| Pseudastacus Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

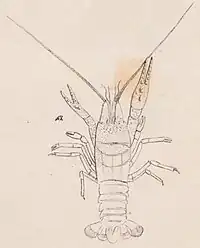

| Fossil of Pseudastacus pustulosus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Suborder: | Pleocyemata |

| Family: | †Stenochiridae |

| Genus: | †Pseudastacus Oppel, 1861 |

| Type species | |

| †Bolina pustulosa Münster, 1839 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

synonyms of Pseudastacus

synonyms of P. pustulosus

synonyms of P. mucronatus

| |

Pseudastacus (meaning "false Astacus", in comparison to the extant crayfish genus) is an extinct genus of decapod crustaceans that lived during the Jurassic period in Europe, and possibly the Cretaceous period in Lebanon. Many species have been assigned to it, though the placement of some species remain uncertain and others have been reassigned to different genera. The genus itself has been placed into different families by numerous authors, but is currently believed to be a member of Stenochiridae.

Members of this genus had a crayfish-like build, possessing long antennae and a frontmost pair of appendages enlarged into long and narrow pincers. Deep grooves are present on the carapace, which is around the same length as the abdomen. Sexual dimorphism is known in Pseudastacus, with the pincers of the females being more elongated than those of the males. There is evidence of possible gregarious behavior in the form of multiple individuals preserved alongside each other, possibly killed in a mass mortality event.

Discovery and naming

Fossils of Pseudastacus had been described prior to the naming of this genus, under other names which are currently invalid. In 1839, Georg zu Münster established the genus Bolina to include two species, B. pustulosa (the type species) and B. angusta, both of which are based on specimens collected from the Solnhofen Limestone. The generic name references the nymph Bolina from Greek mythology.[1] A year later, Münster described several fossils from the Solnhofen Limestone he believed to represent isopods, and erected the genus Alvis to contain the single species A. octopus, naming it after the dwarf Alvíss from Norse mythology.[2]

In 1861, Albert Oppel noted that the name Bolina was preoccupied by a genus of cnidarian, and thus the crustacean named by Münster had to be renamed. Oppel placed B. pustulosa and B. angusta into two new genera, Pseudastacus and Stenochirus respectively. Now renamed as Pseudastacus pustulosus and Stenochirus angustus, the two species became the type species of their own respective genera. The name Pseudastacus means "false Astacus", referencing its resemblance to the modern crayfish genus.[3]

Description

Pseudastacus is a small invertebrate, with the carapace of P. lemovices reaching a length of 11 mm (0.43 in) (excluding the rostrum) and a height of 6.5 mm (0.26 in).[4] The known specimens of P. pustulosus range from 4–6 cm (1.6–2.4 in) in total length.[5]

Members of this genus often have an uneven carapace surface, with some species (such as P. pustulosus) having tubercles and others (such as P. lemovices) having pits distributed uniformly across the carapace surface. Individuals with smoother carapaces are also documented, though this may be due to abrasion. Grooves are present on the carapace, including a deep, arch-shaped cervical groove that stretches across the top and sides of the carapace, and an additional groove behind it on either side. The rostrum is triangular and elongated, with three lateral spines.[4][5] The carapace and head are separated by an arch-shaped incision. A pair of long antennae and two pairs of shorter antennules extend from the head, with the outer antennules being slightly narrower and more pointed than the outer pair.[2] A pair of compound eyes are attached to the head by short eye stalks.[5]

The first three pairs of appendages terminate with chelae (pincers), and the appendages furthest front are particularly long and enlarged. The abdomen is around the length of the carapace, with the frontmost segment being the smallest. The pereiopods (walking legs) on the thorax decrease in size the further back they are placed, the pair furthest front being largest and longest. The uropods are equal in length, with a ridge down the middle and long setae on the margins.[4]

Classification

In the centuries since it was first discovered, Pseudastacus has been placed in a wide variety of families by many different authors. For many decades, the genus was thought to be a member of Nephropidae (the lobster family), as first reported by Victor van Straelen in 1925.[6] This placement was followed by subsequent authors such as Beurlen (1928), Glaessner (1929), and Chong & Förster (1976).[7][8][9] In 1983, Henning Albrecht erected the family Protastacidae and moved Pseudastacus into it, whereas Tshudy & Babcock (1997) included the genus into their newly-established family Chilenophoberidae.[10][11] Although Garassino & Schweigert (2006) continued to place Pseudastacus in Proastacidae following Albrecht (1983), other authors in the 2000s would place it in Chilenophoberidae based on the more recent findings of Tshudy & Babcock (1997).[5][12][13]

In 2013, Karasawa et al. recovered Pseudastacus as the sister taxon to Stenochirus, making Chilenophoberidae a paraphyletic group. The family was therefore synonymized with Stenochiridae. The following cladogram shows the placement of Pseudastacus within Stenochiridae according to the study:[14]

| Stenochiridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Species

Several species have been assigned to the genus Pseudastacus, though the placement of some species remains uncertain or tentative.

- P. pustulosus is the type species of the genus, first named as Bolina pustulosa by Münster in 1839 and moved to Pseudastacus in 1861. Its fossils were found in the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany, which date back to the Tithonian stage of the late Jurassic period.[1][3]

- P. mucronatus was originally named as Astacus mucronatus by John Phillips in 1835. The type specimen was extracted from the Speeton Clay Formation in Yorkshire, England, and is a fragment of the pincer. The chela is very large, with alternating large and small tubercles on the inner margins.[15] This is unlike the narrower and longer pincers of other Pseudastacus species, and the specimen may be referrable to Hoploparia dentata.[16]

- P. minor was described by Oscar Fraas in 1878 from a specimen found in Cenomanian-aged deposits in Lebanon.[17] This specimen is now lost and only the original illustration remains, which shows features unlike any other Pseudastacus species: the rostrum is extremely long, there is an additional abdomen segment, the clawed limbs are placed further back and the general pincer shape is different. Its placement in this genus is thus uncertain.[4]

- P. pusillus is based on a fossil from the Bajocian-aged deposits of May-sur-Orne, France described in 1925 by Victor van Straelen.[6] The fossil was destroyed in World War II and it is difficult to tell from the original line drawing of the specimen whether this species truly belongs to Pseudastacus.[4]

- P. lemovices was named in 2020 based on five specimens preserved in a slab of Sinemurian-aged limestone, collected from Chauffour-sur-Vell, France. The specific name honors the Lemovices, a Gallic tribe that lived near this locality. It is the oldest known species of the family Stenochiridae.[4]

Reassigned species

The following species were formerly placed in Pseudastacus, but have now been moved to different genera.

- P. hakelensis was first named as Homarus hakelensis in 1878. The species lived during the Cenomanian stage in Lebanon.[17] It was moved to Notahomarus in 2017.[18]

- P. dubertreti, described in 1946 from a fossil kept in the National Museum of Natural History, France, lived in Lebanon during the Cenomanian stage.[19] Later study of the fossil found this species to be synonymous with Carpopenaeus callirostris in 2006.[5]

- P. llopisi was named in 1971 and is known from numerous specimens found in the early Cretaceous-aged site of Las Hoyas, Spain.[20] In 1997 it was reassigned to the genus Austropotamobius.[21]

Palaeobiology

Sexual dimorphism

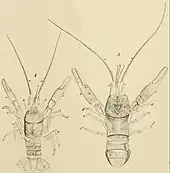

Albert Oppel noticed that Pseudastacus fossils from the Solnhofen Limestone could be distinguished into two morphs; aside from those most similar to the P. pustulosus type specimen, there were also some with smaller bodies and longer, more slender claws. Oppel believed the latter morph to be a separate species which in 1862 he named P. muensteri.[22] Over a century later, Garassino and Guenter (2006) found that specimens of P. muensteri were essentially identical to P. pustulosus aside from the claw form. In addition, they noted that in fossil glypheids and the extant Neoglyphea inopinata, the females longer clawed limbs than the males. Based on this, they declared P. muensteri as a junior synonym of P. pustulosus, actually representing female specimens of the species.[5]

Social behavior

The type series of P. lemovices is made up of five individuals preserved together in a single limestone slab, possibly indicating the species exhibited gregarious behaviour, with this group being killed in a mass mortality event (perhaps caused by temperature changes or lack of oxygen).[4] Evidence of gregarious behaviour is also known in other fossil lobsters, as well as in extant species.[23][24]

References

- 1 2 Münster, Georg Herbert (1839). Beitraege zur Petrefacten-Kunde : mit XXX. nach der Natur gezeichneten tafeln (in German). Bayreuth: in Commission der Buchner'schen Buchhandlung. Archived from the original on 2023-11-23. Retrieved 2023-11-23.

- 1 2 Münster, G (1840). "Ueber einige Isopoden in den Kalkschiefern von Bayern" (PDF). Beiträge zur Petrefactenkunde (in German). 3: 19–23. Archived from the original on 2023-11-18. Retrieved 2023-11-23.

- 1 2 A, Oppel (1861). "Die Arten der Gattungen Eryma, Pseudastacus, Magila und Etallonia" (PDF). Jahreshefte des Vereins fur Vaterlandische Naturkunde in Wurttemberg (in German). 17: 355–364. Archived from the original on 2023-11-23. Retrieved 2023-11-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Charbonnier, Sylvain; Audo, Denis (March 2020). "A new stenochirid lobster (Crustacea, Decapoda, Stenochiridae) from the Early Jurassic of France". Geodiversitas. 42 (7): 93–102. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2020v42a7. ISSN 1280-9659.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Garassino, Alessandro; Schweigert, Guenter (January 2006). "The Upper Jurassic Solnhofen decapod crustacean fauna: Review of the types from old descriptions. Part I. Infraorders Astacidea, Thalassinidea, and Palinura" (PDF). Memorie della Società italiana di Scienze naturali e del Museo civico di Storia naturale di Milano. 34 (1): 1–64. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- 1 2 Van Straelen, V. (1925). "Contribution à l'étude des Crustacés Décapodes de la période jurassique". Mémoires de la Classe des Sciences de l'Académie royale de Belgique. 7: 1–462. Archived from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Beurlen, Karl (1928-01-01). "Die Decapoden des Schwäbischen Jura, mit Ausnahme der aus den oberjurassischen Plattenkalken stammenden. Beiträge zur Systematik und Stammesgeschichte der Decapoden". Palaeontographica (1846-1933) (in German): 115–278. Archived from the original on 2023-08-26. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Fossilium catalogus: Animalia / ed. a J. F. Pompeckj. Crustacea decapoda / M. F. Glaessner (in German). W. Junk. 1929.

- ↑ Chong, G; Förster, R (1976). "Chilenophoberus atacamensis, a new decapod crustacean from the Middle Oxfordian of the Cordillera de Domeyko, northern Chile". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 3: 145–156. Archived from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Albrecht, Henning (1983-01-26). "Die Protastacidae n. fam., fossile Vorfahren der Flußkrebse?" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Monatshefte (in German): 5–15. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1983/1983/5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Tshudy, D; Babcock, L.E. (1997-01-01). "Morphology-based phylogenetic analysis of the clawed lobsters (family Nephropidae and the new family Chilenophoberidae)". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 17 (2): 253–263. doi:10.1163/193724097x00288. ISSN 0278-0372.

- ↑ De Grave, Sammy; Pentcheff, N. Dean; Ahyong, Shane T.; Chan, Tin-Yam; Crandall, Keith A.; Dworschak, Peter C.; Felder, Darryl L.; Feldmann, Rodney M.; Fransen, Charles H. J. M.; Goulding, Laura Y. D.; Lemaitre, Rafael; Low, Martyn E. Y.; Martin, Joel W.; Ng, Peter K. L.; Schweitzer, Carrie E. (2009). "A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans". The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology: 1–109. hdl:10088/8358. ISSN 0217-2445.

- ↑ Schweitzer, Carrie; Feldmann, Rodney; Garassino, Alessandro; Karasawa, Hiroaki; Schweigert, Günter (2010-01-07). "Systematic List of Fossil Decapod Crustacean Species". Crustaceana Monographs. 10: 1–222. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004178915.i-222. ISBN 978-90-474-4126-7. S2CID 83766569.

- ↑ Karasawa, Hiroaki; Schweitzer, Carrie E.; Feldmann, Rodney M. (2013-01-01). "Phylogeny and systematics of extant and extinct lobsters". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 33 (1): 78–123. doi:10.1163/1937240X-00002111. ISSN 0278-0372.

- ↑ Phillips, John; Phillips, John (1835). Illustrations of the geology of Yorkshire, or, A description of the strata and organic remains: accompanied by a geological map, sections and plates of the fossil plants and animals (2nd ed. of part. 1. ed.). London: pr. for J. Murray. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.127948. Archived from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Woods, Henry (December 1925). "A Monograph of the Fossil Macrurous Crustacea of England. Part II. Pages 17–40; Plates V–VIII". Monographs of the Palaeontographical Society. 77 (359): 17–40. Bibcode:1925MPalS..77...17W. doi:10.1080/02693445.1925.12035594. ISSN 0269-3445.

- 1 2 Fraas, Oscar (1878). Geologisches aus dem Libanon (in German). Schweizerbart.

- ↑ Charbonnier, Sylvain; Audo, Denis; Garassino, Alessandro; Hyžný, Matús, eds. (2017). Fossil crustacea of Lebanon. Mémoires du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum. ISBN 978-2-85653-785-5.

- ↑ Jean, Roger (1946). Les invertébrés des couches a poissons du crétacé supérieur du Liban : étude paléobiologique des gesements (in French). Paris: Société géologique de France. Archived from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Via, Luis (1971). "Crustáceos decápodos del Jurásico Superior de Montsech (Lérida)". Cuadernas Geología Ibérica. 2: 607–612. hdl:10261/6397.

- ↑ Garassino, Alessandro (1997). "The macruran decapod crustaceans of the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Barremian) of Las Hoyas (Cuenca, Spain)". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milano. 137 (1–2): 101–126. Archived from the original on 2023-11-24. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ↑ Oppel, Carl Albert; Zittel, Karl Alfred von; Boehm, Georg; Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (1862). "Über jurassische Crustaceen". Palaeontologische Mittheilungen aus dem Museum des koenigl. bayer. Staates. Smithsonian Libraries. Stuttgart : Ebner & Seubert.

- ↑ Klompmaker, Adiël A.; Fraaije, René H. B. (2012-03-07). "Animal Behavior Frozen in Time: Gregarious Behavior of Early Jurassic Lobsters within an Ammonoid Body Chamber". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e31893. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731893K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031893. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3296704. PMID 22412846.

- ↑ Zimmer-Faust, Richard K.; Spanier, Ehud (1987-02-17). "Gregariousness and sociality in spiny lobsters: implications for den habitation". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 105 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(87)80029-1. ISSN 0022-0981.

External links

Media related to Pseudastacus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pseudastacus at Wikimedia Commons