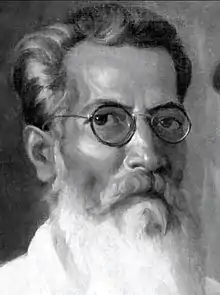

Baburao Painter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Baburao Krishnarao Mestry 3 June 1890 |

| Died | 16 January 1954 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Known for | Filmmaking Painting Sculpture |

| Notable work | Sairandhri (1920) Savkari Pash (1925) |

| Spouse |

Lakshmibai Mestry (m. 1927) |

| Children | 8 |

Baburao Krishnarao Mestry, popularly known as Baburao Painter (3 June 1890 – 16 January 1954) was an Indian filmmaker and artist.[1] He was a man of many talents with proficiency in painting, sculpture, film production, photography, and mechanical engineering.[2]

Early life

Baburao was born in a simple family on 3 June 1890 in Kolhapur, Maharashtra. He had only studied till class four or five in a Marathi medium school. His father Krishnarao Mestry was a blacksmith and carpenter by profession, but he also excelled in painting, stone and marble sculpting along with ivory carving. Baburao inherited art from his father and learned the basics of the same from him. He also taught himself to paint and sculpt in academic art school style. In the company of his cousin brother Anandrao, he also became fascinated with oil painting, photography and film making.[3]

Stage backdrop artist

Noted theatre artist Keshavrao Bhosale, the owner of Lalit Kaladarsh Natak Mandali (theater troupe), hailed from Kolhapur. In 1909, he invited the brothers to Mumbai to paint the stage backdrops for the plays.[4] Between 1910 and 1916, they painted numerous backdrops for Sangeet Natak troupes like Kirloskar Natak Mandali, plays of Bal Gandharva and Gujarati Parsi theatres. The realistic stage setting and perspective-style curtains that they painted brought them immense popularity and they emerged as leading painters of stage backdrops in Western India. For their incredible work, they were addressed with the moniker painter and subsequently came to be known as Baburao Painter and Anandrao Painter.[5]

Indigenous camera

While in Mumbai, the brothers became avid film goers after watching Raja Harishchandra (1913), directed by Dadasaheb Phalke. On their way back to Kolhapur, they decided to make a silent film. Anandrao started working on his own indigenous camera for film making. They had bought a movie projector from a Mumbai flea market and set up Shivaji Theatre, their own movie hall in Kolhapur, thinking that if they started running a cinema, they would raise money for film production. But that did not happen and the camera remained incomplete due to Anandrao's untimely demise in 1916.[6]

Nonetheless, Baburao was determined to complete the camera. To remind him of his resolve, he kept his beard from the age of twenty three till the end of his life. Along with his disciple V. G. Damle, Baburao required two years to build the camera by doing many experiments on a lathe machine. He captured local scenes with the camera, like children jumping to swim in Rankala Lake and women washing clothes on the banks of the Panchganga River. As there was no laboratory in Kolhapur to wash the films strips, he also created the chemistry and printing machine. When he went to the theater and saw the clips, he was overjoyed to see Anandrao's dream of making an indigenous camera come true.[4]

Film career

Maharashtra Film Company

Baburao founded the Maharashtra Film Company in 1918,[7] which was set up on the site of today's Keshavrao Bhosale Natyagriha (previously the Palace Theatre). V. G. Damle, S. Fatehlal, writer Nanasaheb Sarpotdar and Baburao Pendharkar were with him at the time of establishment.[4] Later, V. Shantaram also joined the company as an apprentice.[8] Initially, Painter was short on funds to produce a movie. Shahu of Kolhapur had helped him by providing land for the studio, an electric generator and other related facilities.[9] Whereas, Tanibai Kagalkar, a well known singer at the time, also helped him by offering Rs.1000 for film production.[10]

Feature films

He chose the story of Seeta Swayamwar (Sita's wedding) for his first film as Hindu mythology was a popular theme that guaranteed viewership. But he could not find female artists to act in his film as women actors were looked down upon in conservative societies like that of Kolhapur. Without any compromise, he gave up the theme and moved on to the next film.[10]

For his next venture, Baburao managed to convince Gulab Bai (a.k.a. Kamaladevi) and Anusuya Bai (a.k.a. Sushiladevi) to act in Sairandhri, making it the first Indian film to feature women artists.[11] It was based on the mythological tale of Kichak Vadh (Slaying of Kichaka) and got censored for its graphic depiction of Bhima slaying Kichaka. The movie was released on 7 February 1920 at the Aryan theatre in Pune. When Bal Gangadhar Tilak saw the film, he was so impressed by Baburao's work that he honored him with the title Cinema Kesari and a gold medal.[10] The commercial success and positive reviews that he received from critics for this film, motivated him to take on more ambitious projects.[12]

The second silent film, Surekha Haran (1921) also benefited him financially. This was when Baburao bought the best camera of the time, manufactured by Bell & Howell. However, while filming his third silent film Markandeya, a fire broke out in the waste film stock of the company. All his film footage and the indigenous camera were gutted by fire. Only the Bell & Howell camera had survived. Sardar Nesarikar saved the studio from this crisis by providing a capital of Rs. 12,000 and thereby became a partner of the company.[13]

.jpg.webp)

In addition to mythology, Baburao also made films like Sinhagad (1923), Kalyan Khajina (1924) and Sati Padmini (1924), which were based on historical stories.[1] In 1925, he released a social film Savkari Pash (Indian Shylock) which was based on a short story by Narayan Hari Apte.[14] It showed the life of a peasant who is duped of his land by a moneylender and forced to relocate to the city in search of a job.[15][16] The film drew attention to social problems and broke the norms of conventional studio film making at the time.[17] Despite being a great silent film, it did not do well. So Baburao returned to his mainstay, the historical and mythological stories.[18]

Landmark firsts

Baburao had several landmarks in Indian film history, from building the first indigenous camera to casting first women in films.[11] He was also the first Indian filmmaker to adopt the method that Eisenstein had described as stenographic – he sketched the costumes, characters and their movements.[19] He changed the concept of set designing from painted curtains to solid three-dimensional lived in spaces and introduced artificial lighting.[20] As early as 1921–22, he understood the importance of publicity and was the first to issue booklets with details & stills of the film.[3] He also painted tasteful, eye-catching posters for his films.[21] Sairandhari (1920) was the first Indian film to face censorship by the British Government[22] whereas Savkari Pash (1925) was India's first social genre film with a focus on realism.[14][17]

Last films

The advent of sound in films did not excite Painter as he felt that they attacked the visual culture that had evolved over the years.[20] After a few more silent films, the Maharashtra Film Company pulled down its shutters in 1931. His associates V. Shantaram, V. G. Damle and S. Fatehlal had prospered under his guidance. They went on to form the Prabhat Film Company which later made several famous Marathi films.[23]

He directed talkies like Usha (1935), Savkari Pash (1936), Pratibha (1937) and Rukmini Swayamwar (1946), but they did not gain much success. Later, he was invited by V. Shantaram to direct the film Lokshahir Ram Joshi (1947) for Rajkamal Kalamandir, which Shantaram had to complete himself due to difficulties with Painter's working schedule.[24] When Baburao directed the film Vishwamitra (1952) in Mumbai, it also did not fare well. Subsequently, he retired and returned to Kolhapur. He got back to painting and sculpture, his original vocation.[13]

Select filmography

- Sairandhri (1920): An episode from the Mahabharata that dealt with the slaying of Kichaka by Bhima. It was based on the play Kichak Vadh by K. P. Khadilkar and became the first Indian film to undergo censorship.[22]

- Surekha Haran (1921): This was the debut film of V. Shantaram.[8]

- Sinhagad (1923): The film was based on Hari Narayan Apte's novel Gad Aala Pan Sinha Gela (The fort has been captured but we lost the lion). The protagonist Tanaji Malusare was a follower of Shivaji and died while capturing Sinhagad Fort. Artificial lighting used for the first time to create the effect of fog and of moonlight.[13] It also had magnificent depiction of huge crowd during the war scenes.[25]

- Kalyan Khajina (1924): This film won a medal at the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley, London.[26]

- Savkari Pash (1925): Considered to be Painter's artistic masterpiece.[27] Although, it did not bring him much commercial success.[18]

- Muraliwala (1927)

- Sati Savitri (1927)

- Usha (1935): The film (a talkie) was directed by Painter for the film company Shalini Cinetone, Kolhapur. He was also the art director of the film.[28][29]

- Remake of Savkari Pash as a talkie (1936).[30] J. B. H. Wadia on the two versions of Savkari Pash said,"I faintly remember the silent Savkari Pash... But it was only when I saw the talkie version that I realized what a great creative artist he (Baburao) was. I go into a trance when I recollect the long shot of a dreary hut photographed in low key, highlighted only by the howl of a dog."[27]

- Pratibha (1937)

- Rukmini Swayamvar (1946)

- Lokshahir Ram Joshi (1947)

- Vishwamitra (1952): Last film by Baburao Painter.[1]

Art career

Poster design

In addition to film making and directing, Baburao's artistic contributions came about in the form of artistic printed posters and banners that he created for film advertisements. The credit of introducing movie posters in the film industry goes to him, where the art of painting curtains came in handy. He made a cloth banner for the publicity of the film Sairandhri which was displayed at Aryan theatre in Pune. For the advertisement of the film Sinhagad, Baburao made huge posters that were 10 feet wide and 20 feet high. Huge crowds of spectators flocked to see these massive artistic posters. He had also advertised the movie Maya Mazaar with a giant poster of the Ghatotkacha, which was 50 feet high.[3] His poster for Kalyan Khajina (1924) is considered to be the earliest surviving image-poster of an Indian film.[31]

W. E. Gladstone Solomon, then principal of the Sir J.J. School of Art, had felicitated him for a watercolor poster of a silent film. Seeing his work, experts of the field had said that, "These magnificent artistic posters and banners are worthy of being housed in a museum where they will provide lasting value." He had also made eye-catching covers for N. S. Phadke's books like Jadugar, Daulat, Atkepar, Gujgoshti etc. These attractive covers added to the popularity of the novels and also became masterpieces in his oeuvre.[5]

Paintings

Baburao's paintings and sculptures were an integral part of his personality because at the core, he was an artist. Being a self-taught painter, he learned art by observing European paintings housed in the museums of Aundh, Vadodara and Mumbai. His paintings include portraits,[32] group compositions, mythological subjects, and a few landscapes. His artworks exhibit sound technical skills, elegance and freshness. Just like Raja Ravi Varma, his paintings have a beautiful blend of Indian subjects with western techniques. He was inclined towards the romanticism outlook of Pre-Raphaelite painters in 19th-century England.[2] Baburao's specialty was to create an imaginative image of the person in front of him with clean colors while maintaining the hues. His paintings were characterized by mild hues, dynamic lines, tonal value of the whole picture, and the delicate touch of the brush along with the combination of shapes with each other.[3] The poetic mystery created by realism is felt in his compositions. It is found that while painting the deities in human form, the unwanted parts were removed from the background so as to clearly to identify them. Some of his famous paintings were Dattatreya, Lakshmi, Saraswati, Radhakrishna, and Jalvahini to name a few.[5]

Sculptures

Baburao made sculptures using clay and bronze. He built his own casting furnace to make bronze statues. Grandeur, proportionality, elegance of the figure and craftsmanship were the hallmarks of his sculpture. He could easily make statues that were eight to ten feet tall. At times, renowned sculptor R. K. Phadke used to take his help for pouring work and also got some sculptures made from him.[33] His noted sculptures include that of Shivaji Maharaj, Mahatma Gandhi and the bust of Jyotirao Phule. Baburao continued to produce work in various art mediums till the end of his life.[18]

Personal life

Baburao married Lakshmibai in 1927 and had eight children - six daughters and two sons.[23][34]

Death and legacy

Baburao died of heart attack in Kolhapur on 16 January 1954. After his death, N. C. Phadke dedicated an entire issue of his Anjali magazine to Baburao, highlighting his all-round accomplishments in the art and film industry. In this issue, he praised Painter as Kalamaharshi (Great art sage), a title that is posthumously used with his name.[13]

A memorial to mark the establishment of Maharashtra Film Company along with the replica of the indigenous camera is erected at Khari corner in Kolhapur.[35]

In November 2002, Kalamaharshi Baburao Painter Film Society (KBPFS) was established in Kolhapur, named after the stalwart. It organizes film screenings, retrospective and film related programmes to engage film enthusiasts and inculcate a taste for good cinema.[36] The film society also organizes the Kolhapur International Film Festival and has completed eight editions in 2020.[37] As a part of the festival, the society has felicitated accomplished film makers with the Kalamaharshi Baburao Painter Award. Noted recipients of this award include Girish Kasaravalli (2015),[38] Shaji N. Karun (2016),[39] Sumitra Bhave (2017)[40] and Govind Nihalani (2019).[41]

The National Film Archive of India, Pune had organized an exhibition on Painter in June 2015 to commemorate his 125th birth anniversary. It showcased photographs, posters and publicity material of the films made by him.[42]

References

- 1 2 3 Gulzar; Govind Nihalani; Saibal Chatterjee (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema: An Enchanting Close-Up of India's Hindi Cinema. Popular Prakashan. p. 549. ISBN 978-81-7991-066-5. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- 1 2 Sadwelkar, Baburao. Doshi, Dr. Saryu (ed.). "Traditions in Art: Contemporary Art" (PDF). Marg. 36 (4): 65–80.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopaedia visual art of Maharashtra : artists of the Bombay school and art institutions (late 18th to early 21st century). Suhas Bahulkar, Pundole Art Gallery (First ed.). Mumbai. 2 March 2021. ISBN 978-81-89010-11-9. OCLC 1242719488. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 नांदगावकर, सुधीर. "मेस्त्री, बाबूराव कृष्णराव". महाराष्ट्र नायक (in Marathi). Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 Inamdar, S. D. (2013). बहुळकर, सुहास; घारे, दीपक (eds.). शिल्पकार चरित्रकोश खंड ६ - दृश्यकला [Shilpakar Charitrakosh Vol 6 - Visual Arts] (in Marathi). मुंबई: साप्ताहिक विवेक, हिंदुस्थान प्रकाशन संस्था. pp. 331–333. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ The Oxford companion to Indian theatre. Ananda Lal. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 0-19-564446-8. OCLC 56986659. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. Paul Willemen. Chicago, Ill.: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 18. ISBN 1-57958-146-3. OCLC 41960679.

- 1 2 Garga, B. D. (2005). The art of cinema : an insider's journey through fifty years of film history. New Delhi: Penguin Viking. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-670-05853-2. OCLC 68966282.

- ↑ The Oxford encyclopaedia of the music of India. Nikhil Ghosh, Saṅgīt Mahābhāratī. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-979772-1. OCLC 729238089. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 Patil, Kavita J. (2003). "Film Industry of Kolhapur: A Historical Significance". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 64: 1192–1197. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44145547. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Kalamaharshi Baburao Painter of Kolhapur was the first Indian filmmaker to cast women in his films". The Heritage Lab. 4 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ Bali, Karan (3 June 2015). "Baburao Painter". Upperstall.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 नांदगावकर, सुधीर (2014). शिल्पकार चरित्रकोश खंड ७ – चित्रपट, संगीत [Shilpakar Charitrakosh Volume 7 - Movies, Music] (in Marathi). मुंबई: साप्ताहिक विवेक, हिंदुस्थान प्रकाशन संस्था. pp. 257–261. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- 1 2 Roy, Purabi Ghosh (2003). "Cinema as Social Discourse". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 64: 1185–1191. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44145546. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ Kalidas, S., ed. (2014). Indra Dhanush : music-dance-cinema-theatre, Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-230-1951-2. OCLC 889659322.

- ↑ Nair, Paramesh Krishnan (August 1984). "India: It's never too late..." UNESCO Courier: 22–23.

- 1 2 Cousins, Mark (2004). The story of film. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-56025-612-5. OCLC 56555933.

- 1 2 3 Bhide, G.R.; Gajbar, Baba. "Kolhapur 1978". Kalamaharshi Baburao Painter (in Marathi).

- ↑ "Baburao Painter | Paintings by Baburao Painter". Saffronart. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- 1 2 "बाबूराव पेंटर (Baburao Painter )". मराठी विश्वकोश (in Marathi). 6 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ Hansa Wadkar; Shobha Shinde (1 April 2014). You Ask, I Tell: An autobiography. Zubaan. ISBN 978-93-83074-68-6. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- 1 2 "This Forgotten Pioneer Made India's First Indigenous Film Camera From Scratch!". The Better India. 15 June 2020. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- 1 2 "A Man of many arts – Baburao Painter". The Indian Express. 31 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ Kale, Pramod (1979). "Ideas, Ideals and the Market: A Study of Marathi Films". Economic and Political Weekly. 14 (35): 1511–1520. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4367902. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ↑ Valicha, Kishore (1999). The moving image : a study of Indian cinema. Bombay: Orient Longman. p. 123. ISBN 81-250-1608-2. OCLC 148086996.

- ↑ Dwyer, Rachel (2002). Cinema India : the visual culture of Hindi film. Divia Patel. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-8135-3174-8. OCLC 49518929.

- 1 2 "Savkari Pash (1925)". filmheritagefoundation.co.in. Film Heritage Foundation. 28 August 2014. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "About Studios and Stars. Shalini Cinetone: Kolhapur". The Bombay Chronicle. 3 March 1935. p. 14. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ "The Nanga Parbat conquered!". The Bombay Chronicle. 11 May 1935. p. 10. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ Ray, Bibekananda (2005). Conscience of the race : India's offbeat cinema. Edited by Naveen Joshi. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 1. ISBN 81-230-1298-5. OCLC 70208425.

- ↑ Patel, Divia (April 2013). "Indian Ink". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 23 (4): 54.

- ↑ "Mohanlal Lalji Khusalram by Painter Baburao | The Indian Portrait". Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ Mote, H. V., ed. (31 March 1993). Vishrabdh Sharada Part - 3 (in Marathi). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-8171854653. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ "Nandinee Nirmala (Painter) Raj". Daily Pilot. 16 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ "Kolhapur remembers Baburao Painter on Marathi film production foundation day | Kolhapur News - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Kalamaharshi Baburao Painter Film Society | Society Movement". kalamaharshi.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Eighth edition of Kolhapur International Film Festival to begin from March 12". ProQuest. ProQuest 2355499017. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Renowned Kannada film director Kasaravalli selected for Baburao Painter award". ProQuest. ProQuest 1748834671. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Renowned Malayalam film director Shaji Karun selected for Baburao Painter award". ProQuest. ProQuest 1850745026. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Renonwed Marathi film writer-director Sumitra". ProQuest. ProQuest 1974976792. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Govind Nihalani to get Baburao Painter award". ProQuest. ProQuest 2175764301. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ↑ "Poster exhibition at NFAI pays homage to 'Cinema Kesari' | Pune News - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

External links

- Baburao Painter at IMDb

- Documentary by DD Sahyadri (in English)

- Documentary by DD Sahyadri (in Marathi)

- Memories of Baburao Painter shared by daughter (in Marathi)