Braids (also referred to as plaits) are a complex hairstyle formed by interlacing three or more strands of hair.[1] Braiding has been used to style and ornament human and animal hair for thousands of years[2] in various cultures around the world.

The simplest and most common version is a flat, solid, three-stranded structure. More complex patterns can be constructed from an arbitrary number of strands to create a wider range of structures (such as a fishtail braid, a five-stranded braid, rope braid, a French braid and a waterfall braid). The structure is usually long and narrow with each component strand functionally equivalent in zigzagging forward through the overlapping mass of the others. Structurally, hair braiding can be compared with the process of weaving, which usually involves two separate perpendicular groups of strands (warp and weft).

History

.JPG.webp)

The oldest known reproduction of hair braiding may go back about 30,000 years: the Venus of Willendorf in Austria, now known in academia as the Woman of Willendorf, is a female figurine estimated to have been made between about 28,000 and 25,000 BCE.[3] It has been disputed whether or not she wears braided hair or some sort of a woven basket on her head. The Venus of Brassempouy in France is estimated to be about 25,000 years old and ostensibly shows a braided hairstyle.

Another sample of a different origin was traced back to a burial site called Saqqara located on the Nile River, during the first dynasty of Pharaoh Menes, although the Venus' of Brassempouy and Willendorf predate these examples by some 25,000-30,000 years.

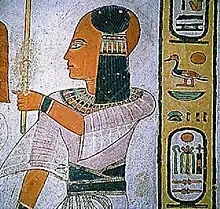

During the Bronze Age and Iron Age many peoples in West Asia, Asia Minor, Caucasus, Southeast Europe, East Mediterranean, Balkans and North Africa such as the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Elamites, Hittites, Arameans, Minoans, Greeks, Persians, Israelites, Canaanites, Phoenicians, Hurrians, Etruscans, Phrygians, Dacians, Arabs, Hyksos, Parthians, Medes, Scythians, Chaldeans, Berbers, Mycenaen Greeks, Luwians ,Armenians, Colchians and Ancient Egyptians were depicted in art with braided or platted hair and beards.[4][5] There has also been found bog bodies in Northern Europe wearing braided hairstyles from the Northern European Iron Age, and later still such braided styles were found among the Celts, Iberians and Vikings in northern, western and southwestern Europe.[6][7]

In some regions, a braid was a means of communication. At a glance, one individual could distinguish a wealth of information about another, whether they were married, mourning, or of age for courtship, simply by observing their hairstyle. Braids were a means of social stratification. Certain hairstyles were distinctive to particular tribes or nations. Other styles informed others of an individual's status in society.

African people such as the Himba people of Namibia have been braiding their hair for centuries. In many African tribes, hairstyles are unique and used to identify each tribe. Braid patterns or hairstyles can be an indication of a person's community, age, marital status, wealth, power, social position, and religion.[8]

.jpg.webp)

On July 3, 2019, California became the first US state to prohibit discrimination over natural hair. Governor Gavin Newsom signed the CROWN Act into law, banning employers and schools from discriminating against hairstyles such as dreadlocks, braids, afros, and twists.[9] Later in 2019, Assembly Bill 07797 became law in New York state; it "prohibits race discrimination based on natural hair or hairstyles."[10]

Braiding is traditionally a social art. Because of the time it takes to braid hair, people have often taken time to socialize while braiding and having their hair braided. It begins with the elders making simple knots and braids for younger children. Older children watch and learn from them, start practicing on younger children, and eventually learn the traditional designs. This carries on a tradition of bonding between elders and the new generation.

There are a number of different types of braided hairstyles, including, commonly, French braids, corn rows, and box braiding.[11] Braided hairstyles may also be used in combination with or as an alternative to simpler bindings, such as ponytails or pigtails. Braiding may also be used to add ornamentation, such as beads or hair extensions, as in crochet braiding.

Braiding is also used to prepare horses' manes and tails for showing such as in polo and polocrosse.[12]

Braiding in particular cultures

Indian braids

In India, braiding is common in both rural and urban areas. Girls are seen in twin braids especially in schools, though now it is becoming less common. Young girls usually have one long braid. Married women have a bun or a braided bun.

%252C_Tamil_Nadu%252C_India%252C_late_1800s_to_early_1900s%252C_gold%252C_silver%252C_cotton%252C_rubies_-_Freer_Gallery_of_Art_-_DSC04483.jpg.webp)

African and African American braids

Braids have been part of black culture going back generations. There are pictures going as far back as the year 1884 showing a Senegalese woman with braided hair in a similar fashion to how they are worn today.[13]

Braids are normally done tighter in black culture than in others, such as in cornrows or box braids. While this leads to the style staying in place for longer, it can also lead to initial discomfort. This is commonly accepted and managed through pain easing techniques. Some include pain killers, letting the braids hang low, and using leave-in-conditioner.[14] Alternative braiding techniques like knotless braids, which incorporate more of a person's natural hair and place less tension on the scalp, can cause less discomfort.[15]

Braids are not usually worn year-round in black culture; they are instead alternated with other popular hairstyles such as hair twists, protective hairstyles and more. Curly Mohawk, Half Updo and Side-Swept Cornrows braids are some of the popular and preferred styles in black culture.[16] As long as braids are done with a person's own hair, it can be considered as part of the natural hair movement.

Asia and America

In India, many Hindu ascetics wear dreadlocks, known as Jatas.[17] Young girls and women in India often wear long braided hair at the back of their neck.[18] In the Upanishads, braided hair is mentioned as one of the primary charms of female seduction.[19] A significant tradition of braiding existed in Mongolia, where it was traditionally believed that the human soul resided in the hair. Hair was only unbraided when death was imminent.[20][21] In Japan, the Samurai sported a high-bound ponytail (Chonmage), a hairstyle that is still common among Sumo wrestlers today. Japanese women wore various types of braids (三つ編み) until the late 20th century because school regulations prohibited other hairstyles, leaving braids and the bob hairstyle as the main options for girls.[22] In China, girls traditionally had straight-cut bangs and also wore braids (辮子). The Mandu men have historically braided their hair. After conquering Beijing in 1644 and establishing the Qing Dynasty, they forced the men of the subjugated Han Chinese to adopt this hairstyle as an expression of loyalty, which involved shaving the forehead and sides and leaving a long queue at the back (剃髮易服). The Han Chinese considered this a humiliation as they had never traditionally cut their hair due to Confucian customs. The last emperor, Puyi, cut off his queue in 1912, marking the end of this male hairstyle in China, the same year when China became a republic.[23][24]

Braided hairstyles were widespread among many North American indigenous peoples, with traditions varying greatly from tribe to tribe. For example, among the Quapaw, young girls adorned themselves with spiral braids, while married women wore their hair loose.[25] Among the Lenape, women wore their hair very long and often braided it.[26][27] Among the Blackfoot, men wore braids, often on both sides behind the ear.[28] The men of the Kiowa tribe often wrapped pieces of fur around their braids. Among the Lakota, both men and women had their hair braided into 2, with men’s being typically longer than women’s. Some had their hair wrapped in furs, typically bison. During times of war, warriors would often have their hair unbraided as a sign of fearlessness. Among the Maya, women had intricate hairstyles with two braids, while men had a single large braid that encircled the head.[29]

In Jamaica, the Rastafari movement emerged in the 1930s, a Christian faith practiced by descendants of African slaves who often wear dreadlocks and untrimmed beards, in adherence to the Old Testament prohibition on cutting hair.

Braids in Eroticism and Psychoanalysis

Some fetishists find braids to be a strong erotic stimulus. Most commonly, the tightly woven French braid, known as the French braid, is mentioned in this context.

In the older psychiatric literature, there are occasional references to fetishists who, in order to possess the desired object, would cut off female braids. For example, Swiss psychiatrist Auguste Forel described the case of a braid-cutter in Berlin in 1906, who was found in possession of 31 braids.[30] Richard von Krafft-Ebing had already explored a deeper understanding of hair fetishism in the late 19th century.[31]

In psychoanalytic literary interpretation, authors have continued to explore braid-cutters to this day. Notably, an episode in Ernest Hemingway's novel For Whom the Bell Tolls has aroused considerable interest.[32][33] Sigmund Freud had interpreted hair-cutting as a symbolic castration in Totem and Taboo (1913).[34] Some authors later followed him in seeing the braid as a phallic symbol.[35][36][37] Others interpreted braids as a symbol of virginity and the unbraiding or cutting of the braid as a symbol of defloration [38]

See also

References

- ↑ Kyosev, Yordan (2014). Braiding technology for textiles. Woodheshit Publishing. ISBN 9780857091352.

- ↑ "History of Cornrow Braiding". rpi.edu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "Nude woman (Venus of Willendorf)". khanacademy.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "The history of hair, hair styles through the ages". Archived from the original on 2007-04-26. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- ↑ "BRAIDS HAIRSTYLES 2018". Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Gill-Robinson, Heather (2005). The Iron Age Bog Bodies of the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schloss Gottorf. p. 63.

- ↑ Van der Sanden, Through Nature to Eternity, p. 145; diagram of how it was tied, Ill. 202, p. 146

- ↑ "African Tribes and the Cultural Significance of Braiding Hair". Bright Hub Education. 9 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ "California bans racial discrimination based on hair in schools and workplaces". JURIST. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ↑ "New York bans discrimination against natural hair". The Hill. 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- ↑ "Braid Hairstyles Guide - DIY". Iknowhair.com. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- ↑ Braiding and Plaiting Your Horse Archived 2010-02-01 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-2-20

- ↑ BB, Miss (2016-06-22). "Do cornrows come from Africa?". BLACK AND BEAUTIFUL. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ "How To Relieve Pain From Tight Braids And Soothe". That Sister. 2019-01-06. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ Garcia, Sandra E. (2022-08-09). "The Rise of Knotless Braids". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ↑ "Best Braid Hairstyles For Black Women". 15 November 2019.

- ↑ Rampuri (2010). Autobiography of a Sadhu. A Journey Into Mystic India. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books. pp. 25, 73. ISBN 978-1-59477-330-3. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ S. Gajrani (2004). History, Religion & Culture of India. Delhi: Isha Books. p. 88. ISBN 81-8205-059-6. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Yajnavalkya Upanishad". Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Carole Pegg (2001). Mongolian Music, Dance, & Oral Narrative. Performing Diverse Identities (1st ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-295-98112-1. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Paula L. W. Sabloff, ed. (2001). Modern Mongolia. Reclaiming Genghis Khan (1st ed.). University of Pennsylvania. p. 73. ISBN 0-924171-90-1. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Victoria Sherrow (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair. A Cultural History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-313-33145-6. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus & Han. Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. p. 60. ISBN 0-295-97938-0. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Millicent Marcus (2002). After Fellini. National Cinema in the Postmodern Age. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 305. ISBN 0-8018-6847-5. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Indians in Arkansas: The Quapaw" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF; 696 kB) on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Clothing and Decoration". 2014-07-15. Archived from the original on 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "The Lenape Tribe". Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Blackfeet Tribe, How they Lived". Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Sylvanus Griswold Morley (1915). An Introduction to the Study of the Maya Hieroglyphs. Courier Dover. p. 7.

- ↑ Auguste Forel (1966). Die sexuelle Frage. Eine naturwissenschaftliche, psychologische und hygienische Studie nebst Lösungsversuchen wichtiger sozialer Aufgaben der Zukunft (19th ed.). München. p. 281.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1892). Psychopathia Sexualis. Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der conträren Sexualempfindung. Stuttgart. pp. 166–169. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Carl Pl Eby (1999). Hemingway’s Fetishism. Psychoanalysis and the Mirror of Manhood. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 79 ff. ISBN 0-7914-4003-6. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "History and Origin of Dreads". Knotty Boy. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ↑ "Totem und Tabu, Absatz 204". Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Timothy Murray (1993). Like a Film. Ideological Fantasy on Screen, Camera and Canvas. London: Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 0-415-07734-6. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Ralf Junkerjürgen (2009). Haarfarben. Eine Kulturgeschichte in Europa seit der Antike. Köln/ Weimar/ Wien: Böhlau. pp. 243 f. ISBN 978-3-412-20392-4. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Jay Geller (2005). Christopher E. Forth, Ivan Crozier (ed.). Hairy Heine, or the Braiding of Gender and Ethnik Difference. Lexington. pp. 105–122. ISBN 0-7391-0933-2.

- ↑ Max Marcuse, ed. (2001). Handwörterbuch der Sexualwissenschaft. Enzyklopädie der natur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Sexualkunde des Menschen. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 261 f. ISBN 3-11-017038-8.