半坡 | |

Village of Banpo, reconstruction | |

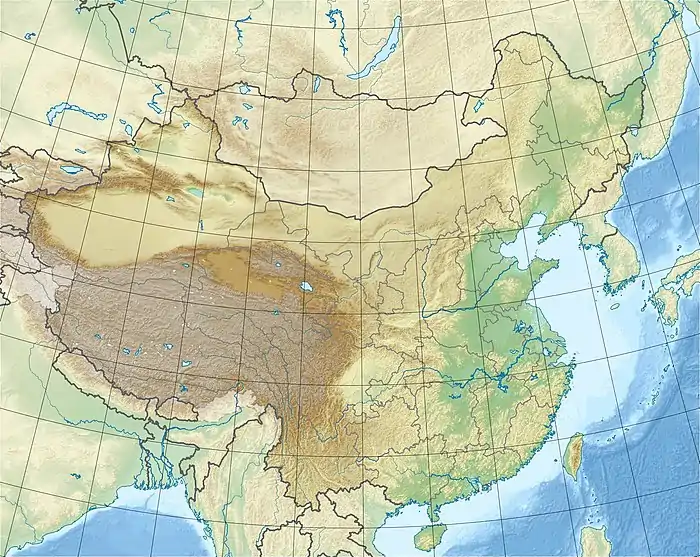

.png.webp) Location in China  Banpo (China) | |

| Location | Shaanxi |

|---|---|

| Region | China |

| Coordinates | 34°16′23″N 109°03′04″E / 34.273°N 109.051°E |

| History | |

| Founded | 4700 BCE |

| Abandoned | 3600 BCE |

| Periods | Neolithic China |

| Cultures | Yangshao culture |

Banpo is an archaeological site discovered in 1953 by Shi Xingbang,[1] and located in the Yellow River Valley just east of Xi'an, China. It contains the remains of several well organized Neolithic settlements, like Jiangzhai, carbon dated to 6700–5600 years ago (c. 4700-3600 BCE).[2][3][4][5] The area of 5 to 6 hectares (12 to 15 acres) is surrounded by a ditch, probably a defensive moat, 5 to 6 meters (16 to 20 ft) wide. The houses were circular, built of mud and wood with overhanging thatched roofs. They sat on low foundations. There appear to be communal burial areas.[6]

Banpo site

The settlement was surrounded by a moat, with the graves and pottery kilns located outside the moat perimeter. Many of the houses were semisubterranean with the floor typically 1 meter (3 ft) below the ground surface. The houses were supported by timber poles and had steeply pitched thatched roofs.

According to the Marxist paradigm of archaeology that was prevalent in the China during the time of the excavation of the site, Banpo was considered to be a matriarchal society; however, new research contradicts this claim and the Marxist paradigm is gradually being phased out in modern Chinese archaeological research.[7] Currently, little can be said of the religious or political structure from these ruins from the archaeological evidence.[6][8]

The site is now home to the Xi'an Banpo Museum, built in 1957 to preserve the archaeological collection.[9]

Banpo culture

Banpo is the type site of the Banpo culture, first phase of the Yangshao Culture. Archaeological sites with similarities to the site at Banpo are considered to be part of the “Banpo phase” (4th-3rd millennium BCE) of the Yangshao culture. Banpo was excavated from 1954 to 1957.

Pottery innovations

Banpo was the first culture to use the potter's wheel in China, while other cultures continued to use coiling techniques, and the potter's wheel only became generalized by the end of the Yangshao period.[10] Banpo also had the first pottery kilns in China.[10] The designs of the Banpo were often geometric, and animal or anthropomorphic figures.[10]

.jpg.webp) Banpo pottery kiln

Banpo pottery kiln.jpg.webp) Banpo pottery made on a potter's wheel

Banpo pottery made on a potter's wheel

Designs

.png.webp)

Banpo is known for a characteristic type of decorative pottery, with a red clay coating all over the body, and geometrical drawings in black, typically depicting a round human head with some fish around it. The round human head had a triangular design on top.[11] Similarities have been noted between the motifs of the Afanasievo culture and Okunev culture of the Minusinsk basin in Siberia, and those on the potteries of Banpo.[12] Pottery style emerging from the Yangshao culture spread westward to the Majiayao culture, and then further to Xinjiang and Central Asia.[13]

Several of the potteries have symbol marks, and are part of the Neolithic signs in China, but each sign occurs singly, which is antinomic with the function of a written script. They could instead be the personal mark of individual potters.

._Found_in_Shaanxi_province._Beijing_Capital_Museum.jpg.webp) Pottery pot with human and fish design, Shaanxi province. Beijing Capital Museum

Pottery pot with human and fish design, Shaanxi province. Beijing Capital Museum Human faced–fish decorated bowl recovered at Banpo.

Human faced–fish decorated bowl recovered at Banpo. Banpo anthropomorphic motif

Banpo anthropomorphic motif Banpo burial

Banpo burial A skull recovered at Banpo displayed at the Xi'an Banpo Museum.

A skull recovered at Banpo displayed at the Xi'an Banpo Museum. Banpo pottery symbols

Banpo pottery symbols

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "Pioneering archaeologist who helped excavate Terracotta Warriors dies at 99". South China Morning Post. 24 October 2022.

- ↑ Yang, Xiaoping (2010). "Climate Change and Desertification with Special Reference to the Cases in China". Changing Climates, Earth Systems and Society. pp. 177–187. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8716-4_8. ISBN 978-90-481-8715-7.

- ↑ Crawford, Garry W. (2004). "East Asian plant domestication" (PDF). In Miriam T. Stark (ed.). Archaeology of Asia. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 77–95.

- ↑ Fuller, Dorian Q; Qin, Ling; Harvey, Emma (2008). "A Critical Assessment of Early Agriculture in East Asia, with emphasis on Lower Yangzte Rice Domestication" (PDF). Pragdhara: 17–52.

- ↑ Meng, Y; Zhang, HQ; Pan, F; He, ZD; Shao, JL; Ding, Y (2011). "Prevalence of dental caries and tooth wear in a Neolithic population (6700-5600 years BP) from northern China". Archives of Oral Biology. 56 (11): 1424–35. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.04.003. PMID 21592462.

- 1 2 Jarzombek, Mark M; Prakash, Vikramaditya (9 February 2011). A Global History of Architecture. Wiley. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9780470902455.

- ↑ Liu, Li (2004). The Chinese Neolithic. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781139441704.

- ↑ Lu, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.-b.; Wu, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, K.; Ye, M.; Zhang, T.; et al. (2009). "Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (18): 7367–72. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.7367L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900158106. PMC 2678631. PMID 19383791.

- ↑ "Banpo Museum in Xi'an". chinamuseums.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Chang, Kwang-chih; Xu, Pingfang; Lu, Liancheng; Pingfang, Xu; Wangping, Shao; Zhongpei, Zhang; Renxiang, Wang (1 January 2005). The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-300-09382-7.

- ↑ Fang, Lili (3 March 2011). Chinese Ceramics. Cambridge University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-521-18648-3.

- ↑ Kiselov (Киселёв), С.В. (1962). Study of the Minusinsk stone sculptures (К изучению минусинских каменных изваяний). Historical and archaeological collection ( Историко-археологический сборник). pp. 53–61.

During the excavations of the world-famous Yanshao [Yangshao] culture site near the village of Banpo near Xi'an, among numerous painted vessels, two large open bowls with paintings were found, especially important for comparison with images of masks from the Minusinsk-Khakass basin. Inside these bowls are painted masks that are strikingly similar to Minusinsk ones. They are distinguished by a horizontal division of the face into three zones, the presence of horns and a triangular figure above the head, as well as triangles on the chin (Fig. 2 ). Such coincidences can hardly be explained by mere chance. Even a few years before the discoveries in Ban-po, I had to pay attention to a number of features that bring the Eneolithic Afanasiev culture of the middle Yenisei closer to the culture of painted ceramics of Northern China. Apparently, the finds in Ban-po once again confirm these observations. At the same time, the noted finds and comparisons show that the appearance of images, so characteristic of the ancient stone sculptures of the middle Yenisei, not only goes back to the deep antiquity of the pre-Afanasiev time, but is apparently associated with the complex world of symbolic images of the Far East, now known from monuments of the Neolithic of Ancient China.

- ↑ Zhang, Kai (4 February 2021). "The Spread and Integration of Painted pottery Art along the Silk Road". Region - Educational Research and Reviews. 3 (1): 18. doi:10.32629/RERR.V3I1.242. S2CID 234007445.

The early cultural exchanges between the East and the West are mainly reflected in several aspects: first, in the late Neolithic period of painted pottery culture, the Yangshao culture (5000-3000 BC) from the Central Plains spreadwestward, which had a great impact on Majiayao culture (3000-2000 BC), and then continued to spread to Xinjiang and Central Asia through the transition of Hexi corridor

References

- Allan, Sarah (ed), The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective, ISBN 0-300-09382-9

- Chang, Kwang-chih. The Archaeology of Ancient China, ISBN 0-300-03784-8