Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld | |

|---|---|

Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld by David von Krafft. | |

| Born | 6 August 1651 Stralsund, Swedish Pomerania |

| Died | 29 January 1722 (aged 70) Läggesta Inn outside of Mariefred, Södermanland, Sweden |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Cavalry Infantry |

| Years of service | 1673−1722 |

| Rank | Field Marshal (Fältmarskalk) |

| Unit | Närke-Värmland Regiment Queen Dowager of the Realm's Horse Life Regiment Uppland Regiment Svea Life Guards |

| Commands held | German Foot Life Regiment Scanian Cavalry Regiment Life Dragoon Regiment |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) |

Elisabeth Funck (m. 1697) |

Count Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld[lower-alpha 1] (6 August 1651 – 29 January 1722) was a Swedish Field Marshal (fältmarskalk) and Royal Councillor. He was mentor and chief military advisor to King Charles XII of Sweden, and served as deputy commander-in-chief of the Carolean Army, an army he assisted both in its education and development.

Rehnskiöld grew up in Swedish Pomerania and studied at Lund University under philosopher Samuel von Pufendorf. He entered Swedish war service in 1673 and participated with distinction in the Battles of Halmstad, Lund, and Landskrona during the Scanian War, where he was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel and Adjutant-General. After the war, he was commander of several regiments, observer and tutor to Duke Frederick IV during the Nine Years' War, and Governor-General of Scania.

In the Great Northern War he was Charles XII's right-hand man in the operative organization of the Carolean Army and drafted the battle plans for the landing at Humlebæk and for the battles of Narva, Düna and Kliszów. In the Battle of Fraustadt in 1706, with his own independent army, he decisively defeated a Saxon-Russian Army under the command of Field Marshal Schulenburg. For his services, Rehnskiöld was appointed Field Marshal and the title of Count. During Charles XII's campaign against Russia, Rehnskiöld was in command during the Battle of Holowczyn and the siege of Veprik, where he was severely injured. After Charles XII became incapacitated by a bullet wound, Rehnskiöld replaced him as commander-in-chief of the Swedish Army during the Battle of Poltava in 1709, where it suffered a decisive defeat.

After the battle, Rehnskiöld became a prisoner of war in Russia and spent the years in captivity together with Count Carl Piper by running a management office in Moscow to assist the other Swedish prisoners of war. Rehnskiöld was exchanged in 1718 and arrived at the siege of Fredriksten just before Charles XII was shot to death. Rehnskiöld later served as commander in western Sweden and, suffering from an old shrapnel injury, died in 1722.

Childhood and Education (1651–1676)

_2_by_Klugschnacker_in_Wikipedia.jpg.webp)

Rehnskiöld was born on 6 August 1651 in Stralsund in Swedish Pomerania. His parents were the government councillor of Pomerania, Gerdt Antoniison Rehnskiöld (1610−1658), originally Keffenbrinck, and Birgitta Torskeskål (died 1655), niece of Baron Johan Adler Salvius.[2][3] Keffenbrinck's ancestors came from Westphalia, and their seat was the castle of Rehne in the northern part of the Münsterland province. Gerdt Rehnskiöld initially served as a scribe in Kammarkollegium, and later as the authorized representative of the Crown at King Gustavus Adolphus' administrative entourage during the King's military campaign in Germany. Thanks to his efforts in the maintenance of the Swedish troops during the Thirty Years War, he became a naturalized Swedish nobleman in 1639 by Queen Kristina and adopted the name Rehnskiöld after his family seat. He was also awarded the Griebenow, Willershusen, and Hohenwarth estates in Pomerania, as well as Stensättra farm in Södermanland. In 1640, the Rehnskiöld family was introduced in the House of Nobility at number 270.[4][5][3]

Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld was the eighth of the Rehnskiölds' eleven children. After his father's death in 1658, Carl Gustav had two brothers and two sisters. The government councillor Philip Christoff von der Lancken and the regional councillor Joachim Cuhn von Owstien, both close friends to Gerdt Rehnskiöld before his death, received custody over the five siblings. The siblings suffered from financial hardship, partly due to Gerdt's money problems during the latter part of his life, and partly because of inheritance disputes between the five siblings and Gerdt Rehnskiöld's third wife and widow Anna Catharina Gärffelt. The guardians had granted her Birgitta Rehnskiöld's family jewelry and 14,000 riksdaler from the heritage. As a result, the siblings complained about their guardians' way of treating them and wrote several letters of complaint to the Swedish government. Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld's brother-in-law Anders Appelman later came to participate more actively in the upbringing of the five siblings, and gave funds to Carl Gustav's and his brothers' continued education. Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld undertook home education and entered Lund University at the age of 20. Here he studied theology, history, language and philosophy. He participated in lectures with historian and philosopher Samuel von Pufendorf, who took notice of the keen student and offered individual lessons under his tutelage. Pufendorf left a lasting impression. Rehnskiöld re-wrote Pufendorf's work Einleitung zur Historie der vornehmsten Reichen und Staaten in Europa (printed in Frankfurt only in 1682), provided the manuscript with Pufendorf's personal comments, and kept it for the remainder of his life.[6][5]

Rehnskiöld joined the Swedish Army at the age of 22, and in 1673 obtained a commission as Ensign at Captain Reinhold Anrep's company in the Närke-Värmland Regiment. Already in the following year, he was appointed lieutenant at the Queen Dowager of the Realm's Horse Life Regiment. In July 1675, he transferred to the Uppland Regiment, and on 12 February 1676 he became an officer of the prestigious Life Guards.[7]

Scanian War (1676–1679)

During the early stages of the Scanian War, Rehnskiöld served at sea with a company of the Life Guards. He was then commanded ashore on the Scanian theater and, during the night between 31 July and 1 August 1676, he carried out his first military operation at Tostebro. Along with parts of his company he conquered a Danish entrenched position after a short battle. When informed of this, King Charles XI made him Captain of the Life Guards, with whom he participated in the Battle of Halmstad on 17 August 1676.[7][8]

Back in the Horse Life Regiment, this time as ryttmästare, Rehnskiöld participated in the Battle of Lund. After his squadron commander Lindhielm was wounded during the battle, Rehnskiöld replaced him and lead his squadron against the enemy. Charles XI was highly impressed by Rehnskiöld's bravery, promoting him on the battlefield to major and transferring him to be Adjutant-General in the General Staff under Erik Dahlbergh's guidance and supervision.[lower-alpha 2] When the Swedish Army retreated from Rönneberga in May 1677, he alternately commanded the van- and rearguards, participating in numerous skirmishes. His efforts won the praise of Dahlbergh, who called Rehnskiöld "one of the most promising young officers in the army" in the presence of Charles XI. In the Battle of Landskrona, Rehnskiöld, along with his two companies, was surrounded by Danish elite units, and the Life Regiment's casualties were the highest among the Swedish regiments participating in the battle. On 5 November 1677, Rehnskiöld was promoted to lieutenant-colonel at the age of 26. He took effective command of the Queen Dowager of the Realm's Horse Life Regiment since its commander, General Rutger von Ascheberg, was commanded elsewhere. Rehnskiöld became a long-standing friend to von Ascheberg, who was Charles XI's chief military advisor and mentor, and whom Rehnskiöld regarded as his teacher in the art of war.[7][10][11]

In the last two years of the war, Rehnskiöld served on the Norwegian front in Bohuslän and participated in the relief of Bohus Fortress, where his career came close to an abrupt end when he was fired upon by a fortified Norwegian force. At Uddevalla's redoubt, he was the main reason that a Danish relief attempt was repelled.[7][10][11]

Interlude before the Great Northern War (1679–1700)

In 1679, peace was concluded with Denmark and the Carolean army was demobilized. Rehnskiöld's rapid rate of promotion slowed: the rank of colonel and raising his own regiment had to wait. In peacetime, Rehnskiöld was acting Lieutenant-Colonel and Adjutant-General, and learnt much about military logistics which proved to be useful in the future. He remained a dutiful royal servant, being one of the "promising young men" mentioned by Charles XI in a letter to Dahlbergh in 1682. In 1689 he became Colonel of the German Foot Life Regiment, an enlisted garrison regiment accommodated in Landskrona, Halmstad, Karlskrona, Malmö, and Helsingborg. With this position, he was made Commandant of Landskrona Citadel.[12]

.jpg.webp)

During 1690 and 1691 the Dutch Republic negotiated with Sweden for volunteers to fight in the war against France. The Swedish King provided 6,000 men, and Rehnskiöld, with the King's blessing, traveled to the Netherlands in the late summer of 1691. For three months he served as a military observer and military tutor to Prince Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp. Rehnskiöld reported to Charles XI on King William III and the Grand Alliance's joint operations, and the lack of discipline among the Allied forces.[11] Rehnskiöld had to personally intervene in a disciplinary trial between the young Swedish officers Axel Gyllenkrok and Carl Magnus Posse. They volunteered for the French Army and tried to escape to the Allied camp in Flanders, where they were arrested but were released after they protested. Charles XI ordered Rehnskiöld to express his stern dissatisfaction to the young officers; through their undisciplined course of action, they had earned the condemnation of the foreign soldiers and, according to the King, they should have acted in accordance with prevalent soldierly manners.[13][14]

On his return to Sweden in 1693 Rehnskiöld received the colonelcy of the Scanian Cavalry Regiment; he was made major-general of cavalry in 1696. After von Ascheberg's death in April 1693, Rehnskiöld came to finish his work of renewing the old allotment system, becoming Charles XI's chief military steward, and was employed in matters of tactics and education. In Herrevad Abbey and Ljungbyhed he organized extensive training activities for his regiment, and worked hard making it well-equipped and combat effective. Under his tutelage, the Scanian Cavalry Regiment became a model regiment in the Swedish cavalry. When Charles XI died in 1697, he was succeeded by his son Charles XII. The new King granted Rehnskiöld the title of Baron, appointed him Governor-General of Scania and lieutenant-general of cavalry.[15][10][16][11]

Rehnskiöld was instrumental in the development of Carolean combat tactics, based on the "national school" which itself derived from the offensive tactics designed by Gustavus Adolphus, Johan Banér and Charles X Gustav. Charles XI was a strong advocate of the national school, which was designed by Rutger von Ascheberg and Erik Dahlbergh. Their disciples, Rehnskiöld and Quartermaster General Carl Magnus Stuart, educated Charles XII in this kind of warfare, and when Stuart was appointed Governor-General of Courland in 1701, Rehnskiöld became the King's chief military adviser and mentor. Rehnskiöld advocated that the infantry should be organized into battalions of 600 men, one-third pikemen and two-thirds musketeers. They would carry out rapid marches with pikes and drawn swords after giving a close-range volley. The cavalry would be divided into companies of 125 men, which would charge in clustered wedge formations at full speed. This tactic was in stark contrast to the continental pattern, which advocated counter-marching during firing and caracole tactics. The Swedish units would come from the same region and thus be able to create strong bonds between the soldiers and officers. Strict discipline and high morale among the troops would be maintained through the Christian religion, and the allegiance sworn to the King and to their regimental colors and standards.[17]

As Governor-General, Rehnskiöld asserted the Crown's interests in Scania through cultivation of crown land, forest management, and by counteracting a famine before a suspected bad harvest. He completed the province's military allotment and was tasked with setting the kingdom's plan of defense for a coming war with Denmark. Denmark had a tense relationship with the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp to the south, which was allied with Sweden. Rehnskiöld advocated that the border provinces of the Swedish Empire would constitute its strongest defense; each province would be defended by its own allotted regiments. The eastern provinces were reinforced with Finnish allotted regiments and over 100 permanent forts, guarded by enlisted garrison regiments. For the kingdom to have a successful defense the Swedish Navy must have dominion over the Baltic Sea, to provide troop transports and maintain supply lines. Since the army was short of dragoon regiments, Rehnskiöld implored permission to set up his own regiment through recruitment, and, in 1700, he founded the Life Dragoon Regiment. Lieutenant-Colonel Hugo Johan Hamilton was appointed its second-in-command. Rehnskiöld wanted to make it an elite unit fighting at the King's side, and it would consist only of men from mainland Sweden. In Scania, Rehnskiöld was the owner of Allerup and Torup farms. He owned the largest collection of oxen in all of Scania; 112 pairs in total.[18][19] He was succeeded as Governor-General by Magnus Stenbock in 1705.[20]

On 17 January 1697, Rehnskiöld married Elisabeth Funck, daughter of the assessor in Bergskollegium Johan Funck. Rehnskiöld was thus brother-in-law to Carl Magnus Stuart, who was married to his wife's older sister Margaretha Funck. In 1699, a daughter was born to the couple, who died before she was one year old. Rehnskiöld then left Sweden to embark on the Great Northern War, reuniting with his wife on the spring of 1707 in the castle of Altranstädt.[21][22]

Great Northern War (1700–1709)

Campaign in Denmark and the Baltics

The Great Northern War began on 12 February 1700. The King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, Augustus II, crossed the Düna river with his Saxon troops and besieged the city of Riga in Swedish Livonia. Riga was defended by Governor-General Erik Dahlbergh. Simultaneously, King Frederick IV of Denmark and his Danish troops invaded Holstein-Gottorp and laid siege to Tönning on March.[23][24]

Throughout the Swedish Empire the allotted regiments were mobilized and ordered to march to southern Sweden. The standing army consisted of 77,000 men, of which 10,000 were sent to the Norwegian border and 16,000 were gathered in Scania to fight against Denmark.[25] Rehnskiöld was commander of the army's deployment in Scania, which he later commanded, and was appointed leader of the operational army headquarters, serving directly under the King. The Swedish ministry of foreign affairs, under Bengt Gabrielsson Oxenstierna, advised Charles XII to relieve Livland, but the King chose to first avert the Danish threat, and Rehnskiöld passed the King's decision to Oxenstierna.[26][24]

In mid-July 1700, the Swedish Army command decided to land Swedish troops on Zealand. The main landing would be concentrated in Køge Bugt south of Copenhagen under the command of Rehnskiöld, while a small unit would land at Humlebæk south of Helsingør, acting as a distraction. However, the landing at Køge Bugt was called off. Instead, Rehnskiöld and Carl Magnus Stuart planned the landing at Humlebæk, which would be carried out with the support of the Swedish battle fleet. The landing took place on 25 July. Rehnskiöld commanded the left wing of the Swedish landing forces while the King and Stuart commanded the right wing. The Danish defenders were quickly routed, and the Swedes established a bridgehead on Zealand. This forced Frederick IV to withdraw from the war on 8 August 1700 with the peace of Travendal.[27][28]

Following Denmark's withdrawal from the war, the Swedish Army reassembled in Scania at the end of August to be transported to the Baltic front. Shortly before, Charles XII was informed that Russian troops under Tsar Peter I had besieged the strategically important Swedish outpost of Narva in Estonia. The Swedish Army were shipped from Karlshamn to Pernau in Estonia on early October. Once informed about the Swedish landing, Augustus II ordered his troops to abandon the siege of Riga. With another threat stopped for the time being, Charles XII and Rehnskiöld left Pernau on 16 October and arrived at Reval on 25 October. At Wesenberg, east of Reval, Charles XII gathered all available Swedish units, a total of about 11,000 men. On 13 November the Swedish main army broke up and marched towards Narva. Many officers considered this venture too risky, since the Russian siege army was rumoured to number about 80,000 and the Swedish Army lacked supplies and reinforcements. After skirmishes with Russian reconnoitres the Swedes arrived at the outskirts of Narva on 20 November. Through reconnaissance the Swedes learned that the Russians, who were about 30,000 strong, had built a fortification system that stretched in a semicircle between the north and south sides of the city.[29][30]

Together with Quartermaster Lieutenant-General Gerdt Ehrenschantz and artillery commander Johan Siöblad, Rehnskiöld drafted a simple battle plan that was never written on paper. The Swedes would attack with two columns, consisting of both infantry and cavalry, against the central part of the fortification line. Each column would then move to the south and north along the line and roll up the Russian defense so that the Russian Army would be trapped in two pockets against the Narva River. The Swedish artillery would support their advance. Rehnskiöld himself took charge of the left column while general Otto Vellingk commanded the right. Rehnskiöld's column was split into two groups, one under Major-General Georg Johan Maidel and the other under Colonel Magnus Stenbock.[31][32][33][34][35]

In the afternoon of 20 November, the two Swedish columns advanced towards the Russian line. The Swedes, hidden by a heavy snowstorm that blew directly into the eyes of the Russians, breached the fortifications, causing a violent massacre and panic among the Russian troops. After a wild rout the Russian Army chose to surrender, and after negotiations were allowed to withdraw back to Russia. The Russians lost about 9,000 men during the battle, and their entire command was captured, while the Swedish casualties were estimated to be around 1,900 men. Peter I himself was not present at the battle, since he handed over the command of his army to Duke Charles Eugène de Croÿ, who became a prisoner of war.[36][37][38] Many European nations were greatly impressed with the Swedish victory and congratulated the King and his army.[39] Magnus Stenbock later praised Rehnskiöld for his efforts during the battle:

This is God's work alone, and if anything human had any part of it, it was the firm, immovable resolution once made by His Majesty, and the ripe dispositions of Lieutenant-General Rehnskiöld against the intent of others, which were done honestly. I can truly declare him general. Grant him life under God, he will be a great Captain, so much more as he is an honorable and faithful friend, adored by the whole army. I have so much more reason to venerate him, who through his instigation that day I came to command on the most difficult side as Major-General, of which I have the pleasure to call myself.

Campaign in Poland

The main Swedish army overwintered outside the town of Dorpat and the dilapidated Laiuse Castle. In the spring, the army was reinforced by regiments from the Swedish mainland, raising their numbers to 24,000 men. In June the army broke up and marched south to Riga to attack Augustus II and his combined Saxon-Russian army, which was estimated to 38,000 men. On 7 July the Swedish main army stood outside Riga, and Charles XII and Rehnskiöld planned to cross the Düna river right next to the city. Augustus II entrenched his troops along the river, but they were uncertain whether the Swedes were going to cross at Koknese or Riga, and decided to split their forces. Rehnskiöld drafted the battle plan together with Carl Magnus Stuart and Erik Dahlbergh. Dahlberg was tasked to obtain landing boats near Riga and construct floating batteries, embarked by infantry units that would land on the opposite beach and establish a bridgehead. A floating bridge had been constructed by Dahlbergh to transfer the cavalry across the river and pursue the Saxon troops. The cavalry was commanded by Rehnskiöld, while the infantry was commanded by the King accompanied by Lieutenant-General Bernhard von Liewen.[41][42]

On the morning of 9 July, 3,000 Swedish troops rowed towards the opposite beach. The Swedes torched some smaller boats and pushed them out into the river to obstruct the allies' view. However, because of strong currents, the floating bridge was destroyed and its repair was prolonged, forcing Rehnskiöld to improvise by transporting parts of his own Life Dragoon Regiment with rafts. The King's infantry established a bridgehead and repelled multiple Saxon attacks. Augustus II called a retreat and lost up to 2,000 men, while the Swedish casualties amounted to 500 men. The crossing was a success but became a strategic failure since the Swedes could not win a decisive victory over the Saxon troops.[43][42][44]

Having failed to defeat Augustus II in the Düna operation, Charles XII decided to carry out a military campaign on Polish territory to defeat Augustus' army, and secure his own back for an attack against Russia. In July 1702, Charles XII and his main army caught up with Augustus II at the village of Kliszów northeast of Kraków. He was eager to attack Augustus II, but on Rehnskiöld's advice, waited for reinforcements from Lieutenant-General Carl Mörner's division, which arrived on 8 July. At the same time, Augustus waited for the Polish cavalry, which arrived the following day. Together with Lieutenant-Generals Bernhard von Liewen and Jakob Spens, Rehnskiöld drafted the battle plan. Augustus had around 24,000 Saxon-Polish troops covered by dense forest and vast swamps on the Nida river. The artillery was stationed at a height between the two wings, while the Saxon center was placed behind the artillery. The Swedish Army consisted of 12,000 troops. The main Swedish force would move parallel to the Saxon front line and perform a flanking maneuver towards the Saxon right wing. The Swedish right wing, led by Rehnskiöld, would defend itself against the Saxon frontal assault, led by Field Marshal Adam Heinrich von Steinau, before the Saxon troops had the time to regroup in order to repel the Swedish main force.[45]

On the morning of 9 July, the Swedish troops advanced towards the Saxon front line. When the Polish cavalry began to attack the Swedish left wing and threatened to surround the main Swedish force, the Swedes were forced to regroup to face the Polish cavalry and managed to rout the cavalry. By ordering his troops to form squares, Rehnskiöld successfully resisted Steinau's frontal attack, whose troops were forced to withdraw. The Swedish main forces advanced into the Saxon camp, took control of the Saxon artillery, and threatened to encircle the Saxon center. Augustus II was forced to withdraw, and lost about 4,000 men, with Swedish losses were estimated at 1,100 men. Among the dead was Rehnskiöld's nephew Frans Anton Rehnskiöld, who was Captain of the Life Guards, and Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, who commanded the Swedish left wing in their attack.[46][47]

Charles XII failed to hunt down Augustus II's retreating army and Augustus II's defeat was once again not decisive, as he was able to withdraw and organize new troops. As a result, Charles XII and the main Swedish army operated around Poland to destroy Augustus II's Polish resources and his Saxon division, while also persuading various nobility factions in Poland who opposed Augustus II to depose him as King. In December 1702 Rehnskiöld was commissioned with four infantry and nine cavalry regiments, about 10,000 men, operating independently from the Swedish main army. He was tasked with securing the negotiations between the various noble factions in Warsaw, and to collect money and food from the immediate vicinity to supply the Swedish troops besieging the city of Thorn. He established headquarters near Piotrków Trybunalski, while his troops were mostly stationed in different locations in Greater Poland, where he kept a watchful eye towards the nobility factions fighting for Augustus II.[48] During his debriefings to the royal headquarters, Rehnskiöld exchanged command with Major-General Arvid Axel Mardefelt. In April 1703 Rehnskiöld was promoted to General of cavalry, elevating his prestige during his negotiations with the Polish nobility factions which included Prince James Louis Sobieski, magnate Hieronim Augustyn Lubomirski and Cardinal Michał Stefan Radziejowski. In February 1704 the Warsaw Confederation congregated and agreed to depose Augustus II as King of Poland, since he had lost much of his influence in the kingdom. Rehnskiöld was given the task of securing their deliberations and preventing the troops of Augustus II from advancing eastwards.[49][44]

War in Saxony

In the summer of 1705, Rehnskiöld received command of an army in Greater Poland, consisting of five infantry, three cavalry and five dragoon regiments: about 10,000 men in total. Rehnskiöld was tasked with protecting Charles XII and the Swedish main army's rear against Augustus II and his Saxon main army, who were mobilizing inside the Saxon border. The Saxon forces comprised a total of 25,000 men, reinforced by Russian auxiliaries and commanded by Field Marshal Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg. Rehnskiöld marched closer to the Saxon border along the Vistula river and established winter quarters at Poznań. In December he was appointed Royal Councillor and Field Marshal by Charles XII, but was not aware of this until he received a letter from the King in August 1706.[50][51][44]

The Swedish troops resumed their movements in mid-January 1706. Through reconnaissance and interrogation of Saxon prisoners and defectors, Rehnskiöld found out that the Saxons planned to conduct a twofold attack on his army: from the southwest by Schulenburg and from the northwest by a division led by Augustus II. Rehnskiöld moved quickly to attack Schulenburg's army and defeat it before Augustus II could arrive, despite being greatly outnumbered. On 31 January Rehnskiöld reached the village of Fraustadt near the Saxon border. Schulenburg's army was already there and occupied a strong position. Its center was formed of about 16,000 Saxon-Russian infantry, supported by 37 artillery pieces, with 4,000 Saxon cavalry units covering its flanks. Rehnskiöld had only 9,400 combatants, including 3,700 infantry units and 5,700 cavalry units. Outnumbering the Saxons in the number of cavalry units, he planned a risky pincer movement, comprising a weak center consisting of infantry units and some cavalry squadrons, and two strong cavalry wings, the right-hand one led directly by Rehnskiöld. The Swedish center would face the Saxon frontal assault, while the cavalry wings would attack the Saxon flanks with full force, drive them off, and then attack the Saxon center in the rear.[52][53][54]

Rehnskiöld gave the attack signal at noon on 3 February 1706. The battle of Fraustadt began with the two Swedish wings advancing faster than the center, making the Swedish battle line curved, which Schulenburg perceived as a sign of weakness. The Swedish wings, however, charged the Saxon flanks and drove off their cavalry. The Swedish wings encircled and enclosed the Saxon-Russian center, which soon disintegrated, forcing Schulenburg to retreat. Schulenburg himself managed to escape, but large parts of his army were cut down by the Swedish cavalry and the remnants were surrounded and captured. After two hours of battle, 7,377 men from Schulenburg's army had been killed and between 7,300 and 7,900 were taken prisoner; among these, about 2,000 were wounded. Of Rehnskiöld's troops, 400 were killed and 1,000 were wounded. Many of the Saxon prisoners were subsequently employed in the Swedish Army and formed a Bavarian regiment and a French and a Swiss battalion respectively.[55][56][57][58]

.jpg.webp)

Rehnskiöld's name was later tied to a massacre that was purported to have occurred shortly after the battle. According to testimony from a Lieutenant Joachim Matthiæ Lyth and Lieutenant-Colonel Nils Gyllenstierna, Rehnskiöld ordered the massacre of up to 500 Russian prisoners of war.[60]

His Excellency, General Rehnschiöld immediately formed a circle of dragoons, cavalry and infantry, into which all remaining Russians were gathered, approximately 500 men at large. Without any mercy in the circle, they were immediately shot and stabbed to death, they fell on top of each other like slaughtered sheep.

— Joachim Matthiæ Lyth, Excerpt from Lyth's diary.[60]

His order was condemned by Swedish historians such as Eirik Hornborg, Sverker Oredsson, and Peter Englund.[61][62][63] Other historians such as August Quennerstedt and Gustaf Adlerfelt considered that the massacre did not take place on Rehnskiöld's orders, but rather, might have occurred during the desperate situation in the final stages of the battle. Historians Henning Hamilton and Oskar Sjöström questioned even the existence of the massacre. Both considered that the other historians had misinterpreted or confused this event with the Swedish cavalry's pursuit of the broken Saxon-Russian infantry, who suffered enormous casualties.[62][64] Likewise, historian Jan von Konow questioned the certainty of Joachim Lyth's testimony.[64]

The victory at Fraustadt had a crippling effect in Denmark, Russia and Saxony, and caused shock waves around Europe. In France, the victory was celebrated, and Prussian policy immediately became friendlier to the Swedes.[65] In June the same year, Rehnskiöld was made Count (in 1719, the count's branch of the Rehnskiöld family was introduced at the House of Nobility under number 48).[22] With the main Saxon army defeated, the Swedish Army had the opportunity to move into Saxony and force Augustus II out of the war. In August, Charles XII reunited with Rehnskiöld's army. The joint army moved through Imperial Silesia, and by September, the Swedes had successfully occupied Saxony without resistance. The Treaty of Altranstädt (1706) was concluded between Sweden and Saxony on 14 September. Under Swedish terms, Augustus II was forced to break all ties with his allies, renounce his claims to the Polish crown, and accept Stanisław Leszczyński as the new King.[66][67]

The Swedish Army stayed for one year in Saxony, seizing substantial taxes from the Saxon estates for its maintenance. During this time, Charles XII's headquarters in Altranstädt became a center for festivities and banquets, as well as one of the focal points of European politics. Princes, diplomats and military personnel from all over Western Europe traveled to Altranstädt to meet the victorious King and his troops. The renowned English General, the Duke of Marlborough, who was one of the visitors persuaded Charles XII not to interfere in the War of the Spanish Succession, which took place simultaneously with the Great Northern War.[68] Determined, Charles XII mustered his army to go east towards his final opponent, Tsar Peter and Russia.[69][67]

Campaign in Russia

The Swedish Army left Saxony on August 1707 to march east towards Russian territory. The army was largely newly recruited and well-equipped, numbering about 40,000 men. Rehnskiöld acted as Field Marshal and stood closest to the King at its high command. Rehnskiöld and the army command were unaware of Charles XII's plans for the campaign, which the King kept to himself, but agreed upon a preliminary march towards Russia's capital Moscow, where Peter I had gathered most of his forces. Charles XII ordered the commander of the "Army of Courland" in the Baltic provinces, General Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt, to join the main army in the march against Moscow. Lewenhaupt and the Army of Courland were also tasked with obtaining supplies and wagons for onward transport to the Swedish main army. Awaiting Lewenhaupt's troops, the main army advanced slowly towards the Russian border. At the end of January 1708, they arrived at Grodno, which was occupied by 9,000 men of Peter I's army. Charles XII and Rehnskiöld attacked with 800 cavalry units, and the Russian troops withdrew after a short but fierce battle. Later in the evening, Russian troops sneaked into the city to surprise the Swedes; Rehnskiöld ended up in the middle of the attacking troops, but was not recognized because of the dark sky and managed to get to safety. The attack was repelled, and the Russians were forced to retreat. Later in the year, during the crossing of the Vabitj River at the town of Holowczyn in July 1708, the Swedish vanguard encountered a Russian army in fortified positions on the opposite shore. In the battle of Holowczyn, Charles XII commanded the infantry while Rehnskiöld commanded the cavalry. The Russian troops under Field Marshal Boris Sheremetev and Prince Alexander Danilovich Menshikov were pushed back after eight hours of struggle; however the Russian Army managed to escape mostly intact so the battle was not a decisive strategic victory.[70][71]

Following the battle of Holowczyn, Charles remained for nine weeks in Mogilev and the nearby areas to the east, between the Dnieper and its tributary Sozh, awaiting Lewenhaupt's late arrival. Lewenhaupt's mission was exceptionally complicated, and halfway to the main army he was intercepted by a Russian army under Peter I's personal command. The resulting battle at Lesnaya on 29 September ended in a draw, with both armies suffering heavy losses. In order to prevent the supply train from falling into Russian hands, Lewenhaupt decided to burn the wagons and the bulk of the supplies, continuing his march with half of his troops. On 23 October, Lewenhaupt eventually united with the main army, but only with 6,500 men and without the necessary supplies.[72][73]

Throughout the campaign, Rehnskiöld held a fierce rivalry with the Marshal of the Realm, Count Carl Piper,[lower-alpha 3] who had accompanied Charles XII as chief of the perambulating chancellery since 1700. The tense relationship between Rehnskiöld and Piper dated back to the Swedish Army's march on Saxony. Both men desired the King's favor: as the senior civilian army official Piper sought to persuade the King not to make reckless actions, whilst Rehnskiöld, as second-in-command of the army supported the King's offensive plans. The antagonism between the two, in combination with their fiery temperament and pride in their own abilities, made them unable to reason with each other without an intermediary, a role usually filled by Quartermaster General Axel Gyllenkrok. Their relationship would eventually cause discord and division within the Swedish headquarters, as well as hopelessness and anxiety within the army.[75]

Rehnskiöld discussed which road the army would take from Tatarsk with Gyllenkrok. The army suffered from lack of food supplies and had to move to areas where they could resupply. Peter I had adopted scorched earth tactics, rendering the Swedish march against Moscow ever more difficult. During a council of war, Charles, Rehnskiöld, Piper and Gyllenkrok concluded that the army would go south to Severia, in the direction of Little Russia. There the Swedes would be able to establish reliable winter quarters and receive supplies and reinforcements through Charles' alliance with Ivan Mazepa, Hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.[76][77]

Upon learning about Mazepa's alliance with Charles XII, Peter I sent an army under Prince Menshikov to conquer and burn down Mazepa's capital Baturyn. The Cossacks who did not support Mazepa chose Ivan Skoropadsky as the new Hetman on 11 November 1708. Thus, Mazepa lost much of his support in the country and brought the Swedes only a few thousand Cossacks, without the great army and the rich food resources he previously promised. During The Great Frost of December 1708 thousands of Swedish and Russian soldiers succumbed to the cold. The Swedish Army set up camp around Gadyat in early December. Near the town was the fortress of Veprik, which was occupied by a Russian garrison of 1,500 men and blocked the Swedish advance. Charles XII decided that Veprik should be conquered. The assault, on 7 January 1709, was led by Rehnskiöld. He planned that Swedish cannons would bombard the fortress ramparts, after which three columns of 3,000 men would climb the ramparts from different directions using storm ladders and cut down the Russian defenders. The first assault failed, as the defenders used several methods to slow down and fend off the Swedish columns. During the second assault, Rehnskiöld was hit in the chest by a bullet from a falconet, forcing him to hand over command to Major-General Berndt Otto Stackelberg. This assault was also fruitless, but the two sides agreed upon a truce. Since the Russian garrison had used almost all their ammunition, their Commandant chose to surrender. The Swedish losses counted to 1,000 men killed and 600 wounded. Rehnskiöld recovered slightly after six weeks, but his shrapnel injury would never be fully healed.[78][79]

The Swedish Army remained in the areas around Veprik until late February. They marched south to a strong position between Dnieper's tributaries Vorskla and Psel, to gain reinforcements from Poland and Mazepa's Cossacks. Rehnskiöld was commissioned to stay with nine infantry and cavalry regiments in the areas around Gadyat and Veprik, shielding the main army against attacks from the north. Rehnskiöld's troops reunited with the main army in early March and at the southern part of Vorskla, the Swedish Army arrived at the fortified city of Poltava. In order to occupy the Russians and lure them into the field, Charles XII laid siege to Poltava in May 1709. The city was defended by a 4,200-man garrison. Peter I marched to relieve the city with an army of 74,000 Russian regulars and irregulars.[80] During a reconnaissance on 17 June, Charles XII was struck by a stray bullet, injuring his foot badly enough that he was unable to stand. News of his injury tempted the Tsar to dare a field battle. Peter I crossed the Vorskla River and constructed a fortified camp north of Poltava. Between the Russian and Swedish troops was a wide-open field, where two woods formed a passage which the Russians defended by building six redoubts across the gap. In addition, Peter I ordered another four redoubts to be built so that the ten redoubts would form a T-shaped barricade, providing flanking fire against a Swedish advance. Despite his injury, Charles XII would not neglect an opportunity to put up a battle against the Tsar, and commanded Rehnskiöld to attack.[81][82]

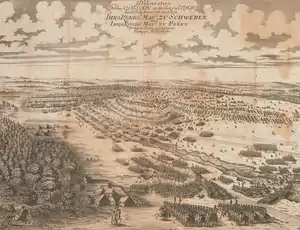

Battle of Poltava

The opposing forces at Poltava comprised about 16,000 Swedish soldiers and 40,000 Russian. Rehnskiöld replaced the King as commander-in-chief; Lewenhaupt commanded the infantry and Major-General Carl Gustaf Creutz the cavalry. The battle plan was constructed by Rehnskiöld in consultation with the King, while Gyllenkrok established the formation plan. The 8,170 strong Swedish infantry was divided into four columns, which would carry out a surprise attack against the Russian redoubts before dawn and bypass them. The 7,800 strong Swedish cavalry would follow the infantry, divided into six columns. After the infantry bypassed the redoubts, they would march to the wide field in front of the Russian field camp, to a position at a ford near the village of Petrovka and northwest of Peter's fortified army, while simultaneously, the Swedish cavalry would drive off the Russian cavalry. From that position, the gathered Swedish Army would march to the right and form itself into battle formation. If the maneuver succeeded, Peter's fortified army would be trapped in their own camp, with the steep river bank behind them and the Swedish Army in front of them, blocking their line of retreat at Petrovka. If they would not accept the Swedes' challenge, they would eventually starve to death. The four infantry columns would be commanded by Major-Generals Axel Sparre, Berndt Otto Stackelberg, Carl Gustaf Roos and Anders Lagercrona. The King accompanied the eastern column on the left wing in a stretcher.[83][84][85]

Shortly before midnight on 28 June, Rehnskiöld ordered his troops to decamp and advance towards the Russian redoubts in the cover of darkness. Disorder arose in some of the columns, with Rehnskiöld having a vicious exchange with Lewenhaupt:

Where the hell are you up to? No one should witness this; don't you see that everything is in confusion? [...] Yes, you are, you worry about nothing. I need no help nor any use from you. I had never imagined you to be like that, I had expected much more of you, but I see it is for nothing.

— Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld[86]

The Russians discovered the Swedes' presence and sounded the alarm, and the Swedes lost the element of surprise. After a council of war between the King, Rehnskiöld and Gyllenkrok, Rehnskiöld ordered the infantry columns to regroup and continue the advance. It was already daylight, and the Swedes discovered the entire Russian cavalry stationed behind the redoubts. The cavalry tried to storm the Swedish columns but the Swedish cavalry fended them off; the Russians were forced to retreat and were pursued by the Swedish cavalry. With the field empty, the Swedish infantry marched towards the Russian redoubts, the foremost of which were conquered after a short battle. The attacks against the other redoubts caused large casualties among the columns, especially for Ross’ column, which was forced to retreat to a nearby forest and would later surrender. In the meantime, the other columns passed the remaining redoubts and marched to the open field in front of the Russian field camp, but Rehnskiöld had already lost one third of his infantry. At the same time, the Swedish cavalry had chased the Russian cavalry past the field camp and further north. The Russian cavalry were close to being driven off towards a deep sink in the terrain covered by stony wetlands, when Rehnskiöld ordered the Swedish cavalry to interrupt the hunt and re-assemble with the infantry.[87][88][89]

At nine o'clock, the Russian infantry marched out from the fortified camp and formed into battle formation. Prior to the final battle, 4,000 Swedish soldiers gathered in a line against 22,000 Russian soldiers who were set up into two lines. Rehnskiöld ordered Lewenhaupt to attack the Russian lines with his infantry, but since the Swedish cavalry did not arrive in time, the Swedish infantry was broken and the remnants routed. The King, Lewenhaupt and most of the cavalry escaped, united with the siege troops and the baggage train, and marched south along the Vorskla River. Rehnskiöld, Piper and the survivors from the infantry were captured by the Russians. 6,900 Swedes were killed or wounded in the battle, and 2,800 were captured. The Russians lost 1,345 men with 3,290 wounded.[90][88][91]

A couple of days after the battle, Lewenhaupt and the 20,000 soldiers and non-combatants remaining from the Carolean Army, surrendered to Prince Menshikov at the village of Perevolochna at the ford of the Dnieper. The King, Mazepa and about 1,000 men managed to cross the river and headed to the Ottoman Empire, where Charles stayed for several years before returning to Sweden at the end of 1715. With the main Swedish army destroyed, both Denmark-Norway and Saxony-Poland returned to the war against Sweden. Hannover and Prussia also joined the alliance against Sweden, and together with Russia, the countries attacked the Swedish dominions around the Baltic Sea. The battle of Poltava and the subsequent surrender marked the beginning of Sweden's final defeat in the war.[92][93][94][95]

Rehnskiöld's failure as commander during the battle has been a subject of debate among historians. They stated that Rehnskiöld was in mental imbalance, as evidenced by his scolding of Lewenhaupt, his second-in-command. Psychologically, Rehnskiöld's task as commander-in-chief was stressful and almost impossible due to the King's presence and oversight. von Konow raises two major mistakes Rehnskiöld made during the battle. The first was that he organized no reconnaissance of the Russian redoubts that were built the night before the battle and had not informed his subordinates about his plan of attack, causing great confusion in the Swedish high command. The second was his decision to stop the Swedish cavalry's pursuit of the retreating Russian cavalry, which was close to being driven against steep gorges north of the battlefield. Historians have speculated about the reason for this order. Opinions have differed from approval, since Rehnskiöld would not take the risk of losing contact with his cavalry during the battle's decisive point, and strongly condemning, because the elimination of the Russian cavalry could have determined the entire battle in favor of the Swedes.[96]

Prisoner of war (1709–1718)

Shortly after the battle, Rehnskiöld and the other captive Swedish officers were brought to the Russian camp. Rehnskiöld, Piper and four Swedish generals were taken to Menshikov's tent, where they surrendered their swords to the Tsar. Peter I asked Rehnskiöld about the King's health, since the Russians believed he was among the dead, and Rehnskiöld replied that he believed the King was alive and well. Pleased with his reply, Peter returned him his sword. Later the Tsar ordered a banquet with the captured Swedish generals, asking several questions of Rehnskiöld and the other generals, and proposing a toast to his Swedish "teachers in the art of war".[97][98]

During late autumn 1709, Rehnskiöld and the captured Swedish army were transported to Moscow, where Peter I arranged a massive victory parade on 22 December. The prisoners of war were arranged in ranks, with Rehnskiöld and Piper walking among the last. After the parade, the Swedish prisoners were distributed to cities and prison camps around Russia. Rehnskiöld and Piper moved into Avram Lopuchin's house in Moscow. During a dinner Rehnskiöld had an argument with Piper and Lewenhaupt, where Piper criticized Rehnskiöld's leadership during the battle of Poltava and blamed him for the loss. Piper's insults provoked Rehnskiöld to the point of violence. Lewenhaupt and Gyllenkrok separated them, and Rehnskiöld began accusing Lewenhaupt and the other officers for expressing criticism towards Charles XII:[99][100]

Here are those who dare to criticize the actions of the Lord (Charles XII), but I shall force you to remember: that you will be satisfied with the Lord's actions.

— Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld[101]

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_15375.tif.jpg.webp)

A few days later Lewenhaupt proposed, first to Piper and later to Rehnskiöld, that they should reconcile so that their hostile relationship would not affect the other Swedish officers. In the presence of Swedish generals and colonels, Rehnskiöld and Piper settled their differences. Both remained in Moscow and established a collaboration to help the Swedish prisoners of war and satisfy their interests. With the approval of the Russian authorities they established a management office in the city, through which all contact with the Swedish authorities was routed. They worked hard to raise money for the Swedish prisoners through funds sent from the State Treasury in Stockholm; however, over the years these transfers became increasingly sporadic.[99][100][102]

Due to the lack of support from the Swedish authorities for their captured countrymen, Rehnskiöld and the Swedish officers were forced to request allowances from the Tsar in 1714. However, the Tsar decided to exacerbate the conditions of subsistence for the Swedish officers as a punishment for Rehnskiöld's and Piper's earlier inflexibility before the Senate in Saint Petersburg, where threats of reprisals were required to compel them to sign the exchange act between the Swedish Commandant Nils Stromberg and the Russian General Adam Veyde, a matter in which they had no authority. The Tsar's resentment over reports of the treatment of Russian prisoners of war in Sweden was a contributing factor to this decision. Piper was imprisoned in Shlisselburg Fortress, where he fell ill and died in 1716.[103] Rehnskiöld was forced to take care of the management office by himself. He wrote letters of complaint to the Swedish authorities regarding the misery of the Swedish prisoners around Russia. With the rapid spread of pietism among the prisoners Rehnskiöld formed an ecclesiastical board in Moscow, from which captive chaplains were sent out to the Swedish prison camps. Rehnskiöld himself decided the biblical texts for the four set days for intercession.[104]

My God knows what anxiety I have been carrying around during this long captivity, and noticed me being far away from Your Majesty's gracious eyes, and my most sincere courtship. But my only concern and work has been to serve the other unfortunate poor prisoners, those I supported from my poor estate, that is nowadays almost empty, and from time to time I must expect an unruly misfortune falling over me, because my protests rush back to me. Your Most Gracious Majesty, I thus pray that You do not keep Your gracious hand away from me, so that I may not perish in this misery, but with Your gentleness, the one I always enjoyed undeservedly, save me from this danger.

— Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld, From Rehnskiöld's letter dated 7 January 1715, which he sent to Charles XII regarding his arrival at Swedish Pomerania.[105]

After a long time without any effort from the Swedish side, the matter of getting Rehnskiöld exchanged from captivity was raised in the spring of 1718, when Russia commenced peace negotiations with Sweden in Lövö village on Vårdö in Åland. Rehnskiöld came to be involved in the matter of succession in Sweden on the initiative of Georg Heinrich von Görtz from Holstein-Gottorp, who had served as Swedish "grand-vizier" since 1716 and was responsible for the peace talks. Charles XII had no heirs, so Görtz wanted Rehnskiöld on his side to strengthen his own position in the Holstein Party, in which Görtz held great influence. Görtz and his party wanted to make Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp heir to the Swedish throne, in order to counteract the pressure from the Hessian party, whose choice for heir to the throne was landgrave Frederick of Hesse-Kassel, Prince consort to Charles XII's sister Princess Ulrika Eleonora. After pressure from the Swedish side, Peter I gave the order on 17 September to send Rehnskiöld to Lövö, where he would be exchanged with Major-General Ivan Trubetskoy and Count Avtonom Golovin. Rehnskiöld arrived at Lovö on 14 October, where he entrusted Görtz's secretary, Andreas Stambke, to convince Charles Frederick to marry a daughter to Peter I in order to bolster relations between Sweden and Russia.[lower-alpha 4] On 30 October the exchange was finalized and Rehnskiöld was finally released.[108]

The last years (1718–1722)

Immediately after his release, Rehnskiöld went to Stockholm and met with Görtz. Later, Rehnskiöld went to Charles XII's headquarters in Tistedalen in Norway, where the King commenced his second Norwegian campaign by laying siege to the fortress of Fredriksten. Rehnskiöld arrived at the end of November 1718, and the reunion with the King was claimed as "one of his last joys in life".[109] Both had a long conversation on 28 November, regarding the current operational situation in Norway and the peace talks with Russia, about which Rehnskiöld obtained fresh information. Two days later, on the evening of 30 November, Charles was shot by a projectile and immediately killed. The King's sudden death forced Prince Frederick, appointed Generalissimo of the army, to call for a council of war, where the Swedes decided that the army must abandon the siege and return to Sweden. The report on the death of Charles XII was signed by Rehnskiöld and Field Marshal Carl Mörner and sent to the Privy Council in Stockholm. Furthermore, Frederick ordered the arrest of Görtz on 2 December, since the Hessian party sought to seize the upper hand in the matter of succession, which they gained with the death of Charles XII. Görtz was taken to Stockholm, where he was sentenced to death at the Svea Court of Appeal and beheaded on 19 February 1719. With Görtz's death, the negotiations with Russia were discontinued and the war went on for another three years.[110][95]

Another council of war took place in Strömstad on 14 January 1719. The reason for this was that a considerable sum of 100,000 riksdaler arrived from the war commissioner, and Prince Frederick wanted to distribute the money to the high command of the army, in order to win influential votes in the matter of succession. Rehnskiöld himself received 12,000 riksdaler, which he saw as a recognition for his time in Russian captivity. Rehnskiöld later entered the Privy Council in Stockholm. When the soldiers carrying the King's body arrived in Stockholm on 27 January, they were received by the council members Rehnskiöld, Arvid Horn and Gustaf Cronhielm. On 26 February Charles XII was buried in the Riddarholm Church; Rehnskiöld carried the royal spire during a long procession from Karlberg Palace to Riddarholmen.[111][112]

Due to the kingdom's critical state of weakness, Rehnskiöld was appointed commander in western Sweden to protect these regions from Danish attacks. Rehnskiöld travelled between Uddevalla and Gothenburg for inspection, strengthening the defenses in the cities and fortresses in Bohuslän and Scania. On 10 July, Danish forces landed at Strömstad, and a Danish-Norwegian main army of 30,000 men crossed the border at Svinesund and advanced south without resistance. Shortly after, Strömstad was taken and Frederick IV set up his headquarters there. In Bohuslän, Rehnskiöld had 5,000 men at his disposal and ordered them to burn down supply depots to prevent them from falling into Danish hands. He gathered his troops and fortified his position in Uddevalla, with the intent to defend the road connections towards Vänersborg and Dalsland. Rehnskiöld later learned about Commandant Henrich Danckwardt's surrender of Carlsten Fortress and decided to stay in Uddevalla despite the threat of being cut off by Danish forces, who could be landed north of Gothenburg. The Danish-Norwegian army in Strömstad, however, returned to Norway at the end of August. Rehnskiöld proceeded to Scania and defended it from an invasion threat. On 28 October 1719, an armistice was agreed with Denmark, and a peace treaty was signed in Frederiksborg on 3 July 1720.[113][114][115]

|

Promotions

|

On 30 August 1721, following pressure from the Russians, the war was finally concluded by the Treaty of Nystad between Sweden and Russia. The Russians raided the east coast of Sweden since 1719. After the peace, Sweden ceased to be a major power in Europe. When Ulrika Eleonora was appointed Sweden's ruling queen in 1719, she wanted her husband Frederick to become her co-ruler, but this was rejected by the Riksdag of the Estates. In 1720 she decided to step down as ruling queen, and on 24 March 1720, Frederick was appointed King. He was crowned Frederick I on 3 May in Stockholm, and as the oldest member of the Privy Council, Rehnskiöld assisted archbishop Mattias Steuchius in placing the crown upon Frederick's head. Rehnskiöld participated in the Riksdag meetings between 1719 and 1720, including Council assemblies, but made no further public appearances.[116][117]

In January 1722, Frederick I summoned Rehnskiöld to Kungsör. Rehnskiöld fell ill during the journey and was taken to Läggesta Inn outside of Mariefred. Having high fever and spitting blood, his declining health indicated that he was suffering from his old shrapnel injury from Veprik. He died on 29 January the same year, and with his death, both the noble and the count's branch of the Rehnskiöld family was extinguished. The funeral took place on 15 March at Storkyrkan in Stockholm.[118] The officiant was Chaplain Jöran Nordberg, who had followed Rehnskiöld and the army from 1703 to 1715.[116][117][119] Rehnskiöld's widow, Elisabeth, married Imperial Count Erasmus Ernst Fredrik von Küssow in 1724, and died on 23 November 1726.[22]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The spelling of his last name varies in different works between Rehnsköld, Rehnskiöld, Rehnschöld, Rehnschiöld, and Rehnschiöldt.[1]

- ↑ In 1641, Dahlbergh found employment as scribe to Gerdt Rehnskiöld, who at the time was the senior accountant for Pomerania and Mecklenburg. Rehnskiöld initially treated Dahlbergh harshly, but Dahlbergh soon gained his confidence and was given several important assignments.[9]

- ↑ With contemporary titles, Carl Piper could be characterized both as Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs.[74]

- ↑ Charles Frederick married Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna, elder daughter of Peter I.[106] Their son Charles Peter Ulrich became Charles Frederick's successor as Duke of Holstein-Gottorp in 1739 and was made Russian Tsar as Peter III.[107]

References

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 15

- ↑ "Rehnskiöld nr 270". Adelsvapens genealogi Wiki (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- 1 2 Rosander (2003), p. 262

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 14-15

- 1 2 Palmgren (1845), p. 48

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 18−23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Konow (2001), pp. 24−27

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 262−263

- ↑ Nordisk Familjebok – The Owl Edition, p. 1090

- 1 2 3 Palmgren (1845), p. 49

- 1 2 3 4 Rosander (2003), p. 263

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 28−31

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 32−38

- ↑ Åberg (1998), pp. 29-30

- 1 2 3 Konow (2001), pp. 39-44, 48

- ↑ Sjöström (2009), p. 91

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 41, 44-47

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 51-57

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 263−264

- ↑ Eriksson (2007), p. 167

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 49−50

- 1 2 3 "Rehnskiöld nr 48". Adelsvapens genealogi Wiki (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 60

- 1 2 Rosander (2003), p. 264

- ↑ Liljegren (2000), p. 76

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 58−60

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 60−63

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 265

- ↑ Laidre (1996), pp. 140–145

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 64−66

- ↑ Laidre (1996), pp. 146–153

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 68−69

- ↑ Eriksson (2007), pp. 66−67

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 267

- ↑ Hjärne (1902), p. 99

- ↑ Laidre (1996), pp. 146–171

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 71

- ↑ Eriksson (2007), pp. 67−68

- ↑ Laidre (1996), pp. 177–178

- ↑ Eriksson (2007), pp. 72−73

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 73−74

- 1 2 Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 268−273

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 74−75

- 1 2 3 Rosander (2003), p. 269

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 75−78

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 78−80

- ↑ Hjärne (1902), p. 165−166

- ↑ Hjärne (1902), p. 197

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 81−83

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 83−84, 88

- ↑ Sjöström (2008), pp. 74−80

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 84−85

- ↑ Sjöström (2008), chap. 8

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 269−270

- ↑ Sjöström (2008), chap. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 & 15

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 85−87

- ↑ Palmgren (1845), p. 51

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 271

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 88

- 1 2 Quennerstedt (1903), p. 31

- ↑ Englund (1988), p. 92

- 1 2 Sjöström (2008), pp. 288−290

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 90−93

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 92−94

- ↑ Sjöström (2009), pp. 264−266

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 96−97

- 1 2 Sjöström (2009), chap. 16

- ↑ Bain (1895), pp. 109−111

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 97−98

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 99−100, 103−105

- ↑ From (2007), pp. 50, 77−78, 141−163

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 100−101

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 287−293

- ↑ Konow (2002), p. 95

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 95−96, 113−115

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 101−102

- ↑ Åberg (1998), pp. 97-99

- ↑ From (2007), pp. 251−255

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 106−109

- ↑ Moltusov (2009), p. 93

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 110−112, 115−118

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 295–296

- ↑ Massie (1986), pp. 492−493

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 296–297

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 120−122

- ↑ Englund (1988), p. 101

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 297–299

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 123−126

- ↑ Massie (1986), pp. 494−500

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 302–303

- ↑ Massie (1986), pp. 501−506

- ↑ Ericson Wolke (2003), pp. 303–304

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 127−131

- ↑ Massie (1986), pp. 508−524

- 1 2 Rosander (2003), p. 273

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 126−127, 131−133

- ↑ Massie (1986), pp. 506−507

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 134

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 135−137

- 1 2 Norrhem (2010), pp. 133−139

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 135

- ↑ Åberg (1999), pp. 141−144

- ↑ Norrhem (2010), pp. 175−176

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 137−138

- ↑ Konow (2001), p. 139

- ↑ Wetterberg (2006), pp. 407, 410

- ↑ Britannica's editorial staff. "Peter III - Emperor of Russia". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 140−141

- ↑ Hatton (1985), p. 560

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 141−144

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 144−145

- ↑ Wetterberg (2006), p. 279

- ↑ Konow (2001), pp. 145−146

- ↑ Kuylenstierna (1899), pp. 38−40, 58−59

- ↑ Wetterberg (2006), p. 317

- 1 2 Konow (2001), pp. 146−147

- 1 2 Palmgren (1845), p. 57

- ↑ Åstrand (1999), p. 155

- ↑ Rosander (2003), p. 274

Works cited

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1895), Charles XII and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire, 1682–1719, New York: G.P. Putnam's sons, ISBN 978-1-5146-3268-0

- Englund, Peter (1988), Poltava: Berättelsen om en armés undergång [The Battle that Shook Europe: Poltava and the Birth of the Russian Empire] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Atlantis, ISBN 91-7486-834-9

- Ericson Wolke, Lars; Iko, Per (2003), Svenska slagfält [Swedish battlefields] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, ISBN 91-46-21087-3

- Eriksson, Ingvar (2007), Karolinen Magnus Stenbock [Carolean Magnus Stenbock] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Atlantis, ISBN 978-91-7353-158-0

- From, Peter (2007), Katastrofen vid Poltava - Karl XII:s ryska fälttåg 1707-1709 [The disaster at Poltava - Charles XII's Russian campaign 1707-1709] (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska Media, ISBN 978-91-85377-70-1

- Hatton, Ragnhild Marie (1985), Karl XII av Sverige [Charles XII of Sweden] (in Swedish), Köping: Civiltryck, ISBN 91-7268-105-5

- Hjärne, Harald (1902), Karl XII. Omstörtningen i Östeuropa 1697-1703 [Charles XII. The overthrow of Eastern Europe 1697-1703] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Ljus förlag

- Konow, Jan von (2001), Karolinen Rehnskiöld, fältmarskalk [Carolean Rehnskiöld, Field Marshal] (in Swedish), Stockholm: J. von Konow, ISBN 91-631-1606-5

- Kuylenstierna, Oswald (1899), Striderna vid Göta älfs mynning åren 1717 och 1719 [The skirmishes at the mouth of Göta älv between 1717 and 1719] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Norstedt

- Laidre, Margus; Melberg, Enel (1996), Segern vid Narva: början till en stormakts fall [The victory at Narva: the beginning of the end of a great power] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, ISBN 91-27-05601-5

- Liljegren, Bengt (2000), Karl XII: en biografi [Charles XII: a biograpfy] (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska Media, ISBN 91-89442-65-2

- Massie, Robert K. (1986), Peter den store: hans liv och värld [Peter the Great: His Life and World] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Bonniers, ISBN 91-34-50718-3

- Moltusov, Valerij Aleksejevitj (2009), Poltava 1709: Vändpunkten [Poltava 1709: The turning point] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek, ISBN 978-91-85789-75-7

- Norrhem, Svante (2010), Christina och Carl Piper: en biografi [Christina and Carl Piper: a biography] (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska media, ISBN 978-91-86297-11-4

- Palmgren, Sebell (1845), Biographiskt lexicon öfver namnkunnige svenska män: Tolfte bandet [Biographical dictionary of well-known Swedish men: Volume Twelve] (in Swedish), Uppsala: Wahlström & Widstrand

- Quennerstedt, August (1903), Karolinska krigares dagböcker jämte andra samtida skrifter / 2. J. Lyths & L. Wisocki-Hochmuths dagböcker [Diaries of Carolean warriors along with other contemporary writings / 2. J. Diaries of Lyth & L. Wisocki-Hochmuth] (in Swedish), Lund

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rosander, Lars (2003), Sveriges fältmarskalkar: svenska fältherrar från Vasa till Bernadotte [Sweden's field marshals: Swedish commanders from Vasa to Bernadotte] (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska media, ISBN 9189442059

- Sjöström, Oskar; Nilsson, Bengt (2008), Fraustadt 1706: ett fält färgat rött [Fraustadt 1706: a field tinted with red] (in Swedish), Lund: Historiska media, ISBN 978-91-85507-90-0

- Wetterberg, Gunnar (2006), Från tolv till ett: Arvid Horn (1664-1742) [From twelve to one: Arvid Horn (1664-1742)] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Atlantis, ISBN 91-7353-125-1

- Åberg, Alf (1998), Av annan mening: karolinen Axel Gyllenkrok [A different opinion: carolean Axel Gyllenkrok] (in Swedish), Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, ISBN 91-27-07251-7

- Åstrand, Göran (1999), Här vilar berömda svenskar [Here rests famous Swedes] (in Swedish), Bromma: Ordalaget, ISBN 91-89086-02-3