| Journalism |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

| Areas |

| Genres |

|

| Social impact |

| News media |

| Roles |

|

Advocacy journalism is a genre of journalism that adopts a non-objective viewpoint, usually for some social or political purpose.

Some advocacy journalists reject the idea that the traditional ideal of objectivity is possible or practical, in part due to the perceived influence of corporate sponsors in advertising. Proponents of advocacy journalism feel that the public interest is better served by a diversity of media outlets with varying points of view, or that advocacy journalism serves a similar role to that of muckraking.

Perspectives from advocacy journalists

In an April 2000 address to the Canadian Association of Journalists, Sue Careless gave the following commentary and advice to advocacy journalists, which seeks to establish a common view of what journalistic standards the genre should follow.[1]

- Acknowledge your perspective up front.

- Be truthful, accurate, and credible. Do not spread propaganda, do not take quotes or facts out of context, "don't fabricate or falsify", and "don't judge or suppress vital facts or present half-truths"

- Do not give your opponents equal time, but do not ignore them, either.

- Explore arguments that challenge your perspective, and report embarrassing facts that support the opposition. Ask critical questions of people who agree with you.

- Avoid slogans, ranting, and polemics. Instead, "articulate complex issues clearly and carefully."

- Be fair and thorough.

- Make use of neutral sources to establish facts.

Sue Careless also criticized the mainstream media for unbalanced and politically biased coverage, for economic conflicts of interest, and for neglecting certain public causes.[1] She said that alternative publications have advantages in independence, focus, and access, which make them more effective public-interest advocates than the mainstream media.[1]

History

United States

Nineteenth-century American newspapers were often partisan, publishing content that conveyed the opinions of journalists and editors alike.[2] These papers were often used to promote political ideologies and were partisan to certain parties or groups.

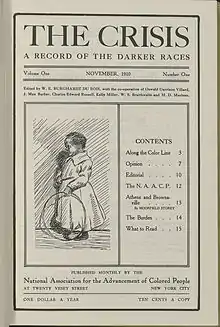

The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, was founded in 1910. It described itself as inheriting the tradition of advocacy journalism from Freedom's Journal,[3] which began in 1827 as "the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States".[4]

The Suffragist newspaper, founded in 1913 by the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, promoted the agenda of the National Woman's Party and was considered the only female political newspaper at the time.[5]

Muckrakers are often claimed as the professional ancestors of modern advocacy journalists; for example: Ida M. Tarbell, Ida B. Wells, Nellie Bly, Lincoln Steffens, Upton Sinclair, George Seldes, and I.F. Stone.

20th and 21st century advocacy journalists include:

- Oprah Winfrey, who used her talk show to give visibility to causes, groups, and people[6]

- Non-governmental organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union, Greenpeace, Human Rights Watch, and UNAIDS.[7]

- Trade journal reporters highlighting issues like the environment, safety, social responsibility, and diversity[8]

- Environmental journalism outlets like Inside Climate News and Yale Environment 360

- U.S. media outlets on the political left include Mother Jones, Jacobin, The Nation, and Pacifica Radio

- U.S. media outlets on the political right include The Daily Wire, National Review, and the One America News Network

Objectivity

Advocacy journalists may reject the principle of objectivity in their work for several different reasons.

Studies have shown that despite efforts to remain completely impartial, journalism is unable to escape some degree of implicit bias, whether political, personal, or metaphysical, whether intentional or subconscious. This does not necessarily indicate an outright rejection of the existence of an objective reality, but rather recognition of the inability to report on it in a value-free fashion and the controversial nature of objectivity in journalism. Many journalists and scholars accept the philosophical idea of pure "objectivity" as being impossible to achieve,[9] but still strive to minimize bias in their work. It is also argued that as objectivity is an impossible standard to satisfy, all types of journalism have some degree of advocacy, whether intentional or not.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Advocacy journalism" by Sue Careless. The Interim, May 2000. "Advocacy Journalism-Interim,May 2000". Archived from the original on 2005-04-29. Retrieved 2005-04-13. Rules and advice for advocacy journalists.

- ↑ "The Fall and Rise of Partisan Journalism". Center for Journalism Ethics, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin-Madison. 2011-04-20. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ Lewis, David Levering (July 1997). "Du Bois and the Challenge of the Black Press". www.thecrisismagazine.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ "Freedom's Journal, the First U.S. African-American Owned Newspaper | Wisconsin Historical Society". www.wisconsinhistory.org. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ "Suffragist Newspapers | National Woman's Party". nationalwomansparty.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ Advocacy Journalism and Precision Journalism

- ↑ Mathew Ingram (June 15, 2018). "Advocates are becoming journalists. Is that a good thing?". Columbia Journalism Review.

- ↑ Advocacy Journalism Part II: Who are we and what are we doing?

- ↑ Calcutt, Andrew; Hammond, Philip (2011-01-31). Journalism Studies: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781136831478.

- ↑ Fisher, Caroline (2016-08-01). "The advocacy continuum: Towards a theory of advocacy in journalism". Journalism. 17 (6): 711–726. doi:10.1177/1464884915582311. ISSN 1464-8849. S2CID 148210771.

Further reading

- Carberry, Belinda. "The Revolution in Journalism with an Emphasis on the 1960s and 1970s". www.yale.edu. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000. Retrieved 12 August 2020. Brief history of alternative journalistic forms, including references for further reading, designed for use by high school teachers.

- "Cornel West: The Uses of Advocacy Journalism". www.npr.org. The Tavis Smiley Show. 15 December 2004. Retrieved 12 August 2020. "Commentator Cornel West and NPR's Tavis Smiley discuss the notion of advocacy journalism in America, in the tradition of W. E. B. Du Bois, I. F. Stone and Ida B. Wells."