| Ancoats Hospital | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Ancoats Hospital in 2008 | |

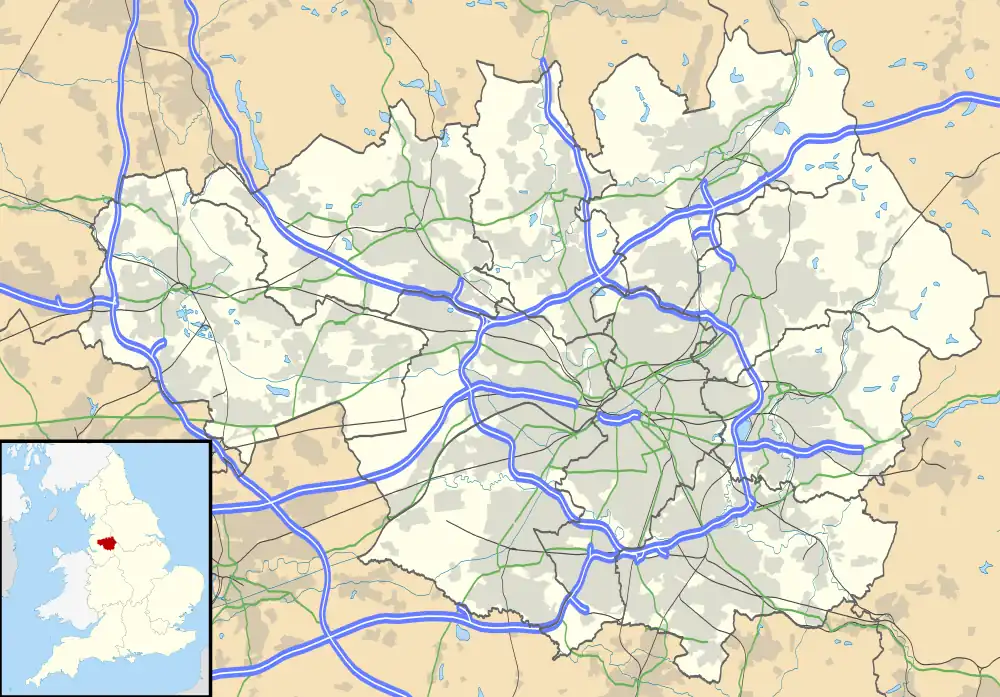

Location in Greater Manchester | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Ancoats, Manchester, England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°28′56″N 2°13′15″W / 53.48229°N 2.22084°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Public NHS |

| Type | General Hospital |

| History | |

| Opened | 1828 |

| Closed | 1989 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in England |

The Ancoats Hospital and Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary (commonly known as Ancoats Hospital) was a large inner-city hospital located in Ancoats, to the north of the city centre of Manchester, England. It was built in 1875, replacing the Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary that had existed since 1828. The building is now Grade II listed.

Background

The population of Ancoats had risen from almost nothing in the 1790s, when it was an outlying area of Manchester, to around 32,000 by the 1830s, driven by the process of industrialisation that caused Manchester to be described by many as the world's "first industrial city".[1][2][3][4][lower-alpha 1] By the 1830s, the population in the Ancoats area principally comprised Irish labourers and textile workers;[6] the area was heavily industrialised and one of the most densely populated suburbs of the city,[7] being "a mass of mean streets and courtyards zig-zagged amongst factories and canals."[8] Average life expectancy in Manchester as a whole was low, with that of a labourer in 1842 being 17 years.[3]

The origins of English charitable movements for the operation of dispensaries and other types of establishment for treatment of illness, such as hospitals, lying-in facilities and lunatic asylums, can be traced to the Georgian era. The first dispensary had been established in London by John Lettsom in 1770.[lower-alpha 2] These charitable endeavours were referred to as "voluntary hospitals" and, according to medical historian Roy Porter, "... signal[led] a new recognition on the part of influential elites that the people's health mattered."[10] The specific purpose of dispensaries was to advise and treat poor people at their homes or as outpatients, relieving some of the burden on hospital facilities and minimising the possibility of epidemics that could arise if people with infectious diseases were admitted to hospitals as inpatients. Those who attended patients under the aegis of such organisations generally did so at no charge, although they might gain social prestige and clients as a result of their actions.[12] Similarly, those who donated or subscribed to the institutions generally gained access to networking opportunities, as well as a voice in the management of the charity and the right to refer patients to it. The opportunity to police morals was thus present: the worthy-but-poor sick might be favoured with Dispensary care but the unworthy were condemned to the ravages of the workhouse; Kevin Siena notes, for example, that "This link between morality and charitable worthiness spelled bad news for syphilitics."[13]

Dispensary

Opened on 11 August 1828 on Great Ancoats Street,[7] the Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary was a voluntary hospital largely funded by industry in the Ancoats area and by middle-class people living in nearby Ardwick. Roger Cooter and John Pickstone, both medical historians, note that,

The name gives the game away. The Dispensary did not even claim to be an expression of "community" within Ancoats; rather it expressed a dependence. Ardwick ... was twinned in philanthropy with its poorer neighbour. The subscribers of Ardwick (and beyond), including those who owned factories and businesses in Ancoats, would fund a medical charity for the hand-loom weavers, the factory workers and the labourers of Ancoats. Ancoats was a "very dependent district", meaning, of course, that the surplus value created there was returned, in part, as the gift of those who lived elsewhere.[8]

The Dispensary was intended to relieve the overburdened Manchester Infirmary (MI), which was spending more money on the area than was received from it.[7] A Dispensary on a similar model had opened at Chorlton-on-Medlock around 1825–1826 because the MI, which at that time was the only Mancunian medical institution, was unwilling to extend its services to that area due to lack of subscriptions.[14] Another such Dispensary had opened in Salford in 1827 and thus that at Ancoats was the third in the Manchester area.[8] The formation of these Dispensaries came at a time when there was an increasing debate among medical professionals and society more generally regarding the charitable model, partly because of concerns that it created a culture of dependency among the poor and partly because the growth of medical schools and universities, together with the influx of large numbers of medically qualified people who had previously been engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, was having a detrimental impact on medical incomes.[12]

George Murray, the wealthy owner of a substantial textile mill complex in the area, was the Dispensary's first president;[15] the first physician, and one of the founders,[12] was James Kay, whose Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes (1832) was in large part based on his experiences there.[6][16] Kay was one of many who perceived detrimental effects regarding charity, arguing in 1834 that it promoted poverty rather than assisted in its relief.[12] As a dispensary, there were no beds and all treatments were carried out in the homes of patients or on an outpatient basis.[17] With an expenditure of around £400 per annum, by July 1833 the Dispensary had treated over 13,000 people.[18] The demographics of the area in which it was situated — densely populated, industrialised and socio-economically deprived — caused it to deal with a lot of accidents[lower-alpha 3] and infectious diseases. Those who worked for the institution became familiar with the public health issues.[7]

The Dispensary had moved premises to Ancoats Crescent in 1850. When that site was bought for development by the Midland Railway in 1869, the Dispensary relocated to 94 Mill Street (now Old Mill Street).[7]

Hospital

A further move, to larger premises on Mill Street, was enabled by a gift and later bequest totalling £7,000[19] made by Hannah Brackenbury, a philanthropist whose origins lay in Manchester. The funds were swelled by local workers who set up a Workpeoples's Fund Committee and ensured that the institution was without debt for the first time in its history. The Brackenbury funds had provided space for 50 inpatient beds, and thus the ability to become a hospital, although there were insufficient funds to enable use to be made of this until 1879, when six of the beds came into service.[7] It was at this time that the organisation became known officially as "Ancoats Hospital and Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary", although this was generally abbreviated to "Ancoats Hospital".[20] The building was constructed to a design by Lewis and Crawcroft, the architects, between 1872 and 1874.[16] Still standing, Manchester City Council says of this initial construction

Originally the building had 3 storeys above basement level and it is probable that the ground floor typically accommodated the physician's entrance, patient's entrance and waiting rooms, sitting rooms, dispensing room and consulting rooms, with the upper floors accommodating board room, offices, library, private rooms and wards. It was also formerly characterised by a central tower structure. The Dispensary building has significance as the earliest and most architecturally notable building of the former hospital complex and largely comprises a red brick building with polychrome bands, and had steeply pitched hipped slate roofs, and is of an irregular plan, and of a gothic style.[20]

The dispensary function of the hospital became a provident dispensary in 1875; the management of this was transferred to the Manchester and Salford Provident Dispensaries Association in 1885. The provident model was intended to address the perceived abuse of charity and the costs attributable to it. Means testing was introduced by the Association, which had arrangements with hospitals for the provision of treatment, midwifery services and similar requirements as well as providing care itself for, at worst, a minimal charge. People were eligible for membership if they were unable to obtain poor relief but too impoverished to afford medical care. The members paid a joining fee and a regular subscription.[7][21][22]

An extension to the hospital was completed in 1888, providing an additional 50 beds,[7] and a further 14 existed by 1915.[23] A rural convalescent home, financed by a donation from the Crossley family and land provided by the David Lewis Trust, opened near Alderley Edge in 1904.[7]

Despite generally functioning in difficult financial circumstances, the hospital was able to innovate. It provided the city's first x-ray department in 1907 and, in 1914, Harry Platt - who was later to become a renowned orthopaedic surgeon - instituted the world's first clinic dedicated to the treatment of fractures. Platt introduced physiotherapy facilities, which were at first known as the School of Massage, in 1920 and that decade also saw the introduction of a specialist Aural department.[7]

Significant donations were recorded in a 1929 publication for the British Medical Association.[24]

| Year | Source | Amount (£) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1886 | James Jardine | 12,500 | Endowment of Jardine Ward |

| 1900 | Family of James Oliver | Not known | Outpatients Department |

| 1900 | Rothwell family | 10,000 | Endowment of Rothwell Ward |

| 1915 | Mr & Mrs J. Oliver, in memory of their son killed in World War I | Not known | Enlarged Outpatients Department, establishment of ECG and Pathology facilities |

| 1919 | Lord Cawley, in memory of three sons killed in World War I | 10,000 | Endowment of Cawley Ward |

A centenary appeal was made in 1928, seeking £100,000 to enlarge the hospital. This succeeded despite the Great Depression, allowing the provision of an additional 100 beds, an extra operating theatre, a separate casualty block, enlargements to the x-ray facilities and pathology laboratory, and a permanent massage department. There was a formal opening of these improvements in 1935.[7][24]

The Workpeoples's Fund Committee had raised much money over the years but ceased operation in 1948, in which year the National Health Service was established.[17] There was a threat of closure during the 1950s but the next two decades saw continued improvements made to the structures and facilities, including the creation of new outpatients' and accident departments. The convalescent home, which had been used by injured soldiers during World War I, was transferred to the Mary Dendy Hospital in 1967[lower-alpha 4] and the ability to deal with accident cases was lost in 1979, when that responsibility was transferred to North Manchester General Hospital. The plan had been for the hospital to move away from being a general hospital and to function as a specialist orthopaedics unit. It was closed in 1989.[7]

Present state

Elizabeth Gaskell refers to Ancoats Dispensary in her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life. L. S. Lowry painted a picture of the outpatients' waiting hall in 1952.[25]

As of 2013, the main Dispensary building, which was Grade II listed in 1974,[26] was under threat of demolition after the developer, Urban Splash, claimed that it was unable to find an economically viable use for it.[27] Urban Splash's application for listed building demolition was being considered by Manchester City Council.[28] The Victorian Society in Manchester described it as "a roofless shell secured by scaffolding" in 2012 and noted that it was on a list of "Top Ten Endangered Victorian Buildings".[29][lower-alpha 5] With the exception of the main building, which covers an area of around 760 square metres (8,200 sq ft), all structures on the site — such as ward blocks, various extensions, a nurses' home and ancillary buildings — had already been demolished. Some aspects of the main building had also been removed, including much of the central tower.[20]

The Ancoats Dispensary Group campaigned to restore the Dispensary building and reopen it as a community centre with offices and meeting spaces. The Heritage Lottery Fund provided £771,700 of funding to the project in June 2014, however the group was not able to raise £800,000 of matching funds, and a second round of funding of £4.28 million was not awarded, with concerns that the cost of the restoration would increase and about the sustainability of the project.[30]

Notable people

- Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth[31]

- Sir Harry Platt, orthopaedic surgeon[32]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The population of Manchester as a whole rose from 41,032 to 270,901 between 1774 and 1831.[3] Much of this growth was fuelled by people migrating to the area in search of work, and in 1851 over half the population had not been born there.[5]

- ↑ Roy Porter variously gives the foundation date of the first dispensary as 1770[9] and 1773;[10] most sources, such as Anne Digby, say that this, the Aldersgate General Dispensary, began in 1770.[11]

- ↑ Treatment of accidents at Ancoats amounted to 25 per cent of all cases around 1830, compared to 20 per cent at the Salford Dispensary and 15 per cent at Chorlton.[15]

- ↑ According to The National Archives, the conditions in urban areas had improved to such an extent by 1967 that it was deemed no longer necessary for people to spend a fortnight convalescing in a rural environment.[17] The University of Manchester says that it had become a centre for the treatment of children suffering from tuberculosis of the spine.[7]

- ↑ The building also no longer has floors.[20]

Citations

- ↑ Peck, Jamie; Ward, Kevin (2002). "Placing Manchester". In Peck, Jamie; Ward, Kevin (eds.). City of Revolution: Restructuring Manchester. Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7190-5888-2.

- ↑ Hall, Peter (1998). "The First Industrial City: Manchester 1760–1830". Cities in Civilisation: Culture, Innovation and Urban Order. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-297-84219-4.

- 1 2 3 Kim, Yeong-Hyun; Short, John Rennie (2008). Cities and Economies. Abingdon & New York: Routledge. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-0-415-36574-1.

- ↑ Pickstone, John V. (1985). Medicine and Industrial Society: A History of Hospital Development in Manchester and Its Region, 1752–1946. Manchester University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-7190-1809-1.

- ↑ Mathias, Peter (1983) [1969]. The First Industrial Nation: An Economic History of Britain 1700–1914 (2nd ed.). London & New York: Methuen. pp. 177–178. ISBN 0-416-33290-0.

- 1 2 Mort, Frank (2002). Dangerous Sexualities: Medico-Moral Politics in England Since 1830 (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-0-203-44756-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Ancoats Hospital — ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands". University of Manchester.

- 1 2 3 Cooter, Roger; Pickstone, John (1993). "From Dispensary to Hospital: Medicine, Community and Workplace in Ancoats, 1828–1948". Manchester Regional History Review (7).

- ↑ Payne, J. F. (2004). "Lettsom, John Coakley (1744–1815)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. revised Porter, Roy. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 July 2013.(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- 1 2 Porter, Roy (1995). Disease, Medicine and Society in England, 1550–1860 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-521-55791-7.

- ↑ Digby, Anne (2002). Making a Medical Living: Doctors and Patients in the English Market for Medicine, 1720–1911. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-521-52451-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Michael (December 2009). "Medicine, Reform and the 'End' of Charity in Early Nineteenth-Century England". English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. CXXIV (511): 1353–1388. doi:10.1093/ehr/cep347.

- ↑ Siena, Kevin (2009). "Stage-Managing a Hospital in the Eighteenth Century: Visitation at the London Lock Hospital". In Mooney, Graham; Reinarz, Jonathan (eds.). Permeable Walls: Historical Perspectives on Hospital and Asylum Visiting. Rodopi. p. 177. ISBN 978-90-420-2599-8.

- ↑ "Chorlton-on-Medlock Dispensary — ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands". University of Manchester. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- 1 2 Pickstone, John V. (1985). Medicine and Industrial Society: A History of Hospital Development in Manchester and Its Region, 1752–1946. Manchester University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-7190-1809-1.

- 1 2 Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2001). Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East. Pevsner Architectural Guides. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-300-10583-4.

- 1 2 3 "Ancoats Hospital". The National Archives. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Panorama of Manchester. J. Everett. 1834. p. 111.

- ↑ Pickstone, John V. (1985). Medicine and Industrial Society: A History of Hospital Development in Manchester and Its Region, 1752–1946. Manchester University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7190-1809-1.

- 1 2 3 4 "Manchester City Council Planning and Highways Committee". Manchester City Council. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Manchester and Salford Provident Dispensaries Association — ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands". University of Manchester. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Provident Dispensaries — ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands". University of Manchester. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ McKechnie, H. M. (1915). Manchester in 1915. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 57. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- 1 2 Brockbank, E. M., ed. (1929). The Book of Manchester and Salford Written for the 97th Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association. Manchester: George Falkner. pp. 126–27.

- ↑ "Ancoats Hospital Outpatients' Hall". BBC. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Ardwick and Ancoats Hospital, Manchester". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ "Ancoats Dispensary 'Not Viable' says Heritage Works". Manchester Confidential. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ "Ancoats Dispensary given 'final chance' to secure restoration funding". BBC. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Autumn Newsletter, 2012" (PDF). The Manchester Victorian Society. Autumn 2012. pp. 2, 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ Britton, Paul (24 October 2017). "Lottery bosses explain why they rejected funding bid to save Ancoats Dispensary". men.

- ↑ "Sir James Phillips Kay-Shuttleworth (1804-1877)". historyhome.co.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ↑ Pickstone, John (19–26 December 1987). "Manchester's History And Manchester's Medicine". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). BMJ Publishing Group. 295 (6613): 1604–1608. doi:10.1136/bmj.295.6613.1604. JSTOR 29529232. PMC 1257489. PMID 3121091.

Further reading

- Brockbank, E. M. (1936). The Foundation of Provincial Medical Education in England. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Brockbank, William (1965). The Honorary Medical Staff of the Manchester Royal Infirmary, 1830–1948. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kay, James Phillips (1832). The moral and physical condition of the working classes employed in the cotton manufacture in Manchester. JSTOR 60242614. (subscription required)

- Ancoats Hospital: An Archaeological Photographic Survey of a Late Nineteenth Century Corridor Hospital Site. Manchester: University of Manchester Archaeological Unit. 2003.

External links

- "Medical Charities in Manchester — ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands". University of Manchester.