Ashland, Kentucky | |

|---|---|

Downtown Ashland in 2019 | |

Flag Logo | |

| Motto: A proud past. A bright future. | |

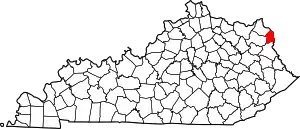

Location of Ashland in Boyd County, Kentucky | |

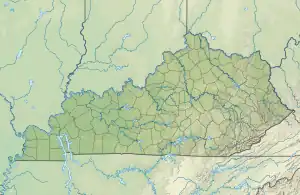

Ashland Location in Kentucky  Ashland Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 38°27′50″N 082°38′30″W / 38.46389°N 82.64167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kentucky |

| County | Boyd |

| Settled | Poage's Landing, 1786 |

| Incorporated | Ashland, 1854 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Matt Perkins |

| • City Manager | Michael Graese |

| Area | |

| • City | 10.77 sq mi (27.89 km2) |

| • Land | 10.73 sq mi (27.80 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 551 ft (168 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 21,625 |

| • Estimate (2022)[2] | 21,342 |

| • Density | 2,014.44/sq mi (777.76/km2) |

| • Metro | 376,155 (US: 150th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 41101, 41102, 41105 |

| Area code | 606 |

| FIPS code | 21-02368 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0486092 |

| Website | www |

Ashland is a home rule-class city[3] in Boyd County, Kentucky, United States. The largest city in Boyd County, Ashland is located upon a southern bank of the Ohio River at the state border with Ohio and near West Virginia. The population was 21,625 at the 2020 census.[4] Ashland is a principal city of the Huntington–Ashland metropolitan area, referred to locally as the "Tri-State area", home to 376,155 residents as of 2020.[1] Ashland serves as an important economic and medical center for northeastern Kentucky.

History

Ashland dates back to the migration of the Poage family from the Shenandoah Valley via the Cumberland Gap in 1786. They erected a homestead along the Ohio River and named it Poage's Landing.[5] Also called Poage Settlement, the community that developed around it remained an extended-family affair until the mid-19th century.[6] In 1854, the city name was changed to Ashland, after Henry Clay's Lexington estate and to reflect the city's growing industrial base. The city's early industrial growth was a result of the Ohio Valley's pig iron industry and, particularly, the 1854 charter of the Kentucky Iron, Coal, and Manufacturing Company by the Kentucky General Assembly.[6] The city was formally incorporated by the General Assembly two years later in 1856.[7] Major industrial employers in the first half of the 20th century included Armco, Ashland Oil and Refining Company, the C&O Railroad, Allied Chemical & Dye Company's Semet Solvay, and Mansbach Steel.

Geography

Ashland lies within the ecoregion of the Western Allegheny Plateau.[8]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.8 square miles (27.9 km2), of which 10.7 square miles (27.8 km2) is land and 0.039 square miles (0.1 km2), or 0.30%, is water.[4]

Cityscape

Ashland's central business district extends from 12th Street to 18th Street, and from Carter Avenue to Greenup Avenue. It includes many historically preserved and notable buildings, such as the Paramount Arts Center and the Ashland Bank Building, which serves as a reminder of what Ashland leaders hoped the city would become.

Climate

Ashland is in the humid subtropical climate zone, and distinctly experiences all four seasons, with vivid fall foliage and occasional snow in winter. The average high is 88 °F in July, the warmest month, with the average lows of 19 °F occurring in January, the coolest month. The highest recorded temperature was 105 °F in July 1954. The lowest recorded temperature was −25 °F in January 1994. Average annual precipitation is 42.8 inches (1,090 mm), with the wettest month being July, averaging 4.7 inches (120 mm).

| Climate data for Ashland, Kentucky (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1897–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

93 (34) |

85 (29) |

82 (28) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.8 (4.3) |

44.4 (6.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

66.6 (19.2) |

74.7 (23.7) |

82.5 (28.1) |

85.4 (29.7) |

84.3 (29.1) |

78.2 (25.7) |

66.6 (19.2) |

54.0 (12.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

34.3 (1.3) |

42.7 (5.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

71.5 (21.9) |

75.0 (23.9) |

73.6 (23.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

54.7 (12.6) |

43.2 (6.2) |

35.5 (1.9) |

53.8 (12.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.5 (−5.3) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

41.1 (5.1) |

51.2 (10.7) |

60.6 (15.9) |

64.6 (18.1) |

62.8 (17.1) |

55.6 (13.1) |

42.7 (5.9) |

32.3 (0.2) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

43.0 (6.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−23 (−31) |

−9 (−23) |

9 (−13) |

20 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

34 (1) |

30 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

10 (−12) |

2 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.51 (89) |

3.69 (94) |

4.36 (111) |

3.85 (98) |

4.85 (123) |

4.46 (113) |

4.58 (116) |

3.91 (99) |

3.32 (84) |

2.97 (75) |

2.98 (76) |

4.20 (107) |

46.68 (1,186) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.1 | 11.4 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 11.8 | 129.9 |

| Source: NOAA[9][10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,459 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,280 | 124.8% | |

| 1890 | 4,195 | 27.9% | |

| 1900 | 6,800 | 62.1% | |

| 1910 | 8,688 | 27.8% | |

| 1920 | 14,729 | 69.5% | |

| 1930 | 29,074 | 97.4% | |

| 1940 | 29,537 | 1.6% | |

| 1950 | 31,131 | 5.4% | |

| 1960 | 31,283 | 0.5% | |

| 1970 | 29,245 | −6.5% | |

| 1980 | 27,064 | −7.5% | |

| 1990 | 23,622 | −12.7% | |

| 2000 | 21,981 | −6.9% | |

| 2010 | 21,684 | −1.4% | |

| 2020 | 21,625 | −0.3% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 21,342 | [11] | −1.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of 2021, there were 21,476 people, 8,859 households, and 6,192 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,984.4 inhabitants per square mile (766.2/km2). There were 10,763 housing units at an average density of 971.7 per square mile (375.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.3% White, 1.6% African American, 0.6% Asian, 2.7% Hispanic or Latino, and 3.7% from two or more races.

There were 9,675 households, out of which 26.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 13.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.0% were non-families. 33.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.82.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.9% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 26.5% from 25 to 44, 23.7% from 45 to 64, and 19.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $45,414. Males had a median income of $35,362 versus $23,994 for females. The per capita income for the city was $26,101. About 23% of the population were below the poverty line, including 28.3% of those under age 18 and 12.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

American Rolling Mill Co. (ARMCO) opened its steel mill, Ashland Works, in 1922. The facility grew to cover 700 acres (280 ha) along the Ohio River. It set world records in production, and eventually employed about 7,000 people.[13][14] Local scrap drives were held during World War II to support production at the plant.[15]

ARMCO Steel partnered with Kawasaki Steel Corporation in 1994.[16] AK Steel eventually purchased Armco Steel Inc. At one time, Armco employed over 4,000 people at its West Works, Foundry, and Coke Plant. AK Steel employed under 1,000 after the closing of the Foundry and Coke Plant and the downsizing of its West Works. AK shut down completely in 2019.[13][17]

Arts and culture

Annual cultural events and fairs

- Festival of Trees

- Poage Landing Days

- Summer Motion

- Winter Wonderland of Lights

- Firkin Fest craft beer festival

Historical structures and museums

The Paramount Arts Center, an Art Deco style movie theater built in 1930, is located on Winchester Avenue. The converted theater serves as an important venue for the arts in eastern Kentucky and the neighboring sections of Ohio and West Virginia. It is well noted for its Festival of Trees event during the winter season. The Paramount is also devoted to teaching children the importance of the arts. Summer classes are offered for school-age children.

Also along Winchester Avenue is the Highlands Museum and Discovery Center. Among its numerous exhibits, one about Country Music Heritage pays tribute to the music artists from along U.S. Route 23 in Kentucky. Two locals, The Judds from Ashland, and Billy Ray Cyrus from nearby Flatwoods, are included.

The Pendleton Art Center, formed in 2005, is located within the downtown. The works produced include paintings, stained glass, carved gourds, and wood carvings by local artists. They are displayed at the Pendleton the first Friday and Saturday of every month and at other times by appointment.

The Jesse Stuart Foundation, an organization dedicated to the preservation of the literary legacy of Jesse Stuart and other Appalachian writers, was at one time located within an earshot of the Pendleton Arts Center. Jesse Stuart, a well-known 20th-century author, was from nearby Greenup, Kentucky.

Parks and recreation

Ashland boasts a 47-acre (190,000 m2) Central Park.

In July 1976, a new10-acre (40,000 m2) park at the former Clyffeside Park was envisioned.[6] Named after Commissioner Johnny Oliverio, it features several baseball diamonds, and is located along Winchester Avenue near 39th Street.

In 2004, the AK Steel Sports Park was constructed along Blackburn Avenue in South Ashland. The sports-oriented park features several baseball diamonds, soccer fields and an incomplete skate park.[6]

Government

Local government

Ashland is governed by a City Manager form of government.[18] The government switched from a council-manager to a city commissioner-manager form of government in 1950.[19] The City Manager is the chief administrative officer for the city who reports to a Board of Commissioners. Department heads ranging from the Police to Public Works report to the City Manager. The City Manager is currently Michael Graese.

The Mayor of Ashland is elected for a four-year term and is not term-limited. The mayor presides over City Commission meetings, is a voting member of the City Commission and represents the city at major functions. The current mayor is Matt Perkins.

Ashland's current City Commission members are Mayor Matt Perkins and Commissioners Josh Blanton, Amanda Clark, Marty Gute and Cheryl Wooten Spriggs.

In 1925, a new city hall was erected at the corner of 17th Street and Greenup Avenue.[19]

Federal representation

The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates the Federal Correctional Institution, Ashland in Summit, unincorporated Boyd County,[20][21] 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of central Ashland.[22]

The United States Postal Service operates the Ashland Post Office and the Unity Contract Station.[23][24]

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky maintains courtroom and office facilities in the Carl D. Perkins United States Courthouse & Federal Building in downtown Ashland.[25]

Education

All public schools within city limits are operated by the Ashland Independent School District. Public schools outside of city limits are operated by the Boyd County School District and the Fairview Independent School District. Some portions of the city limits are in the Boyd and Fairview school districts.[26]

Ashland has five public elementary schools, Hager Elementary, Oakview Elementary, Crabbe Elementary School, Poage Elementary and Charles Russell Elementary. Hatcher Elementary closed its doors in Spring 2010. Its students and much of its resources were consolidated with the other elementary schools in Fall 2010.[27] The former Hatcher Elementary building now serves as the Ashland Independent Schools Central Office.

There is one public middle school, Ashland Middle School, formerly known as George M. Verity Middle School and Putnam Junior High School.[28][29] The campus is home to Putnam Stadium which serves as the home field for Ashland Tomcats high school and middle school football.

One public high school serves the city of Ashland: Paul G. Blazer High School, named after philanthropist[30] and founder of Ashland Inc.,[31] Paul G. Blazer. The high school is home to the Ashland Tomcats and Kittens athletic teams. The Ashland Tomcats football program has achieved 11 state championships. The Ashland Tomcats (boys') basketball program has accomplished 1 national championship, 4 state championships, 32 regional championships, and 55 district championships. The Ashland Tomcats and Kittens (girls') soccer teams play at the Ashland Soccer Complex at the high school. The school's marching band competes in the AAA class of the Kentucky Music Educators Association(KMEA). The marching band is commonly called "The Pride of Blazer" for its excellent performance in many KMEA marching band competitions.

Westwood, an unincorporated community just outside the Ashland city limits, is served by the Fairview Independent School District. The district operates Fairview High School, grades 6–12, and Fairview Elementary School, grades K-5.

The Boyd County Public Schools serves the rural part of Ashland and the remainder of Boyd County. It has four elementary schools, those being Ponderosa Elementary, Cannonsburg Elementary, Catlettsburg Elementary and Summit Elementary. Boyd County Middle School serves grades 6–8, while Boyd County High School serves grades 9–12.

The two private schools serving the Ashland area are the Holy Family School and the Rose Hill Christian School. Holy Family is affiliated with Holy Family Catholic Church and currently offers K–12 education. Rose Hill is affiliated with the Rose Hill Baptist Church and also offers K–12.

Post-secondary educational opportunities include Ashland Community and Technical College, which has multiple campuses within the city. Morehead State University also has a satellite campus located in Ashland.

Ashland has a public library, a branch of the Boyd County Public Library.[32]

Media

Newspapers

Ashland is home to two newspapers: The Independent and The Greater Ashland Beacon.

The Daily Independent is a five-day morning daily newspaper which covers the city and the surrounding metropolitan area. In addition, it offers national, state and regional news/sports coverage via reprints of Associated Press and CNHI wire reports and columns. The newspaper is often called "The Independent" or the "Ashland Daily Independent" by locals, as these were its former names. One of the paper's claims to fame is the first printings of a supposed image of Jesus in the clouds of Korea in 1951.[33]

Ashland's other newspaper is The Greater Ashland Beacon. It is a free weekly circular published in full color every Tuesday. "The Beacon", as it is known by locals, is "hyper-local," meaning it is exclusively dedicated to covering the community. Highlights include, but are not limited to, local events, sports results, outdoor recreation and personal interest articles and columns penned by freelance Ashland-area journalists and quasi-celebrities.[34]

Radio

| Call sign | Frequency | Format | Description / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| WKAO | 91.1 FM | Contemporary Christian music | Owned by Positive Alternative Radio, Inc. Licensed to Ashland and identifies as "Walk FM". |

| WDGG | 93.7 FM | Country | Owned by Kindred Communications. Licensed to Ashland with studios located in Huntington, West Virginia. Identifies as "93.7 The Dawg". |

| WKSG | 98.3 FM | Southern gospel | Licensed to nearby Garrison, Kentucky with its transmitter tower located just outside of Garrison in Greenup County, Kentucky and its studios located in Portsmouth, Ohio. Identifies as "Hot 98.3". |

| WLGC-FM | 105.7 FM | Oldies | Owned by Greenup County Broadcasting, Inc. Licensed to nearby Greenup, Kentucky with studios located in downtown Ashland. Identifies as "Kool Hits 105.7". |

| WCMI | 1340 AM | Sports talk | Owned by Kindred Communications. It was founded by the Ashland Broadcasting Station whose owners were the Daily Independent on April 29, 1935.[19] It was sold to Nunn Enterprises in 1939. Identifies as "CAT Sports 93-3 and 1340". |

| WOKT | 1080 AM | Christian Talk & Teaching | Located in adjacent Cannonsburg, it is owned by Fowler Media Partners of South Point, Ohio. It currently simulcasts its programming on "WJEH" 990 AM of Gallipolis, Ohio.. Identifies as "The Tri-State's 24 Hour Christian Talk and Information Station ". |

Television

Ashland residents receive their network television primarily from stations in Huntington and Charleston, West Virginia. In addition, WKYT, the CBS affiliate in Lexington, Kentucky, is shown on cable TV in Ashland when its programming is different from Charleston's CBS affiliate WOWK. There are also two television stations licensed to Ashland itself. Those are:

| Call sign | Channel | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WKAS | Digital 25 | Owned by the Kentucky Authority for Educational Television. PBS/Kentucky Educational Television (KET) affiliate |

| WTSF | Digital 44 | Owned by Word of God Fellowship, Inc. Daystar affiliate |

Infrastructure

Transportation

Air

Located just northwest of the city in Worthington is the Ashland Regional Airport. This airport is used for general aviation. The then-named Ashland-Boyd County Airport opened in 1953 and featured a 5,600 ft (1,700 m). runway with a 3,000 ft (910 m). clearance.[19]

Tri-State Airport, located in nearby Huntington, West Virginia, provides commercial aviation services for the city.

Rail

Amtrak serves Ashland with the three-days-a-week Cardinal, connecting New York City, Washington, Charlottesville, VA, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Chicago. Westbound trains are scheduled to stop Sunday, Wednesday, Friday in the late evening. Eastbound the stops are early morning Wednesday, Friday, Sunday.

The Amtrak station is located at the Ashland Transportation Center, formerly the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway freight depot, located on 15th Street near the Ohio River. It does not have an Amtrak ticket counter or QuikTrak ticket machine, but E-tickets can be obtained from either Amtrak's website or mobile app.

The C&O freight depot, constructed in 1906 on the former Aldine Hotel site,[35] had become an abandoned derelict. Then in the late 1990s it was renovated to become the city's unified transportation hub.

The former C&O passenger depot, at 11th Street and Carter Avenue, had been completed in 1925 but abandoned in the 1970s in favor of a downsized depot in nearby Catlettsburg.[19] The rail lines to the building have since been removed. Today the building itself serves as the downtown branch of PNC Bank. Passenger rail service was moved from Catlettsburg to the Ashland Transportation Center in March 1998.

Bus

Greyhound Lines is the sole provider of intercity bus transportation out of Ashland. It operates out of the Ashland Transportation Center, along with the Ashland Bus System that provides five local bus routes.

Roads

Ashland is served by US 23 and US 60, several state routes, and is in close proximity to US 52 and Interstate 64. The state routes include:

- KY 5 never enters the city limits of Ashland, however does serve a sizable area surrounding the city.

- KY 168 crosses through the south Ashland region and is referred to as Blackburn Avenue and South Belmont Street.

- KY 766 Connects US 60 and 13th Street with KY 5

- KY 1012 is known as Boy Scout Road.

- KY 1134

Law enforcement

In the late 19th century, what is now the Ashland Police Department was organized when the town was still known as Poage's Landing.[18] The first executive officer was a town marshal, who was soon replaced by a professional police department.

The city of Ashland currently has 49 sworn officers, three civilian employees who function as administrative support and six parapolice who handle tasks that do not require the services of a sworn officer.[18]

Healthcare

King's Daughters Medical Center is the fourth largest hospital in Kentucky, the 465-bed non-profit institution is the city's largest employer at over 4,000 employees.[36] It offers numerous inpatient and outpatient services for the region.

In addition to King's Daughters Medical Center, another hospital, the Ashland Tuberculosis Hospital, was located on a hill above U.S. Route 60 in the Western Hills section of the city and opened in 1950.[19] It featured 100 beds and served 18 eastern Kentucky counties. It has long since been closed due to the discovery of antibiotics that successfully treat tuberculosis, eliminating its necessity. The facility has since been used as a state office building and is now owned by Safe Harbor, a secure domestic violence shelter and advocacy center.

Notable people

- Allison Anders, filmmaker and director

- Claria Horn Boom, U.S. federal judge

- Billy Ray Cyrus, country music singer, born and raised in Flatwoods, Kentucky, just outside Ashland

- Trace Cyrus, musician

- Mark Fosson, musician/songwriter

- Leigh French, actress

- Gina Haspel, former director of the CIA

- Jillian Hall, WWE Diva

- Mabel Hite, vaudeville and musical comedy performer

- Chris Jennings, running back for NFL's Cleveland Browns

- The Judds, country music duo of mother Naomi and daughter Wynonna

- Steve Kazee, Broadway and film actor

- Sonny Landham, actor and former Kentucky gubernatorial candidate

- Michele Mahone, entertainment reporter, NINE Network, Australia

- Venus Ramey, first red-haired Miss America in 1944

- Charlie Reliford, Major League Baseball umpire

- Julie Reeves, country music singer

- Jay Rhodemyre, former NFL center

- Charles Manson, leader of the Manson Family, killer

- Don Robinson, former Major League Baseball pitcher

- Robert Smedley, professional wrestler for World Championship Wrestling and World Wrestling Entertainment as Bobby Blaze

- Jean Bell Thomas, proprietress of American Folk Song Festival in Ashland area 1930 - 1972

- Alberta Vaughn, actress

- Brandon Webb, pitcher for Major League Baseball's Arizona Diamondbacks, 2006 National League Cy Young Award winner

- Keith Whitley, country music singer

- Chuck Woolery, game show host

In popular culture

- Ashland, Kentucky is mentioned at the beginning of Part 4 Chapter 2 in On the Road by Jack Kerouac.

- Ashland, Kentucky is mentioned as the location of the Rebel-Georgian Coalition camp in the NBC television series Revolution Episode 1.17 "The Longest Day" first aired May 13, 2013.

References

- Historical populations from A history of Ashland, Kentucky, 1786-1954, Ashland Centennial Committee, 1954, and Ashland City Directory, 1985.

- 1 2 "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Summary and Reference Guide to House Bill 331 City Classification Reform" (PDF). Kentucky League of Cities. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Ashland city, Kentucky". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ↑ Ashland History (2008 Baldridge, Terry L. and Powers, James C.)

- 1 2 3 4 A History of Ashland, Kentucky, 1854–2004. Ashland Bicentennial Committee. 2004. January 2, 2007.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Kentucky. Office of the Secretary of State. Land Office. "Ashland, Kentucky." Accessed July 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Level III Ecoregions of Kentucky". National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: Ashland, KY". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- 1 2 Stein, Jeff (October 25, 2019). "As a Kentucky mill shutters, steelworkers see the limits of Trump's intervention". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ↑ "AK Steel Locations: Ashland Works in Ashland, Kentucky". www.aksteel.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ↑ Daniel, Jerry. WWII Scrap Drive in Downtown Ashland, archived from the original on December 11, 2021, retrieved October 26, 2019

- ↑ Hicks, Jonathan P. (April 6, 1989). "Talking Deals; Armco's Accord With Kawasaki". The New York Times.

- ↑ Maynard, Mark (January 29, 2019). "AK Steel announces plans to shutter remaining operations at Ashland Works by end of 2019". KyForward.com. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Ashland Police Department." Ashland Police Department. December 30, 2006 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A history of Ashland, Kentucky, 1786–1954." Ashland Centennial Committee. 1954. January 2, 2007.

- ↑ "Admissions & Orientation (A&O) Handbook." Federal Correctional Institution, Ashland. 1 (1/51). Retrieved on February 1, 2011. "The Federal Correctional Institution of Ashland, Kentucky, is located five miles southwest of Ashland in Summit, Kentucky."

- ↑ "FCI Ashland Contact Information." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on February 1, 2011. "FCI ASHLAND FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTION ST. ROUTE 716 ASHLAND, KY 41105."

- ↑ "FCI Ashland." Federal Bureau of Prisons. Retrieved on February 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Post Office™ Location - ASHLAND Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on February 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Post Office™ Location - UNITY CONTRACT STATION Archived January 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on February 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Ashland | Eastern District of Kentucky | United States District Court".

- ↑ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Boyd County, KY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022. - Text list - For more detailed boundaries of the independent school districts see: "Appendix B: Maps Of Independent School Districts In Operation In FY 2014-FY 2015 Using 2005 Tax District Boundaries – Ashland ISD / Fairview ISD" (PDF). Research Report No. 415 – Kentucky's Independent School Districts: A Primer. Frankfort, KY: Office of Education Accountability, Legislative Research Commission. September 15, 2015. pp. 87 (Ashland) and 108 (Fairview) (PDF p. 101, 122/174).

- ↑ , Mike, James. "Goodbye to Hatcher." The Independent. May 30, 2010. Access date: June 5, 2010.

- ↑ , Maynard, Mark. "Board votes to change Verity to Ashland Middle School." The Independent. December 19, 2013. Access date: August 17, 2014.

- ↑ , James, Mike. "It's Ashland Middle School now." The Independent. August 13, 2014. Access date: August 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees of the University of Kentucky, "notes with sorrow the death of PAUL G. BLAZER, SR.", December 13, 1966".

- ↑ ""E Pluribus Unum!" "One Out of Many" An Oil Company Grows Through Acquisitions, An Address at Lexington by member Paul G. Blazer, American Newcomen Society, copyright 1956 (pages 5 & 6)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Kentucky Public Library Directory". Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ↑ "Jesus in the Clouds". snopes.com. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ "The Greater Ashland Beacon".

- ↑ Chappell, Edward A. "A historic preservation plan for Ashland, Kentucky." City of Ashland, April 1978. January 2, 2006.

- ↑ "About KDMC." King's Daughters Medical Center. December 31, 2006 "King's Daughters Medical Center | About KDMC". Archived from the original on January 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-01..