Carlos Fitzcarrald | |

|---|---|

Fitzcarrald at age 30. | |

| Born | Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald López 6 July 1862 |

| Died | 9 July 1897 (aged 35) |

| Nationality | Peruvian |

| Occupation | Rubber baron |

| Spouse |

Aurora Velazco (m. 1888) |

Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald López (6 July 1862 – 9 July 1897)[lower-alpha 1][2] was a Peruvian rubber baron. He was born in San Luis, Ancash, in a province which was later named after him. In the early 1890s, he discovered the Isthmus of Fitzcarrald, which was a portage route that allowed transportation from the Ucayali River into the Madre de Dios River basin. Fitzcarrald became known as the "King of Caucho" due to his success during the rubber boom.[lower-alpha 2] His enterprise exploited and enslaved Asháninka, Mashco-Piro, Harákmbut, Shipibo-Conibo and various other native groups, which were then dedicated to the extraction of rubber. Fitzcarrald drowned in a river accident on the Urubamba River in 1897, along with his Bolivian business partner Antonio de Vaca Díez.

Early life

Fitzcarrald, born as Isaís Fermín Fitzgerald, was the eldest son of an Irish-American sailor who later became a trader and married a Peruvian wife.[3][4][5][lower-alpha 3] Both his father[7] and grandfather were American sailors. Williams Fitzgerald, the grandfather, was the captain of a sailboat, and he drowned in a shipwreck.[8] His son, Williams Fitzgerald Jr. migrated to Peru and settled down in San Luis de Huari.[5][9] There he met Fermín Lopez, as well as his daughter, Esmeralda Lopez, who Fitzgerald fell in love with and married. The marriage resulted in seven children in total,[5] whose names were: Isaís Fermín, Rosalía, Lorenzo, Grimalda, Delfin, Fernando, and Edelmira.[10] He focused on the education of his firstborn Isaís, ensuring that his son went to well-known schools in the country.[11][12]

Isaís was a distinguished student,[5] and he was guided by his father's desire that he would become a sailor, specializing in naval engineering. Williams planned to send his firstborn to a nautical school in the United States to further his education around 1878.[13] Before this, Williams encouraged his son to take a trip along the Marañon to sell merchandise. The trip allowed Isaís to make a strong profit off of the cargo, and familiarize himself with the unexplored region of Peru. During the business venture, he was stabbed after confronting someone in a bar. The wound was so bad that local newspapers reported that he had died. His father paid for the medical expenses but suffered from grief. After Isaís recovered, he travelled to find better treatment, and on the way back, he found out his father had passed away.[5] After gathering blessings from the family, Isaís moved away from his hometown with his father's maps.[14][12]

Isaís ventured to Cerro de Pasco to join the military after finding out a war with Chile had broken out. He ran into a group of natives, tied up by soldiers who were taking them to Pasco as 'volunteers.'[5] Isaís protested, demanding the group of soldiers release the captives, who were complaining about mistreatment. The soldiers asked him to produce identification, but he was not a citizen and had left baptismal and school certificates at home. He was arrested after the soldiers found his father's maps, accusing him of being a Chilean spy.[5][12][15] There was no proof of identification for months until the day he was supposed to be executed. A man referred to as Fray Carlos was supposed to administer the last rites. The two had previously met in San Luis. Carlos didn't recognize Isaís at first on account of sickness and weakness but recognized his story. During a confession, Carlos was able to verify that he was the first-born son of Williams Fitzgerald Jr.[12] The Fray immediately declared under oath that the prisoner indeed was Isaís Fermín Fitzcarrald, and this led to his release.[5] Isaís later added Carlos to his name on account of Fray Carlos saving his life.[16][17]

On the advice of Fray Carlos, Isaís decided to travel to Loreto to seek "the happiness that the civilized had denied him."[18] Author Jean-Claude Roux states that Isaís went to Loreto with the hope of making a fortune.[5] Isaís disappeared for 10 years in the jungle without a historical trace, and multiple rumors tried to explain his absence.[5][12] In 1888, a report by a missionary named Gabriel Sala reported hearing of an "Amachengua"[19] or reincarnation of Inca Juan Santos Atahualpa.[20][21][5] The white figure claimed that the "Sun Father" had sent him with a message that the tribes were to work together. The man to obey on earth and representative of the sun was said to be Carlos Fitzcarrald.[5][22] He threatened that if they did not listen, the rivers would dry up and the game would be chased away.[23][5] Sala described one method of entrapping the natives. This white figure manipulated the natives into gathering at a specific location by using threats or promises.[24][25] Around fifty men employed by Fitzcarrald would greet these natives, and relay that the "Sun Father" wanted to be seen elsewhere. The natives were then coerced into canoes before travelling to the Ucayali, and then either Iquitos or the Manu River: "so that they become slaves in any way, and never see their land again."[24][lower-alpha 4]

"Fitzgerrald intelligently exploited the belief that the Campas have that one day the Son of the Sun will come down from the sky. The rubber worker, to provide himself with pawns, sent emissaries to the nomadic tribes and scattered in the immensity of the jungle, with the slogan of making it known to his ears that in a certain place the Son of the Sun had appeared...They used a surprising cunning to convince the Indians to abandon their freedom; by means of seductive words and gifts, they reduced them and fixed their tents on the banks of the rivers, to have them more at hand as cargo ships for collecting rubber or laborers for the cultivation of the chácaras."

Rubber baron

By 1888, Fitzcarrald was already the richest rubber entrepreneur on the Ucayali River.[28][lower-alpha 5] This year, he visited Iquitos with a large quantity of rubber[25] and many Asháninka servants. In the city, he visited Manuel Cardozo, the owner of a Brazilian firm that exported rubber. There, he fell in love at first sight with Cardozo's stepdaughter, Aurora Velazco who was a widow.[29] They soon married, and Fitzcarrald entered a business partnership with his father-in-law Cardozo to extract rubber in the Ucayali.[25][lower-alpha 6] Carlos already had knowledge and links with the Asháninkas, Humaguacas, Cashivos and other tribes they could exploit to tap rubber. He made fun and jokes out of the rumors that the natives of the Ucayali were savage cannibals: stating someone wise made up the tale.[33] This new coalition dominated trade and the rubber industry in the Atalaya area,[34] which was near the confluence of the Tambo and Urubamba Rivers.[35][36] Fitzcarrald also owned various stations and outposts on the Tambo River.[37] Many of the independent merchants around the Tambo and Ucayali River eventually began working with Fitzcarrald.[38] By 1891 most of the Piro natives on the Urubamba River were indebted to Fitzcarrald.[37][lower-alpha 7]

An important indigenous figure who was a part of Fitzcarrald's network was an Asháninka chief named Venancio Amaringo Campa.[39] Amaringo began working with Carlos Fitzcarrald as early as 1893.[40][lower-alpha 8] Amaringo provided labor for this network by enslaving other native groups, which were then added onto the rubber extracting workforce.[25][43] Slave raids were organized from the Unini River and these raids were primarily focused around the Gran Pajonal area.[44][45][46][lower-alpha 9] Amaringo also organized "punitive expeditions" against other entrepreneurs that Fitzcarrald had disagreements with.[40] Fitzcarrald also had alliances with other Asháninka chiefs that would capture and trade slaves.[48] The rubber firms would "advance" supplies to the Asháninka groups that had agreed to extract rubber, and in this way many natives became indebted to the firms.[49] The Asháninka who did not agree to collect rubber were instead the targets of correrias, or slave raids.[50][51][lower-alpha 10] It was a common practice to kill the indigenous males and enslave the women and children during these raids.[52][53][lower-alpha 11]

Fitzcarrald became established as a rubber baron in the late 19th century.[55][56][lower-alpha 12] Determined to find a way to transport rubber out of the Madre de Dios region, he exploited native workers.[57] Some of the indigenous groups exploited by Fitzcarrald include Asháninka,[58] Piro, and Harakmbut natives.[59][lower-alpha 13] In 1893 he began looking for a route across land which he had heard about from information relayed by natives.[62][63][lower-alpha 14] This was a short and direct route that led from the Urubamba River, to a river which was believed to be the Purus at the time.[62][64][lower-alpha 15] The flotilla of the first expedition was commanded by the Asháninka chief Amaringo, and consisted of around one hundred canoes.[65] In 1894, he forced natives under the threat of death to dismantle and transport a ship over a mountain during the turn-of-the-20th-century rubber boom in the Amazon Basin.[57] Carlos Fitzcarrald became known as the "King of Caucho" rubber.[3][66] Caucho refers to latex extracted from the Castilloa elastica tree.[37][67] Castilloa trees are not suitable for long-term exploitation, and the most effective way of extracting rubber from this tree is to cut it down,[68] and then create deep incisions into the tree with the intention of collecting as much rubber at one time as possible.[69][lower-alpha 16] This incentivized and necessitated constant movement for new sources of rubber trees.[37] The method for extracting latex from Castilloa trees also required a large work force.

Starting in 1894, he explored the Madre de Dios region of BAP Fitzcarrald in Lake Sandoval, Madre de Dios, Peru. He founded the City of Puerto Maldonado and explored the area that is now the Manu Biosphere Reserve. To achieve this, it was necessary to transport his steamship piece by piece over the mountains to the Madre de Dios basin.[57] This ship was the Contamana,[71][72] a boat weighing three tons,[73][64] and it was transported across the isthmus with the effort of around one thousand Piro[71] and Asháninka natives, as well as around 100 non-natives.[72] The portage of the Contamana occurred on Fitzcarrald's second expedition across the isthmus,[62][64] and took two months to complete.[72] The Contamana was bought in Iquitos after Fitzcarrald returned from his first trip across the route.[74] Ernesto de La Combe stated that there were 300 Piros, 500 Asháninka, and 200 nonindigenous men on this second expedition. It took six hundred men to drag the Contamana's hull across the isthmus, logs were placed underneath the boat so it was easier to transport.[74]

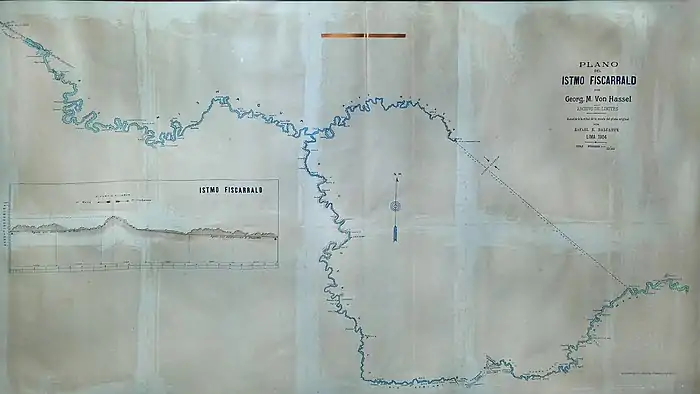

Fitzcarrald is credited with the discovery of a short passage overland between the Mishagua River, a tributary of the Urubamba, and the Manu, a tributary of the Madre de Dios River.[64][75] The former leads into the Ucayali River. The Isthmus of Fitzcarrald was later named after him, as discovery of this route enabled the transportation of rubber from the Madre de Dios region.[76] Rubber was then transferred to ships on the Mishagua, which could reach the Urubamba, the Ucayali River, and thereby down the Amazon to markets and Atlantic ports for export.[57][72] The isthmus was attended to by Piro natives, who took on the task of portage and the shipment of goods across the route.[73] There was also a rubber station at Mishagua, established by Fitzcarrald[77] in 1892.[25][78] It could take around 55 minutes to walk from one end of the isthmus to the other end.[74] Shipibo historian José Roque Maina collected oral testimony from Shipibo natives which "clearly describe their participation in the transport of Fitzcarrald's boat from the Ucayali to the Madre de Dios in 1895."[79]

In an article titled "'Purús Song': Nationalization and Tribalization in Southwestern Amazonia", anthropologist Peter Gow refuted the claims that Fitzcarrald and later his brother Delfín had discovered any portage routes.[lower-alpha 17] Gow emphasized that "[t]hese were standard routes used by Piro people moving between river systems, and are regularly mentioned in the earlier literature... What the 'discoveries' related in the histories actually relate is the increasingly direct articulation of this trading system with the burgeoning rubber-extraction industry in the latter half of the 19th century."[76]

Anthropologist Stefano Varese described a strategy used by Fitzcarrald against the natives, stating: "With a deep knowledge of the mountain, he knew how to use traditional rivalries... The method is simple: Winchesters are given to the Cunibo who must pay in Kampa slaves and then Winchesters are given to the Kampa who must pay in Cunibo [and other] slaves…"[80][lower-alpha 18] Yesica Patiachi, an Indigenous educator stated that to the Harakmbut, Fitzcarrald had "caused the greatest genocide of all time: on one day alone, 3,000 Harakbut were murdered, turning the rivers of our territory red".[82][lower-alpha 19] Hundreds of Toyeri and Araseri natives were massacred in this part of the Madre de Dios because they would not extract rubber for Fitzcarrald or permit his enterprise to travel through their territory.[34][84][lower-alpha 20] An unknown number of their villages were also destroyed.[45][lower-alpha 21] Many Toyeri and Araseri natives fled the area to escape these attacks, however the subsequent migrations led to other conflicts among indigenous groups.[87] The atrocities and abuses perpetrated on behalf of Fitzcarrald were never subjected to a systematic inquiry or investigation during the rubber boom.[88]

Fitzcarrald's expeditions into the Madre de Dios region are considered to be the root of the modern-day divide between the local Yine and Mashco Piro peoples.[lower-alpha 22] The Yine are the descendants of the natives that Fitzcarrald forced to work for him, while the Mashco are the descendants of the natives that fled following Fitzcarrald's arrival.[4] According to Zacarías Valdez Lozano, who was working with Fitzcarrald at the time,[lower-alpha 23] pressure from the rubber barons had essentially evicted the Mashcos from the Manu River.[91][92][lower-alpha 24] Valdez also wrote in his memoirs that after a skirmish occurred on an unfamiliar river, Fitzcarrald named that river Colorado due to the red color of the water.[52]

Most of the Mashco-Piro demographic was slaughtered in 1894 by men working for Fitzcarrald.[94] Euclides da Cunha detailed one massacre in his essay Os caucheros. Fitzcarrald, along with a Piro interpreter attempted to convince a Mashco chief that rather than fighting it would be more advantageous to enter an alliance with Fitzcarrald.[95][lower-alpha 25] The Mashco chief wanted to see the "arrows" that they had brought and was handed a Winchester cartridge. He tried to injure himself with this bullet and after comparing it to an arrow of his own, which he stabbed into his arm, this chief walked away from Fitzcarrald with confidence. After a physical conflict between the two groups lasting half an hour, 100 Mashcos including the chief had been killed.[96] Da Cunha described the small army that accompanied Fitzcarrald as "disparate physiognomies of the tribes he had subjugated".[95][lower-alpha 26] Dominican missionary José Álvarez provided details regarding another conflict between Fitzcarrald and a Mashco tribe, which may have occurred during the same expedition that the incident described by da Cunha happened.

After a beating of drums, Fitzcarrald replied, via an interpreter, that if the Mashco opposed him he would give them a good thrashing, right down to the tiniest baby... the Indians retreated... they tied objects (gifts brought by the rubber barons) to their arrowheads and, drawing their bows, fired them at the encampment... All the tribes rose up to stop Fitzcarrald who, to put an end to the Mashco, prepared a raid with his captains Maldonado, Galdós and Sanchez... In the Comerjali stream they took many prisoners; they executed, after a brief trial, 30 Mashco and destroyed 46 canoes...[lower-alpha 27] Another day, the Mashco killed more than 100 people and so the rubber barons attacked them, by river and by land, with such violence that the Manu was covered in corpses... you couldn’t draw water from the river for all the bodies of Mashco and rubber workers, because it was a war to the death. This took place in 1894.

— José Álvarez[92]

There were also raids against the natives on the other tributaries of the Manu, most notably the Sahuinto, Sotileja, and Fierro.[53][lower-alpha 28] Most of the indigenous men Fitzcarrald's enterprise found during their slave raids along the Manu River were killed.[98][50][53] Some of these slave raids were against Guarayo natives.[99] Fitzcarrald's captain Maldonado, led a campaign in the Sahuinto area, where his group killed many Mashco men there before enslaving their women and children.[100][101] Captain Sanchez destroyed native farms, villages, and canoes on the Sotileja River.[102]

On September 4, 1894, Fitzcarrald arrived at "El Carmen" rubber station, which the Bolivian rubber baron Nicolás Suárez Callaú owned on the Madre de Dios River.[103][104][lower-alpha 29] Fitzcarrald had travelled on the Contamana steamship along with merchandise, which he offered to the Bolivians at lower rates than Suárez could find along the Madeira and Beni Rivers.[105][104] The Isthmus also provided a safer route for Suárez to export the rubber his enterprise collected.[106][104][lower-alpha 30] Suárez decided to invest five hundred thousand Bolivian pesos for the improvement and further development of the new route Fitzcarrald had established.[107][108][lower-alpha 31] Fitzcarrald later travelled further down the Madre de Dios River to the Orton River, where he met Antonio de Vaca Díez, who was a senator for the Bolivian department of Beni and also a rubber baron.[107][lower-alpha 32] Vaca Díez was invited into a newly developing business network, which would create an association of Peruvian, Bolivian, and Brazilian rubber exporters.[104] The Contamana steamship was sold to Fitzcarrald's new Bolivian associates, however, it sank on the same day of its sale, due to unforeseen damages incurred during its travelling.[104] Around three hundred men were distributed at points ranging from twenty to thirty miles between Mishagua and El Carmen to establish new supply stations, which would support the enterprise's operations in the area.[25][111][lower-alpha 33] An engineer named Manuel Balbastro was sent to the isthmus to establish a plan for a railway that would extend from Mishagua to the opposite side of the isthmus on the Manu River.[113][17][lower-alpha 34] Balbastro estimated that this project could cost up to four million Peruvian soles.[17][lower-alpha 35] The project was later abandoned as it was believed to be too expensive.[115] Balbastro was convinced to stay at Mishagua and work for Fitzcarrald's enterprise for a season. He later told Fray Sala about some of the atrocities and abuses he witnessed white caucheros perpetrate against the natives.[116][117][lower-alpha 36]

Transportation on the Madre de Dios for this new partnership would be provided by the steamships La Esperanza, La Shiringa, and La Contamana: while on the Ucayali the steamships Bermúdez,[118][lower-alpha 37] La Unión,[119][lower-alpha 38] Laura, Dorotea,[lower-alpha 39] a tugboat named Bolivar,[lower-alpha 40] Cintra, and Adolfito launches[lower-alpha 41] would facilitate transportation.[118] The steamship Hernán was also chartered by Fitzcarrald in 1895, and transported 50,000 kilos of rubber that year on a voyage back to Iquitos.[123][lower-alpha 42][lower-alpha 43]

In 1896, the Peruvian government granted Fitzcarrald exclusive navigational rights to the Upper Ucayali,[7] Urubamba, Manu, and Madre de Dios River.[101][126][lower-alpha 44] Suárez and Vaca Díez had to negotiate separately with Fitzcarrald so that they could operate on the rivers controlled by him. Suárez offered rubber-bearing lands on the Manu River to Fitzcarrald in exchange for navigational rights.[127][lower-alpha 45] Together, Suárez and Fitzcarrald established a company named Suárez y Fiscarrald.[109] Suárez ships were also permitted to travel through the Urubamba-Ucayali River due to these negotiations.[129] That same year, Vaca Díez made a voyage to London to register The Orton Rubber Co. and he intended to return to Bolivia with several new migrants who would work for him.[129][130][lower-alpha 46] Fitzcarrald and Vaca Díez met again in July 1897 near Mishagua, where they would discuss business.[132][lower-alpha 47]

Fitzcarrald died at age 35, together with his Bolivian business partner Vaca Díez, when their ship Adolfito sank on the Urubamba River in an accident.[134][lower-alpha 48] They were travelling to Mishagua at the head of a convoy, followed by the steamships Laura and Cintra.[136][120][lower-alpha 49] In a letter to her family, Lizzie Hessel, who witnessed the accident, wrote that Fitzcarrald had boarded the Adolfito to convince Vaca Díez to travel on a canoe since Fitzcarrald did not have faith in the new steamship. However, Fitzcarrald was persuaded to stay on this ship with his business partner.[137][138][lower-alpha 50] Lizzie believed that a chain on the Adolfito broke, and afterwards the ship lost control of the current.[137][lower-alpha 51] Albert Perl wrote that after the ship lost control of the current, it was slammed against rocks in the river[133] and then sank.[141] Fitzcarrald's biographer, Reyna, stated that Fitzcarrald was a "renowned swimmer" and had tried to save his friend Vaca Díez, who did not know how to swim.[140] Perl wrote that he witnessed "[b]oth Vaca-Diez and Fizcarrald swung through the windows into the raging flood."[138] Perl was caught in a whirlpool from which he managed to escape, unlike the victims that this accident claimed.[139] Fitzcarrald's body was found days later, and laid to rest in the forest.[137] He was reburied two years later in a cemetery in Iquitos.[142]

Fitzcarrald's wife blamed the group of travelers that were accompanying Vaca Díez for her husband's death, since he had arranged accommodations for this group.[137][lower-alpha 52] Ernesto Reyna blamed Albert Perl for the accident, as he was piloting the Adolfito at the time.[38][144][120] Tony Morrison, who compiled and edited Lizzie Hessel's letters, speculated that the river accident may have been deliberately planned, and he emphasized that "convenient accidents" were a business tactic used by rubber barons.[137][lower-alpha 53] After July 1897, some of the remaining Mashco and Guarayo natives along the Madre de Dios River began attacking canoes and raiding the settlements established by Fitzcarrald's enterprise.[111][146][lower-alpha 54] The Mashcos were able to assume control over the isthmus and burned down rubber stations,[147] killed the mules that provided transportation on the route, and damaged the infrastructure that Fitzcarrald's enterprise had established.[148][lower-alpha 55]

Legacy

Fitzcarrald and Vaca Díez both had a business relationship with Suárez, who would become the primary benefactor of the accident.[150][145] Suárez managed to absorb a substantial portion of Fitzcarrald's fleet,[147][lower-alpha 56] along with many of his Peruvian personnel and soon Suárez became the largest exporter of rubber in Bolivia.[109] Suárez laid claim to the assets owned by Fitzcarrald's enterprise, and began excursions into Peruvian held territory on the Madre de Dios and Ucayali Rivers.[149][147][145] The Orton Rubber Co. which Vaca Díez founded, was entirely absorbed by Suárez's company as well.[152][134] Anthropologist Alberto Chirif believes that a significant factor for the variability of the rubber boom's impact throughout the Amazon is due to the 1897 shipwreck that killed Fitzcarrald and Vaca Díez.[153]

The remainder of Carlos's enterprise came under the direction of his brother Delfin, along with Carlos Scharff and Leopoldo Collazos, two of Fitzcarrald's foremen.[154] The Asháninka chief Venancio Amaringo continued to work with this enterprise even after the death of Delfín Fitzcarrald in 1900.[40][155][lower-alpha 57]The establishment of the portage route between the Urubamba River and the Purus River was disputed between Delfín Fitzcarrald and Leopoldo Collazos.[156] Delfín was killed in an ambush upon returning from his first trip to the Purus River.[157] The Sociedad Geográfica de Lima provided two different accounts regarding this incident, one of these accounts stated that Yaminaguas natives had ambushed Delfín's group.[lower-alpha 58] The other account claimed that "civilized people" disguised as the local natives had carried out the attack. [158] Fitzcarrald's biographer, Ernesto Reyna, stated that natives in the area were harshly punished in retaliation for Delfín's death.[159]

There was suspicion from José Cardoso da Rosa and Edelmira Fitzcarrald towards Leopoldo Collazos and Carlos Scharff regarding the death of Delfín.[157][160][lower-alpha 59] Scharff acquired control over an unknown number of Piro natives that were initially enslaved by the Fitzcarrald family. [161] Around 1903, a dispute over which location Scharff was shipping his rubber to turned into a conflict between Scharff and the Fitzcarrald family. This issue later escalated into a larger border conflict between Peru and Brazil.[162][163][lower-alpha 60] Another brother of Carlos Fitzcarrald, Lorenzo, was murdered in 1905 by bandits on his way back to San Luis. Lorenzo had been managing operations for a rubber enterprise in the years leading up to his death.[164][lower-alpha 61]

Velazco moved to Paris to oversee the upbringing of the children she had with Carlos Fitzcarrald.[157][lower-alpha 62] At least two of their sons, Federico and José, were educated in that city.[165] Velazco also established a hotel in Paris.[166][108] In 1915, Federico and José were controlling a large workforce of Asháninka natives at the Casa Fitzcarrald, located at the confluence of the Urubamba and Tambo Rivers.[35][lower-alpha 63] The Casa Fitzcarrald and two brothers were attacked by an indigenous rebellion that occurred in 1915, and newspapers initially reported that the brothers were killed along with their family. The attackers also took away as many rifles and as much ammunition as they could carry with them.[168] Later reports stated that Federico as well as José survived the attack, and they had organized a retaliatory expedition against the natives consisting of eighty-two men.[169] Casa Fitzcarrald was one of the few rubber exporting enterprises to survive the revolt in 1915 and continue operating.[170] Human trafficking persisted in the Ucayali and Atalaya areas as late as 1988.[88] In 1987, anthropologist Søren Hvalkof discovered that members of the Scharff family, related to Carlos Fitzcarrald's old foreman Carlos Scharff, were still participating in debt bondage.[171] Hvalkof emphasized that the local reputation that Fitzcarrald and Scharff had in the Ucayali area sanctioned the exploitative treatment of natives in that region.[45]

In spite of their crimes, these rubber barons are still national heroes today. In Ucayali and Atalaya they are set up as the models of civilised behaviour. Their culture was refined, they were educated, they knew how to conduct themselves and were forceful. Pianos and velvet furniture. Thus the lines of conduct and rapport with the indigenous population in Atalaya were defined and sanctioned by “public opinion” for many years.

Further reading

Ernesto Reyna published the first biography of Carlos Fitzcarrald in 1942, titled Fitzcarrald, el rey del caucho.[172] Some of this information was disputed by Zacarías Valdez Lozano in 1944, who gave his account of events through a book in Spanish titled El verdadero Fitzcarrald ante la historia.[98] Valdez denied that Fitzcarrald had to use the myth of the "amachengua" in order to dominate the Asháninka natives.[lower-alpha 64] These rumors were first reported by Gabriel Sala in 1897 and included in Reyna's biography, and while Valdez denied this claim, he did not offer an explanation regarding the use of this myth. Anthropologist Michael Fobes Brown suggests that the rumors may have been employed by chiefs like Amaringo, who worked for Fitzcarrald: however he states, that the fact of rather or not those figures were familiar enough with the concept of an "amachengua" to exploit this belief, may never be known.[173] There was another biography on Fitzcarrald published in 2015 by Rafael Otero Mutín, which is regarded as being better documented than Reyna's book.[174]

"Lizzie: A Victorian Lady's Amazon Adventure" is a collection of letters from Elizabeth Mathys Hessel and her husband Fred Hessel to their family in England. Fred Hessel was hired by Antonio de Vaca Díez and travelled with Díez on his return trip from Europe. This book provides insight into the partnership between Carlos Fitzcarrald, Vaca Díez, and Nicolas Suarez, and also an eyewitness account of the Adolfito accident.[135]

Popular culture

- The Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald Province was named after him.

- Puerto Maldonado has a place to view the sunken remains of Fitzcarrald's steamship, the Contamana, which is located in the Madre de Dios River.

- Fitzcarrald's disassembly and transport over a mountainous jungle land bridge, as well as his exploits, inspired director and writer Werner Herzog's film Fitzcarraldo (1982), which symbolizes the extremes generated during the rubber boom and takes Fitzcarrald's symbolic transport of a disassembled ship to an explicit hyperbole by dragging an entire steamboat over a mountain.[57]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Spanish documents, the name Fitzcarrald is also spelt as "Fiscarral" or "Fiscarrald".[1]

- ↑ This title is attributed to Fitzcarrald by his biographer, Ernesto Reyna.

- ↑ Gabriel Sala corroborates that Fitzcarrald's father was an American and his mother was Peruvian.[6]

- ↑ On March 21, 1897, Sala wrote:"All these and a thousand other havocs are caused by the rubber business in Ucayali."[24]

- ↑ He had previously worked along the Pachitea River as well.[15]

- ↑ José Cardozo de Rosa and Carlos Fitzcarrald's brother, Delfín, were working together on the Urubamba River as early as 1892.[30] At the time of Gabriel Sala's journey, Delfín and two of his cousins were staying at the port of Masisea.[31][32]

- ↑ Valdez Lozano noted that some of the Piro natives on the Tambo River were exclusively trading with Fitzcarrald, and had stopped dealing with other white merchants.[37]

- ↑ In 1897 Gabriel Sala documented an encounter with Amaringo, who was leading an expedition with four large canoes and twenty-five armed men.[41] This group arrested a man that was travelling with Sala, and had owed money to Fitzcarrald.[42]

- ↑ Gabriel Sala noted that when he travelled through the Gran Pajonal region, he saw many burned-down houses or abandoned and came across numerous bands of indigenous slave hunters and their "white foremen".[45][47]

- ↑ These methods were also practiced against other native groups, and Fitzcarrald had an alliance with at least four Piro chiefs on the Urubamba River.[38][51]

- ↑ "They would capture women and youths in particular, who formed precious trading objects, whilst adult men were eliminated as they would never form as malleable a workforce as the children, who were more easily and fully assimilated.[54]"

- ↑ During the time his enterprise was active, Fitzcarrald managed rubber operations on the Pachitea, Upper Ucayali, Urubamba, Tambo, Apurimac and the Madre de Dios River.[15]

- ↑ The Piro[60] and Harakmbut, which includes the Mashco,[59] Toyeri and Araseri demographics, all speak Arawakan languages.[61]

- ↑ George Earl Church stated that Fitzcarrald had sent natives up river from the Ucayali to search for a path suitable for portage to the Purus River.[64]

- ↑ Fitzcarrald later discovered that this river was the Madre de Dios rather than the Purus River on his second journey, when he reached a Bolivian rubber station.[64]

- ↑ The India Rubber World described the extraction method this way: "he drains the milk from the entire tree by cutting it down, lopping off the branches, and allowing the sap to collect in holes scooped out in the ground beneath.[70]

- ↑ Delfín is credited with the discovery of a route between the Sepahua and Cujar Rivers.[76]

- ↑ Guillermo Reaño stated that the figure of Carlos Fitzcarrald "represented the epitome of cruelty and indigenous exploitation in the Peruvian forests."[81]

- ↑ Anthropologist Søren Hvalkof also implicates Carlos Fitzcarrald with the genocide of Harakmbut natives.[45] The Harakmbut were also affected by other enterprises durinig the rubber boom, and anthropologist Andrew Gray estimated that between 1894-1914 ninety-five percent of the Harakmbut demographic perished.[83]

- ↑ Toyeri is an extinct ethnic group which was a part of the Harákmbut demographic.[85]

- ↑ "Amongst other things, several hamlets were destroyed with machine guns.[86]"[45]

- ↑ Euclides da Cunha emphasized that Mashco-Piro was one of the groups enslaved by Fitzcarrald.[89]

- ↑ Valdez was Fitzcarrald's "right-hand man" and published his memoirs in 1944.[90] Valdez began working with Fitzcarrald in 1891, when Valdez was 17 years old.[37]

- ↑ Some of the raids described by Valdez were not punitive in nature, but instead they were carried out with the intent of exterminating the native population with the exception of children.[52] Anthropologist Klaus Rummenhoeller referred to Fitzcarrald as "the most bloodthirty of the caucheros of his era."[93]

- ↑ Euclides da Cunha provides the name of the location this incident happened, "Playa Mashcos".[95]

- ↑ Euclides da Cunha provides the name of the location this incident happened, "Playa Mashcos".[95]

- ↑ Ernesto de la Combe corroborated that thirty Mashcos were executed, however his information states that more than ten canoes were destroyed in this incident.[74]

- ↑ Stenfao Varese wrote: "Fitzcarrald, [who], scorning them and killing along the way some who opposed him, has established himself at the center of his domain".[97]

- ↑ El Carmen is located at the confluence of the Sena and Madre de Dios Rivers.[104]

- ↑ Ernesto de La Combe states that around fifty percent of the rubber transported [by natives on canoes] along the Madeira route was lost due to shipwrecks.[104] This was largely due to the rapids locally known as cachuelas, which were significant obstructions for those navigating the Madeira River.[106]

- ↑ According to Frederic Vallve's information, Suárez invested ₤25,000.[109]

- ↑ Vaca Díez was also the cousin of Nicolás Suárez.[110]

- ↑ Gabriel Sala estimated that there was around forty days worth of travelling between Mishagua and Cachuela Esperanza, which is where Nicolas Suárez had his headquarters.[112]

- ↑ Gabriel Sala misspells Manuel's name as Ballarto on page 95 of his book, this is corrected on page 198.[114]

- ↑ According to Ernesto Reyna, this railway was designed to operate a Decauville locomotive.[113]

- ↑ In his 1897 book, Sala did not elaborate on what Balbastro witnessed. Sala wrote "in this matter and in the business of human flesh, there is so much to correct, that it is better not to say anything, until the Supreme Government can operate more quickly on that plethora of scrambles..."[117]

- ↑ This was a 180-ton ship[118] which Suárez purchased in Iquitos.[119] Gabriel Sala travelled on this steamship through territory controlled by Fitzcarrald's enterprise.[6]

- ↑ La Unión was a 60-ton steamship[118] which Suárez ordered from Europe[119]

- ↑ This was a 22-ton ship.[118]

- ↑ This was purchased by Vaca Díez at Orton.[119]

- ↑ The Cintra was a 5-ton ship, while the Adolfito was an 8-ton ship, both of which were purchased by Vaca Díez and brought to Iquitos at the beginning of 1897. He also had another ship named the Sernamby waiting for him in Bolivia.[119] The Adolfito was constructed in London and was specifically designed for navigation on the Amazon rivers.[120] There was a second boat specially constructed in Europe for this enterprise, however the source that refers to this boat does not provide a name.[121][122]

- ↑ Ernesto Reyna stated that "the [Hernán] crossing from Iquitos to Mishagua took 310 hours, and the return in 86 [hours], carrying 50,000 kilos of rubber.[123]

- ↑ The Hernán was chartered by Fitzcarrald from Wesche & Compania in 1894. This was the same company that sold the Laura steamship[124] to Vaca Díez in 1897.[125]

- ↑ This was granted to Fitzcarrald by the Minister of War of Peru at the time, Colonel Juan T. Ibarra.[126][7]

- ↑ Fitzcarrald established rubber stations along the Panahua, Sotileja, Cumerjali, and Cashpajali tributaries on the Manu River.[128]

- ↑ Vaca Díez managed to recruit around five hundred migrants to travel with him across the Atlantic, however only seventeen of them continued the journey with him past Iquitos.[131]

- ↑ According to German Albert Perl, who was navigating the Adolfito, this meeting took place on July 8, 1897.[133]

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel stated that the accident occurred after three days of travelling on the river away from Mishagua.[135]

- ↑ Vaca Díez and his group were travelling to the Orton River, on the other side of the isthmus.[120]

- ↑ Albert Perl described the atmosphere of the ship at the time as festive. The Adolfito had a music box, which played throughout the journey. At the time of the accident, it was playing Martha, of The Market at Richmond.[133][139]

- ↑ Ernesto Reyna also stated that it was the rudder chain that broke.[140]

- ↑ Lizzie also stated that after the death of Fitzcarrald, his wife was physically abusing the natives, and some of them were even chained to her bed at night so that they could not run away. Lizzie referred to Aurora, Fitzcarrald's wife, as a brute. "She beats all her servants about once a week herself."[143]

- ↑ Suárez used the fact that both of his partners had died as justification for Suárez acquiring all of the assets belonging to the partnership.[145]

- ↑ Albert Perl mentioned that after Fitzcarrald's death, natives around Mishagua became rebellious and were attacking the caucheros and their families.[146]

- ↑ After the death of Fitzcarrald and Vaca Diez, Suárez began to primarily export his rubber through the Madeira route again.[149]

- ↑ This included the Shiringa, Esperanza, and Campa steamships. The Campa arrived at the area of operations after the death of Fitzcarrald.[151]

- ↑ The 1915 edition of judge Carlos A. Valcárcel's El proceso del Putumayo y sus secretos inauditos corroborates the fact that Delfín's death occurred three years after his brother Carlos died.[145]

- ↑ Peter Gow's information stated that Delfín was attacked by Amahuaca natives.[157]

- ↑ Edelmira, who was the sister of Carlos and Delfín Fitzcarrald, believed that Collazos had murdered Delfín.[160]

- ↑ A portion of the Fitzcarrald enterprise was acquired by the mother-in-law of Carlos Fitzcarrald. This included large swathes of territory in the Purus and Acre River, which became subject to Brazil due to the actions of Fitzcarrald's mother-in-law.[149][147]

- ↑ Lorenzo was returning to the family home at San Luis with the money he had made while working in the rubber industry. The exact circumstances of his death are unknown, and his body was never found.[164]

- ↑ Together, Aurora and Carlos Fitzcarrald had four children.[137]

- ↑ Federico and José returned to Peru in the early 1910s and assumed operational control over what remained of their father's enterprise. This was after the deaths of their uncles Delfín and Lorenzo.[167]

- ↑ Valdez wrote "[i]n the life of Fitzcarrald, there was nothing of fantasy or legend".[173]

Bibliography

- Gow, Peter (2006). ""Purús Song": Nationalization and Tribalization in Southwestern Amazonia". Tipiti: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America. 4 (1).

- Reyna, Ernesto (1942). Fitzcarrald, el rey del caucho (in Spanish). Taller graf́ico de P. Barrantes C.

- Hessel, Lizzie; Morrison, Tony; Brown, Ann; Rose, Anne (1987). Lizzie: a Victorian lady's Amazon adventure. New York: Parkwest Publications ; London: British Broadcasting Corp.

- Kozikoski Valereto, Deneb (2018). Aporias of Mobility: Amazonian Landscapes between Exploration and Engineering (Thesis). Columbia University Libraries. doi:10.7916/D8QV540Q.

- Huertas Castillo, Beatriz (2004). Indigenous peoples in isolation in the Peruvian Amazon. The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Hecht, Susanna (2013). The Scramble for the Amazon and the Lost Paradise of Euclides Da Cunha. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226322834.

- Manuel Piedrafita Iglesias, Marcelo (2010). Os kaxinawa de felizardo correias trabalho e civilização no alto jurua. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

- Chirif, Alberto; Reaño, Guillermo (2019). Peru: Deforestation in Times of Climate Change. The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- "Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima". Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima. 32 (4). 1917.

- Santos Granero, Fernando; Barclay, Frederica (2002). La frontera domesticada : historia económica y social de Loreto, 1850-2000. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. ISBN 9972424049.

- Marcos de Almeida, Matos (2018). Organização e história dos Manxineru do alto rio Iaco (PhD) (in Portuguese). Federal University of Santa Catarina.

- Santos-Granero, Fernando (2018). Slavery and Utopia The Wars and Dreams of an Amazonian World Transformer. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477316436.

- García Hierro, Pedro; Hvalkof, Søren; Gray, Andrew (1998). Liberation through land rights in the Peruvian Amazon. The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Ferguson, Brian (2000). War in the Tribal Zone Expanding States and Indigenous Warfare. School of American Research Press.

- Eduardo, Fernández; Fobes Brown, Michael (1991). War of Shadows The Struggle for Utopia in the Peruvian Amazon. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520074354.

- Moore, Thomas; Rummenhöller, Klaus; Chavarría, María (2020). Madre de Dios refugio de pueblos originarios. USAID. ISBN 9789972975318.

- Perl, Albert (1904). Durch die Urwälder Südamerikas (in German). De Gruyter, Incorporated. ISBN 9783111111933.

- Junta de Vías Fluviales (1904). El istmo de Fiscarrald (in Spanish). Impr. La Industria.

- Lino e Silva, Moisés; Wardle, Huon (2016). Freedom in Practice Governance, Autonomy and Liberty in the Everyday. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317415497.

- Sala, Gabriel (1897). Apuntes de viaje del R. P. Fr. Gabriel Sala (in Spanish). Impr. La "Industria".

- Roux, Jean-Claude (1994). L'Amazonie Peruvie Ne Un Eldorado dévoré par la forêt 1821-1910 (PDF). Editions L'Harmattan.

- Vallve, Frederic (2010). "The Economics of Rubber and the Habilito System". The impact of the rubber boom on the Bolivian Lowlands (1850-1920) (dissertation). Georgetown University. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- Lawrence, Clayton (1999). Peru and the United States The Condor and the Eagle. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820320243.

- Church, George (1904). "The Acre Territory and the Caoutchouc Region of South-Western Amazonia". Geographical Journal. 23 (5): 596–613. Bibcode:1904GeogJ..23..596C. doi:10.2307/1776006. JSTOR 1776006.

- Fifer, Valerie (1970). "The Empire Builders: A History of the Bolivian Rubber Boom and the Rise of the House of Suarez". Journal of Latin American Studies. 2 (2): 113–146. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00005095. JSTOR 156583. S2CID 145187884. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- Gow, Peter (2001). An Amazonian myth and its history. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924196-5.

- Varese, Stefano (2004). Salt of the Mountain Campa Asháninka History and Resistance in the Peruvian Jungle. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806135120.

- Valcárcel, Carlos (1915). El proceso del Putumayo y sus secretos inauditos. Putumayo: IWGIA. ISBN 9789972941092. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- Curtis Farabee, William (1922). Indian Tribes of Eastern Peru. Read Books. ISBN 9780527012168.

- Dávila Francia, Jesús (2021). "Los dominicos y los pueblos indígenas de Madre de Dios". Arqueologia y Sociedad (in Spanish). 34 (34): 225–239. doi:10.15381/arqueolsoc.2021n34.e20628. S2CID 238844015.

- [175]

References

- ↑ Istmo de Fiscarrald 1904, p. 5-6.

- ↑ Sevillan o, Alfonso Cueva (2004). "Carlos Fermin Fitzcarrald". Diccionario histórico biográfico: peruanos ilustres (in Spanish). A.F.A. Editores Importadores. p. 222.

- 1 2 Lawrence 1999, p. 88.

- 1 2 Anderson, Jon Lee. "An Isolated Tribe Emerges from the Rain Forest". The New Yorker. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Roux 1994, p. 264.

- 1 2 Sala 1897, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 32.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 5.

- ↑ Dávila Francia 2021, p. 233.

- ↑ Serier, Jean-Baptiste (2000). Les barons du caoutchouc. Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement. p. 56. ISBN 9782845860292.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lawrence 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 9.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 7-12.

- 1 2 3 Varese 2004, p. 124.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 13-17.

- 1 2 3 Sala 1897, p. 93.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 18.

- ↑ Ferguson 2000, p. 188.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 19-22.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 130.

- ↑ War of Shadows 1991, p. 62.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 19-23.

- 1 2 3 Sala 1897, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Roux 1994, p. 265.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 22.

- ↑ Paredes Pando, Oscar (2013). Explotación del caucho-shiringa Brasil - Bolivia - Perú: economías extractivo-mercantiles del Alto Acre - Madre de Dios. Editado e impreso en JL Editores. p. 204. ISBN 9786124644702.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 223.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 23.

- ↑ Hecht 2013, p. 394.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 101.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 49-50.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 23-25.

- 1 2 Liberation through land 1998, p. 137.

- 1 2 Santos-Granero 2018, p. 29.

- ↑ Madre de dios 2020, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Freedom in practice 2016, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 War of Shadows 1991, p. 64.

- ↑ War of Shadows 1991, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 Os kaxinawa 2010, p. 54.

- ↑ La frontera domesticada 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 96.

- ↑ Hecht 2013, p. 267.

- ↑ Ferguson 2000, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Liberation through land 1998, p. 138.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 81.

- ↑ Varese 2004, p. 130-131.

- ↑ Ferguson 2000, p. 186-187.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 46.

- 1 2 Santos-Granero 2018, p. 74.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 Valcárcel 1915, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 Huertas Castillo 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Hassel, Georg (1907). Ultimas exploraciones ordenadas por la Junta de Vías Fluviales a los ríos Ucayali, Madre de Dios, Paucartambo y Urubamba. Lima, Perú, Oficina Tipográfica de "La Opinión Nacional," 1907. p. 63.

- ↑ Dolkart, Ronald (1985). "Civilization's Aria: Film as Lore and Opera as Metaphor in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo". Journal of Latin American Lore. 2: 129.

- ↑ Vallve 2010, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dan James Pantone, PhD., "The Myth of Fitzcarraldo", Iquitos News and Travel, 2004-2006

- ↑ Varese 2004, p. 126.

- 1 2 Valcárcel 1915, p. 37.

- ↑ Farabee 1922, p. 53.

- ↑ Farabee 1922, p. 53,77.

- 1 2 3 Roux 1994, p. 266.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Church 1904, p. 602.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 32.

- ↑ Gow 2001, p. 198.

- ↑ Roux 1994, p. 166.

- ↑ Hardenburg, Walter (1912). The Putumayo, the Devil's Paradise; Travels in the Peruvian Amazon Region and an Account of the Atrocities Committed Upon the Indians Therein. London: Fischer Unwin. p. 95.

- ↑ Da Cunha, Euclides. "Os Caucheros". euclidesite (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Dekalb (1890). "The Business of Rubber Gathering in the Amazon Valley". India Rubber World and Electrical Trades Review. 2 (3): 192.

- 1 2 Hecht 2013, p. 393.

- 1 2 3 4 War of Shadows 1991, p. 63.

- 1 2 Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Istmo de Fiscarrald 1904, p. 5.

- ↑ Fifer 1970, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 Gow 2006, p. 284.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Madre de dios 2020, p. 134.

- ↑ Myers, Thomas; Cipolletti, Maria Susana (2002). Artefactos Y Sociedad en Amazonia. Verlag Anton Saurwein. p. 134. ISBN 9783931419639.

- ↑ Varese 2004, p. 106.

- ↑ Deforestation in times of climate change 2019, p. 240.

- ↑ Deforestation in times of climate change 2019, p. 241.

- ↑ Gray, Andrew (1996). The Arakmbut--mythology, Spirituality, and History. Berghahn Books. p. 14. ISBN 9781571818768.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 223-225.

- ↑ Van Linden, An (2019). "Harakmbut". Amazonian Languages, an International Handbook. 2: 2.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 225.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 14,266.

- 1 2 Liberation through land 1998, p. 132.

- ↑ Hecht 2013, p. 482.

- ↑ Huertas Castillo 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Dávila Francia 2021, p. 235.

- 1 2 Huertas Castillo 2004, p. 51-52.

- ↑ Rummenhoeller 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ Scott Wallace (31 January 2012). "Mounting Drama for Uncontacted Tribes". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Da Cunha, Euclides. "Os Caucheros". euclidesite.

- ↑ Hecht 2013, p. 435-436.

- ↑ Varese 2004, p. 127.

- 1 2 Madre de dios 2020, p. 136.

- ↑ Church 1904, p. 604.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 47.

- 1 2 Os kaxinawa 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 48.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Istmo de Fiscarrald 1904, p. 6.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 56.

- 1 2 Vallve 2010, p. 109.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 58.

- 1 2 Roux 1994, p. 271.

- 1 2 3 Vallve 2010, p. 257.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 103.

- 1 2 Istmo de Fiscarrald 1904, p. 7.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 94.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 70.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 95,198.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 116.

- ↑ Roux 1994, p. 153.

- 1 2 Sala 1897, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reyna 1942, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Kozikoski Valereto 2018, p. 157.

- ↑ Sala 1897, p. 86.

- ↑ Roux 1994, p. 270.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 67.

- ↑ La frontera domesticada 2002, p. 110.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 48-49.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 68.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 32,91.

- ↑ Huertas Castillo 2004, p. 50.

- 1 2 Fifer 1970, p. 132.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 12,21.

- ↑ Roux 1994, p. 200.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 Kozikoski Valereto 2018, p. 158.

- 1 2 Fifer 1970, p. 132-133.

- 1 2 Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 66-67.

- ↑ Perl 1904, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 67.

- 1 2 Perl 1904, p. 157.

- 1 2 Perl 1904, p. 158.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 130.

- ↑ Perl 1904, p. 159.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 143.

- ↑ Lizzie Hessel 1987, p. 72-73.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 4 Valcárcel 1915, p. 47.

- 1 2 Perl 1904, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 4 Roux 1994, p. 273.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 Reyna 1942, p. 134.

- ↑ Vallve 2010, p. 109,229-230.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 133.

- ↑ Vallve 2010, p. 230.

- ↑ Oyuela-Bonzani, Isabel. "Exploitive By Design: Warning Signs From the Northwest Amazon". Harvard.Edu. Harvard Graduate School of Design. pp. 52–53. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ↑ Gow 2006, p. 281,284.

- ↑ La frontera domesticada 2002, p. 73.

- ↑ Os kaxinawa 2010, p. 281.

- 1 2 3 4 Gow 2006, p. 281.

- ↑ Sociedad Geográfica de Lima 1917, p. 344.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 141.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 142.

- ↑ Gow 2001, p. 446.

- ↑ Gow 2006, p. 282.

- ↑ Marcos de Almeida 2018, p. 293.

- 1 2 Reyna 1942, p. 157.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 67,156.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 156.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 52.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 30.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 44.

- ↑ Santos-Granero 2018, p. 110.

- ↑ Liberation through land 1998, p. 126.

- ↑ Reyna 1942, p. 1.

- 1 2 War of Shadows 1991, p. 65.

- ↑ Madre de dios 2020, p. 138.

- ↑ Rummenhoeller, Klaus (2003). Los Pueblos Indígenas de Madre de Dios: Historia, etnografía y coyuntura. IWGIA.