អង្គរវត្ត | |

Front side of the main complex | |

Location in Cambodia | |

| Location | Siem Reap, Cambodia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″E / 13.41250°N 103.86667°E |

| Altitude | 65 m (213 ft) |

| History | |

| Builder | Started by Suryavarman II Completed by Jayavarman VII |

| Founded | 12th century[1] |

| Cultures | Khmer Empire |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Khmer (Angkor Wat style) |

| Official name | Angkor |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1992 (16th session) |

| Reference no. | 668 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

Angkor Wat (/ˌæŋkɔːr ˈwɒt/; Khmer: អង្គរវត្ត, "City/Capital of Temples") is a temple complex in Cambodia, located on a site measuring 162.6 hectares (1,626,000 m2; 402 acres). It resides within the ancient Khmer capital city of Angkor. The Guinness World Records considers it as the largest religious structure in the world.[2] Originally constructed as a Hindu temple dedicated to the god Vishnu for the Khmer Empire by King Suryavarman II during the 12th century, it was gradually transformed into a Buddhist temple towards the end of the century; as such, it is also described as a "Hindu-Buddhist" temple.[3][4]

Angkor Wat was built at the behest of the Khmer King Suryavarman II[5] in the early 12th century in Yaśodharapura (Khmer: យសោធរបុរៈ, present-day Angkor), the capital of the Khmer Empire, as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. Angkor Wat combines two basic plans of Khmer temple architecture: the temple-mountain and the later galleried temple. It is designed to represent Mount Meru, home of the devas in Hindu mythology: within a moat more than 5 kilometres (3 mi) long[6] and an outer wall 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) long are three rectangular galleries, each raised above the next. At the centre of the temple stands a quincunx of towers. Unlike most Angkorian temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the west; scholars are divided as to the significance of this. The temple is admired for the grandeur and harmony of the architecture, its extensive bas-reliefs, and for the numerous devatas adorning its walls. The modern name Angkor Wat, alternatively Nokor Wat,[7] means "Temple City" or "City of Temples" in Khmer. Angkor (អង្គរ ângkôr), meaning "city" or "capital city", is a vernacular form of the word nokor (នគរ nôkôr), which comes from the Sanskrit/Pali word nagara (Devanāgarī: नगर).[8] Wat (វត្ត vôtt) is the word for "temple grounds", also derived from Sanskrit/Pali vāṭa (Devanāgarī: वाट), meaning "enclosure".[9]

The original name of the temple was Vrah Viṣṇuloka or Parama Viṣṇuloka meaning "the sacred dwelling of Vishnu".[10][11]

History

Angkor Wat lies 5.5 kilometres (3+1⁄2 mi) north of the modern town of Siem Reap, and a short distance south and slightly east of the previous capital, which was centred at Baphuon. In an area of Cambodia where there is an essential group of ancient structures, it is the southernmost of Angkor's main sites.

The construction of Angkor Wat took place over 28 years from 1122 to 1150 CE during the reign of King Suryavarman II (ruled 1113–c. 1150).[12] A brahmin by the name of Divākarapaṇḍita (1040–c. 1120) was responsible for urging Suryavarman II to construct the temple.[13] All of the original religious motifs at Angkor Wat derived from Hinduism.[14] Breaking from the Shaiva tradition of previous kings, Angkor Wat was instead dedicated to Vishnu. It was built as the king's state temple and capital city. As neither the foundation stela nor any contemporary inscriptions referring to the temple have been found, its original name is unknown, but it may have been known as Vrah Viṣṇuloka after the presiding deity. Work seems to have ended shortly after the king's death, leaving some of the bas-relief decoration unfinished.[15] The term Vrah Viṣṇuloka or Parama Viṣṇuloka literally means "The king who has gone to the supreme world of Vishnu", which refer to Suryavarman II posthumously and intend to venerate his glory and memory.[10]

In 1177, approximately 27 years after the death of Suryavarman II, Angkor was sacked by the Chams, the traditional enemies of the Khmer.[16] Thereafter the empire was restored by a new king, Jayavarman VII, who established a new capital and state temple (Angkor Thom and the Bayon, respectively), a few kilometers north, dedicated to Buddhism, because the king's new wife, Indratevi, a devout Mahayana Buddhist, encouraged him to convert. Angkor Wat was therefore also gradually converted into a Buddhist site, and many Hindu sculptures were replaced by Buddhist art.[14]

Towards the end of the 12th century, Angkor Wat gradually transformed from a Hindu centre of worship to Buddhism, which continues to the present day.[4] Angkor Wat is unusual among the Angkor temples in that although it was largely neglected after the 16th century, it was never completely abandoned.[17] Fourteen inscriptions dated from the 17th century, discovered in the Angkor area, testify to Japanese Buddhist pilgrims that had established small settlements alongside Khmer locals.[18] At that time, the temple was thought by the Japanese visitors to be the famed Jetavana garden of the Buddha, which was originally located in the kingdom of Magadha, India.[19] The best-known inscription tells of Ukondayu Kazufusa, who celebrated the Khmer New Year at Angkor Wat in 1632.[20]

The first Western visitor to the temple was António da Madalena, a Portuguese[21] friar who visited in 1586 and said that it "is of such extraordinary construction that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly since it is like no other building in the world. It has towers and decoration and all the refinements which the human genius can conceive of."[22]

In 1622, The Poem of Angkor Wat composed in Khmer verse describes the beauty of Angkor Wat and creates a legend around the construction of the complex, supposedly a divine castle built for legendary Khmer king Preah Ket Mealea by Hindu god Preah Pisnukar (or Braḥ Bisṇukār, Vishvakarman), as Suryavarman II had already vanished from people's minds.[23]

In 1860, with the help of French missionary Father Charles-Émile Bouillevaux, the temple was effectively rediscovered by the French naturalist and explorer Henri Mouhot, who popularised the site in the West through the publication of travel notes, in which he wrote:

One of these temples, a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michelangelo, might take an honorable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged.[24]

In 1861 German anthropologist Adolf Bastian undertook a four-year trip to Southeast Asia. His account of this trip, The People of East Asia, ran to six volumes. When Bastian finally published the studies and observations during his Journey through Cambodia to Cochinchina in Germany in 1868 – told in detail but uninspiredly, above all without a single one of his drawings of the Angkorian sites – this work hardly made an impression, while everyone was talking about Henri Mouhot's posthumous work with vivid descriptions of Angkor, Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China, Siam, Cambodia and Laos, published in 1864 through the Royal Geographical Society.[25]

There were no ordinary dwellings or houses or other signs of settlement, including cooking utensils, weapons, or items of clothing usually found at ancient sites.[26]

The artistic legacy of Angkor Wat and other Khmer monuments in the Angkor region led directly to France adopting Cambodia as a protectorate on 11 August 1863 and invading Siam to take control of the ruins. This quickly led to Cambodia reclaiming lands in the northwestern corner of the country such as the areas of Siem Reap, Battambang, and Sisophon which were under Siamese rule from 1795 to 1907.[27][28]

Angkor Wat's aesthetics were on display in the plaster cast museum of Louis Delaporte called musée Indo-chinois which existed in the Parisian Trocadero Palace from c.1880 to the mid-1920s.[29]

The 20th century saw a considerable restoration of Angkor Wat.[30] Gradually teams of laborers and archeologists pushed back the jungle and exposed the expanses of stone, permitting the sun to once again illuminate the dark corners of the temple. Angkor Wat caught the attention and imagination of a wider audience in Europe when the pavilion of French protectorate of Cambodia, as part of French Indochina, recreated the life-size replica of Angkor Wat during Paris Colonial Exposition in 1931.[31]

Cambodia gained independence from France on 9 November 1953 and has controlled Angkor Wat since then. From the colonial period onwards, until the site was nominated a UNESCO World Heritage in 1992, the temple of Angkor Wat was instrumental in the formation of the modern and gradually globalised concept of built cultural heritage.[32]

Restoration work was interrupted by the Cambodian Civil War and Khmer Rouge control of the country during the 1970s and 1980s, but relatively little damage was done during this period. Camping Khmer Rouge forces used whatever wood remained in the building structures for firewood, and a shoot-out between Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese forces put a few bullet holes in a basrelief. Far more damage was done after the wars, by art thieves working out of Thailand, which, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, claimed almost every head that could be lopped off the structures, including reconstructions.[33]

The temple is a symbol of Cambodia and is a source of national pride that has factored into Cambodia's diplomatic relations with France, the United States, and its neighbour Thailand. A depiction of Angkor Wat has been a part of Cambodian national flags since the introduction of the first version circa 1863.[34] From a larger historical and transcultural perspective, however, the temple of Angkor Wat did not become a symbol of national pride sui generis but had been inscribed into a larger politico-cultural process of French-colonial heritage production in which the original temple site was presented in French colonial and universal exhibitions in Paris and Marseille between 1889 and 1937.[35]

In December 2015, it was announced that a research team from the University of Sydney had found a previously unseen ensemble of buried towers built and demolished during the construction of Angkor Wat, as well as a massive structure of unknown purpose on its south side and wooden fortifications. The findings include evidence of low-density residential occupation in the region, with a road grid, ponds, and mounds. These indicate that the temple precinct, bounded by a moat and wall, may not have been used exclusively by the priestly elite, as was previously thought. The team used LiDAR, ground-penetrating radar and targeted excavation to map Angkor Wat.[36]

According to a myth, the construction of Angkor Wat was ordered by Indra to serve as a palace for his son Precha Ket Mealea.[37] According to the 13th-century Chinese traveller Zhou Daguan, some believed that the temple was constructed in a single night by a divine architect.[38]

Architecture

Site and plan

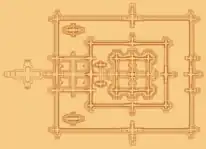

Angkor Wat is a unique combination of the temple mountain (the standard design for the empire's state temples) and the later plan of concentric galleries, most of which were originally derived from religious beliefs of Hinduism.[14] The construction of Angkor Wat suggests that there was a celestial significance with certain features of the temple. This is observed in the temple's east–west orientation, and lines of sight from terraces within the temple that show specific towers to be at the precise location of the solstice at sunrise.[39] The temple is a representation of Mount Meru, the home of the gods according to Hindu mythology: the central quincunx of towers symbolise the five peaks of the mountain, and the walls and moat symbolise the surrounding mountain ranges and ocean.[40] Access to the upper areas of the temple was progressively more exclusive, with the laity being admitted only to the lowest level.[41]

The Angkor Wat temple's main tower aligns with the morning sun of the spring equinox.[42][43] Unlike most Khmer temples, Angkor Wat is oriented to the west rather than the east. This has led many (including Maurice Glaize and George Coedès) to conclude that Suryavarman intended it to serve as his funerary temple.[44][45] Further evidence for this view is provided by the bas-reliefs, which proceed in a counter-clockwise direction—prasavya in Hindu terminology—as this is the reverse of the normal order. Rituals take place in reverse order during Brahminic funeral services.[30]

Archaeologist Charles Higham also describes a container that may have been a funerary jar that was recovered from the central tower.[46] It has been nominated by some as the greatest expenditure of energy on the disposal of a corpse.[47] Freeman and Jacques, however, note that several other temples of Angkor depart from the typical eastern orientation, and suggest that Angkor Wat's alignment was due to its dedication to Vishnu, who was associated with the west.[40]

Drawing on the temple's alignment and dimensions, and on the content and arrangement of the bas-reliefs, researcher Eleanor Mannikka argues that the structure represents a claimed new era of peace under King Suryavarman II: "as the measurements of solar and lunar time cycles were built into the sacred space of Angkor Wat, this divine mandate to rule was anchored to consecrated chambers and corridors meant to perpetuate the king's power and to honour and placate the deities manifest in the heavens above."[48][49] Mannikka's suggestions have been received with a mixture of interest and scepticism in academic circles.[46] She distances herself from the speculations of others, such as Graham Hancock, that Angkor Wat is part of a representation of the constellation Draco.[50]

The oldest surviving plan of Angkor Wat dates to 1715 and is credited to Fujiwara Tadayoshi. The plan is stored in the Suifu Meitoku-kai Shokokan Museum in Mito, Japan.[51]

Style

.jpg.webp)

Angkor Wat is the prime example of the classical style of Khmer architecture—the Angkor Wat style—to which it has given its name. By the 12th century, Khmer architects had become skilled and confident in the use of sandstone (rather than brick or laterite) as the main building material. Most of the visible areas are sandstone blocks, while laterite was used for the outer wall and hidden structural parts. The binding agent used to join the blocks is yet to be identified, although natural resins or slaked lime has been suggested.[52]

The temple has drawn praise above all for the harmony of its design. According to Maurice Glaize, a mid-20th-century conservator of Angkor, the temple "attains a classic perfection by the restrained monumentality of its finely balanced elements and the precise arrangement of its proportions. It is a work of power, unity, and style."[53]

.jpg.webp)

Architecturally, the elements characteristic of the style include the ogival, redented towers shaped like lotus buds; half-galleries to broaden passageways; axial galleries connecting enclosures; and the cruciform terraces which appear along the main axis of the temple. Typical decorative elements are devatas (or apsaras), bas-reliefs, pediments, extensive garlands and narrative scenes. The statuary of Angkor Wat is considered conservative, being more static and less graceful than earlier work.[54] Other elements of the design have been destroyed by looting and the passage of time, including gilded stucco on the towers, gilding on some figures on the bas-reliefs, and wooden ceiling panels and doors.[55]

Architect Jacques Dumarçay believes the layout of Angkor Wat borrows Chinese influence in its system of galleries which join at right angles to form courtyards. However, the axial pattern embedded in the plan of Angkor Wat may be derived from Southeast Asian cosmology in combination with the mandala represented by the main temple.[12]

Features

Outer enclosure

The outer wall, 1,024 m (3,360 ft) by 802 m (2,631 ft) and 4.5 m (15 ft) high, is surrounded by a 30 m (98 ft) apron of open ground and a moat 190 m (620 ft) wide and over 5 kilometres (3 mi) in perimeter.[6] The moat extends 1.5 kilometres from east to west and 1.3 kilometres from north to south.[57] Access to the temple is by an earth bank to the east and a sandstone causeway to the west; the latter, the main entrance, is a later addition, possibly replacing a wooden bridge.[58] There are gopuras at each of the cardinal points; the western is by far the largest and has three ruined towers. Glaize notes that this gopura both hides and echoes the form of the temple proper.[59]

Under the southern tower is a statue known as Ta Reach, originally an eight-armed statue of Vishnu that may have occupied the temple's central shrine.[58] Galleries run between the towers and as far as two further entrances on either side of the gopura often referred to as "elephant gates", as they are large enough to admit those animals. These galleries have square pillars on the outer (west) side and a closed wall on the inner (east) side. The ceiling between the pillars is decorated with lotus rosettes; the west face of the wall with dancing figures; and the east face of the wall with balustered windows, dancing male figures on prancing animals, and devatas, including (south of the entrance) the only one in the temple to be showing her teeth.

The outer wall encloses a space of 820,000 square metres (203 acres), which besides the temple proper was originally occupied by the city and, to the north of the temple, the royal palace. Like all secular buildings of Angkor, these were built of perishable materials rather than of stone, so nothing remains of them except the outlines of some of the streets.[60] Most of the area is now covered by forest. A 350 m (1,150 ft) causeway connects the western gopura to the temple proper, with naga balustrades and six sets of steps leading down to the city on either side. Each side also features a library with entrances at each cardinal point, in front of the third set of stairs from the entrance, and a pond between the library and the temple itself. The ponds are later additions to the design, as is the cruciform terrace guarded by lions connecting the causeway to the central structure.[60]

Central structure

The temple stands on a terrace raised higher than the city. It is made of three rectangular galleries rising to a central tower, each level higher than the last. The two inner galleries each have four large towers at their ordinal corners (that is, NW, NE, SE, and SW) surrounding a higher fifth tower. This pattern is sometimes called a quincunx and represents the mountains of Meru. Because the temple faces west, the features are set back towards the east, leaving more space to be filled in each enclosure and gallery on the west side; for the same reason, the west-facing steps are shallower than those on the other sides.

Mannikka interprets the galleries as being dedicated to the king, Brahma, the moon, and Vishnu.[15] Each gallery has a gopura at each of the points. The outer gallery measures 187 m (614 ft) by 215 m (705 ft), with pavilions rather than towers at the corners. The gallery is open to the outside of the temple, with columned half-galleries extending and buttressing the structure. Connecting the outer gallery to the second enclosure on the west side is a cruciform cloister called Preah Poan (meaning "The Thousand Buddhas" Gallery).[11] Buddha images were left in the cloister by pilgrims over the centuries, although most have now been removed. This area has many inscriptions relating to the good deeds of pilgrims, most written in Khmer but others in Burmese and Japanese. The four small courtyards marked out by the cloister may originally have been filled with water.[61] North and south of the cloister are libraries.

Beyond, the second and inner galleries are connected to two flanking libraries by another cruciform terrace, again a later addition. From the second level upwards, devatas abound on the walls, singly or in groups of up to four. The second-level enclosure is 100 m (330 ft) by 115 m (377 ft), and may originally have been flooded to represent the ocean around Mount Meru.[62] Three sets of steps on each side lead up to the corner towers and gopuras of the inner gallery. The steep stairways may represent the difficulty of ascending to the kingdom of the gods.[63] This inner gallery, called the Bakan, is a 60 m (200 ft) square with axial galleries connecting each gopura with the central shrine and subsidiary shrines located below the corner towers.

The roofings of the galleries are decorated with the motif of the body of a snake ending in the heads of lions or garudas. Carved lintels and pediments decorate the entrances to the galleries and the shrines. The tower above the central shrine rises 43 m (141 ft) to a height of 65 m (213 ft) above the ground; unlike those of previous temple mountains, the central tower is raised above the surrounding four.[64] The shrine itself, originally occupied by a statue of Vishnu and open on each side, was walled in when the temple was converted to Theravada Buddhism, the new walls featuring standing Buddhas. In 1934, the conservator George Trouvé excavated the pit beneath the central shrine: filled with sand and water it had already been robbed of its treasure, but he did find a sacred foundation deposit of gold leaf two metres above ground level.[65]

Decoration

Integrated with the architecture of the building, one of the causes for its fame is Angkor Wat's extensive decoration, which predominantly takes the form of bas-relief friezes. The inner walls of the outer gallery bear a series of large-scale scenes mainly depicting episodes from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Higham has called these "the greatest known linear arrangement of stone carving".[66] From the north-west corner anti-clockwise, the western gallery shows the Battle of Lanka (from the Ramayana, in which Rama defeats Ravana) and the Battle of Kurukshetra (from the Mahabharata, showing the mutual annihilation of the Kaurava and Pandava clans). On the southern gallery follow the only historical scene, a procession of Suryavarman II, then the 32 hells and 37 heavens of Hinduism.[67]

On the eastern gallery is one of the most celebrated scenes, the Churning of the Sea of Milk, showing 92[68] asuras and 88 devas using the serpent Vasuki to churn the sea under Vishnu's direction (Mannikka counts only 91 asuras and explains the asymmetrical numbers as representing the number of days from the winter solstice to the spring equinox, and from the equinox to the summer solstice).[69] It is followed by Vishnu defeating asuras (a 16th-century addition). The northern gallery shows Krishna's victory over Bana (where according to Glaize, "The workmanship is at its worst").[70]

Angkor Wat is decorated with depictions of apsaras and devata; there are more than 1,796 depictions of devata in the present research inventory.[71] Angkor Wat architects employed small apsara images (30–40 cm or 12–16 in) as decorative motifs on pillars and walls. They incorporated larger devata images (all full-body portraits measuring approximately 95–110 cm or 37–43 in) more prominently at every level of the temple from the entry pavilion to the tops of the high towers. In 1927, Sappho Marchal published a study cataloging the remarkable diversity of their hair, headdresses, garments, stance, jewellery, and decorative flowers, which Marchal concluded were based on actual practices of the Angkor period.[72]

Construction techniques

The monument was made of five to ten million sandstone blocks with a maximum weight of 1.5 tons each.[73] The entire city of Angkor used far greater amounts of stone than all the Egyptian pyramids combined and occupied an area significantly greater than modern-day Paris. Moreover, unlike the Egyptian pyramids, which use limestone quarried 0.5 km (1⁄4 mi) away, the entire city of Angkor was built with sandstone quarried 40 km (25 mi) (or more) away.[74] This sandstone was transported from Mount Kulen, a quarry approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast.[75]

The route has been suggested to span 35 kilometres (22 mi) along a canal towards Tonlé Sap lake, another 35 kilometres (22 mi) crossing the lake, and finally 15 kilometres (9 mi) against the current along Siem Reap River, making a total journey of 90 kilometres (55 mi). However, Etsuo Uchida and Ichita Shimoda of Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan have discovered in 2011 a shorter 35-kilometre (22 mi) canal connecting Mount Kulen and Angkor Wat using satellite imagery. The two believe that the Khmer used this route instead.[75]

Virtually all of its surfaces, columns, lintels and even roofs are carved. There are kilometres of reliefs illustrating scenes from Indian literature including unicorns, griffins, winged dragons pulling chariots, as well as warriors following an elephant-mounted leader, and celestial dancing girls with elaborate hairstyles. The gallery wall alone is decorated with almost 1,000 m2 (11,000 sq ft) of bas reliefs. Holes on some of the Angkor walls indicate that they may have been decorated with bronze sheets. These were highly prized in ancient times and were prime targets for robbers.[76]

While excavating Khajuraho, Alex Evans, a stonemason, and sculptor recreated a stone sculpture under 1.2 metres (4 ft), this took about 60 days to carve.[76] Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehner also conducted experiments to quarry limestone which took 12 quarrymen 22 days to quarry about 400 tons of stone.[77] The labour force to quarry, transport, carve and install so much sandstone probably ran into the thousands including many highly skilled artisans. The skills required to carve these sculptures were developed hundreds of years earlier, as demonstrated by some artefacts that have been dated to the seventh century, before the Khmer came to power.[26][47]

Angkor Wat in the present

Restoration and conservation

As with most other ancient temples in Cambodia, Angkor Wat has faced extensive damage and deterioration by a combination of plant overgrowth, fungi, ground movements, war damage, and theft. The war damage to Angkor Wat's temples however has been very limited, compared to the rest of Cambodia's temple ruins, and it has also received the most attentive restoration.[33]

The restoration of Angkor Wat in the modern era began with the establishment of the Conservation d'Angkor (Angkor Conservancy) by the École française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO) in 1908; before that date, activities at the site were primarily concerned with exploration.[78][79] The Conservation d'Angkor was responsible for the research, conservation, and restoration activities carried out at Angkor until the early 1970s,[80] and a major restoration of Angkor was undertaken in the 1960s.[81]

Work on Angkor was abandoned during the Khmer Rouge era and the Conservation d'Angkor was disbanded in 1975.[82] Between 1986 and 1992, the Archaeological Survey of India carried out restoration work on the temple,[83] as France did not recognise the Cambodian government at the time. Criticisms have been raised about both the early French restoration attempts and the later Indian work, with concerns over the damage done to the stone surface by the use of chemicals and cement.[33][84][85]

In 1992, following an appeal for help by Norodom Sihanouk, Angkor Wat was listed in UNESCO's World Heritage in Danger (later removed in 2004) and as a World Heritage Site together with an appeal by UNESCO to the international community to save Angkor.[86][87] Zoning of the area was designated to protect the Angkor site in 1994,[88] APSARA was established in 1995 to protect and manage the area, and a law to protect Cambodian heritage was passed in 1996.[89][90]

Several countries such as France, Japan, and China are now involved in Angkor Wat conservation projects. The German Apsara Conservation Project (GACP) is working to protect the devatas, and other bas-reliefs that decorate the temple, from damage. The organisation's survey found that around 20% of the devatas were in very poor condition, mainly because of natural erosion and deterioration of the stone but in part also due to earlier restoration efforts.[91] Other work involves the repair of collapsed sections of the structure, and prevention of further collapse: the west facade of the upper level, for example, has been buttressed by scaffolding since 2002,[92] while a Japanese team completed the restoration of the north library of the outer enclosure in 2005.[93]

Microbial biofilms have been found degrading sandstone at Angkor Wat, Preah Khan, and the Bayon and West Prasat in Angkor. The dehydration- and radiation-resistant filamentous cyanobacteria produce organic acids that degrade the stone. A dark filamentous fungus was found in internal and external Preah Khan samples, while the alga Trentepohlia was found only in samples taken from external, pink-stained stone at Preah Khan.[94] Replicas have been made to replace some of the lost or damaged sculptures.[95]

Tourism

Since the 1990s, Angkor Wat has become a major tourist destination. In 1993, there were only 7,650 visitors to the site;[96] by 2004, government figures show that 561,000 foreign visitors had arrived in Siem Reap province that year, approximately 50% of all foreign tourists in Cambodia.[97] The number reached over a million in 2007,[98] and over two million by 2012.[99] Most visited Angkor Wat, which received over two million foreign tourists in 2013,[100] and 2.6 million by 2018.[101]

The site was managed by the private SOKIMEX group between 1990 and 2016,[102] which rented it from the Cambodian government. The influx of tourists has so far caused relatively little damage, other than some graffiti. Ropes and wooden steps have been introduced to protect the bas-reliefs and floors, respectively. Tourism has also provided some additional funds for maintenance—as of 2000 approximately 28% of ticket revenues across the entire Angkor site was spent on the temples—although most work is carried out by teams sponsored by foreign governments rather than by the Cambodian authorities.[103]

Since Angkor Wat has seen significant growth in tourism throughout the years, UNESCO and its International Co-ordinating Committee for the Safeguarding and Development of the Historic Site of Angkor (ICC), in association with representatives from the Royal Government and APSARA, organised seminars to discuss the concept of "cultural tourism".[104] Wanting to avoid commercial and mass tourism, the seminars emphasised the importance of providing high-quality accommodation and services for the Cambodian government to benefit economically, while also incorporating the richness of Cambodian culture.[104] In 2001, this incentive resulted in the concept of the "Angkor Tourist City" which would be developed about traditional Khmer architecture, contain leisure and tourist facilities, and provide luxurious hotels capable of accommodating large numbers of tourists.[104]

The prospect of developing such large tourist accommodations has encountered concerns from both APSARA and the ICC, claiming that previous tourism developments in the area have neglected construction regulations and that more of these projects have the potential to damage landscape features.[104] Also, the large scale of these projects have begun to threaten the quality of the nearby town's water, sewage, and electricity systems.[104] It has been noted that such high frequency of tourism and growing demand for quality accommodations in the area, such as the development of a large highway, has had a direct effect on the underground water table, subsequently straining the structural stability of the temples at Angkor Wat.[104]

Locals of Siem Reap have also voiced concern that the charm and atmosphere of their town have been compromised to entertain tourism.[104] Since this local atmosphere is the key component to projects like Angkor Tourist City, the local officials continue to discuss how to successfully incorporate future tourism without sacrificing local values and culture.[104]

At the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2012, it was agreed that Borobudur and Angkor Wat would become sister sites and the provinces sister provinces.[105]

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to travel restrictions being introduced across the world, which had a severe impact on Cambodia's tourism sector. As a result, visitors to Angkor Wat plummeted, leaving the usually crowded complex almost deserted.[106][107][108] Cambodia, including Angkor Wat, reopened to international visitors in late 2021, but as of the end of 2022 had only received a fraction of its pre-pandemic traffic: a total of 280,000 tourists visited the complex in 2022, versus 2.6 million in 2018.[109] In 2023, the temple is seeing an increase in numbers over the previous year, having over 400,000 tourists by late July.[110]

See also

References

- ↑ "Angkor Wat". National Geographic Society. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ "Largest religious structure". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ↑ Atlas of the World's Religions. Oxford university press. p. 93.

- 1 2 Ashley M. Richter (8 September 2009). "Recycling Monuments: The Hinduism/Buddhism Switch at Angkor". CyArk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Higham, C. (2014). Early Mainland Southeast Asia. Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd. pp. 372, 378–379. ISBN 978-616-7339-44-3.

- 1 2 Jarus, Owen (5 April 2018). "Angkor Wat: History of Ancient Temple". Live Science. Purch. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Khmer dictionary adopted from Khmer dictionary of Buddhist institute of Cambodia, p. 1424, pub. 2007

- ↑ Chuon Nath Khmer Dictionary (1966, Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh)

- ↑ Cambodian-English Dictionary by Robert K. Headley, Kylin Chhor, Lam Kheng Lim, Lim Hak Kheang, and Chen Chun (1977, Catholic University Press)

- 1 2 Falser, Michael (16 December 2019). Angkor Wat – A Transcultural History of Heritage: Volume 1: Angkor in France. From Plaster Casts to Exhibition Pavilions. Volume 2: Angkor in Cambodia. From Jungle Find to Global Icon. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-11-033584-2. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- 1 2 "Angkor Wat". www.apsaraauthority.gov.kh. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- 1 2 Miksic, John; Yian, Goh (14 October 2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge. p. 378. ISBN 9781317279044. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ↑ Divākarapaṇḍita. (n.d.). Britannica. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Divakarapandita Archived 19 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 "Angkor Wat | Description, Location, History, Restoration, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- 1 2 "Angkor Wat, 1113–1150". The Huntington Archive of Buddhist and Related Art. College of the Arts, The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ Glaize, The Monuments of the Angkor Group p. 59.

- ↑ Masako Fukawa; Stan Fukawa (6 November 2014). "Japanese Diaspora – Cambodia". Discover Nikkei. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Abdoul-Carime Nasir. "Au-dela du plan Japonais du XVII siècle d'Angkor Vat, (A XVII century Japanese map of Angkor Wat)" (PDF). Bulletin de l'AEFEK (in French). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "History of Cambodia, Post-Angkor Era (1431 – present day)". Cambodia Travel. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Sotheavin, Nhim. "CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE FALL OF LONGVEK".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Kim, Jinah (2001). Reading Angkor Wat: A History of Oscillating Identity. University of California, Berkeley. p. 31. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ Quoted in Brief Presentation by Venerable Vodano Sophan Seng Archived 23 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Das Geheimnis von Angkor Wat". Der Tagesspiegel Online (in German). 19 January 2014. ISSN 1865-2263. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- 1 2 Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Southeast Asia: A Past Regained (1995). pp. 67–99

- ↑ Penny Edwards (2007).Cambodge: The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860–1945 ISBN 978-0-8248-2923-0

- ↑ KARNJANATAWE, K. (2015, November 26). See the sights of Sa Kaeo. Bangkok Post. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.bangkokpost.com/travel/777225/see-the-sights-of-sa-kaeo Archived 31 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Falser, Michael (2013). From Gaillon to Sanchi, from Vézelay to Angkor Wat. The Musée Indo-Chinois in Paris: A Transcultural Perspective on Architectural Museums. Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Glaize p. 59.

- ↑ Kuster, Brigitta. "On the international colonial exhibition in Paris 1931 | transversal texts". transversal.at. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ Falser, Michael: Clearing the Path towards Civilization – 150 Years of "Saving Angkor". In: Michael Falser (ed.) Cultural Heritage as Civilizing Mission. From Decay to Recovery. Springer: Heidelberg, New York, pp. 279–346.

- 1 2 3 Russell Ciochon & Jamie James (14 October 1989). "The Battle of Angkor Wat". New Scientist. pp. 52–57. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ Flags of the World, Cambodian Flag History Archived 13 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Falser, Michael (2011). Krishna and the Plaster Cast. Translating the Cambodian Temple of Angkor Wat in the French Colonial Period Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Recent research has transformed archaeologists' understanding of Angkor Wat and its surroundings". University of Sydney. 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ↑ J. Hackin; Clayment Huart; Raymonde Linossier; H. de Wilman Grabowska; Charles-Henri Marchal; Henri Maspero; Serge Eliseev (1932). Asiatic Mythology:A Detailed Description and Explanation of the Mythologies of All the Great Nations of Asia. p. 194. ISBN 978-81-206-0920-4. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Daguan Zhou (2007). A Record of Cambodia: The Land and Its People. Translated by Peter Harris. Silkworm Books.

- ↑ Fleming, Stuart (1985). "Science Scope: The City of Angkor Wat: A Royal Observatory on Life?". Archaeology. 38 (1): 62–72. JSTOR 41731666.

- 1 2 Freeman and Jacques p. 48.

- ↑ Glaize p. 62.

- ↑ "How countries around the world celebrate the spring equinox". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ↑ "Ankgor Wat, Cambodia". www.art-and-archaeology.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ The diplomatic envoy Zhou Da Guan sent by Emperor Temür Khan to Angkor in 1295 reported that the head of state was buried in a tower after his death, and he referred to Angkor Wat as a mausoleum

- 1 2 Higham, The Civilization of Angkor p. 118.

- 1 2 Scarre, Chris, ed. (1999). The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 81–85.

- ↑ Mannikka, Eleanor. "Angkor Wat, 1113–1150". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. (This page does not cite an author's name.)

- ↑ Stencel, Robert; Gifford, Fred; Morón, Eleanor (1976). "Astronomy and Cosmology at Angkor Wat". Science. 193 (4250): 281–287. Bibcode:1976Sci...193..281S. doi:10.1126/science.193.4250.281. PMID 17745714. (Mannikka, née Morón)

- ↑ Transcript of Atlantis Reborn Archived 16 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, broadcast BBC2 4 November 1999.

- ↑ Ishizawa, Yoshiaki (2015). "The World's Oldest Plan of Angkor Vat: The Japanese So-Called Jetavana, an Illustrated Plan of the Seventeenth Century". UDAYA, Journal of Khmer Studies. 13: 50.

- ↑ German Apsara Conservation Project Archived 23 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine Building Techniques, p. 5.

- ↑ Glaize p. 25.

- ↑ APSARA authority, Angkor Vat Style Archived 12 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Freeman and Jacques p. 29.

- ↑ "Ta Reach Statue at Angkor Wat in Angkor Archaeological Park, Cambodia". Encircle Photos. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ↑ Fletcher, Roland; Evans, Damian; Pottier, Christophe; Rachna, Chhay (December 2015). "Angkor Wat: An introduction". Antiquity. 89 (348): 1395. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.178. S2CID 162553313. Retrieved 27 March 2020 – via ResearchGate.

- 1 2 Freeman and Jacques p. 49.

- ↑ Glaize p. 61.

- 1 2 Freeman and Jacques p. 50.

- ↑ Glaize p. 63.

- ↑ Ray, Lonely Planet guide to Cambodia p. 195.

- ↑ Ray p. 199.

- ↑ Briggs p. 199.

- ↑ Glaize p. 65.

- ↑ Higham, Early Cultures of Mainland Southeast Asia p. 318.

- ↑ Glaize p. 68.

- ↑ Glaize

- ↑ Described in Michael Buckley, The Churning of the Ocean of Milk Archived 19 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Glaize p. 69.

- ↑ Angkor Wat devata inventory – February 2010 Archived 23 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sappho Marchal, Khmer Costumes and Ornaments of the Devatas of Angkor Wat.

- ↑ Ghose, Tia (31 October 2012). "Mystery of Angkor Wat Temple's Huge Stones Solved". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Lost City of Angkor Wat". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 Uchida, Etsuo; Shimoda, Ichita (2013). "Quarries and transportation routes of Angkor monument sandstone blocks". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (2): 1158–1164. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.1158U. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.09.036. ISSN 0305-4403.

- 1 2 "Lost Worlds of the Kama Sutra" History channel

- ↑ Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids, London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 202–225 ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

- ↑ "Considerations for the Conservation and Presentation of the. Historic City of Angkor" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. p. 65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "The Siem Reap Centre, Cambodia". EFEO. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Modern Period: The creation of the Angkor Conservation". APSARA Authority. Archived from the original on 12 February 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Cambodia. Lonely Planet. 2010. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-74179-457-1.

- ↑ Kapila D. Silva; Neel Kamal Chapagain, eds. (2013). Asian Heritage Management: Contexts, Concerns, and Prospects. Routledge. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-0-415-52054-6.

- ↑ "Activities Abroad#Cambodia". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ↑ Phillip Shenon (21 June 1992). "Washing Buddha's Face". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ Kapila D. Silva; Neel Kamal Chapagain, eds. (2013). Asian Heritage Management: Contexts, Concerns, and Prospects. Routledge. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-415-52054-6. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Michael Falser, ed. (2015). Cultural Heritage as Civilizing Mission: From Decay to Recovery. Springer International. p. 253. ISBN 978-3-319-13638-7. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Albert Mumma; Susan Smith (2012). Poverty Alleviation and Environmental Law. ElgarOnline. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-78100-329-9. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Royal Decree establishing Protected Cultural Zones". APSARA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Yorke M. Rowan; Uzi Baram (2004). Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past. AltaMira Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-7591-0342-9. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Hing Thoraxy. "Achievement of "APSARA". Archived from the original on 3 March 2001.

- ↑ German Apsara Conservation Project Archived 5 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Conservation, Risk Map, p. 2.

- ↑ "Infrastructures in Angkor Park". Yashodhara no. 6: January – June 2002. APSARA Authority. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ↑ "The Completion of the Restoration Work of the Northern Library of Angkor Wat". APSARA Authority. 3 June 2005. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ↑ Gaylarde CC; Rodríguez CH; Navarro-Noya YE; Ortega-Morales BO (February 2012). "Microbial biofilms on the sandstone monuments of the Angkor Wat Complex, Cambodia". Current Microbiology. 64 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1007/s00284-011-0034-y. PMID 22006074. S2CID 14062354.

- ↑ Guy De Launey (21 August 2012). "Restoring ancient monuments at Cambodia's Angkor Wat". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Justine Smith (25 February 2007). "Tourist invasion threatens to ruin glories of Angkor Wat". The Observer. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Executive Summary from Jan–Dec 2005". Tourism of Cambodia. Statistics & Tourism Information Department, Ministry of Tourism of Cambodia. Archived from the original on 13 April 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- ↑ "Tourism Statistics: Annual Report" (PDF). Ministry of Tourism. p. 60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ↑ "Tourism Annual Report 2012" (PDF). Ministry of Tourism. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ "Ticket sales at Angkor Wat exceed 2 million". The Phnom Penh Post. 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ↑ Cheng Sokhorng (2 January 2019). "Angkor hosts 2.6M visitors". The Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ Vannak, Chea (2 January 2019). "Ticket revenue at Angkor complex up 8 percent". Khmer Times. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ↑ Tales of Asia, Preserving Angkor: Interview with Ang Choulean (13 October 2000) Archived 17 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Winter, Tim (2007). "Rethinking tourism in asia". Annals of Tourism Research. 34: 27–44. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.004.

- ↑ "Borobudur, Angkor Wat to become sister sites". The Jakarta Post. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Tourists amazed about seeing Angkor Wat without usual crowds". South China Morning Post. 6 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "'How Long Can We Survive?': Angkor Visitors Dip, Holiday Bump Minimal". VOD. 2 November 2020. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ Hunt, Luke. "Cambodians Reclaim Angkor Wat as Global Lockdowns Continue to Bite". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "Cambodia Relocates Angkor Wat Communities in Controversial Tourism Touch-Up". Skift. 17 March 2023. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ↑ Babis, Daniel (28 July 2023). "Why Right Now Is the Best Time to Visit Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, Cambodia". The Go Guy. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

Bibliography

- Albanese, Marilia (2006). The Treasures of Angkor (Paperback). Vercelli: White Star Publishers. ISBN 978-88-544-0117-4.

- Briggs, Lawrence Robert (1951, reprinted 1999). The Ancient Khmer Empire. White Lotus. ISBN 974-8434-93-1

- Falser, Michael (2020). Angkor Wat – A Transcultural History of Heritage. Volume 1: Angkor in France. From Plaster Casts to Exhibition Pavilions. Volume 2: Angkor in Cambodia. From Jungle Find to Global Icon. Berlin-Boston DeGruyter ISBN 978-3-11-033584-2

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). Angkor, Eighth Wonder of the World. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B0085RYW0O

- Freeman, Michael and Jacques, Claude (1999). Ancient Angkor. River Books. ISBN 0-8348-0426-3.

- Higham, Charles (2001). The Civilization of Angkor. Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-584-2

- Higham, Charles (2003). Early Cultures of Mainland Southeast Asia. Art Media Resources. ISBN 1-58886-028-0

- Hing Thoraxy. Achievement of "APSARA": Problems and Resolutions in the Management of the Angkor Area

- Jessup, Helen Ibbitson; Brukoff, Barry (2011). Temples of Cambodia – The Heart of Angkor (Hardback). Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 978-616-7339-10-8.

- Petrotchenko, Michel (2011). Focusing on the Angkor Temples: The Guidebook, 383 pages, Amarin Printing and Publishing, 2nd edition, ISBN 978-616-305-096-0

- Ray, Nick (2002). Lonely Planet guide to Cambodia (4th edition). ISBN 1-74059-111-9

External links

- Angkor Wat: Its Layout, Architecture nnd Components

- Multimedia Resources of Angkor Wat March 2023

- Angkor Wat and Angkor photo gallery by Jaroslav Poncar May 2010

- Buckley, Michael (1998). Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos Handbook. Avalon Travel Publications. Online excerpt The Churning of the Ocean of Milk retrieved 25 July 2005

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)