forced Captain Alain-Adélaïde-Marie Bruilhac to return to Pondicherry.[19] Belle Poule and Côte d'Or exchange signals during the morning, and at 11:00 the transport suddenly raised sails and departed the anchorage, Terpsichore pursuing closely. Early on 16 July, Terpsichore overtook the transport and fired several shots across her bow, forcing her captain to surrender. Bruilhac had used the distraction to sail Belle Poule to Isle de France without pursuit. Côte d'Or was returned to Pondicherry and, since there was no news of war from Europe, released on 24 July on condition that she only sail to Isle de France and no other destination. Dedaigneuse was detached to ensure that the transport followed these conditions and Rainier returned to Madras, joined by Dedaigneuse the following day once the transport's course was ensured. Rainier immediately ordered his ships to take on military supplies in preparation for military operations, although news of the declaration of war, made on 18 May, did not reach him until 13 September.[19]

By the time Rainier learned of the outbreak of war, Linois was already at Isle de France, where his ships had arrived without incident on 16 August. Decaen was installed as governor and some of the troops disembarked to reinforce the garrison, although Linois retained the rest on board his squadron. On the journey to India, Linois and Decaen had fallen out, and the effects of their distaste for one another would be a repeated feature of the following campaign.[20] Britain's declaration of war reached Isle de France at the end of August aboard the corvette Berceau, which Linois added to his squadron.[17] By 8 October his preparations were complete, and the French admiral issued his orders for his squadron to sail. Atalante was detached to raid shipping in the area of Muscat, an important Portuguese trading post. The rest of the squadron, except the troopships, was to sail with Linois to Réunion (soon to be renamed Île Bonaparte), where the garrison was reinforced.[17] It then sailed eastwards to the Dutch East Indies, diverting to raid British shipping lanes, where many merchant ships were still unaware of the outbreak of war. Linois's first combat cruise was successful, and he captured a number of undefended prizes from the country ships encountered en route to the East Indies.[21] In early December, shortly before he reached Batavia on Java, Linois stopped at the minor British trading town of Bencoolen. The local maritime pilot believed the squadron to be British and brought them into the harbour, anchoring them just outside the range of the port's defensive battery but within range of the small merchant ships clustered in the bay. These merchant ships recognised the French warships and fled, pursued closely by Berceau and Sémillante. Six were scuttled by their crews at Sellebar 2 miles (3.2 km) to the south and two more burnt by French landing parties after grounding. The French also destroyed three large warehouses containing cargoes of spices, rice and opium and captured three ships, losing two men killed when a cannon shot from the shore struck Sémillante. On 10 December the squadron arrived at Batavia for the winter, disembarking the remaining soldiers to augment the Dutch garrison.[21]

Pulo Aura

On 28 December 1803, carrying provisions for six months cruising, Linois's squadron left Batavia. Sailing northwards into the South China Sea, Linois sought to intercept the HEIC China Fleet, a large convoy of East Indiamen carrying trade goods worth £8 million (the equivalent of £749,000,000 as of 2024)[22] from Canton to Britain.[23] The annual convoy sailed through the South China Sea and the Straits of Malacca, gathering ships from other destinations en route and usually under the protection of an escort formed from Royal Navy ships of the line. However, the 1804 fleet had no escort: the outbreak of war had delayed the despatch of the vessels from Rainier's squadron.[24] Thus as the convoy approached the Straits of Malacca it consisted of 16 East Indiamen, 11 country ships and two other vessels guarded by only one small HEIC armed brig, Ganges. On 14 February, close to the island of Pulo Aura, the commodore of the convoy, Nathaniel Dance, was notified that sails were sighted approaching from the south-west. Suspicious, Dance sent a number of the East Indiamen to investigate, and rapidly discovered that the strange ships were the French squadron under Linois. Dance knew that his convoy would be unable to resist the French in combat and instead decided to bluff the French by pretending that a number of his large East Indiamen were disguised ships of the line.[8]

Dance formed his ships into a line of battle and ordered three or four of them to raise blue ensigns and the others red, giving the impression of a heavy escort by implying that the ships with blue ensigns were warships.[25] This ruse provoked a cautious response from Linois, who ordered his squadron to shadow the convoy without closing with them. During the night, Dance held position and Linois remained at a distance, unsure of the strength of the British convoy.[26] At 09:00, Dance reformed his force into sailing formation to put distance between the two forces and Linois took the opportunity to attack, threatening to cut off the rearmost British ships. Dance tacked and his lead vessels came to the support of the rear, engaging Marengo at long range. Unnerved by the sudden British manoeuvere, Linois turned and retreated, convinced that the convoy was defended by an overwhelming force.[27] Continuing the illusion that he was supported by warships, Dance ordered his ships to pursue Linois over the next two hours, eventually reforming and reaching the Straits of Malacca safely. There they were met several days later by two ships of the line sent from India.[28]

The engagement was an embarrassment for Linois, who insisted that the convoy was defended by up to eight ships of the line and maintained that his actions had saved his squadron from certain destruction.[29] His version of events was widely ridiculed by both his own officers and the authorities in Britain and France, who criticised his timidity and his failure to press the attack when such a valuable prize was within his reach.[8] Dance by contrast was lauded for his defence and rewarded with a knighthood and large financial gifts, including £50,000 divided among the officers and men of the convoy.[30] The engagement prompted a furious Napoleon to write to the Minister of Marine Denis Decrès:

All the enterprises at sea which have been undertaken since I became the head of the Government have missed fire because my admirals see double and have discovered, I know not how or where, that war can be made without running risks . . . Tell Linois that he has shown want of courage of mind, that kind of courage which I consider the highest quality in a leader.

— Emperor Napoleon I, quoted in translation in William Laird Clowes' The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume 5, 1900, [31]

Operations in the Indian Ocean

Arriving at Batavia in the aftermath of the engagement, Linois was the subject of criticism from the Dutch governors for his failure to defeat the China convoy. They also refused his requests to make use of the Dutch squadron stationed in port for future operations.[32] Rejoined by Atalante, Linois sold two captured country ships and resupplied his squadron, before sailing for Isle de France, Marengo arriving on 2 April. During the return journey, Linois had detached his frigates and they captured a number of valuable merchant ships sailing independently before joining the admiral at Port Louis, which Decaen had renamed Port Napoleon. On his arrival, Linois was questioned by Decaen about the engagement with the China Fleet and when Decaen found his answers unsatisfactory the governor wrote a scathing letter to Napoleon, which he despatched to France on Berceau.[33] Linois remained at Isle de France for the next two and a half months, eventually departing with Marengo, Atalante and Sémillante in late June, while Belle Poule was detached to cruise independently.[34]

Second cruise of Linois

Linois initially sailed for Madagascar, seeking to prey on British trade rounding the Cape of Good Hope. Bad weather forced him to shelter in Saint Augustin for much of the next month, taking on fresh provisions before departing to the Ceylon coast.[33] There he captured a number of valuable prizes, including Charlotte and Upton Castle, which were carrying rice and wheat, and which he sent to Isle de France to provide a ready store of food for the squadron.[35]

Linois's force gradually moved northwards into the Bay of Bengal and in late August passed Madras, remaining 60 nautical miles (110 km) off the coast to avoid an unequal encounter with Rainier's squadron. He investigated the harbours at Masulipatam and Cosanguay, making a number of small captures and subsequently cruising along Coastal Andhra in search of valuable convoys. Prisoners from one of the ships taken off Masulipatam on 14 September informed him that a valuable British convoy was anchored in the harbour at Vizagapatam, consisting of the frigate HMS Wilhelmina and two East Indiamen.[36]

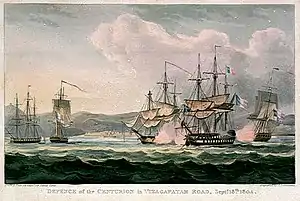

Arriving off Vizagapatam early on 15 September 1804, Linois discovered that Rainier, concerned by French depredations off the Indian coast, had substituted Wilhelmina for the larger and heavier HMS Centurion, a 50-gun fourth rate.[36] Also anchored in the harbour roads were the small East Indiamen Barnaby and Princess Charlotte. Centurion's captain, James Lind, was ashore and command rested with Lieutenant James Robert Phillips, who was suspicious of the new arrivals and fired on them as they came within range. Raising French flags, Linois's frigates closed on the anchored ships, coming under fire from a gun battery on shore.[37] Marengo remained beyond the sandbanks that marked the harbour entrance but still within long range of Centurion, unwilling to risk grounding his flagship in the shallow waters. Phillips issued urgent orders for the Indiamen to provide assistance, but was ignored: Barnaby drifted ashore and was wrecked when her captain cut her anchor cables while Princess Charlotte refused to participate in the engagement at all, remaining at anchor without making use of her 30 cannon.[38] The French ships temporarily withdrew for repairs at 10:45, but Centurion was even more severely damaged, drifting beyond the support of the shore batteries as the French returned to the attack at 11:15.[37] With the harbour exposed, Princess Charlotte surrendered to Sémillante as Atalante and Marengo continued to engage the British ship. By 13:15, with Centurion badly damaged and the prize secure, Linois decided to withdraw, easily outdistancing the limping British pursuit.[39] Linois subsequently came under criticism for his failure to annihilate the British warship, Napoleon later commenting that "France cared for honour, not for a few pieces of wood."[40]

With Marengo damaged and Rainier actively hunting for his squadron, Linois withdrew from the Bay of Bengal and returned to Isle de France. Rainier knew that his chances of discovering Linois in the open Indian Ocean were insignificant, and instead decided to keep watch for him off his principal base at Port Napoleon. A squadron was detached to the port, but Linois's scouts discovered the blockade before he arrived and he was able to safely reach Grand Port instead on 31 October.[41] Entering over the reefs that protected the anchorage, Marengo's deeper keel scraped on the coral. The ship's hull was badly damaged and her rudder torn off, requiring extensive repairs.[42] Linois was later joined by Captain Bruilhac in Belle Poule, who had captured a valuable merchant ship on his individual cruise in the Bay of Bengal.[43]

With his flagship severely damaged, Linois began an extensive series of repairs to Marengo, which was overhauled and beached to have her bottom and rudder replaced. The repairs lasted until May 1805, and the expense of feeding and accommodating the hundreds of sailors from the squadron placed a significant strain on Decaen's resources, despite the captured food supplies sent in by Linois during 1804.[35] To alleviate the pressure, Linois ordered Captain Gaudin-Beauchène in Atalante to cruise independently off the trade routes that passed the Cape of Good Hope and on 6 March detached Sémillante from the squadron entirely, sending Captain Léonard-Bernard Motard on a mission to the Philippines. He was then ordered to sail on across the Pacific to Mexico, to liaise with the Spanish officials there before returning to Europe around Cape Horn. Motard's mission to the Americas was brought to an end on 2 August 1805, when he encountered HMS Phaeton and HMS Harrier under Captain John Wood in the San Bernardino Strait, after resupplying for the Pacific voyage at San Jacinto. In a sharp engagement the British ships inflicted severe damage to Sémillante before being driven off by a Spanish fort overlooking the strait.[44] The damage was so severe that Motard abandoned the plans to sail for Mexico, returning to the Indian Ocean and continuing to operate from Isle de France against British trade routes until 1808.[45]

Third cruise of Linois

Departing Isle de France for the third and final time on 22 May 1805, Linois initially sailed northwest to the mouth of the Red Sea. Finding few targets, he turned eastwards and by July was again raiding shipping off the coast of Ceylon, accompanied by Belle Poule.[46] There on 11 July he discovered his richest prize yet, the 1200-ton (bm) East Indiaman Brunswick. Linois discovered Brunswick, under the command of Captain James Ludovic Grant, and the 935-ton (bm) country ship Sarah, under Captain M'Intosh. With the French advancing rapidly on the heavily laden merchant ships, Grant ordered Sarah to separate and attempt to shelter on the Ceylon coast. Linois detached Belle Poule to chase Sarah. M'Intosh ran Sarah onto the beach to avoid capture, the crew scrambling ashore as Sarah broke up in the heavy surf. Brunswick was slower than Sarah, and although Grant opened fire on Marengo the engagement was brief, Brunswick rapidly surrendering to the larger French vessel.[47] Grant was taken aboard Marengo and observed the French ship at close quarters, developing a negative opinion of Linois and his crew:

She sails uncommonly fast: but her ship's company, though strong in number, there being 800 men now on board, does not possess 100 effective seamen . . . There does not appear to be the least order or discipline amongst their people; all are equal, and each man seems equally conscious of their own superiority; and such is the sad state and condition of the Marengo that I may with safety affirm, she floats upon the sea as a hulk of insubordination, filthiness and folly.

— Captain James Ludovic Grant, [42]

In early 1805, Rainier had been replaced in command at Madras by Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, a more aggressive officer with a reputation of success against the French Navy.[48] Learning of Linois's reappearance off Ceylon, Pellew immediately despatched a squadron in search of him. Linois discovered the impending arrival of Pellew's ships from captured prisoners and departed westwards, successfully avoiding an encounter with the British force. After again cruising off the entrance to the Red Sea without success, Linois sailed southwards to intersect the trade routes between the Cape of Good Hope and Madras. During the journey, his squadron were caught in a heavy storm and Belle Poule lost her mizenmast. Linois was able to replace it, but the incident left him without any spare masts should either of his ships lose another. Without a full sailing rig, his ships were vulnerable to capture by faster and more agile British vessels, and Linois decided that protecting his masts was his most important priority.[42]

On 6 August 1805, Linois encountered his first significant prize since Brunswick, when he discovered a convoy of eleven large ships sailing eastwards along the trade route from the Cape to Madras at 19°09′S 81°22′E / 19.150°S 81.367°E. Closing to investigate the convoy, which was shrouded in fog, Linois was again cautious, unwilling to engage until he was certain that no Royal Navy ships lay among the East Indiamen.[49] At 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) distance it became clear that one of the ships was certainly a large warship, flying a pennant indicating the presence of an admiral on board. This ship was HMS Blenheim, a ship of the line built in 1761 as a 90-gun second rate but recently cut down to 74-guns. She was commanded by Captain Austen Bissell and flew the flag of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Troubridge, a prominent officer who had been sent to the Indian Ocean to assume command of half of Pellew's responsibilities after a political compromise at the Admiralty.[50] Troubridge's flagship was the convoy's only escort, leading ten East Indiamen through the Indian Ocean to Madras.[42]

As at Pulo Aura, the Indiamen formed line in preparation for Linois's attack, and once again Linois refused to engage them directly: Blenheim was a powerful ship capable of inflicting fatal damage on Marengo even if the French managed to defeat her, an uncertain outcome given the presence of the heavily armed merchant ships. Instead, Linois swung in behind the convoy, hoping to cut off a straggler. These manoeuveres were too complex for the poorly manned Brunswick, and she fell out of the French formation and was soon left behind, disappearing over the horizon.[51] At 17:30, Marengo pulled within range of the rearmost East Indiaman and opened a long-range fire, joined by Belle Poule. The rear ship Cumberland, a veteran of the Battle of Pulo Aura, was unintimidated and returned fire as Blenheim held position so that the convoy passed ahead and the French ships rapidly came up with her.[46] Opening a heavy fire with the main deck guns, Troubridge was able to drive the French ships off, even though his lower deck guns were out of service due to the heavy seas that threatened to flood through the lower gunports.[47] Linois, concerned for the safety of his masts, pressed on all sail and by 18:00 had gone beyond range of Blenheim's guns and overtaken the convoy, remaining within sight until nightfall.[46]

At midnight, the French ships crossed the bows of the convoy and by morning were 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) to windward, to the south. Troubridge maintained his line throughout the night and at 07:00 on 7 August 1805 he prepared to receive the French again as Linois bore down on the convoy.[52] Retaining their formation, the combined batteries of the Indiamen and Blenheim dissuaded Linois from the pressing the attack and he veered off at 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) distance, holding position for the rest of the day before turning southwards at 21:00 and disappearing.[46] Troubridge wanted to pursue in Blenheim, but was dissuaded by the presence of Belle Poule, which could attack the convoy while the ships of the line were engaged. He expressed confidence however that he would have been successful in any engagement and wrote "I trust I shall yet have the good fortune to fall in with him when unencumber'd with convoy".[49] Linois's withdrawal was prudent: his mainmast had been struck during the brief cannonade and was at risk of collapse if the engagement continued. Losses among the crew were light, Marengo suffering eight men wounded and Belle Poule none. British casualties were slightly heavier, a passenger on Blenheim named Mr. Cook was killed by langrage shot and a sailor was killed on the Indiaman Ganges by a roundshot. No British ships suffered anything more than superficial damage in the combat, and the convoy continued its journey uninterrupted, arriving at Madras on 23 August.[52]

Return to the Atlantic

Retiring from the encounter with Blenheim, Linois sailed westwards and arrived in Simon's Bay at the Dutch colony of Cape Town on 13 September. He was hoping there to join up with the Dutch squadron maintained at the Cape, but discovered that the only significant Dutch warship in the port was the ship of the line Bato, which was stripped down and unfit for service at sea.[53] Repairing the damage suffered in the August engagement and replenishing food and naval stores over the next two months, Linois was joined in October by Atalante. On 5 November a gale swept the bay and Atalante dragged her anchors, Captain Gaudin-Beauchène powerless to prevent his frigate driving ashore and rapidly becoming a total wreck. The crew were able to escape to shore in small boats and were then divided among Marengo and Belle Poule, with 160 men left to augment the garrison at Cape Town.[51] Linois's prize, the Brunswick, too was wrecked near Simon's Bay.

Leaving Simon's Bay on 10 November, Linois slowly sailed up the West African coast, investigating bays and estuaries for British shipping, but only succeeding in capturing two small merchant vessels.[53] He passed Cape Negro and Cape Lopez and obtained fresh water at Príncipe, before cruising in the region of Saint Helena. There he learned on 29 January 1806 from an American merchant ship that a British squadron had captured Cape Town. With the last safe harbour within reach in enemy hands and in desperate need of repair and resupply, Linois decided to return to Europe and slowly passed north, following the trade routes in search of British merchant shipping.[54] On 17 February, Marengo crossed the equator and on 13 March was in position 26°16′N 29°25′W / 26.267°N 29.417°W.[53]

Atlantic campaign of 1806

Unknown to Linois, his squadron was sailing directly into the path of a major naval campaign, the Atlantic campaign of 1806. In the aftermath of the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805, and the subsequent end of the Trafalgar Campaign at the Battle of Cape Ortegal on 5 November 1805, the British had relaxed their blockade of the French Atlantic ports. French and Spanish losses had been so severe in the campaign that it was believed by the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Barham, that the French Navy would be unable to respond in the following winter, and consequently withdrew most of the blockade fleet to Britain until the spring.[55] This strategy miscalculated the strength of the French Brest fleet, which had not been engaged in the Trafalgar campaign and therefore was at full strength. Taking advantage of the absence of the British squadrons off his principal Atlantic port, Napoleon ordered two squadrons to put to sea on 15 December 1805.[55] These forces were ordered to cruise the Atlantic shipping lanes in search of British merchant convoys and avoid confrontations with equivalent British forces. One squadron, under Vice-Admiral Corentin-Urbain Leissegues, was ordered to the Caribbean while the other, under Contre-Admiral Jean-Baptiste Willaumez, was ordered to the South Atlantic.[56]

Discovering on 24 December that the French squadrons had broken out of Brest, Barham despatched two squadrons in pursuit, led by Rear-Admiral Sir Richard Strachan and Rear-Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren.[57] A third squadron detached from the blockade of Cadiz without orders, under its commander Rear-Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth, all three British forces cruising the mid-Atlantic in search of the French. Following a brief encounter with Willaumez, Duckworth sailed to the Caribbean and there discovered and destroyed Leissegues' squadron at the Battle of San Domingo in February 1806.[58] With one of the French squadrons eliminated, Strachan and Warren remained in the mid-Atlantic anticipating Willaumez's return from his operations to the south. Warren's squadron was ordered to cruise in the Eastern Atlantic, in the region of the island of Madeira, directly across Linois's line of advance.[59]

Capture of Linois

At 03:00 on 13 March 1806, lookouts on Marengo spotted sails in the distance to the southeast. Ignoring arguments from Bruilhac that the sails could be a British battle squadron, Linois insisted that they were a merchant convoy and ordered his ships to advance.[60] The night was dark and visibility was consequently extremely limited; Linois was therefore unaware of the nature of his quarry until the 98-gun second rate HMS London loomed out of the night immediately ahead. London's captain, Sir Harry Burrard Neale, had sighted Linois's sails at a distance and sailed to investigate, hanging signals with blue lights that notified the rest of Warren's squadron, which was strung out ahead of the slow sailing London, of his intentions.[61] Neale's ship was accompanied by the frigate HMS Amazon under Captain William Parker, whose lookouts could not see the enemy but followed London's wake in anticipation of action.[54]

Linois made determined efforts to turn Marengo away from the large British ship, but his flagship was too slow and London opened up a fierce fire. Linois responded in kind and a battle commenced in which both ships suffered serve damage to their masts and rigging.[62] Belle Poule assisted Linois, but on the arrival of Amazon the French admiral gave orders for Bruilhac to escape. Turning to the northeast, Belle Poule pulled away with Amazon gaining rapidly. At 06:00, Linois tried to open some distance between Marengo and from her opponent, but found his flagship too badly damaged to manoeuvre, fire from London continuing unabated.[63] At 08:30, Parker reached Bruilhac's frigate and opened fire, inflicting serious damage to Belle Poule's rigging. By 10:25 it was clear that the French position was hopeless, with nearly 200 men killed or wounded, the latter including Linois and Vrignaud, both ships badly damaged and unmanoeuverable and the ships of the line HMS Foudroyant, HMS Repulse and HMS Ramillies all coming into range with three others close behind: recognising that defeat was inevitable, the most senior remaining officer on Marengo surrendered, Bruilhac following suit soon afterwards.[64]

Warren returned to Britain with his prizes, the squadron weathering a serious storm on 23 April which dismasted Marengo and Ramillies.[65] British losses in the engagement had totalled 14 dead and 27 wounded, to French casualties of 69 dead and 106 wounded. Warren was highly praised for his victory and both French ships were taken into British service under their French names.[66] The battle marked the end of Linois's cruise, three years and seven days after he had left Brest for the Indian Ocean. In contrast to the criticism attracted by his earlier engagements, Linois's final battle with Warren won praise for his resilience in the face of larger and more powerful opposition: British naval historian William James claimed that if Marengo and London had met independently, Linois might well have been the victor in the battle.[67]

Aftermath

Linois's operations in the Indian Ocean have been compared to those of Captain Karl von Müller in SMS Emden 108 years later: like von Müller, Linois's raids caused significant concern among British merchant houses and the British authorities in the Indian Ocean, in Linois's case principally due to the threat he posed to the East Indiaman convoys such as that encountered off Pulo Aura.[20] The practical effects of his raiding were however insignificant: in three years he took just five East Indiamen and a handful of country ships, briefly terrorising the Andhra coast in 1804 but otherwise failing to cause major economic disruption to British trade. The only achievement of his cruise was to force Rainier's squadron to operate in defence of British convoys and ports, preventing any offensive operations during Linois's time in the Indian Ocean.[68] The vast distances between friendly ports, the lack of sufficient food supplies or naval stores and the strength of British naval escorts after the initial months of war all played a part in Linois's failings to fully exploit his opportunity, but the blame for his inadequate achievements has been consistently placed with Linois's own personal leadership failings, both among his contemporaries and by historians. In battle Linois refused to place his ships in danger if it could be avoided, he spent considerable periods of the cruise refitting at French harbours and even when presented with an undefended target was reluctant to press his advantage.[62]

Linois and his men remained prisoners in Britain until the end of the war, Napoleon refusing to exchange them for British prisoners. His anger at Linois's failure would have precluded any further appointments even if he had returned to France, but in 1814 he was made Governor of Guadeloupe by King Louis XVIII. On the return of Napoleon during the Hundred Days, Linois declared for the Emperor, the only French colonial governor to do so. Within days a small British expeditionary force had ousted him and on 8 July Napoleon himself surrendered.[69] Linois's career was over, and he died in 1848 without performing any further military service. The Indian Ocean remained an active theatre of warfare for the next four years, the campaign against British merchant shipping in the region conducted by frigate squadrons operating from the Isle de France. These were initially led by Motard in Sémillante, who proved to be a more successful commerce raider than his former commander, until his ship was retired from service in 1808, too old and battered to remain in commission.[70] Command later passed to Commodore Jacques Hamelin, whose squadron caused more damage in one year than Linois managed in three: capturing seven East Indiamen during 1809–1810.[71] Eventually British forces were marshalled to capture the island in the Mauritius campaign of 1809–1811, culminating in the Invasion of Isle de France in December 1810 and the final defeat of the French in the Indian Ocean.[72]

Order of battle

| Admiral Linois's squadron | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes | |||||||

| Marengo | 74 | Contre-Admiral Charles-Alexandre Léon Durand Linois Captain Joseph-Marie Vrignaud |

Departed Brest on 3 March 1803, participated in all significant actions and was captured on 13 March 1806. | |||||||

| Belle Poule | 40 | Captain Alain-Adélaïde-Marie Bruilhac | Departed Brest on 3 March 1803, participated at Pulo Aura and the actions with Troubridge and Warren. Was captured on 13 March 1806. | |||||||

| Sémillante | 36 | Captain Léonard-Bernard Motard | Departed Brest on 3 March 1803, participated at Pulo Aura and Vizagapatam. Detached from Linois's squadron on 6 March 1805 for service in the Pacific, but returned to the Indian Ocean later in the year. Sold from French service in 1808. | |||||||

| Atalante | 40 | Captain Camille-Charles-Alexis Gaudin-Beauchène | Departed Brest on 3 March 1803, participated at Vizagapatam and was wrecked in September 1805 in Simon's Bay. | |||||||

| Berceau | 20 | Captain Emmanuel Halgan | Joined squadron at Isle de France in August 1803, participated at Pulo Aura and was ordered back to France in April 1804. | |||||||

| Aventurier | 16 | Lieutenant Harang | Joined squadron at Batavia in December 1803, participated at Pulo Aura before returning to the Dutch port in February 1804. Destroyed in the Raid on Batavia in November 1806.[73] | |||||||

| Source: James, Vol. 3, p. 176, Clowes, p. 58 | ||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Henderson, p. 47

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 102

- ↑ Adkins, p. 342

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 88

- ↑ Woodman, p. 150

- 1 2 Nelson Against Napoleon, Gardiner, p. 185

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 19

- 1 2 3 Rodger, p. 546

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 92

- ↑ The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 24

- ↑ Woodman, p. 172

- ↑ Woodman, p. 42

- ↑ Henderson, p. 19

- ↑ Woodman, p. 160

- ↑ James, Vol. 3, p. 176

- 1 2 James, Vol. 3, p. 211

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clowes, p. 59

- ↑ Clowes, p. 58

- 1 2 3 James, Vol. 3, p. 212

- 1 2 3 The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 26

- 1 2 James, Vol. 3, p. 213

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ↑ James, Vol. 3, p. 248

- ↑ Woodman, p. 194

- ↑ Clowes, p. 337

- ↑ James, Vol. 3, p. 249

- ↑ Clowes, p. 338

- ↑ Woodman, p. 195

- ↑ James, Vol. 3, p. 250

- ↑ Tracy, p. 114

- ↑ Clowes, p. 339

- ↑ The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 27

- 1 2 James, Vol. 3, p. 277.

- ↑ Clowes, p. 348

- 1 2 Rodger, p. 547

- 1 2 James, Vol. 3, p. 276

- 1 2 James, Vol. 3, p. 278

- ↑ Clowes, p. 349

- ↑ James, Vol. 3, p. 279

- ↑ Clowes, p. 350

- ↑ The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 29

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 150

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 153

- ↑ Clowes, p. 413

- 1 2 3 4 Clowes, p. 367

- 1 2 James, Vol. 4, p. 151

- ↑ Tracy, p. 287

- 1 2 Adkins, p. 184

- ↑ Tracy, p. 290

- 1 2 Adkins, p. 185

- 1 2 James, Vol. 4, p. 152

- 1 2 3 James, Vol. 4, p. 222

- 1 2 Adkins, p. 190

- 1 2 The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 17

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 185

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 186

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 201

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 28

- ↑ Clowes, p. 373

- ↑ Woodman, p. 215

- 1 2 Woodman, p. 216

- ↑ Adkins, p. 191

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 223

- ↑ The Victory of Seapower, Gardiner, p. 29

- ↑ Clowes, p. 374

- ↑ James, Vol. 4, p. 224

- ↑ The Campaign of Trafalgar, Gardiner, p. 19

- ↑ Marley, p. 376

- ↑ James, Vol. 5, p. 261

- ↑ Woodman, p. 283

- ↑ James, Vol. 5, p. 326

- ↑ "No. 16044". The London Gazette. 4 July 1807. p. 894.

References

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11916-3.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1998]. The Campaign of Trafalgar. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-358-3.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- Henderson CBE, James (1994) [1970]. The Frigates. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-432-6.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 3, 1800–1805. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 4, 1805–1807. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-908-5.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9411-8.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1998). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy; 200 Naval Heroes. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.