Kharga

الخارجة ϯⲟⲩⲁϩ ⲛ̀ϩⲏⲃ, ϯⲟⲩⲁϩ ⲙ̀ⲯⲟⲓ | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)   Clockwise from top: Temple of Hibis, qanat shaft near Qasr al-Labakha fortress, Deir al-Munira fortress, Umm al-Dabadib fortress | |

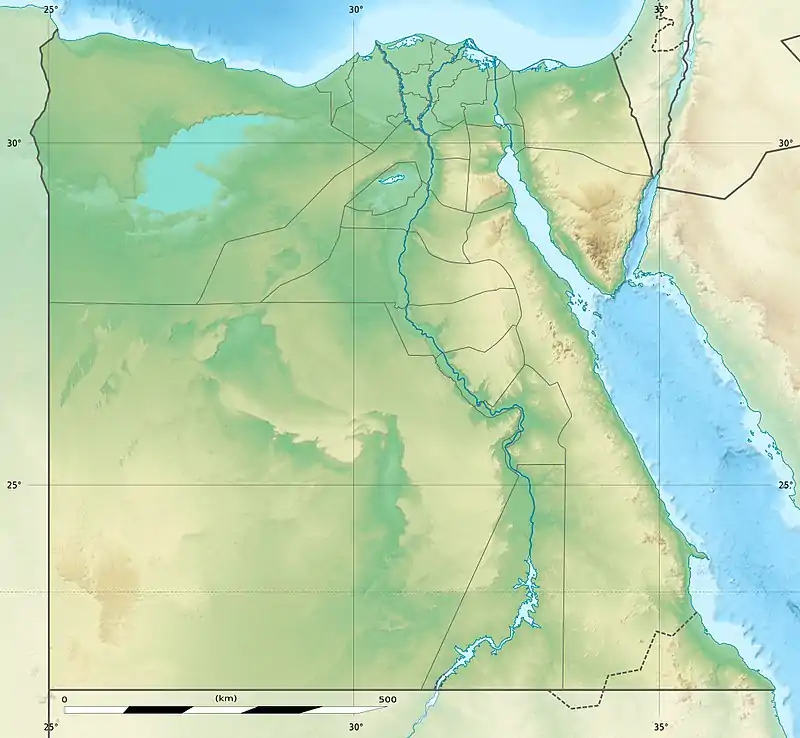

Kharga Location in Egypt | |

| Coordinates: 25°26′56″N 30°32′24″E / 25.44889°N 30.54000°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | New Valley |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,017 km2 (393 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

| • Total | 101,283 |

| • Density | 100/km2 (260/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

The Kharga Oasis (Arabic: الخارجة al-Ḫāriǧa, pronounced [elˈxæɾɡæ]) lit. 'the outer'; Coptic: (ϯ)ⲟⲩⲁϩ ⲛ̀ϩⲏⲃ (di)wah enhib, "Oasis of Hib", (ϯ)ⲟⲩⲁϩ ⲙ̀ⲯⲟⲓ (di)wah empsoi "Oasis of Psoi") is the southernmost of Egypt's five western oases. It is located in the Western Desert, about 200 km (125 miles) to the west of the Nile valley. "Kharga" or "El Kharga" is also the name of a major town located in the oasis, the capital of New Valley Governorate.[2] The oasis, which was known as the 'Southern Oasis' to the Ancient Egyptians, the 'outer' (he Esotero) to the Greeks[3] and Oasis Magna to the Romans, is the largest of the oases in the Libyan desert of Egypt. It is in a depression about 160 km (100 miles) long and from 20 km (12 miles) to 80 km (50 miles) wide.[4] Its population is 67,700 (2012).

Overview

| knm(t) "The Vineyard"[5] in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | |||||

| wḥꜣt rswt ḥb "The Southern Oasis of Hibis"[6] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kharga is the most modernised of Egypt's western oases. The main town is highly functional with all modern facilities, and virtually nothing left of old architecture. Although framed by the oasis, there is no oasis feeling to it, unlike all other oases in this part of Egypt. There is extensive thorn palm, acacia, buffalo thorn and jujube growth in the oasis surrounding the modern town of Kharga. Many remnant wildlife species inhabit this region.

Climate

The Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as hot desert (BWh).[7] Kharga Oasis experiences extreme summers for most of the year with no precipitation and warm winters with cool nights.

| Climate data for Kharga | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.0 (96.8) |

42.3 (108.1) |

47.5 (117.5) |

46.4 (115.5) |

49.8 (121.6) |

50.3 (122.5) |

47.5 (117.5) |

46.8 (116.2) |

45.4 (113.7) |

44.6 (112.3) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

50.3 (122.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

28.8 (83.8) |

34.5 (94.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.2 (104.4) |

39.9 (103.8) |

39.5 (103.1) |

37.1 (98.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

32.5 (90.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

0.8 (33.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 52 | 45 | 38 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 36 | 41 | 47 | 51 | 37.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 287.8 | 274.4 | 297.8 | 307.2 | 336.8 | 361.6 | 359.9 | 364.9 | 321.1 | 313.0 | 289.7 | 276.6 | 3,790.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate-Data.org[7] | |||||||||||||

Darb El Arba'īn caravan route

A trade route called Darb El Arba'īn ("the Way of Forty") passed through Kharga as part of a long caravan route running north–south between Middle Egypt and the Sudan. The ancient route connected the Al-Fashir area of Sudan to Asyut in Egypt, navigating through a chain of oases including Kharga, Selima Oasis and Bir Natrun.[9]

At least 700 years old,[9] it was likely used from as early as the Old Kingdom of Egypt for the transport and trade of gold, ivory, spices, wheat, animals and plants.[10]

The maximum extent of Darb El Arba'īn was northward from Kobbei in Darfur (located about 25 miles north of al-Fashir) passing through the desert, through Bir Natrum and Wadi Howar, and ending at the Nile River access point of Asyut in Egypt.[11] This is a journey of approximately 1,800 km (1,100 mi). The desert route was less expensive and safer than the more visually appealing Nile route.[12]

All the oases have always been crossroads of caravan routes converging from the barren desert. In the case of Kharga, this is made particularly evident by the presence of a chain of fortresses that the Romans built to protect the Darb El Arba'īn route. The forts vary in size and function, some being just small outposts, some guarding large settlements complete with cultivation. Some were installed where earlier settlements already existed, while others were probably started from scratch. All of them are made of mud bricks, but some also contain small stone temples with inscriptions on the walls.

Described by Herodotus as a road "traversed…in forty days," by his time the route had already become an important land route facilitating trade between Nubia and Egypt.[13] The length of the journey is the reason for it being called Darb El Arba`īn, the implication being "the forty-day road".[14]

After the prominent Christian theologian Nestorius was condemned as a heretic in the 431 Council of Ephesus, he was removed from his position as Patriarch of Constantinople and exiled to a monastery then located in the Great Oasis of Hibis (El Kharga). There he lived for the rest of his life. The monastery suffered attacks by desert bandits, and Nestorius was injured in one such raid. Nestorius seems to have survived there until at least 450 and there had composed the Bazaar of Heracleides—the only one of writings to survive in full, and of importance to the Christian Nestorians who follow his teachings.

As part of a caravan proceeding to Darfur, the English explorer W.G. Browne paused for several days at Kharga, leaving with the rest of the group 7 June 1793. At the time a gindi (a Turkish horseman, that performs extraordinary feats) was stationed at Kharga, "belonging to Ibrahim Bey El Kebir, to whom those villages appertain; and to [this official] is entrusted the management of what relates to the caravan during the time of its stay there."[15]

In 1930 the archaeologist, Gertrude Caton–Thompson, uncovered the palaeolithic history of Kharga.[16]

Temple of Hibis

Demographics

In his diary, “Al-Hajj Al-Bari” mentioned the most important families descending of Christians and Romans in the Kharga Oasis. They are the families of “Al-Jawiya, the families of Al-Tawayh, the Al-Bahramah family, the Al-Sanadiyah family, the Al-Azayza family, the Al-Badayrah family, the Al-Mahbasiya family, the Al-Hosnieh family, and the Al-Na’imah family And the Al-Sharayra family, and there are Nubian families in the village of Baris. There are few Berber families too who are thought to be the indigenous people of Kharga but the majority today are Arab families.

Perhaps the most important of these Arab families that came to the Khargha Oasis from the beginning of the year 300 AH are the families of the Idris from Tunisia or Libya, the family of Rekabia and the family of the jewehera from the Hijaz and the family of shakawera and the family of Al-Radawana and the family from the Arabs of Mecca and the family of Al-Shawami from the Levant and there are families from the countries of the Egyptian country such as Dabatiya and Asawiya from Assiut Or Sohag and the Awlad-el-sheikh from Egypt “It is more likely to mean Cairo”, the family of Njarin from Qalamoun in Dakhla, the family of Al Shaabna from Mallawi, the family of Al-Awamir from Al-Amayem tribe and the family of Al-Alawneh from Al-Alawiya in addition to Turkish families such as Al-Dabashiya, Al-Tarakah Al-Kharja and the Bash families The Qaqamqam, Askari, Tannabur, Qitas, and Kashif.

Transportation

A regular bus service connects the oasis to the other Western oases and to the rest of Egypt. In 1907, the narrow gauge Western Oasis Lines provided twice-weekly train services. A standard gauge railway line Kharga → Qena (Nile Valley) → Port Safaga (Red Sea) has been in service since 1996, but has been decommissioned soon after.

Archaeological sites

The Temple of Hibis is a Saite-era temple founded by Psamtik II, which was erected largely c. 500 BC. It is located about 2 kilometres north of modern Kharga, in a palm-grove.[17] There is a second 1st millennium BC temple in the southernmost part of the oasis at Dush.[18] An ancient Christian cemetery at El Bagawat also functioned at the Kharga Oasis from the 3rd to the 7th century AD. It is one of the earliest and best preserved Christian cemeteries in the ancient world.

The first list of sites is due to Ahmad Fakhri but serious archaeological work began in 1976 with Serge Sauneron, director of the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale.

- Sites

- Ain El Beleida (Roman)

- Ain El Labakha (Roman)

- Ain Manawir (Persian, Roman)

- Ain Shams El Din (Coptic church)

- Ain El Tarakwa (Roman)

- Ain Tauleib (Roman)

- Deir Mustafa Kashef (Coptic monastery)

- Deir El Munira (Roman)

- Gabbanat El Bagawat (Coptic cemetery)

- Gebel El Teir (Prehistoric times)

- El Nadura (Roman)

- Qasr El Dabashiya (Roman)

- Qasr Dush (Greco-Roman)

- Qasr El Ghuweita (Late Period)

- Qasr El Gibb (Roman)

- Qasr El Zayyan (Greco-Roman)

- Sumeira (Roman)

- Temple of Hibis (Persian - c. 6th century BC.)

- Umm El Dabadib (Roman)

- Umm Mawagir (Middle Kingdom, 2nd Intermediate Period)

Meteorite dagger

In June 2016, a report emerged that attributed the dagger buried with Pharaoh Tutankhamun to an iron meteorite, with similar proportions of metals (iron, nickel and cobalt) to one discovered near and named after Kharga Oasis. The dagger's metal was presumably from the same meteor shower. [19]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Al-Wāḥāt al-Khārijah (Kism (urban and rural parts), Egypt) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ↑ Ball, J. 1900. Kharga Oasis: its topography and geology. Survey Department, Public Works Ministry, Geological Survey Report 1899, Part II. Cairo: National Printing Department, 116 pp.

- ↑ Maciej Paprocki, Roads in the Deserts of Roman Egypt: Analysis, Atlas, Commentary (Oxbow, 2019), p. 259.

- ↑ Introduction to Kharga Oasis

- ↑ Gauthier, Henri (1928). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques. Vol. 5. p. 204.

- ↑ Gauthier, Henri (1925). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques. Vol. 1. p. 203.

- 1 2 "Climate: Kharga - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ↑ "Kharga Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 Stephens, Angela. "Saudi Aramco World : Riding the Forty Days' Road". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 16–27. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ Jobbins, Jenny (13–19 November 2003). "The 40 days' nightmare". Al-Ahram. Cairo, Egypt. Issue No. 664.

- ↑ Burr, J. Millard; Collins, Robert O. (2006). Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster. Princeton: Markus Wiener. pp. 6–7. ISBN 1-55876-405-4.

- ↑ Shaw, W. B. K. “DARB EL ARBA’IN. THE FORTY DAYS’ ROAD.” Sudan Notes and Records, vol. 12, no. 1, 1929, pp. 63–71. JSTOR, JSTOR 41719405. Accessed 27 Sep. 2022.

- ↑ Smith, Stuart Tyson. "Nubia: History". University of California Santa Barbara, Department of Anthropology. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- ↑ Richardson, Dan (1991). Egypt: the Rough Guide. Kent: Harrap Columbus. p. ii.

- ↑ Browne (1799). Travels in Africa, Egypt and Syria, from the years 1792 to 1798. London. p. 185. OCLC 25040149.

- ↑ Kirwan, L. P. (2004). "Thompson, Gertrude Caton (1888–1985)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Rev. ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Egyptian Monuments: Hibis". Retrieved 28 November 2008

- ↑ "New Persian temple found at Kharga" Egyptology News 22 February 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2008

- ↑ King Tutankhamun buried with dagger made of space iron, study finds, ABC News Online, 2 June 2016

Further reading

- Bliss, Frank (1998). Artisanat et artisanat d'art dans les oasis du désert occidental égyptien (in French). Köln: Frobenius-Institut.

- Bliss, Frank (1989). Wirtschaftlicher und sozialer Wandel im "Neuen Tal" Ägyptens. Über die Auswirkungen ägyptischer Regionalentwicklungspolitik in den Oasen der Westlichen Wüste (in German). Bonn.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). pp. 771–772.

- Dunand, Françoise; Ibrahim, Bahgat Ahmed; Hussein, Magdi (2008). Le matériel archéologique et les restes humains de la nécropole d'Aïn el-Labakha (oasis de Kharga) (in French). Cybèle. ISBN 978-2-915840-07-0.

External links

- 4CARE (Fourth-Century Christian Archaeological Record of Egypt) Database

- SKOS (South Kharga Oasis Survey) Database

- Colburn, Henry P. (2017). "KHARGA OASIS". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wilford, John Noble (6 September 2010) "Desert Roads Lead to Discovery in Egypt" The New York Times

- Information on the forts and archaeological work

- (in German) Khārga on Wikivoyage