| Arthropleura | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of A. armata at the Senckenberg Museum of Frankfurt | |

| |

| Life restoration of Arthropleura, head anatomy hypothetically reconstructed after Microdecemplex | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Myriapoda |

| Class: | Diplopoda |

| Subclass: | †Arthropleuridea |

| Order: | †Arthropleurida Waterlot, 1933 |

| Family: | †Arthropleuridae Zittel, 1885 |

| Genus: | †Arthropleura Meyer, 1854 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Arthropleura (Greek for 'jointed ribs') is an extinct genus of massive millipedes that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 345 to 290 million years ago,[1][2] from the Viséan stage of the lower Carboniferous Period to the Sakmarian stage of the lower Permian Period.[1][3] The species of the genus are the largest known land invertebrates of all time, and would have had few, if any, predators.

Morphology

A. armata grew to be 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) long.[4] Tracks from Arthropleura up to 50 centimetres (20 in) wide have been found at Joggins, Nova Scotia.[5] In 2021 a fossil, probably a shed exoskeleton (exuviae) of an Arthropleura, was reported with an estimated width of 55 centimetres (22 in), length of 1.9 metres (6 ft 3 in) to 2.63 metres (8 ft 8 in) and body mass of 50 kg (110 lb).[2][1] It is one of the largest arthropods ever known, as large as the eurypterid Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, whose length is estimated at 2.33–2.59 metres (7 ft 8 in – 8 ft 6 in).[6] Arthropleura was able to grow larger than modern arthropods, partly because of the greater partial pressure of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere during the lower Carboniferous and partly because of the lack of large terrestrial vertebrate predators.[7] However, large-sized specimens of Arthropleura are described from the Serpukhovian stage, during which the oxygen pressure was only a bit higher than modern Earth at around 23 percent, suggesting that high oxygen pressure may not have been a primary reason for its gigantism.[1]

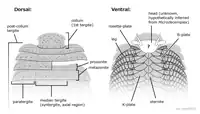

Diagrammatic reconstruction of A. armata

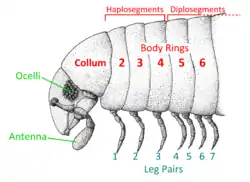

Diagrammatic reconstruction of A. armata Anterior morphology of A. armata

Anterior morphology of A. armata Modern millipede anatomy for comparison

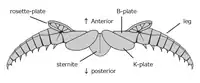

Modern millipede anatomy for comparison Leg and associated structures

Leg and associated structures

Arthropleura is characterized by a series of well-developed tergites (dorsal exoskeleton) having three lobes like a trilobite, with dorsal surfaces covered by many tubercles. The head is almost unknown, as the anterior oval plate in front of the first trilobate tergite, which previous thought to be head shield, were considered to be a collum (first tergite of millipede trunk) by subsequent studies.[8][9] Based on the discovery from other arthropleurids (Microdecemplex), the head may have had non-filamentous antennae and trumpet-like organs.[10] It is estimated that Arthropleura had a trilobate tergite number ranging from 28 to 32.[1] The alignment between leg and tergite is not well understood, but at least it is believed to have been diplopodous in some degree: two pairs of legs per tergite, like modern millipede.[10][9] Alongside the median sternite, there were three pairs of ventral plates located around each leg pair, namely K-, B- and rosette plates, and either the B- or K-plates were thought to be respiratory organs.[8][9][11] The body terminated with a trapezoidal telson.[9]

Paleobiology

All found fossils of Arthropleura are believed to be exuviae (molting shells) instead of carcasses.[11] The good preservation of its thin exuviae, buttressing plates around the leg base, and evidence of 3 cm deep trackway fossils (namely the ichnotaxon Diplichnites cuithensis[12][13]) altogether suggests that they had a sturdy exoskeleton and roamed the land.[1] Arthropleura was once thought to have lived mainly in coal forests.[9] However, it probably lived a forest-independent life, as fossils of the trackway were found in more open areas and fossils were found even after the Carboniferous rainforest collapse.[1]

There is no solid evidence for the diet of Arthropleura, as the fossils that were once considered coprolites, including lycopod fragments and pteridophyte spores,[14] are later considered to be merely coexistence of plant fossils and exuvia remains.[8] Nonetheless, the interpretation of a herbivorous diet is still accepted, and it is estimated that Arthropleura may have eaten not only spores but also sporophylls and seeds, based on its enormous size that possibly required lots of nutrition.[11]

Extinction

Previously, the extinction of Arthropleura was attributed to the decrease of coal forest.[15] However, many fossils have been discovered even after the Carboniferous rainforest collapse, and it is estimated that Arthropleura itself lived a forest-independent life. A more recent proposal is that the diversification of tetrapods and the desiccation of the equator caused it to become extinct.[1][11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Davies, Neil S.; Garwood, Russell J.; McMahon, William J.; Schneider, Joerg W.; Shillito, Anthony P. (Dec 21, 2021). "The largest arthropod in Earth history: insights from newly discovered Arthropleura remains (Serpukhovian Stainmore Formation, Northumberland, England)". Journal of the Geological Society. 179 (3). doi:10.1144/jgs2021-115. S2CID 245401499.

- 1 2 "Largest-ever millipede fossil found on Northumberland beach". BBC News. 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ↑ Martino, Ronald L.; Greb, Stephen F. (2009). "Walking trails of the giant terrestrial arthropod Arthropleura from the Upper Carboniferous of Kentucky". Journal of Paleontology. 83 (1): 140–146. doi:10.1666/08-093R.1.Archived 2019-12-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mcghee, George R. Jr (2013-11-12). When the Invasion of Land Failed: The Legacy of the Devonian Extinctions. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231160575.

- ↑ "The Excitement of Discovery". Virtual Museum of Canada. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved 2006-04-17.

- ↑ Braddy, Simon J; Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2008-02-23). "Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod". Biology Letters. 4 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. PMC 2412931. PMID 18029297.

- ↑ M. G. Lockley & Christian Meyer (2013). "The tradition of tracking dinosaurs in Europe". Dinosaur Tracks and Other Fossil Footprints of Europe. Columbia University Press. pp. 25–52. ISBN 9780231504607.

- 1 2 3 Sues, Hans-Dieter. "Largest Land-Dwelling "Bug" of All Time". National Geographic. Ford Cochran. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kraus, O.; Brauckmann, C. (2003-05-05). "Fossil giants and surviving dwarfs. Arthropleurida and Pselaphognatha (Atelocerata, Diplopoda): characters, phylogenetic relationships and construction". Verhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg. 40: 5–50.

- 1 2 Wilson, Heather M.; Shear, William A. (1999). "Microdecemplicida, a new order of minute arthropleurideans (Arthropoda: Myriapoda) from the Devonian of New York State, U.S.A." Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 90 (4): 351–375. doi:10.1017/S0263593300002674. S2CID 129597005.

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider, Joerg; Lucas, Spencer; Werneburg, Ralf; Rößler, Ronny (2010-05-01). "Euramerican Late Pennsylvanian/Early Permian arthropleurid/tetrapod associations – implications for the habitat and paleobiology of the largest terrestrial arthropod". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 49: 49–70.

- ↑ Adrian P. Hunt; Spencer G. Lucas; Allan Lerner; Joseph T. Hannibal (2004). "The giant Arthropleura trackway Diplichnites cuithensis from the Cutler Group (Upper Pennsylvanian) of New Mexico". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 36 (5): 66. Archived from the original on 2015-09-28. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- ↑ D. E. Briggs; A. G. Plint & R. K. Pickerill (1984). "Arthropleura trails from the Westphalian of eastern Canada" (PDF). Palaeontology. 27 (4): 843–855. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- ↑ A. C. Scott; W. G. Chaloner & S. Paterson (1985). "Evidence of pteridophyte–arthropod interactions in the fossil record" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 86B: 133–140.

- ↑ Thom Holmes (2008). "The first land animals". March Onto Land: the Silurian Period to the Middle Triassic Epoch. The Prehistoric Earth. Infobase Publishing. pp. 57–84. ISBN 9780816059591.

External links

- Lyall I. Anderson; Jason A. Dunlop; Carl A. Horrocks; Heather M. Winkelmann; R. M. C. Eagar (1998). "Exceptionally preserved fossils from Bickershaw, Lancashire UK (Upper Carboniferous, Westphalian A (Langsettian))". Geological Journal. 32 (3): 197–210. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-1034(199709)32:3<197::aid-gj739>3.0.co;2-6.