| Battle of Kirkuk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman–Persian War (1730–35) and Nader's Campaigns | |||||||||

Illustration showing the final phases and near end of the battle, where Nader stares despondently at the corpse of Topal Pasha, the only man who had ever defeated him in battle. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Nader Haji Beg Khan |

Topal Osman Pasha † Memish Pasha † | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Slightly less than the Ottomans[3] | ~100,000[4] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| minimal[5] |

20,000[6]

| ||||||||

The Battle of Kirkuk (Persian: نبرد کرکوک), also known as the Battle of Agh-Darband (Persian: نبرد آقدربند), was the last battle in Nader Shah's Mesopotamian campaign where he avenged his earlier defeat at the hands of the Ottoman general Topal Osman Pasha, in which Nader achieved suitable revenge after defeating and killing him at the battle of Kirkuk. The battle was another in the chain of seemingly unpredictable triumphs and tragedies for both sides as the war swung wildly from the favour of one side to the other. Although the battle ended in a crushing victory for the Persians, they had to be withdrawn from the area due to a growing rebellion in the south of Persia led by Mohammad Khan Baluch. This rebellion in effect robbed Nader of the strategic benefits of his great victory which would have included the capture of Baghdad, if he had the chance to resume his campaign.

Background

The defeat Nader had conceded at the Battle of Samara had effects beyond just the immediate results of reducing Nader's force by 30,000 and saving Baghdad from his clutches. The loss of so many experienced fighting men and precious equipment could not be easily overcome and the first task Nader faced was restoring the morale of his fighting men who had up to that point thought themselves invincible, and not without reason as they had been nothing but victorious in all encounters. Summoning his officers he began with admitting his own mistakes: "...[Nader] claimed his fate and those of him men as one and the same, reminding them of their past sacrifices and bravery, promised them that he would wipe away the memory of their recent defeat. Thus, he came to be admired by his officers and soldiers alike and while instilling a renewed fighting spirit in the souls of his warriors he ensured they would not show reluctance in the forthcoming conclusion with the Turks."

A rebellion broke out in southern Persia under the leadership of Mohammad Khan Baluch who gathered a substantial mass of malcontents around himself and was supplied with more men from the local Arab tribes in the region. Nader's solution was first to rectify the problem of Topal Pasha and only then crush Mohammad Khan's rebellion.

There were also political dimensions present as Nader was keen to rectify his reputation as news of his defeat at Samarra would spread in Persia making fertile soil for any growths of rebellion from within. It is unclear to what extent Nader craved an opportunity to repair his ego as well as his reputation by defeating Topal Pasha who was the only man (and would remain the only man) to have bested him on the field of battle. Nader set about rapidly rebuilding his army for another confrontation with the victorious Topal Pasha.

Topal Pasha was also eager to make good his losses having suffered the total loss of 20,000 men or 1 out of every 4 in his army. Sending requests to Istanbul he also demanded to be replaced with a younger general (Topal Pasha was approximately 70 years old at this time). By the time of the next Persian invasion of Iraq however he managed to put together an army 100,000 strong.

The battle

The opening phase

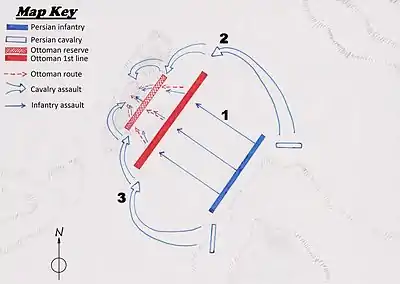

Nader's spies informed him of a 12,000 strong force approaching via the valley of Agh-Darband. Topal Pasha had dispatched this body of men under Memish Pasha as an advance guard with himself following up with the main army. Nader also sent out an advance guard under Haji Beg Khan in order to lure the Memish Pasha towards the main Persian army. After pursuing Haji Beg for a distance Memish Pasha marched right into the jaws of Nader's ambush with two sets of 15,000 men setting upon the Ottomans from two directions and routing them with ease. Memish Pasha, who had sent word to Topal Osman Pasha claiming to have routed the Persian and requesting further troops for the pursuit, now lay amongst the dead.

The rout of Memish Pasha's soldiers was followed up by a rapid advance by Nader with the bulk of his army against the main Ottoman force under Topal Pasha who was a mere 5 kilometres away. Topal Pasha sensing something was afoot ordered a halt and began to deploy his men. As the Persian army closed the distance Nader formed up his infantry body in a line and sent it forward to engage the janissaries. A violent enfilade commenced, in which the Ottoman and Persian soldiery raked fire upon each other for two hours.

2. Nader sends Haji Beg Khan around the Ottoman left with 15,000 cavalry

3. Nader flanks the Ottoman right with another 15,000 cavalry, thereby completing the Envelopment of the Ottomans.

The closing phase

The Persian Jazāyerchi, after two hours of continuous musketry directly charged into the janissaries ranks. With impeccable timing Nader now released two contingents of cavalry, each 15,000 strong with Haji Beg in command of the right and himself in command of the left contingent, he manoeuvred around the Ottoman line and caught it in a double-envelopment.[8]

The Ottomans were now pressed by a vicious assault of sabre-armed Jazāyerchi from ahead as well as two bodies of cavalry slicing into their formations from either flank. As the Janissaries began to collapse and were chased from their positions the jazayerchi started to fire into their backs. The situation was so dire that Topal Pasha recognized his sad fate and mounted a horse to join his men in what would be his last battle. The old fox had been outwitted by the young Afshar who he had all too recently bested at Samara, but Topal Osman chose to die with his men rather than fall back and escape with his life. The old general was shot twice before he fell from his mount whence a Persian cavalryman severed his head from his body, taking the gory item to present to Nader.

The battle ended with some 20,000 Ottoman casualties in addition to the loss of all their artillery as well as most of their baggage. Sufficient vengeance for the terrible defeat Topal Pasha had inflicted on Nader at Samara. Nader in respect of Topal Osman Pasha's person ordered his head to be reunited with his body, for a while he stared despondently at the frail old corpse of the only man who had defeated him in battle, perhaps disconcerted by the fact that such a frail old man had battled him harder than any other of his younger adversaries. Along with full honours, Nader sent the body of Topal Osman Pasha to Baghdad where he was to be buried.

Aftermath

Nader had been hopeful of starting a new siege of Baghdad and began to put together the logistics of its capture as well as preparing for a campaign in the Caucasus. Startled by Topal Pasha's defeat and death, Ahmad Pasha began negotiations to hand over territory in exchange for peace though these were never ratified by Istanbul. Tabriz had already been evacuated by the Ottomans in the aftermath of the panic which the battle of Kirkuk caused, but repeated reports of Mohammad Khan's rebellion in the south of Iran could not be ignored any longer as the uprising started to turn into a more serious threat. This robbed Nader of all the potential strategic fruits of his victory as he was finally poised to take Baghdad, but had to gather his troops to march back into the interior of the Empire to put down Mohammad Khan's rebellion back in Persia.

In many ways however, the overall victor of the Mesopotamian campaign was Topal Osman who saved Baghdad due to his crushing victory in the battle of Samarra and although he was later defeated and killed at Kirkuk (Agh-Darband), Nader could not exploit his victory at that time due to Mohammad Khan Baluch's insurrection back in Persia. If Topal Osman Pasha had lost at Samarra then Baghdad would certainly have fallen into Persian hands and probably remained under Persian rule for at least decades to come.

See also

References

- ↑ Lockhart, Laurence, Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly Upon Contemporary Sources, London, 1938, p. 77. Luzac & Co.

- ↑ Ghafouri, Ali(2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now,p. 382. Etela'at Publishing

- ↑ Axworthy, Michael(2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant,p. 141, I. B. Tauris

- ↑ Axworthy, Michael(2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant,p. 141, I. B. Tauris

- ↑ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein(2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah,p. 47. Donyaye Ketab

- ↑ Axworthy, Michael(2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant,p. 190. I. B. Tauris

- ↑ Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein(2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah,p. 46. Donyaye Ketab

- ↑ Ghafouri, Ali(2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now,p. 382. Etela'at Publishing

Sources

- Moghtader, Gholam-Hussein(2008). The Great Batlles of Nader Shah, Donyaye Ketab

- Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, I. B. Tauris

- Ghafouri, Ali(2008). History of Iran's wars: from the Medes to now, Etela'at Publishing

- GÜNHAN BÖREKÇİ(2006). A_Contribution_to_the_Military_Revolution_Debate_The_Janissaries_Use_of_Volley_Fire__1593, Department of History, Ohio University