In bipack color photography for motion pictures, two strips of black-and-white 35 mm film, running through the camera emulsion to emulsion, are used to record two regions of the color spectrum, for the purpose of ultimately printing the images, in complementary colors, superimposed on one strip of film. The result is a multicolored projection print that reproduces a useful but limited range of color by the subtractive color method. Bipack processes became commercially practical in the early 1910s when Kodak introduced duplitized film print stock, which facilitated making two-color prints.[1]

Bipack photography was, from about 1935 to 1950, the most economical means of 35 mm natural color cinematography available, used when color was wanted but the budget could not bear the much higher cost of three-strip Technicolor or the less well-known alternative three-color processes sometimes available outside the US. After 1950, when economical "monopack" color negative and print stocks such as Eastmancolor and Ansco Color were introduced, the use of bipack photography and printing rapidly declined. By 1955 all two-color motion picture processes were commercially extinct in the US.

Bipack and three-element tripack sandwiches of plates and films were used in some early color processes for still photography, the field in which the concept originated.

How it works

Bipack color refers to the type of camera load that is used for the effect. Bipack photography refers to two strips running through the camera at once, for the purpose of recording two different spectra of light, generally.

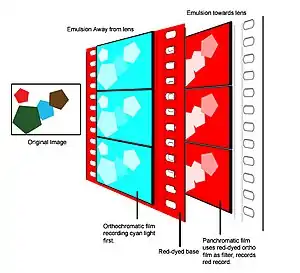

Color photography begins with any standard camera. Special magazines or adapters must be provided to accommodate two separate rolls of film. Two films are loaded, passing through the photographing aperture with the emulsions towards each other. The front film is orthochromatic, to record the blue-green portion of the picture. On the surface of its emulsion is a red-dye layer equivalent to a Wratten 23A filter. The rear film is panchromatic, and being photographed through the red coating of the front film, records only the red-orange components of the picture. No filtering is necessary either for exterior or interior photography, as all necessary color corrections are made by adjusting the development of the two negatives during printing.

Since the image must be focused on the plane of contact of the two negatives used, lenses and focusing screens used in bipack photography would be readjusted to throw the plane of focus .006" behind that of the standard black-and-white plane.

Care would be taken to avoid photographing objects of purple, lavender or pink coloring, as bipack color generally cannot reproduce these colors in printing.

After processing the two negatives, the red and cyan records were printed separately on a single strip of Eastman or DuPont duplitized stock. Since the red negative was reversed in camera (that is, its emulsion away from the lens), there was no optical printing required to focus the image, and thus contact printing on both emulsions took place. Both sides were toned by floating each side in a tank with the complementary colors (cyan for the side exposed with the red negative and vice versa) using toning chemicals or through dye mordanting.

Bipack color processors

Over the years, a great number of bipack color processors existed, largely due to the lack of holding patents on processing in this method. These systems included:

- Kodachrome (1915), Eastman-Kodak's first color system

- Prizma (1918–1928)

- Brewster Color (1913-193?)

- Magnacolor (1928-194?), by Consolidated Film, a direct offshoot of Prizma

- Colorcraft (1929)

- Harriscolor (1929)

- Multicolor (1929–1932), a company financed by Howard Hughes

- Photocolor (1930)

- Sennettcolor (1930)

- DuPack Process (1932)

- Cinecolor (1932–1954), the most popular bi-pack processor, an offshoot of Multicolor

- Polychrome

- Kesdacolor

- Douglass Color (second process)

- Dascolor

- Cinefotocolor

- Colorfilm process

In addition, Consolidated Film also owned the Trucolor color system, which was shot as bipack color, but processed with special duplitized stock produced by the DuPont company that carried a dye-coupler.

For the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, the Technicolor Corporation devised a bipack color filming process – dubbed "Technichrome" – whereby hundreds of hours of film documented the Olympics in color, without having to ship expensive and heavy Technicolor cameras to London.[2]

References

- ↑ "Bi-pack". Timeline of Historical Film Colors.

- ↑ Widescreen Museum entry