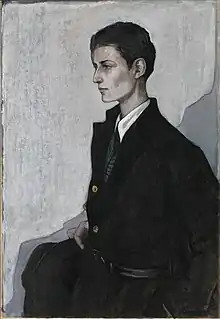

Romaine Brooks | |

|---|---|

Romaine Brooks, circa 1894 | |

| Born | Beatrice Romaine Goddard May 1, 1874 |

| Died | December 7, 1970 (aged 96) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, portraiture |

| Movement | Symbolist, aesthetic |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Natalie Clifford Barney |

Romaine Brooks (born Beatrice Romaine Goddard; May 1, 1874 – December 7, 1970) was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portraiture and used a subdued tonal palette keyed to the color gray. Brooks ignored contemporary artistic trends such as Cubism and Fauvism, drawing on her own original aesthetic inspired by the works of Charles Conder, Walter Sickert, and James McNeill Whistler. Her subjects ranged from anonymous models to titled aristocrats. She is best known for her images of women in androgynous or masculine dress, including her self-portrait of 1923, which is her most widely reproduced work.[1]

Although her family was wealthy,[2] Brooks had an unhappy childhood after her alcoholic father abandoned the family; her mother was emotionally abusive and her brother mentally ill. By her own account, her childhood cast a shadow over her whole life. She spent several years in Italy and France as a poor art student, then inherited a fortune upon her mother's death in 1902. Wealth gave her the freedom to choose her own subjects. She often painted people close to her, such as the Italian writer and politician Gabriele D'Annunzio, the Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein, and her partner of more than 50 years, the writer Natalie Barney.

Although she lived until 1970, it is erroneously believed that she painted very little after 1925 despite evidence to the contrary.[3] She made a series of drawings during the 1930s, using an "unpremeditated" techniques predating automatic drawing. She spent time in New York City in the mid 1930s, completing portraits of Carl Van Vechten and Muriel Draper. Many of her works are unaccounted for, but photographic reproductions attest to her ongoing artwork. It is thought to have culminated in her 1961 portrait of Duke Uberto Strozzi.[3]

Life and career

Early life and education

Beatrice Romaine Goddard was born in Rome, the youngest of three children of the wealthy American Ella (Waterman) Goddard and her husband Major Henry Goddard who was also American.[4] Her maternal grandfather was the coal mining multi-millionaire Isaac S. Waterman Jr. Her parents divorced when she was small, and her father abandoned the family. Beatrice was raised in New York by her unstable mother, who abused her emotionally while doting on her mentally ill brother, St. Mar.[4] According to one source, Goddard had to tend to St. Mar, because he attacked anyone else who came near him. According to her memoir, when she was seven, her mother fostered her to a poor family living in a New York City tenement, then disappeared and stopped making the agreed-upon payments. The family continued to care for Beatrice, although they sank further into poverty. She did not tell them where her grandfather lived for fear of being returned to her mother. Other sources record that she attended a girls' school in New Jersey, an Italian convent and a Swiss finishing school.[4]

After the foster family located her grandfather, he arranged to send Beatrice to study for several years at St. Mary's Hall[5] (now Doane Academy) an Episcopal girls boarding school in Burlington, New Jersey. Later, she attended a convent school, in between times spent with her mother, who moved around Europe constantly, although the stress of travel made St. Mar harder to control.[6] In adulthood, Goddard Brooks referred to herself as having been a "child-martyr".[7]

In 1893 at the age of 19, Goddard left her family and went to Paris.[4] She extracted a meager allowance from her mother, took voice lessons, and for a time sang in a cabaret, before finding out she was pregnant and delivering a baby girl on February 17, 1897. She placed the infant in a convent for care, then travelled to Rome to study art.[8] Goddard was the only female student in her life class, as it was unusual for women to work from nude models. She encountered what now would be called sexual harassment. When a fellow student left a book open on her stool with pornographic passages underlined, she picked it up and hit him in the face with it, but he and his friends stalked her. She fled to Capri after he tried to force her to marry him.[9]

In the summer of 1899, Goddard rented a studio in the poorest part of the island of Capri. Despite her best efforts, her funds were still insufficient. After several months of near starvation, she suffered a physical breakdown. In 1901, she returned to New York when her brother St. Mar died; with her grief-stricken mother dying less than a year later from diabetes complications. Goddard was 28 when she and her sister inherited the large estate their Waterman grandfather had left, which made them independently wealthy.[10]

Personal life

Despite being a lesbian, on June 13, 1903, Goddard married her friend John Ellingham Brooks and acquired British nationality.[4] Brooks was an unsuccessful pianist and translator who was in deep financial difficulty. He was homosexual as well, and Goddard never revealed exactly why she married him. Her first biographer Meryle Secrest suggests that she was motivated by concern for him and a desire for companionship, rather than the need for a marriage of convenience. They quarreled almost immediately when she cut her hair and ordered men's clothes for a planned walking tour of England; he refused to be seen in public with her dressed that way. Chafing at his desire for outward propriety, she left him after only a year and moved to London. His repeated references to "our" money frightened her, as the money was her inheritance and none of it his.[11] After they split, she continued to give Brooks an allowance of 300 pounds per year. He lived comfortably on Capri, with E.F. Benson,[12] until he died of liver cancer in 1929.[13]

Career

In 1904, Brooks became dissatisfied with her work, and in particular with the bright color schemes that she had used in her early paintings. She travelled to St. Ives on the Cornish coast, rented a small studio, and began learning to create finer gradations of gray. When a group of local artists asked her to give an informal show of her work, she displayed only some pieces of cardboard on which she had dabbed her experiments with gray paint. From then on, nearly all of her paintings are keyed to a gray, white and black color scheme with touches and tints of ochre, umber, alizarin and teal. By 1905, she had found her tonal palette, and would continue to develop these harmonics her whole career.[3][14]

First exhibition

Brooks left St. Ives and moved to Paris. Poor young painters such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were creating new art in the Bohemian districts of Montparnasse and Montmartre. In contrast, Brooks took an apartment in the fashionable 16th arrondissement, mingled in elite social circles, and painted portraits of wealthy and titled women. These included her current lover, the Princess de Polignac.

In 1910, Brooks had her first solo show at the prestigious Gallery Durand-Ruel, displaying thirteen paintings, almost all of women or young girls. Some were portraits; others showed anonymous models in interior scenes or against tonal backgrounds, often with pensive or withdrawn expressions. The paintings were generally naturalistic, showing an attentive eye for the details of Belle Époque fashion, with parasols, veils, and elaborate bonnets on display.[15]

Brooks included two nude studies in this first exhibition—a provocative choice for a woman artist in 1910. In The Red Jacket, a young woman stands in front of a large folding screen, wearing only a small open jacket, with her hands behind her back. Her emaciated stature and forlorn expression led one contemporary reviewer to refer to her as a consumptive; Brooks described her simply as "a poor girl who was cold". The other, White Azaleas, is a more sexually charged nude study of a woman reclining on a couch. Contemporary reviews compared it to Francisco de Goya's La maja desnuda and Édouard Manet's Olympia. Unlike the women in those paintings, the subject of White Azaleas looks away from the viewer; in the background above her is a series of Japanese prints which Brooks loved.[16]

The exhibition established Brooks' reputation as an artist. Reviews were effusive, and the poet Robert de Montesquiou wrote an appreciation calling her "the thief of souls." The restrained, almost monochromatic decor of her home also attracted attention; she was often asked to give advice on interior design, and sometimes did, though she did not relish the role of decorator. Brooks became increasingly disillusioned with Parisian high society, finding the conversation dull, and feeling that people were whispering about her.[17] Despite her artistic success, she described herself as a lapidée—literally, a victim of stoning.[18][19]

Gabriele D'Annunzio and Ida Rubinstein

In 1909, Brooks met Gabriele D'Annunzio, an Italian writer and politician who had come to France to escape his debts. She saw him as a martyred artist, another lapidé; he wrote poems based on her works and called her "the most profound and wise orchestrator of grays in modern painting".[20]

In 1911, Brooks became romantically involved with the Ukrainian-Jewish actress and dancer Ida Rubinstein. Rubenstein was a tremendous celebrity of her day and caused quite a stir by appearing with Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.[3] D'Annunzio had an obsessive but unrequited attraction to Rubinstein as well.[21] Rubinstein was deeply in love with Brooks; she wanted to buy a farm in the country where they could live together—a mode of life in which Brooks had no interest.[22]

Although they broke up in 1914, Brooks painted Rubinstein more often than any other subject; for Brooks, Rubinstein's "fragile and androgynous beauty"[23] represented an aesthetic ideal. The earliest of these paintings are a series of allegorical nudes. In The Crossing (also exhibited as The Dead Woman), Rubinstein appears to be in a coma, stretched out on a white bed or bier against a black void variously interpreted as death or floating in spent sexual satisfaction on Brooks' symbolic wing;[3] in Spring, she is depicted as a pagan Madonna strewing flowers on the ground in a grassy meadow. When Rubinstein starred in D'Annunzio's play The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, Brooks painted her as a blonde Saint Sebastian—tied to a post, being shot with an arrow by a masked dwarf standing on a table. The dwarf is a satiric representation of D'Annunzio.[3][24]

At the beginning of World War I, Brooks painted The Cross of France, a symbolic image of France at war, showing a Red Cross nurse looking off to the side with a resolute expression while Ypres burns in the distance behind her. Although it is not a portrait of Rubinstein, it does resemble her, and she may have modelled for it. It was exhibited along with a poem by D'Annunzio calling for courage and resolution in wartime, and later reproduced in a booklet sold to raise funds for the Red Cross.[25] After the war, Brooks received the cross of the Legion of Honor for her fundraising efforts.

The political imagery of The Cross of France has been compared to Eugène Delacroix's painting Liberty Leading the People, in which a woman personifying Liberty holds up a flag against the background of a burning city.[25] Delacroix's Liberty leads a group of Parisians who have taken up arms, while the subject of The Cross of France stands alone. Brooks used this romantic image of a figure in heroic isolation in both the 1912 portrait of D'Annunzio and her 1914 self-portrait; the subjects are wrapped in dark cloaks and isolated against seascapes.[26]

During the war, D'Annunzio became a national hero as leader of a fighter squadron. During the Paris Peace Conference, he led a group of nationalist irregulars who seized and held the city of Fiume to prevent Italy from ceding it to Croatia. He briefly set up a government, the Italian Regency of Carnaro, with himself as Duce. He was never part of Benito Mussolini's government. Although he is regarded as a precursor of Fascism, D'Annunzio disavowed any connection with Mussolini or Fascism toward the end of his life.

The details of Brooks's own conservative politics have been clouded by her friendship with D'Annunzio, and admiration of him as an artist and fellow sufferer. There is no evidence that she was a card-carrying Fascist or that she was sympathetic to Italian Fascism. The classicizing individualism of her paintings may have been influenced by D'Annunzio's aesthetics—an idea that has troubled some viewers otherwise attracted to the imagery of Brooks's portraits.[3][27]

On June 16, 2016, under the direction of Dr. Langer and Legion Group Arts, young Italian researcher Giovanni Rapazzini de Buzzaccarini discovered a long-lost early work by Brooks at the Vittoriale in Gardone. Brooks had copied (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci 1450–1523) Perugino's Portrait of a Young Man at the Uffizi when she was a penniless art student in Rome. She painted the man because she thought he resembled herself as a girl. She later gave the painting to D'Annunzio as a joke when she refused to become his lover. D'Annunzio was in the tasteless habit—Romaine thought—of hanging pictures of his mistresses in a rogue's gallery. Buzzaccarini found this painting in the music room.

D'Annunzio and Brooks had spent the summer of 1910 in a villa on the coast of France until D'Annunzio was disrupted by one of his jealous ex-mistresses. She came to the gates of Brooks' villa with pistol in hand, demanding entry.[26] After a brief falling out, Romaine resumed a friendship with D'Annunzio that lasted until his death in Gardone Riviera, Italy.[28]

Brooks painted Rubinstein one last time in The Weeping Venus (1916–1917), a nude based on a photographs that Brooks took during their relationship; she needed them because Rubinstein was such a restless and unreliable model. According to Brooks' unpublished memoir, the painting represents "the passing away of familiar gods" as a result of World War I. She said she tried to repaint Venus's features many times, but Rubinstein's face somehow kept returning: "It fixes itself in the mind."[29]

Natalie Barney and Left Bank portraits

The longest and most important relationship of Brooks' life was her three-way partnership with Natalie Clifford Barney, an American-born writer, and Lily de Gramont, a French aristocrat. She formed a trio with them that lasted the rest of their lives.

Barney was notoriously non-monogamous, a fact that the other two women had to accept. Brooks met Barney in 1916, at a time when the writer had already been involved for about seven years with Duchess Elisabeth de Gramont, also known as Lily or Elisabeth de Clermont-Tonnerre. She was married and the mother of two daughters. After a brief dust-up that resulted in Barney's offering Gramont a marriage contract while at the same time refusing to give up Brooks, the three women formed a stable lifelong triangle in which none was a third wheel. Gramont, one of the most glamorous taste-makers and aristocrats of the period, summed up their values when she said, "Civilized beings are those who know how to take more from life than others."[3] Gender fluidity and sexual freedom were paramount among women of Brooks' circle. Barney hosted a literary salon on Paris's Left Bank.

Brooks tolerated Barney's casual affairs well enough to tease her about them, and had a few of her own over the years. She could become jealous when a new love became serious. Usually she simply left town, but at one point she gave Barney an ultimatum to choose between her and Dolly Wilde—relenting once Barney had given in.[30] At the same time, while Brooks was devoted to Barney, she did not want to live with her full-time. She disliked Paris, disdained Barney's friends, and hated the constant socializing on which Barney thrived. She felt most fully herself when alone.[31] To accommodate Brooks's need for solitude, the women built a summer home consisting of two separate wings joined by a dining-room, which they called Villa Trait d'Union, the "hyphenated villa". Brooks spent part of each year in Italy or traveling elsewhere in Europe, away from Barney.[32] The relationship lasted for more than 50 years.

Brooks's portrait of Barney has a softer look than her other paintings of the 1920s. Barney sits, swathed in a fur coat, in the house at 20 Rue Jacob where she lived and held her salon. In the window behind her, the courtyard is seen dusted with snow. Brooks often included animals or models of animals in her compositions to represent the personalities of her sitters;[33] she painted Barney with a small sculpture of a horse, alluding to the love of riding that had led Remy de Gourmont to nickname her "the Amazon". The paper on which the horse stands may be one of Barney's manuscripts.[34]

From 1920 to 1924, most of Brooks's subjects were women who were in Barney's social circle or who visited her salon. Truman Capote, who toured Brooks's studio in the late 1940s, may have been exaggerating when he called it "the all-time ultimate gallery of all the famous dykes from 1880 to 1935 or thereabouts",[35] but Brooks painted many of them. Barney's lover of the moment was Eyre de Lanux; her own lover Renata Borgatti; Una, Lady Troubridge, the partner of Radclyffe Hall; and the artist Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein). Another of Brooks' lovers was the wildly eccentric Marchesa Luisa Casati, whose portrait she painted in 1920 while on Capri.[36]

Several of these paintings depict women who had adopted some elements of male dress. While in 1903, Brooks had shocked her husband by cutting her hair short and ordering a suit of men's clothes from a tailor, by the mid-1920s bobbed and cropped hairstyles were "in" for women and wearing tailored jackets—usually with a skirt—was a recognized fashion, discussed in magazines as the "severely masculine" look.[37] Women such as Gluck, Troubridge, and Brooks used variations of the masculine mode, not to pass as men, but as a signal—a way of making their sexuality visible to others. At the time these paintings were made, however, it was a code that only a select few knew how to read.[38] To a mainstream audience, the women in these paintings probably just looked fashionable.

Gluck, an English artist whom Brooks painted around 1923, was noted in the contemporary press as much for her style of dress as for her art. She pushed the masculine style further than most by wearing trousers on all occasions, which was not considered acceptable in the 1920s. Articles about her presented her cross-dressing as an artistic eccentricity or as a sign that she was ultra-modern.[39] Brooks' portrait shows Gluck in a starched white shirt, a silk tie, and a long black belted coat that she designed and had made by a "mad dressmaker";[40] her right hand, at her waist, holds a man's hat. Brooks painted these masculine accoutrements with the same attention she had once given to the parasols and ostrich plumes of La Belle Époque. However, while many of Brooks' early paintings show sad and withdrawn figures "consumed by petticoats, veiled hats and other period trappings of femininity",[41] Gluck is self-possessed and quietly intense—an artist who insists on being taken seriously.[42] Her appearance is so androgynous that it would be difficult to identify her as a woman without help from the title, and the title itself—Peter, a Young English Girl—underscores the gender ambiguity of the image.[43]

Brooks's 1923 self-portrait has a somber tone. Brooks—who also designed her own clothes[44]—painted herself in a tailored riding coat, gloves, and top hat. Behind her is a ruined building rendered in gray and black, underneath a slate-colored sky. The only spots of strong color are her lipstick and the red ribbon of the Legion of Honor that she wears on her lapel, recalling the Red Cross insignia in The Cross of France.[45] Her eyes are shaded by the brim of her hat, so that, according to one critic, "she's watching you before you get close enough to look at her. She's not passively inviting your approach; she's deciding whether you're worth bothering with."[46]

Literary portraits of Brooks

In 1925, Brooks had solo exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York. There is no evidence to substantiate the claim that Brooks ceased painting after 1925. While in New York during the '30s, she produced portraits of Carl Van Vechten in 1936 Muriel Draper in 1938 that we know of. We know that she purchased paints in WWII when she and Natalie were trapped in Florence. As researchers, we know from photographs that there are lost works by Brooks still to be rediscovered.[3] After that year, she produced only four more paintings, including portraits of Carl Van Vechten in 1936 and Muriel Draper in 1938.[47] Moreover, Brooks did complete what previous scholars thought to be her last portrait at the age of 87 in 1961. The artist stated that she had drawn all her life so there is no reason to assume she was not doing so by the time MacAvoy painted her portrait. In fact, she herself says in her audio interview from 1968 that she was miffed by the fact that McAvoy portrait of her showed a bunch of dried up brushes rather than the glass table she used as a palette "As if I didn't paint." Her comments seem to indicate she was anything but dried up as a painter. In fact, she had intended to paint a portrait of MacAvoy but he never had time to sit for her. During the '30s, she became the subject of literary portraits by three writers. Each portrayed her as part of lesbian social circles in Paris and Capri.

Brooks was the model for the painter Venetia Ford in Radclyffe Hall's first novel The Forge (1924). The protagonist Susan Brent first encounters Ford among a group of women at a masquerade ball in Paris; the descriptions of these women correspond closely to Brooks's portraits, particularly those of Elisabeth de Gramont and Una Troubridge. Brent decides to leave her husband and pursue art after seeing the painting The Weeping Venus.[48] Brooks also appeared in Compton Mackenzie's Extraordinary Women (1928), a novel about a group of lesbians on Capri during World War I, as the composer Olympia Leigh. Although the novel is satirical, Mackenzie treats Brooks with more dignity than the rest of the characters, portraying her as a detached observer of the others' jealous intrigues—even those of which she is the focus.[49] In Djuna Barnes's Ladies Almanack (1928), a roman à clef of Natalie Barney's circle in Paris, she makes a brief appearance as Cynic Sal, who "dresse[s] like a coachman of the period of Pecksniff"[50]—a reference to the style of dress seen in her 1923 self-portrait.

Drawings and later life

From the 1930s onward, her work was largely forgotten.[51] In 1930, while laid up with a sprained leg, Brooks began a series of more than 100 drawings of humans, angels, demons, animals, and monsters, all formed out of continuous curved lines. She said that when she started a line she did not know where it would go, and that the drawings "evolve [d] from the subconscious...[w]ithout premeditation."[52] Brooks was writing her unpublished memoir No Pleasant Memories at the same time she began this series of drawings. Critics have interpreted them as exploring the continuing effect of her childhood on her—a theme expressed even in the symbol she used to sign them, a wing on a spring.[53] Decades later, at 85, she said, "My dead mother gets between me and life."[54]

.jpg.webp)

Brooks is thought to have stopped painting by several writers, but she herself tells us that she drew all her life. She moved from Paris to Villa Sant'Agnese, a villa outside Florence, Italy in 1937, and in 1940—fleeing the invasion of France by Germany—Barney joined her there.[55] After World War II ended, Brooks declined to move back to Paris with Barney, saying she wanted to "get back to [her] painting and painter's life",[56] but in fact she virtually abandoned art after the war.[57] She and Barney were involved in promoting her work and arranging gallery and museum placements for her paintings.[58] She became increasingly reclusive, and while Barney continued to visit her frequently, by the mid-1950s she had to stay in a hotel, meeting Brooks only for lunch.[59] Brooks spent weeks at a time in a darkened room, believing she was losing her eyesight.[60] According to Secrest, she became paranoid, fearing that someone was stealing her drawings and that her chauffeur planned to poison her. However, subsequent research (Langer) leads researchers to believe her fears were not unfounded. In a 1965 letter, she cautioned Barney not to lie down on the benches in her garden, lest the plants feed on her life force: "Trees especially are our enemies and would suck us dry."[61] In the last year of her life, she stopped communicating with Barney entirely, leaving letters unanswered and refusing to open the door when Barney came to visit.[62] Her reasons for doing so are referenced in Langer's biography. She died in Nice, France in 1970 at the age of 96. Brooks is buried in the old English Cemetery in Nice, in a family plot with her mother and her brother St. Mar.[63]

Influences

Brooks kept aloof from the artistic trends and movements of her time, "act[ing] as if the Fauvists, the Cubists, and the Abstract Expressionists did not exist."[64] However, some critics have mistakenly said Brooks was influenced by Aubrey Beardsley's illustrations, a claim Brooks herself refutes in her 1968 audio interview. The imagery of the 1930s drawings continues Brooks's experiments in the Surreal that she began as a teenager in the late 1880s. Her use of "premeditated" drawings as a route to the subconscious has been compared to automatic drawings by the Surrealists of the 1920s, but Brooks's work predates Surrealists such as André Masson by decades. MacAvoy called her the first Surrealist.[3][8]

The most widely observed influence on Brooks's painting is that of James McNeill Whistler, whose subdued palette probably inspired her to adopt a monotone color scheme with accents of tinted pigments because through this technique she could suggest a classical restraint and create tensions that were modulated by shape, texture, and variations of shading throughout her canvases. She may have been introduced to Whistler's work by the art collector Charles Lang Freer, whom she met on Capri around 1899, and who bought one of her early works.[65] Brooks said she "wondered at the magic subtlety of [Whistler's] tones" but thought his 'symphonies' lacked the corresponding subtlety of expression.[66] One 1920 portrait may take its composition from a painting by Whistler. While the poses are almost identical, Brooks removes the little girl and all the details of Whistler's domestic scene, leaving only Borgatti and her piano—an image of an artist completely focused on her art.[67]

Legacy and modern criticism

Brooks's realistic style may have led many art critics to dismiss her, and by the 1960s her work was largely forgotten.[68] The revival of figurative painting since the 1980s, and new interest in the exploration of gender and sexuality through art, have led to a reassessment of her work. She is now seen as a precursor of present-day artists whose works depict gender variance and transgender themes.[69] Critics have described her portraits of the 1920s as a "sly celebration of gender-bending as a kind of heroic act"[41] and as creating "the first visible Sapphic stars in the history of modernism."[44]

Brooks's portraits starting with her 1914 self-portrait extending through The Cross of France have been interpreted as creating new images of strong women. The portraits of the 1920s in particular—cross-dressed and otherwise—portray their subjects as powerful, self-confident, and fearless.[70] One critic compared them to the faces on Mount Rushmore.[71] Brooks seems to have seen her portraits in this light. According to a memoir by Natalie Barney, one woman complained, upon seeing her portrait, "You haven't beautified me", to which Brooks replied "I have ennobled you."[72]

Brooks did not always ennoble her subjects. Inherited wealth freed her from the need to sell her paintings; she did not care whether she pleased her sitters or not, and her wit, when unleashed, could be devastating. A striking example is her 1914–1915 portrait of Elsie de Wolfe, an interior designer who she felt had copied her monochromatic color schemes. Brooks painted de Wolfe porcelain-pale, in an off-white dress and a bonnet resembling a shower cap; a white ceramic goat placed on a table at her elbow seems to mimic her simpering expression.[73]

One of Brooks's more analyzed paintings, a 1924 portrait of Una, Lady Troubridge, has been seen as everything from an image of female self-empowerment to a caricature.[74] Art critic Michael Duncan sees the painting as making fun of Troubridge's "dandified appearance", while for Meryle Secrest it is "a tour de force of ironic commentary".[75] Laura Doan, pointing out newspaper and magazine articles from 1924 in which high collars, tailored satin jackets, and watch fobs are described as the latest in women's wear, describes Troubridge as having a "keen fashion sense and an eye for sartorial detail".[76] But, these British fashions may not have been favored in Paris; Natalie Barney and others in her circle considered Troubridge's outfits ridiculous.[77] Brooks expressed her own view in a letter to Barney: "Una is funny to paint. Her get-up is remarkable. She will live perhaps and cause future generations to smile."[78]

In 2016, Smithsonian magazine featured an exhibition of the art of Romaine Brooks, declaring "The world is finally ready to understand Romaine Brooks."[79]

Gallery

Dame en Deuil, oil on canvas, c. 1910 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Dame en Deuil, oil on canvas, c. 1910 (Smithsonian American Art Museum) Ida Rubinstein, oil on canvas, 1917 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Ida Rubinstein, oil on canvas, 1917 (Smithsonian American Art Museum) La Baronne Emile D’Erlanger , oil on canvas, c. 1924 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

La Baronne Emile D’Erlanger , oil on canvas, c. 1924 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

References

Notes

- ↑ Latimer, Women Together, 51.

- ↑ Meagher M. "Romaine Brooks: A Life". JSTOR 26430731. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Langer, Cassandra (2015). Romaine Brooks: A Life. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin. p. 68. ISBN 978-0299298609.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Group: an officer of high rank and his wife. B.C. 1300. (B.M.)". Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema Collection Online. doi:10.1163/37701_atco_pf_8807. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ↑ Chadwick, Whitney (2000). Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 128. ISBN 978-0-520-22567-1.

amazons in the drawing room.

- ↑ Secrest, 17–42.

- ↑ Rodriguez, 223.

- 1 2 Hawthorne, Melanie (January 2, 2016). "When You Cannot Run, You Cannot Hide: Romaine Brooks Draws (On) the Past". Romance Studies. 34 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1080/02639904.2015.1123548. ISSN 0263-9904. S2CID 163362882.

- ↑ Secrest, 108–109.

- ↑ Secrest, 123–145, 173.

- ↑ Secrest, 179–181.

- ↑ Diana Souhami (2004) Wild Girls

- ↑ Morgan, Ted (1980). Somerset Maugham. Royal National Institute for the Blind. OCLC 1012118099.

- ↑ Secrest, 186–189.

- ↑ Chadwick, 18–19.

- ↑ Lucchesi, Apparition, 75–76.

- ↑ Secrest, 197, 204–206.

- ↑ Latimer, "Sapphic Modernity", 38.

- ↑ See Romaine Brooks, On The Hills of Florence, SIA available online.

- ↑ Secrest, 193.

- ↑ Lucchesi, "Apparition", 80 and Secrest, 243–244.

- ↑ Secrest, 243.

- ↑ From Brooks's unpublished memoir No Pleasant Memories; quoted in Lucchesi, "Apparition", 85.

- ↑ Secrest, 248.

- 1 2 Chadwick, 27–28.

- 1 2 Chadwick, 22–23.

- ↑ Chadwick, 13, discusses D'Annunzio's influence; Langer, 47n5 and 47n9, cautions that: "Brooks's support of Fascism has not been documented" but seems to agree she had some Fascist sympathies; Warren discusses her own reaction to Brooks's politics.

- ↑ Langer, 64–65.

- ↑ Lucchesi, "Apparition", 84–85.

- ↑ Rodriguez, 295–301.

- ↑ Souhami, 137–139, 146, and Secrest, 277.

- ↑ Rodriguez, 227, 295.

- ↑ Langer, 46.

- ↑ Elliott and Wallace, 15 and 27n9.

- ↑ Wickes, 257.

- ↑ Ryersson, Scot D. and Michael Orlando Yaccarino. Infinite Variety: The Life and Legend of the Marchesa Casati, University of Minnesota Press, 2004, pp. 107–112.

- ↑ Doan, 114–117 and passim.

- ↑ Langer, 45 and Elliott, 74.

- ↑ Doan, 117–119.

- ↑ Elliott, 73.

- 1 2 Duncan (2002).

- ↑ Taylor, 13.

- ↑ Elliott and Wallace, 20.

- 1 2 Langer, 45.

- ↑ Chadwick, 33.

- ↑ Cotter (2000).

- ↑ Chadwick, 36.

- ↑ Lucchesi, "Something Hidden", 173–174.

- ↑ Secrest, 286–294.

- ↑ Barnes, 36. Cynic Sal is identified as Brooks in Weiss, 156.

- ↑ "Romaine Goddard Brooks". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ↑ Secrest, 308–310.

- ↑ Chastain, 13–14.

- ↑ Secrest, v.

- ↑ Souhami, 169.

- ↑ Souhami, 178.

- ↑ Chadwick, 37.

- ↑ Souhami, 194.

- ↑ Souhami, 183–184.

- ↑ Secrest, 358.

- ↑ Secrest, 376–377.

- ↑ Souhami, 197.

- ↑ "Brooks, Romaine". Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Secrest, 311.

- ↑ Secrest, 135–136.

- ↑ Secrest, 186.

- ↑ Chadwick, 32.

- ↑ Secrest, 311–312.

- ↑ Chadwick, 8, Langer 204–206. For an extended comparison of Brooks's portraits with a 1990s series of photographs by the transsexual artist Loren Cameron, see Melanie Taylor's "Peter (A Young English Girl): Visualizing Transgender Masculinities."

- ↑ Chadwick, 27, 32.

- ↑ O'Sullivan (2000).

- ↑ Natalie Barney, Aventures de l'Esprit, quoted in Jay, 30.

- ↑ Langer, 46 and Secrest, 199 and 325–326.

- ↑ Cassandra Langer calls it an image of female self-empowerment in "Transgressing Le droit du seigneur: The Lesbian Feminist Defining Herself in Art History," New Feminist Criticism: Art-Identity-Action, Joanna Frueh, Cassandra Langer, and Arlene Raven, eds. New York: HarperCollins, 1994. 320. Quoted in Chadwick, 35. Secrest, 124, describes it as a caricature.

- ↑ Secrest, 199.

- ↑ Doan, 116–117.

- ↑ Rodriguez, 272.

- ↑ Secrest, 292.

- ↑ "History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places | Smithsonian". www.smithsonianmag.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

Sources

- Barnes, Djuna (1992). Ladies Almanack. Introduction by Susan Sniader Lanser. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1180-4.

- Chadwick, Whitney (2000). Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks. Essay by Joe Lucchesi. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22567-1.

- Chastain, Catherine McNickle (Fall 2001 – Winter 2002). "Romaine Brooks: A New Look at Her Drawings". Woman's Art Journal. 17 (2): 9–14. doi:10.2307/1358461. JSTOR 1358461.

- Cotter, Holland (August 25, 2000). "ART REVIEW; Politics Runs Through More Than Campaigns". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- Doan, Laura (2001). Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11007-5.

- Duncan, Michael (March 2002). "Our Miss Brooks". Art in America. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007.

- Elliott, Bridget. "Performing the Picture or Painting the Other: Romaine Brooks, Gluck and the Question of Decadence in 1923." Deepwell, Katy (1998). Women Artists and Modernism. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5082-4.

- Elliott, Bridget; Wallace, Jo-Ann (Spring 1992). "Fleurs du Mal or Second-Hand Roses?: Natalie Barney, Romaine Brooks, and the 'Originality of the Avant-Garde'". Feminist Review (40): 6–30. doi:10.2307/1395274. JSTOR 1395274.

- James, Jamie (2019). Pagan Light: Dreams of Freedom and Beauty in Capri. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374142766.

- Jay, Karla (1988). The Amazon and the Page. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20476-9.

- Langer, Cassandra; Chadwick, Whitney; Lucchesi, Joe (Autumn 2001 – Winter 2002). "Review of Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks by Whitney Chadwick; Joe Lucchesi". Woman's Art Journal. 22 (2): 44–47. doi:10.2307/1358903. JSTOR 1358903.

- Langer, Cassandra (2016). Romaine Brooks: A Life. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Latimer, Tirza True (2005). Women Together / Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3595-1.

- Latimer, Tirza True (2006). "Romaine Brooks and the Future of Sapphic Modernity." Doan, Laura; Jane Garrity (2006). Sapphic Modernities: Sexuality, Women and English Culture. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 35–54. ISBN 978-1-4039-6498-4.

- Lockard, Ray Anne (2002). "Brooks, Romaine". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved October 13, 2006.

- Lucchesi, Joe. (2000). "'An Apparition in a Black Flowing Cloak': Romaine Brooks's Portraits of Ida Rubinstein." Chadwick, Amazons in the Drawing Room, 73–87.

- Lucchesi, Joe. (2003). "'Something Hidden, Secret, and Eternal': Romaine Brooks, Radclyffe Hall, and the Lesbian Image in 'The Forge'". Chadwick, Whitney; Tirza True Latimer (2003). The Modern Woman Revisited. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 169–179. ISBN 978-0-8135-3292-9.

- O'Sullivan, Michael (August 4, 2000). "Romaine Brooks: Sex and the Sitters". The Washington Post. pp. N51. Retrieved October 13, 2006.

- Rodriguez, Suzanne (2002). Wild Heart: A Life: Natalie Clifford Barney and the Decadence of Literary Paris. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-093780-5.

- Ryersson, Scot D.; Michael Orlando Yaccarino (September 2004). Infinite Variety: The Life and Legend of the Marchesa Casati (Definitive ed.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4520-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Secrest, Meryle (1974). Between Me and Life: A Biography of Romaine Brooks. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-03469-2.

- Souhami, Diana (2005). Wild Girls: Paris, Sappho, and Art: The Lives and Loves of Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-34324-8.

- Taylor, Melanie (May 2004). "Peter (A Young English Girl): Visualizing Transgender Masculinities". Camera Obscura. 19 (56): 1–45. doi:10.1215/02705346-19-2_56-1. S2CID 144579965.

- Warren, Nancy (October 20, 2000). "Romaine Brooks: Amazons and Artists". SF Gate. Retrieved November 5, 2006.

- Weiss, Andrea (1995). Paris Was a Woman: Portraits from the Left Bank. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-251313-7.

External links

- Romaine Brooks at WikiCommons

- Romaine Brooks at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Romaine Brooks gallery

- Romaine Brooks biography, artwork and memoirs — Trivium Art History

- A finding aid to Romaine Brooks papers, 1910–1973, at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution