| Battle of Brandy Station | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Cavalry Charge Near Brandy Station by Edwin Forbes | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alfred Pleasonton | J. E. B. Stuart | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac | Cavalry Division, Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11,000 | 9,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

The Battle of Brandy Station, also called the Battle of Fleetwood Hill, was the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the American Civil War, as well as the largest ever to take place on American soil.[4] It was fought on June 9, 1863, around Brandy Station, Virginia, at the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign by the Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton against Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart's Confederate cavalry.

Union commander Pleasonton launched a surprise dawn attack on Stuart's cavalry at Brandy Station. After an all-day fight in which fortunes changed repeatedly, the Federals retired without discovering Gen. Robert E. Lee's infantry camped near Culpeper. This battle marked the end of the Confederate cavalry's dominance in the East. From this point in the war, the Federal cavalry gained strength and confidence.

Background

The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia streamed into Culpeper County, Virginia, after its victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863. Under the leadership of Gen. Robert E. Lee, the troops massed around Culpeper preparing to carry the war north into Pennsylvania. The Confederate Army was suffering from hunger and their equipment was poor. Lee was determined to strike north to capture horses, equipment, and food for his men. His army could also threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and encourage the growing peace movement in the North. By June 5, two infantry corps under Lt. Gens. James Longstreet and Richard S. Ewell were camped in and around Culpeper. Six miles northeast of Culpeper, holding the line of the Rappahannock River, Stuart bivouacked his cavalry troopers, screening the Confederate Army against surprise by the enemy.[5]

Most of the Southern cavalry was camped near Brandy Station. Stuart, befitting his reputation as a "dashing cavalier" or beau sabreur,[6] requested a full field review of his troops by Lee. This grand review on June 5 included nearly 9,000 mounted troopers and four batteries of horse artillery, charging in simulated battle at Inlet Station, about two miles (3 km) southwest of Brandy Station.[7] (The review field currently remains much as it was in 1863, except that a Virginia police station occupies part of it.)

Lee was not able to attend the review, however, so it was repeated in his presence on June 8, although the repeated performance was limited to a simple parade without battle simulations.[8] Despite the lower level of activity, some of the cavalrymen and the newspaper reporters at the scene complained that all Stuart was doing was feeding his ego and exhausting the horses. Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock River the next day and raid Union forward positions, screening the Confederate Army from observation or interference as it moved north. Anticipating this imminent offensive action, Stuart ordered his tired troopers back into bivouac around Brandy Station.[9]

Opposing forces and Pleasonton's plan

Around Brandy Station, Stuart's force of about 9,500 men consisted of five cavalry brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens. Wade Hampton, W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee, Beverly H. Robertson, William E. "Grumble" Jones, and Colonel Thomas T. Munford (commanding Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee's brigade while Lee was stricken with a bout of rheumatism), plus the six-battery Stuart Horse Artillery, commanded by Major Robert F. Beckham.[10]

Unknown to the Confederates, 11,000 Union men had massed on the other side of the Rappahannock River. Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, commanding the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac, had organized his combined-armed forces into two "wings," under Brig. Gens. John Buford and David McMurtrie Gregg, augmented by infantry brigades from the V Corps.[11] Buford's wing, accompanied by Pleasonton, consisted of his own 1st Cavalry Division, a reserve brigade led by Major Charles J. Whiting, and an infantry brigade of 3,000 men under Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames. Gregg's wing was the 2nd Cavalry Division, led by Col. Alfred N. Duffié, the 3rd Cavalry Division, led by Gregg, and an infantry brigade under Brig. Gen. David A. Russell.[10]

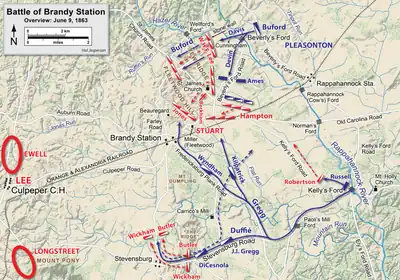

The commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, interpreted the enemy's cavalry presence around Culpeper to be indicative of preparations for a raid of his army's supply lines. In reaction to this, he ordered Pleasonton's force on a "spoiling raid",[9] to "disperse and destroy" the Confederates.[12] Pleasonton's attack plan called for a two-pronged thrust at the enemy. Buford's wing would cross the river at Beverly's Ford, two miles (3 km) northeast of Brandy Station; at the same time, Gregg's would cross at Kelly's Ford, six miles (10 km) downstream to the southeast. Pleasonton anticipated that the Southern cavalry would be caught in a double envelopment, surprised, outnumbered, and beaten. He was, however, unaware of the precise disposition of the enemy and he incorrectly assumed that his force was substantially larger than the Confederates he faced.[13]

Battle

About 4:30 a.m. on June 9, Buford's column crossed the Rappahannock River in a dense fog, pushing aside the Confederate pickets at Beverly's Ford. Pleasonton's force had achieved its first major surprise of the day. Jones's brigade, awakened by the sound of nearby gunfire, rode to the scene partially dressed and often riding bareback. They struck Buford's leading brigade, commanded by Col. Benjamin F. Davis, near a bend in the Beverly's Ford Road and temporarily checked its progress, and Davis was killed in the ensuing fighting. Davis's brigade had been stopped just short of where Stuart's Horse Artillery was camped and was vulnerable to capture. Cannoneers swung one or two guns into position and fired down the road at Buford's men, enabling the other pieces to escape and establish the foundation for the subsequent Confederate line.

The artillery unlimbered on two knolls that were on either side of the Beverly's Ford Road. Most of Jones's command rallied to the left of this Confederate artillery line, while Hampton's brigade formed to the right. The 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (led by Major Robert Morris, Jr.) unsuccessfully charged the guns at St. James Church, suffering the greatest casualties of any regiment in the battle. Several Confederates later described the 6th's charge as the most "brilliant and glorious" cavalry charge of the war. (In many Civil War battles, cavalrymen typically dismounted once they reached an engagement and fought essentially as infantry. But in this battle, the surprise and chaos led to a mostly mounted fight.)[14]

Buford tried to turn the Confederate left and dislodge the artillery that was blocking the direct route to Brandy Station. However, Rooney Lee's brigade stood in his way, with some troops on Yew Ridge and some dismounted troopers positioned along a stone wall in front. After sustaining heavy losses, the Federals displaced the Confederates from the stone wall. Then, to the amazement of Buford's men, the Confederates began pulling back. They were reacting to the arrival of Gregg's Union cavalry division of about 2,800 men, which was the second major surprise of the day. Gregg had intended to cross at Kelly's Ford at dawn, in concert with Buford's crossing at Beverly's, but assembling the men from dispersed locations and Duffié's division getting lost on the way cost them two hours. They had intended to proceed on roads leading directly into Brandy Station, but discovered the way blocked by Robertson's brigade. Gregg found a more circuitous route that was completely unguarded and, following these roads, his lead brigade under Col. Percy Wyndham arrived in Brandy Station about 11 a.m.

Between Gregg and the St. James battle was a prominent ridge called Fleetwood Hill, which had been Stuart's headquarters the previous night. Stuart and most of his staff had departed for the front by this time and the only force on Fleetwood when Gregg arrived was a howitzer, left in the rear because of inadequate ammunition. Major Henry B. McClellan, Stuart's adjutant, called Lt. John W. Carter and his gun crew (of Captain Robert P. Chew's battery) to ascend to the crest of the hill and go into action with the few shells available, as he sent an urgent request to Stuart for reinforcements. Carter's few shots delayed the Union advance as they sent out skirmishers and returned cannon fire. When Wyndham's men charged up the western slope of Fleetwood and neared the crest, the lead elements of Jones's brigade, which had just withdrawn from St. James Church, rode over the crown.[15][16][17]

Gregg's next brigade, led by Col. Judson Kilpatrick, swung around east of Brandy Station and attacked up the southern end and the eastern slope of Fleetwood Hill, only to discover that their appearance coincided with the arrival of Hampton's brigade. A series of confusing charges and countercharges swept back and forth across the hill. The Confederates cleared the hill for the final time, capturing three guns and inflicting 30 casualties among the 36 men of the 6th New York Light Artillery, which had attempted to give close-range support to the Federal cavalry. Col. Duffié's small 1,200-man division was delayed by two Confederate regiments in the vicinity of Stevensburg and arrived on the field too late to affect the action.[18]

While Jones and Hampton withdrew from their initial positions to fight at Fleetwood Hill, Rooney Lee continued to confront Buford, falling back to the northern end of the hill. Reinforced by Fitzhugh Lee's brigade, Rooney Lee launched a counterattack against Buford at the same time as Pleasonton had called for a general withdrawal near sunset, and the ten-hour battle was over.[19]

Aftermath

[Brandy Station] made the Federal cavalry. Up to that time confessedly inferior to the Southern horsemen, they gained on this day that confidence in themselves and in their commanders which enable them to contest so fiercely the subsequent battle-fields ...

Major Henry B. McClellan, Stuart's adjutant[20]

Union casualties were 907 (69 killed, 352 wounded, and 486 missing, primarily captured); Confederate losses totaled 523.[2] Some 20,500 men were engaged in this, the largest predominantly cavalry battle to take place during the war.[21] Among the casualties was Robert E. Lee's son, Rooney, who was seriously wounded in the thigh. He was sent to Hickory Hill, an estate near Hanover Court House, where he was captured on June 26.

Stuart argued that the battle was a Confederate victory since he held the field at the end of the day and had repelled Pleasonton's attack. The Southern press was generally negative about the outcome. The Richmond Enquirer wrote that "Gen. Stuart has suffered no little in public estimation by the late enterprises of the enemy." The Richmond Examiner described Stuart's command as "puffed up cavalry," that suffered the "consequences of negligence and bad management."[22]

Subordinate officers criticized Pleasonton for not aggressively defeating Stuart at Brandy Station. Maj. Gen. Hooker had ordered Pleasonton to "disperse and destroy" the Confederate cavalry near Culpeper, but Pleasonton claimed that he had only been ordered to make a "reconnaissance in force toward Culpeper," thus rationalizing his actions.[23]

For the first time in the Civil War, Union cavalry matched the Confederate horsemen in skill and determination.[24] Stuart falling victim to two surprise attacks, which cavalry was supposed to prevent, foreshadowed other embarrassments ahead for him in the Gettysburg campaign.[25]

Battlefield preservation

The Brandy Station Foundation (BSF) was formed to protect the Brandy Station Battlefield from development. According to Clark B. Hall, "a small group of citizens came together over coffee in a little home situated just south of the Rappahannock River in eastern Culpeper County, Virginia".[26] Over time the organization grew to over 400 members and has been the cornerstone of efforts to save the battlefield from attempts to turn it into an office park, and a racetrack, as well as preserving the historic building known as Graffiti House. In 1990, the National Park Service completed mapping of historic resources at Brandy Station and recommended preservation of 1,262 acres (5.1 km²) at four separate engagement areas.

The American Battlefield Trust, formerly known as The Civil War Trust, has been the major preservation organization involved at Brandy Station. The Trust, supplemented by the BSF and other partners, has acquired and preserved 2,159 acres (8.74 km2) of the battlefield in more than 15 separate acquisitions from 1997 through November 2021.[27][3] In 2003, this led to the opening of Brandy Station Battlefield Park, which interprets the history of the site. This work has prevented a number of commercial enterprises from infringing on the battleground, including a proposed Formula One racetrack in the late 1990s.[28] In 2013, the Trust achieved a major preservation success by purchasing a 61-acre tract at Fleetwood Hill, site of a number of significant cavalry charges during the battle.[29] In 2022, Virginia agreed to accept 1700 acres from the Trust and purchase up to 800 additional acres to form the Culpeper Battlefields State Park.[30] The Park is scheduled to open 1 July 2024. [31]

Nancy C. James, former rector of Christ Church, Brandy Station (the diocese rebuilding St. James Episcopal Church nearby and renaming it) and nearby Emmanuel Church, Rapidan, wrote a book describing some of the parish and civic unrest during the 1990-era development controversy, which included reburying at least one previously unidentified Civil War soldier whose original coffin had been made from pews of the destroyed church.[32]

Notes

- ↑ "American Battlefield Protection Program (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-08-13. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- 1 2 3 Eicher, p. 493.

- 1 2 "Battle of Brandy Station Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. January 14, 2009. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ↑ Brandy Station Foundation (Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine). Of the 20,500 men engaged, approximately 3,000 were Union infantrymen. The Battle of Trevilian Station in 1864 was the largest all-cavalry battle of the war. According to the Civil War Trust Archived 2013-05-23 at the Wayback Machine Brandy Station was the largest battle of its kind on American soil.

- ↑ Salmon, pp. 193–94; Loosbrock, p. 272.

- ↑ Longacre, p. 23.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 40–41; Sears, pp. 62–64; NPS website Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 40–41; Sears, pp. 62–64.

- 1 2 Salmon, p. 193.

- 1 2 Salmon, pp. 198–99; Kennedy, p. 202.

- ↑ Longacre, p. 62.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 204. NPS website Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ NPS Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine; Loosbrock, p. 272; Kennedy, p. 204; Salmon, pp. 194, 198; Eicher, p. 492.

- ↑ "Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park - Battle of Brandy Station (U.S. National Park Service)". January 19, 2007. Archived from the original on January 19, 2007.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Salmon, pp. 199–201

- ↑ NPS Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine; Kennedy, p. 204; Salmon, p. 202.

- ↑ NPS Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine; Salmon, p. 202; Eicher, p. 492.

- ↑ Sears, p. 74.

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 202–05. Of the 20,500, approximately 3,000 were Union infantrymen. The Battle of Trevilian Station in 1864 was the largest all-cavalry battle of the war.

- ↑ Sears, p. 73; Salmon, p. 202.

- ↑ Custer, p. 7.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 64–65; Sears, p. 74; Clark, p. 22; Loosbrock, p. 274; Wittenberg and Petruzzi, p. xviii.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 203; Loosbrock, p. 274.

- ↑ Clark B. Hall, "Saving Brandy Station" Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, Civil War News, accessed January 1, 2014.

- ↑ Brandy Station Fleetwood Hill Archived 2019-08-12 at the Wayback Machine American Battlefield Trust Accessed May 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Preservation Groups Announce Grand Opening of Brandy Station Battlefield Park". American Battlefield Trust. April 24, 2017. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ↑ "Civil War Trust Successfully Completes Campaign to Save Fleetwood Hill at Brandy Station Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. August 19, 2013. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ↑ Schemmer, Clint (2022-06-03). "Culpeper Battlefields State Park approved by Virginia General Assembly". Culpeper Star-Exponent. Archived from the original on 2022-06-29. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ Schemmer, Clint (2022-06-21). "Youngkin approves Culpeper Battlefields State Park". Culpeper Star-Exponent. Archived from the original on 2022-06-29. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ Nancy C. James, Standing in the Whirlwind (Pilgrim Press, Cleveland 2005)

References

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4758-4.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Custer, Andie. "The Knight of Romance." Blue & Gray magazine, Spring 2005.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8032-7941-8.

- Loosbrock, Richard D. "Battle of Brandy Station." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Wittenberg, Eric J., and J. David Petruzzi. Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart's Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006. ISBN 1-932714-20-0.

- National Park Service battle description Archived 2006-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- National Park Service history and tour of the battlefield

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

- Beattie, Dan. Brandy Station, 1863: First Step Towards Gettysburg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84603-304-9.

- Gerleman, David J. Warhorse! Union Cavalry Mounts. North & South Magazine (January 1999).

- McKinney, Joseph W. Brandy Station, Virginia, June 9, 1863: The Largest Cavalry Battle of the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006. ISBN 0-7864-2584-9.

- Starr, Stephen Z. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. 2, The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox 1863–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. The Battle of Brandy Station: North America's Largest Cavalry Battle. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-59629-782-1.

- Wittenberg, Eric J., and Daniel T. Davis. Out Flew the Sabres: The Battle of Brandy Station, June 9, 1863. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2016. ISBN 978-1-61121-256-3.