Aymer de Valence | |

|---|---|

| Earl of Pembroke | |

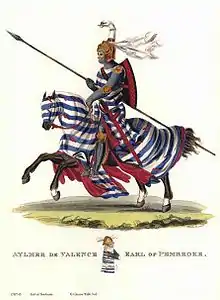

19th-century depiction of Pembroke | |

| Born | c. 1270 |

| Died | 23 June 1324 (aged 48–49) Ponthieu |

| Buried | Westminster Abbey |

| Wars and battles | |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Father | William de Valence, 1st Earl of Pembroke |

| Mother | Joan de Valence, countess of Pembroke |

Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (c. 1270 – 23 June 1324) was an Anglo-French nobleman. Though primarily active in England, he also had strong connections with the French royal house. One of the wealthiest and most powerful men of his age, he was a central player in the conflicts between Edward II of England and his nobility, particularly Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster. Pembroke was one of the Lords Ordainers appointed to restrict the power of Edward II and his favourite Piers Gaveston. His position changed with the great insult he suffered when Gaveston, as a prisoner in his custody whom he had sworn to protect, was removed and beheaded at the instigation of Lancaster. This led Pembroke into close and lifelong cooperation with the king. Later in life, however, political circumstances combined with financial difficulties would cause him problems, driving him away from the centre of power.

Though earlier historians saw Pembroke as the head of a "middle party", between the extremes of Lancaster and the king, the modern consensus is that he remained essentially loyal to Edward throughout most of his career. Pembroke was married twice, and left no legitimate issue, though he did have a bastard son. He is today remembered primarily through his wife Marie de St Pol's foundation of Pembroke College, Cambridge, and for his splendid tomb that can still be seen in Westminster Abbey. He was also an important figure in the wars surrounding the attempted English occupation of Scotland.

Family and early years

Aymer was the son of William de Valence, son of Hugh X, Count of La Marche and Isabella of Angoulême.[1] William was Henry III's half-brother through his mother's prior marriage to King John, and as such gained a central position in the Kingdom of England.[2] He had come to the earldom of Pembroke through his marriage to Joan de Munchensi, granddaughter of William Marshal.[1] Aymer was the third son of his family, so little is known of his birth and early years. He is believed to have been born some time between 1270 and 1275.[3] As his father was on crusade with Lord Edward until January 1273, a date towards the end of this period is more likely.[4] The later date is problematic, however because his mother by then was in her mid-forties. With the death in battle in Wales of his remaining brother William in 1282 (John, the elder brother, was dead in 1277), Aymer found himself heir to the Earldom of Pembroke.[4] He married Béatrice, daughter of Raoul II of Clermont, sometime before October 1295.[5]

William de Valence died in 1296, and Aymer inherited his father's French lands, but had to wait until his mother died in 1307 to succeed to the earldom.[6] In 1320, his first wife Béatrice de Clermont died. In 1321, Aymer married his second wife Marie de St Pol.[7] Through inheritance and marriages his lands consisted of—apart from the county palatine in Pembrokeshire—property spread out across England primarily in a strip from Gloucestershire to East Anglia, in south-east Ireland (Wexford), and French lands in the Poitou and Calais areas.[8]

In 1297 he accompanied Edward I on a campaign to Flanders, and seems to have been knighted by this time.[9] With his French connections he was in the following years a valuable diplomat in France for the English King.[10]

He also served as a military commander in Scotland, fighting against Robert the Bruce. In 1306 at the Battle of Methven he won the day over Bruce in a sneak attack,[11] only to be soundly defeated by Bruce at Loudoun Hill the next year.[12][13]

Ordinances and Piers Gaveston

Edward I died in 1307 and was succeeded by his son Edward II. The new king at first enjoyed the goodwill of his nobility, Valence among them.[14] Conflict soon ensued, however, connected especially with the enormous unpopularity of Edward's favourite Piers Gaveston.[15] Gaveston's arrogance towards the peers, and his control over Edward, united the Baronage in opposition to the king. In 1311 the initiative known as the Ordinances was introduced, severely limiting Royal powers in financial matters and in the appointment of officers.[16] Equally important, Gaveston was expelled from the realm, as Edward I had already done once before. Pembroke, who was not among the most radical of the Ordainers, and had earlier been sympathetic with the king, had now realised the necessity of exiling Gaveston.[17]

When Gaveston without permission returned from exile later the same year, a Baronial council entrusted Pembroke and the Earl of Surrey, with the task of taking him into custody.[18] This they did on 19 May 1312, but not long after Thomas of Lancaster, acting with the earls of Warwick, Hereford and Arundel, seized Gaveston and executed him on 19 June.[19] This act had the effect of garnering support for the king and marginalising the rebellious earls.[20] As far as Pembroke was concerned, the seizing and execution of a prisoner in his custody was a breach of the most fundamental chivalric codes, and a serious affront to his honour. The event must therefore be seen as pivotal in turning his sympathies away from the rebels and towards the king.[21]

Later years

In the following years, Pembroke worked closely with the king. He was appointed the king's lieutenant in Scotland in 1314, and was present at the disastrous English defeat at the Battle of Bannockburn, where he helped lead Edward away from the field of battle.[4] In 1317, however, while returning from a papal embassy to Avignon, he was captured by a Jean de Lamouilly, and held for ransom in Germany.[22] The ransom of £10,400 was to cause Pembroke significant financial difficulties for the remainder of his life.[23]

Although ostracised because of the murder of Gaveston, Thomas of Lancaster had regained virtual control of royal government in the period after England's defeat at Bannockburn.[24] Proving himself as incapable to rule as Edward, however, he soon grew unpopular.[25] Pembroke was one of the magnates who in the years 1316–1318 tried to prevent civil war from breaking out between the supporters of Edward and those of Lancaster, and he helped negotiate the Treaty of Leake in Nottinghamshire in 1318, restoring Edward to power.[4] Peace did not last long, however, as the king by now had taken on Hugh Despenser the Younger as another favourite, in much the same position as Gaveston.[26] Pembroke's attempts at reconciliation eventually failed, and civil war broke out in 1321. In 1322 Lancaster was defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge in what is now North Yorkshire, and executed. Pembroke was among the earls behind the conviction.[27] Also in 1322, Pembroke founded a leper hospital in Gravesend.[28]

After Boroughbridge Pembroke found himself in a difficult situation. The opponents of Hugh Despenser and his father had lost all faith in him, but at the same time, he found himself marginalised at court where the Despensers' power grew more and more complete.[4] On top of this came his financial problems. On 23 June 1324, while on an embassy to France, he suddenly collapsed and died while lodging somewhere in Picardy.[29]

Legacy

T. F. Tout in 1914, one of the first historians to make a thorough academic study of the period, considered Pembroke the one favourable exception in an age of small-minded and incompetent leaders.[30] Tout wrote of a "middle party", led by Pembroke, representing a moderate position between the extremes of Edward and Lancaster. This "middle party" supposedly took control of the royal government through the Treaty of Leake in 1318.[31] In his authoritative study of 1972, J. R. S. Phillips rejects this view. In spite of misgivings with the king's favourites, Pembroke was consistently loyal to Edward. What was accomplished in 1318 was not the takeover by a "middle party", but simply a restoration of royal power.[32]

Aymer and his sister Agnes rented one of the old manor houses of Dagenham in Essex, which has been called Valence House ever since; it is now a museum.[33]

Aymer married twice; his first marriage, before 1295, was to Beatrice, daughter of Raoul de Clermont, Lord of Nesle in Picardy and Constable of France.[34] Beatrice died in 1320, and in 1321 he married Marie de St Pol, daughter of Guy de Châtillon, Count of St Pol and Butler of France.[35] He never had any legitimate children, but he had an illegitimate son, Henry de Valence, whose mother is unknown.[4] Pembroke's most lasting legacy is probably through his second wife, who in 1347 founded Pembroke College, Cambridge.[36] The family arms are still represented on the dexter side of the college arms.[37] Aymer de Valence was buried in Westminster Abbey, where his tomb effigy can still be seen as a splendid example of late gothic architecture, elaborating on the design of the nearby tomb of Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster.[38]

Media

Aymer was portrayed by Sam Spruell in the 2018 movie Outlaw King about Robert the Bruce.

Notes

- 1 2 Phillips 1972, p. 2.

- ↑ H. W. Ridgeway, 'Valence, William de, earl of Pembroke (d. 1296)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004).

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Phillips 2004.

- ↑ "Aymer de Valence". Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 9.

- ↑ Wheater, William (1868). Temple Newsam: its history and antiquities. A. Mann, Leeds. pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 240–2.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 22.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 23–4.

- ↑ Traquair p. 137

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 24.

- ↑ Traquair p. 146

- ↑ Maddicott 1970, pp. 67–71.

- ↑ McKisack 1959, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ McKisack 1959, pp. 12–7.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 30.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, p. 32.

- ↑ Maddicott 1970, pp. 126–9.

- ↑ McKisack 1959, p. 28.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 36–7.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 111–116.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 194–197.

- ↑ Maddicott 1970, p. 160.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 191.

- ↑ McKisack 1959, p. 58.

- ↑ Maddicott 1970, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ "Milton Chantry, Gravesend". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Tout & Johnstone 1914, p. 30.

- ↑ Tout & Johnstone 1914, pp. 111–2, 144–5.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 136–77.

- ↑ "History of Valence House" (PDF). London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Phillips 1972, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Jennifer C. Ward, 'St Pol, Mary de, countess of Pembroke (c.1304–1377)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004).

- ↑ "Pembroke College, Cambridge". Pembroke College. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ↑ P. Binski, Westminster Abbey and the Plantagenets: Kingship and the Representation of Power, 1200–1400 (New Haven 1995), pp. 118–9, 176–7; M. Prestwich, Plantagenet England 1225–1360 (Oxford, 2005), p. 565.

Sources

- Maddicott, John (1970). Thomas of Lancaster, 1307–1322: a study in the reign of Edward II. London: Oxford U.P. ISBN 0-19-821837-0. OCLC 132766.

- McKisack, May (1959). The fourteenth century 1307-1399. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9. OCLC 489802855.

- Phillips, J. R. S. (1972). Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, 1307-1324: baronial politics in the reign of Edward II. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822359-5. OCLC 426691.

- Phillips, J. R. S. Valence, Aymer de, eleventh earl of Pembroke (d. 1324), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004).

- Prestwich, Michael (2007). Plantagenet England 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922687-0. OCLC 77012166.

- Tout, T. F.; Johnstone, H. (1914). The Place of the Reign of Edward II in English History. Historical series. Manchester University Press. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Traquair, Peter (1998). Freedom's Sword. University of Virginia: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 978-1570982477.