Carlos Castillo Armas | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Castillo Armas in 1954 | |

| 28th President of Guatemala | |

| In office 7 July 1954 – 26 July 1957 | |

| Preceded by | Elfego Hernán Monzón Aguirre |

| Succeeded by | Luis González López |

| Personal details | |

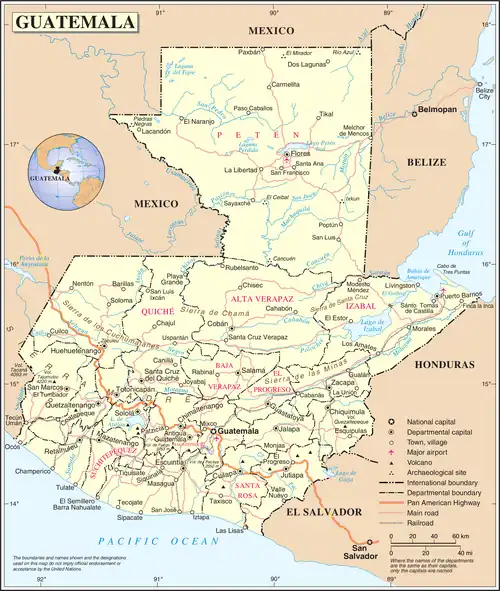

| Born | 4 November 1914 Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa, Guatemala |

| Died | 26 July 1957 (aged 42) Guatemala City, Guatemala |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Political party | National Liberation Movement |

| Spouse | Odilia Palomo Paíz[1] |

| Occupation | Military officer |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Guatemalan Army |

| Years of service | 1933 – 1949[2] |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel[2] |

| Battles/wars | 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état |

| Awards | Mentioned in dispatches (1946)[2] Medal of Military Merit (Mexico) (first class; 1948)[2] |

Carlos Castillo Armas (locally ['kaɾlos kas'tiʝo 'aɾmas]; 4 November 1914 – 26 July 1957) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who was the 28th president of Guatemala, serving from 1954 to 1957 after taking power in a coup d'état. A member of the right-wing National Liberation Movement (MLN) party, his authoritarian government was closely allied with the United States.

Born to a planter, out of wedlock, Castillo Armas was educated at Guatemala's military academy. A protégé of Colonel Francisco Javier Arana, he joined Arana's forces during the 1944 uprising against President Federico Ponce Vaides. This began the Guatemalan Revolution and the introduction of representative democracy to the country. Castillo Armas joined the General Staff and became director of the military academy. Arana and Castillo Armas opposed the newly elected government of Juan José Arévalo; after Arana's failed 1949 coup, Castillo Armas went into exile in Honduras. Seeking support for another revolt, he came to the attention of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1950 he launched a failed assault on Guatemala City, before escaping back to Honduras. Influenced by lobbying by the United Fruit Company and Cold War fears of communism, in 1952 the US government of President Harry Truman authorized Operation PBFortune, a plot to overthrow Arévalo's successor, President Jacobo Árbenz. Castillo Armas was to lead the coup, but the plan was abandoned before being revived in a new form by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953.

In June 1954, Castillo Armas led 480 CIA-trained soldiers into Guatemala, backed by US-supplied aircraft. Despite initial setbacks to the rebel forces, US support for the rebels made the Guatemalan army reluctant to fight, and Árbenz resigned on 27 June. A series of military juntas briefly held power during negotiations that ended with Castillo Armas assuming the presidency on 7 July. Castillo Armas consolidated his power in an October 1954 election, in which he was the only candidate; the MLN, which he led, was the only party allowed to contest the congressional elections. Árbenz's popular agricultural reform was largely rolled back, with land confiscated from small farmers and returned to large landowners. Castillo Armas cracked down on unions and peasant organizations, arresting and killing thousands. He created a National Committee of Defense Against Communism, which investigated over 70,000 people and added 10 percent of the population to a list of suspected communists.

Despite these efforts, Castillo Armas faced significant internal resistance, which was blamed on communist agitation. The government, plagued by corruption and soaring debt, became dependent on aid from the US. In 1957 Castillo Armas was assassinated by a presidential guard with leftist sympathies. He was the first of a series of authoritarian rulers in Guatemala who were close allies of the US. His reversal of the reforms of his predecessors sparked a series of leftist insurgencies in the country after his death, culminating in the Guatemalan Civil War of 1960 to 1996.

Early life and career

Carlos Castillo Armas was born on 4 November 1914, in Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa in the department of Escuintla.[3] He was the son of a landowner, but was born out of wedlock, making him ineligible to inherit the property.[4] In 1936 he graduated from the Guatemalan military academy.[3] His time at the academy overlapped with that of Jacobo Árbenz, who would later become President of Guatemala.[4]

In June 1944, a series of popular protests forced the resignation of dictator Jorge Ubico.[5] Ubico's successor Federico Ponce Vaides pledged to hold free elections, but continued to suppress dissent, leading progressives in the army to plot a coup against him.[6][7] The plot was initially led by Árbenz and Aldana Sandoval; Sandoval persuaded Francisco Javier Arana, the influential commander of the Guardia de Honor, to join the coup in its final stages.[8] On 19 October, Arana and Árbenz launched a coup against Ponce Vaides' government.[9] In the election that followed, Juan José Arévalo was elected president. Castillo Armas was a strong supporter and protégé of Arana, and thus joined the rebels.[3] Speaking of Castillo Armas, Árbenz would later say that he was "modest, brave, sincere" and that he had fought with "great bravery" during the coup.[4]

For seven months, between October 1945 and April 1946, Castillo Armas received training at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he came in contact with American intelligence officers.[10] After serving on the General Staff, he became director of the military academy until early 1949, at which point he was made the military commander at Mazatenango, Suchitepéquez, a remote military garrison.[11] Castillo Armas had eventually risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel.[12][13] He was at Mazatenango when Arana launched his failed coup attempt against Arévalo on 18 July 1949, and was killed: Castillo Armas did not hear of the revolt until four days later.[11] Historians differ on what happened to him at this point. Historian Piero Gleijeses writes that Castillo Armas was expelled from the country following the coup attempt against Arévalo.[14] Nick Cullather and Andrew Fraser state that Castillo Armas was arrested in August 1949,[11] that Árbenz had him imprisoned under doubtful charges until December 1949, and that he was found in Honduras a month later.[11][15]

Operation PBFortune and CIA ties

Following the end of Arévalo's highly popular presidency in 1951, Árbenz was elected president.[16][17] He continued the reforms of Arévalo and also began an ambitious land reform program known as Decree 900. Under it, the uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation[18] and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers.[19] The agrarian reform law angered the United Fruit Company, which at the time dominated the Guatemalan economy. Benefiting from decades of support from the US government, by 1930 the company was already the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala.[20] It was granted further favors by Ubico, including 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land,[21] and an exemption from all taxes.[22]

Feeling threatened by Árbenz's reforms,[23] the company responded with an intensive lobbying campaign directed at members of the United States government.[24] The Cold War had also predisposed the administration of US President Harry Truman to see the Guatemalan government as communist.[25] The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) started to explore the notion of lending support to detractors and opponents of Árbenz. Walter Bedell Smith, the Director of Central Intelligence, ordered J. C. King, the chief of the Western Hemisphere Division, to examine whether dissident Guatemalans could topple the Árbenz government if they had support from the authoritarian governments in Central America.[26]

Castillo Armas had encountered the CIA in January 1950, when a CIA officer learned he was attempting to get weapons from Anastasio Somoza García and Rafael Trujillo, the right-wing authoritarian rulers of Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic, respectively.[11] The CIA officer had described him as "a quiet, soft-spoken officer who [did] not seem to be given to exaggeration".[11] Castillo Armas met with the CIA a few more times before November 1950. Speaking to the CIA, he had stated that he had the support of the Guardia Civil (the Civil Guard), the army garrison at Quezaltenango, as well as the commander of Matamoros, the largest fortress in Guatemala City.[27]

A few days after his last meeting with the CIA, Castillo Armas had led an assault against Matamoros along with a handful of supporters.[11] The attack failed, and Castillo Armas was wounded and arrested.[3][27] A year later, he bribed his way out of prison, and escaped back to Honduras.[27] Castillo Armas's stories of his revolt and escape from prison proved popular among the right-wing exiles in Honduras. Among these people, Castillo Armas claimed to still have support among the army, and began planning another revolt.[27] His reputation was inflated by stories that he had escaped from prison through a tunnel.[4]

The engineer dispatched by the CIA to liaise with Castillo Armas informed the CIA that Castillo Armas had the financial backing of Somoza and Trujillo.[28] Truman thereupon authorized Operation PBFortune.[29] When contacted by the CIA agent dispatched by Smith, Castillo Armas proposed a battle-plan to gain CIA support. This plan involved three forces invading Guatemala from Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador.[28] These invasions were supposed to be supported by internal rebellions.[28] King formulated a plan to provide Castillo Armas with $225,000 as well as weaponry and transportation.[30] Somoza was involved in the scheme; the CIA also contacted Trujillo, and Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the US-supported right-wing dictator of Venezuela, who were both supportive, and agreed to contribute some funding.[29] However, the coup attempt was terminated by Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State, before it could be completed. Accounts of the final termination of the coup attempt vary: some argue that it was due to the US State Department discovering the coup,[29] while others say that it was due to Somoza spreading information about the CIA's role in it, leading to the coup's cover being blown.[31]

Castillo Armas's services were retained by the CIA, who paid him $3,000 a week, which allowed him to maintain a small force. The CIA remained in contact with him, and continued to provide support to the rebels.[32] The money paid to Castillo Armas has been described as a way of making sure that he did not attempt any premature action.[33] Even after the operation had been terminated, the CIA received reports from a Spanish-speaking agent operating under the code name "Seekford" that the Guatemalan rebels were planning assassinations. Castillo Armas made plans to use groups of soldiers in civilian clothing from Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador to kill political and military leaders in Guatemala.[34]

Coup d'état

Planning

In November 1952 Dwight Eisenhower was elected president of the US, promising to take a harder line against communism.[35][36] Senior figures in his administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother and CIA director Allen Dulles, had close ties to the United Fruit Company, making Eisenhower more strongly predisposed than Truman to support Árbenz's overthrow.[32][37] These factors culminated in the Eisenhower administration's decision to authorize "Operation PBSuccess" to overthrow the Guatemalan government in August 1953.[37][38]

The operation had a budget of between five and seven million dollars. It involved a number of CIA agents, and widespread local recruiting.[39] The plans included drawing up lists of people within Árbenz's government to be assassinated if the coup were to be carried out.[40] A team of diplomats who would support PBSuccess was created; the leader of this team was John Peurifoy, who took over as the US ambassador in Guatemala in October 1953.[41]

The CIA considered several candidates to lead the coup. Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the conservative candidate who had lost the 1950 election to Árbenz, held favor with the opposition but was rejected for his role in the Ubico regime, as well as his European appearance, which was unlikely to appeal to the majority mixed-race "Ladinos", or mestizo population.[42] Castillo Armas, in contrast, is described by historian Nick Cullather as a "physically unimposing man with marked mestizo features".[43] Another front-runner was coffee planter Juan Córdova Cerna, who had briefly served in Arévalo's cabinet. The death of his son in an anti-government uprising in 1950 had turned him against the administration. Although his status as a civilian gave him an advantage over Castillo Armas, he was diagnosed with throat cancer in 1954, taking him out of the reckoning.[12][lower-alpha 1]

This led to the selection of Castillo Armas, the former lieutenant of Arana, who had been in exile following the failed coup in 1949.[12][13] Castillo Armas had remained on the CIA payroll since the aborted Operation PBFortune in 1951.[45] Historians have also stated that Castillo Armas was ultimately seen as the most dependable leader from the CIA's perspective.[44] He also had the advantage of having had a clerical education during his exile, and therefore the support of Guatemala's archbishop.[4] In CIA documents, he was referred to by the codename "Calligeris."[46]

Castillo Armas was given enough money to recruit a small force of approximately 150 mercenaries from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of nearby countries. This band was called the "Army of Liberation".[47] The CIA established training camps in Nicaragua and Honduras, and supplied them with weapons as well as several planes flown by American pilots. Prior to the invasion of Guatemala, the US signed military agreements with both of those countries, allowing it to move heavier arms freely. These preparations were only superficially covert: the CIA intended Árbenz to find out about them, as a part of its plan to convince the Guatemalan people that the overthrow of Árbenz was inevitable.[47][48]

Castillo Armas's army was not large enough to defeat the Guatemalan military, even with US-supplied planes. Therefore, the plans for Operation PBSuccess called for a campaign of psychological warfare, which would present Castillo Armas's victory as a fait accompli to the Guatemalan people, and would force Árbenz to resign.[40][49][50] The US propaganda campaign began well before the invasion, with the United States Information Agency writing hundreds of articles on Guatemala based on CIA reports, and distributing tens of thousands of leaflets throughout Latin America. The CIA persuaded the governments that were friendly to it to screen video footage of Guatemala that supported the US version of events.[51] The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station known as the "Voice of Liberation". This station began broadcasting on 1 May 1954, carrying anti-communist messages and telling its listeners to resist the Árbenz government and support the liberating forces of Castillo Armas.[52] The station claimed to be broadcasting from deep within the jungles of the Guatemalan hinterland, a message that many listeners believed. In actuality, the broadcasts were concocted in Miami by Guatemalan exiles, flown to Central America, and broadcast through a mobile transmitter.[52]

Invasion

Castillo Armas's force of 480 men was split into four teams, ranging in size from 60 to 198. On 15 June 1954, these four forces left their bases in Honduras and El Salvador and assembled in various towns just outside the Guatemalan border. The largest force was supposed to attack the Atlantic harbor town of Puerto Barrios, while the others were to attack the smaller towns of Esquipulas, Jutiapa, and Zacapa, the Guatemalan Army's largest frontier post.[53] The invasion plan quickly faced difficulties; the 60-man force was intercepted and jailed by Salvadoran policemen before it got to the border.[53] At 8:20 am on 18 June 1954, Castillo Armas led his invading troops over the border. Ten trained saboteurs preceded the invasion, with the aim of blowing up railways and cutting telegraph lines. At about the same time, Castillo Armas's planes flew over a pro-government rally in the capital.[53] Castillo Armas demanded Árbenz's immediate surrender.[54] The invasion provoked a brief panic in the capital, which quickly decreased as the rebels failed to make any significant headway. Travelling on foot and weighed down by weapons and supplies, Castillo Armas's forces took several days to reach their targets, although their planes blew up a bridge on 19 June.[53]

When the rebels did reach their targets, they experienced further setbacks. The force of 122 men targeting Zacapa was intercepted and decisively beaten by a small garrison of 30 loyalist soldiers, with only 30 rebels escaping death or capture.[55] The force that attacked Puerto Barrios was defeated by policemen and armed dockworkers, with many of the rebels fleeing back to Honduras. In an effort to regain momentum, the rebels attacked the capital with their planes.[55] These attacks caused little material damage, but they had a significant psychological impact, leading many citizens to believe that the invasion force was more powerful than it actually was.[56] The CIA also continued to transmit propaganda from the supposed "Voice of Liberation" station throughout the conflict, broadcasting news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributing to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[57]

Aftermath

Árbenz was initially confident that his army would quickly dispatch the rebel force. The victory of the small Zacapa garrison strengthened his belief.[58] However, the CIA's psychological warfare made the army unwilling to fight Castillo Armas.[59][60] Gleijeses stated that if it were not for US support for the rebellion, the officer corps of the Guatemalan army would have remained loyal to Árbenz because although not uniformly his supporters, they were more wary of Castillo Armas; they had strong nationalist views, and were opposed to foreign interference. As it was, they believed that the US would intervene militarily, leading to a battle they could not win.[59] On 17 June, the army leaders at Zacapa had begun to negotiate with Castillo Armas. They signed a pact, known as the Pacto de Las Tunas, three days later, which placed the army at Zacapa under Castillo Armas in return for a general amnesty.[61] The army returned to its barracks a few days later, "despondent, with a terrible sense of defeat", according to Gleijeses.[61]

Árbenz decided to arm the civilian population to defend the capital; this plan failed, as an insufficient number of people volunteered.[57][62] At this point, Colonel Carlos Enrique Díaz de León, the chief of staff of the Guatemalan army, reneged on his support for the president and began plotting to overthrow Árbenz with the assistance of other senior army officers. They informed Peurifoy of this plan, asking him to stop the hostilities in return for Árbenz's resignation.[63] On 27 June 1954, Árbenz met with Díaz, and informed him that he was resigning.[64] Historian Hugo Jiménez wrote that Castillo Armas's invasion did not pose a significant direct threat to Árbenz; rather, the coup led by Diaz and the Guatemalan army was the critical factor in his overthrow.[65]

Árbenz left office at 8 pm, after recording a resignation speech that was broadcast on the radio an hour later.[63] Immediately afterward, Díaz announced that he would be taking over the presidency in the name of the Guatemalan Revolution, and stated that the Guatemalan army would still fight against Castillo Armas's invasion.[66][67] Peurifoy had not expected Díaz to keep fighting.[64] A couple of days later, Peurifoy informed Díaz that he would have to resign; according to the CIA officer who spoke to Díaz, this was because he was "not convenient for American foreign policy".[61][68] At first, Díaz attempted to placate Peurifoy by forming a junta with Colonel Elfego Monzón and Colonel José Angel Sánchez, and led by himself. Peurifoy continued to insist that he resign, until Díaz was overthrown by a rapid bloodless coup led by Monzón, who, according to Gleijeses, was more pliable.[61][64][67] The other members of Monzón's junta were José Luis Cruz Salazar and Mauricio Dubois.[67][69]

Initially, Monzón was not willing to hand over power to Castillo Armas.[61] The US State Department persuaded Óscar Osorio, the president of El Salvador, to invite Monzón, Castillo Armas, and other significant individuals to participate in peace talks in San Salvador. Osorio agreed to do so, and after Díaz had been deposed, Monzón and Castillo Armas arrived in the Salvadoran capital on 30 June.[61][70][71] Castillo Armas wished to incorporate some of his rebel forces into the Guatemalan military; Monzón, was reluctant to allow this, leading to difficulties in the negotiations.[71][72] Castillo Armas also saw Monzón as having been late to enter the fight against Árbenz.[71] The negotiations nearly broke down on this issue on the very first day, and so Peurifoy, who had remained in Guatemala City to give the impression that the US was not heavily involved, traveled to San Salvador.[61][73] Allen Dulles later said that Peurifoy's role was to "crack some heads together".[73]

Peurifoy was able to force an agreement due to the fact that neither Monzón nor Castillo Armas was in a position to become or remain president without the support of the US. The deal was announced at 4:45 am on 2 July 1954, and under its terms, Castillo Armas and his subordinate, Major Enrique Trinidad Oliva, became members of the junta led by Monzón, although Monzón remained president.[61][70][71] The settlement negotiated by Castillo Armas and Monzón also included a statement that the five-man junta would rule for fifteen days, during which a president would be chosen.[71] Colonels Dubois and Cruz Salazar, Monzón's supporters on the junta, had signed a secret agreement without Monzón's knowledge. On 7 July they resigned in keeping with the terms of the agreement. Monzón, left outnumbered on the junta, also resigned, and on 8 July, Castillo Armas was unanimously elected president of the junta.[61][70] Dubois and Salazar were each paid US $100,000 for cooperating with Castillo Armas.[61] The US promptly recognized the new government on 13 July.[74]

Presidency and assassination

Election

Soon after taking power, Castillo Armas faced a coup from young army cadets, who were unhappy with the army's capitulation. The coup was put down, leaving 29 dead and 91 wounded.[71][75] Elections were held in early October from which all political parties were barred from participating. Castillo Armas was the only candidate; he won the election with 99 percent of the vote, completing his transition into power.[76][77] Castillo Armas became affiliated with a party named the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional (MLN), which remained the ruling party of Guatemala from 1954 to 1957.[78] It was led by Mario Sandoval Alarcón,[78] and was a coalition of municipal politicians, bureaucrats, coffee planters, and members of the military, all of whom were opposed to the reforms of the Guatemalan Revolution.[79] In the congressional elections held under Castillo Armas in late 1955, it was the only party allowed to run.[80]

Authoritarian rule

Prior to the 1954 coup, Castillo Armas had been reluctant to discuss how he would govern the country. He had never articulated any particular philosophy, which had worried his CIA contacts.[43] The closest he came to doing so was the "Plan de Tegucigalpa", a manifesto issued on 23 December 1953, that criticized the "Sovietization of Guatemala".[43] Castillo Armas had expressed sympathy for justicialismo, the philosophy supported by Juan Perón, the President of Argentina.[43]

Upon taking power Castillo Armas, worried that he lacked popular support, attempted to eliminate all opposition. He quickly arrested many thousands of opposition leaders, branding them communists.[81] Detention camps were built to hold the prisoners when the jails exceeded their capacity.[81] Historians have estimated that more than 3,000 people were arrested following the coup, and that approximately 1,000 agricultural workers were killed by Castillo Armas's troops on Finca Jocatán alone, near Tiquisate, which had been a major center of labour organising throughout the decade of the revolution.[82][83] Acting on the advice of Dulles, Castillo Armas also detained a number of citizens trying to flee the country. He also created a National Committee of Defense Against Communism (CDNCC), with sweeping powers of arrest, detention, and deportation.[81] Over the next few years, the committee investigated nearly 70,000 people. Many were imprisoned, executed, or "disappeared", frequently without trial.[81]

In August 1954, the government passed Decree 59, which permitted the security forces to detain anybody on the blacklist of the CDNCC for six months without trial.[84] The eventual list of suspected communists compiled by the CDNCC included one in every ten adults in the country.[84] Attempts were also made to eliminate from government positions people who had gained them under Árbenz.[85] All political parties, labor unions, and peasant organizations were outlawed.[86] In histories of the period, Castillo Armas has been referred to as a dictator.[87]

Castillo Armas's junta drew support from individuals in Guatemala that had previously supported Ubico. José Bernabé Linares, the deeply unpopular head of Ubico's secret police, was named the new head of the security forces.[88] Linares had a reputation for using electric-shock baths and steel skull-caps to torture prisoners.[89] Castillo Armas also removed the right to vote from all illiterate people, who constituted two-thirds of the country's population, and annulled the 1945 constitution, giving himself virtually unbridled power.[81][88] His government launched a concerted campaign against trade unionists, in which some of the most severe violence was directed at workers on the plantations of the United Fruit Company.[90] In 1956 Castillo Armas implemented a new constitution and had himself declared president for four years.[3] His presidency faced opposition from the beginning: agricultural laborers continued to fight Castillo Armas's forces until August 1954, and there were numerous uprisings against him, especially in the areas that had experienced significant agricultural reform.[91]

Opposition to his government grew during Castillo Armas's presidency. On Labor Day in 1956, members of the government were booed off a stage at a labor rally, while officials who had previously been in the Árbenz administration were cheered. The Guatemalan Communist Party began to recover underground, and became prominent in the opposition.[92] Overall, the government had to deal with four serious rebellions, in addition to the coup attempt by the cadets in 1954.[93] On 25 June 1956, government forces opened fire on student protesters, killing six people and wounding a large number.[92] Castillo Armas responded by declaring a "state of siege", and revoked all civil liberties.[92] On the advice of the US ambassador, the protests were portrayed as a communist plot.[92]

Decree 900 reversal

Castillo Armas's government also attempted to reverse the agrarian reform project initiated by Árbenz, and large areas of land were seized from the agrarian laborers who had received them under Árbenz and given to large landowners.[3][85] In only a few isolated instances were peasants able to retain their lands.[85] Castillo Armas's reversal of Árbenz's agrarian reforms led the US embassy to comment that it was a "long step backwards" from the previous policy.[94] Thousands of peasants who attempted to remain on the lands they had received from Árbenz were arrested by the Guatemalan police.[95] Some peasants were arrested under the pretext that they were communists, though very few of them were.[89] Few of these arrested peasants were ever convicted, but landlords used the arrests to evict peasants from their land.[89] The government under Castillo Armas issued two ordinances related to agricultural policy. In theory, these decrees promised to protect the grants of land made by the Árbenz government under Decree 900.[96] The decrees also allowed landowners to petition for the return of land seized "illegally". However, the repressive atmosphere at the time in which the decrees were passed meant that very few peasants could take advantage of them. In total, of the 529,939 manzanas[97][lower-alpha 2] of land expropriated under Decree 900, 368,481 were taken from peasants and returned to landowners.[lower-alpha 3] Ultimately, Castillo Armas did not go as far towards restoring the power and privileges of his upper-class and business constituency as they would have liked.[98] A "liberation tax" that he imposed was not popular among the wealthy.[98]

Economic issues

Castillo Armas's dependence on the officer corps and the mercenaries who had put him in power led to widespread corruption, and the US government was soon subsidizing the Guatemalan government with many millions of dollars.[99] Guatemala quickly came to depend completely on financial support from the Eisenhower administration. Castillo Armas proved unable to attract sufficient business investment, and in September 1954 asked the US for $260 million in aid.[100] Castillo Armas also directed his government to provide support to the CIA operation "PBHistory", an unsuccessful effort to use documents captured after the 1954 coup to sway international opinion in its favor. Despite examining many hundreds of thousands of documents, this operation failed to find any evidence that the Soviet Union was controlling communists within Guatemala.[101] Castillo also found himself too dependent on a coalition of economic interests, including the cotton and sugar industries in Guatemala and real estate, timber, and oil interests in the US, to be able to seriously pursue reforms that he had promised, such as free trade with the US.[78]

By April 1955 the government's foreign exchange reserves had declined from US$42 million at the end of 1954 to just $3.4 million. The regime was thus facing difficulties borrowing money, leading to capital flight. The government also received criticism for the presence of black markets and other signs of approaching bankruptcy.[100] By the end of 1954 the number of unemployed people in the country had risen to 20,000, four times higher than it had been during the latter years of the Árbenz government.[102] In April 1955 the Eisenhower administration approved an aid package of $53 million and began to underwrite the debt of the Guatemalan government.[92] Although officials in the US government complained about Castillo Armas's incompetence and corruption, he also received praise in that country for acting against communists, and his human rights violations generally went unremarked.[103] In 1955, during a corn famine, Castillo Armas gave corn import licenses to some of his old fighters in return for a $25,000 bribe. The imported corn, upon inspection by the United Nations, turned out to be unfit for consumption. When a student newspaper exposed the story, Castillo Armas launched a police crackdown against those criticizing him.[92] Castillo Armas returned some of the privileges that the United Fruit Company had had under Ubico, but the company did not benefit substantially from them; it went into a gradual decline following disastrous experiments with breeding and pesticides, falling demand, and an anti-trust action.[104]

Death and legacy

On 26 July 1957, Castillo Armas was shot dead by a leftist in the presidential palace in Guatemala City.[3] The assassin, Romeo Vásquez Sánchez, was a member of the presidential guard;[93][105] he approached Castillo Armas as he was walking with his wife and shot him twice. Castillo Armas died instantly; Vásquez was reported to have fled to a different room and committed suicide.[93] There is no conclusive information about whether Vásquez was acting alone or whether he was a part of a larger conspiracy.[93] Elections were held following Castillo Armas's death in which the government-aligned Miguel Ortiz Passarelli won a majority. However, supporters of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, who had also been a candidate in the election, rioted, after which the army seized power and annulled the result, and another election was held.[105] Ydígoras Fuentes won this election by a comfortable margin, and soon afterward declared a "state of siege" and seized complete control over the government.[105]

Historian Nick Cullather wrote that by overthrowing Árbenz, the CIA ended up undermining its own initial goal of a stable Guatemalan government.[106] Historian Stephen Streeter stated that while the US achieved certain strategic goals by installing the "malleable" Castillo Armas as president, it did so at the cost of Guatemala's democratic institutions.[107] He further states that, although Castillo Armas probably would have committed the human rights violations that he did even without a US presence, the US State Department had certainly aided and abetted the process.[107] The rolling back of the progressive policies of the previous civilian governments resulted in a series of leftist insurgencies in the countryside beginning in 1960.[108] This triggered the Guatemalan Civil War between the US-backed military government of Guatemala and leftist insurgents, who often boasted a sizable following among the citizenry.[108] The conflict, which lasted between 1960 and 1996, resulted in the deaths of 200,000 civilians.[108][109] Though crimes against civilians were committed by both sides, 93 percent of such atrocities were committed by the US-backed military.[108][110][111][112] These violations included a genocidal scorched-earth campaign against the indigenous Maya population during the 1980s.[108] Historians have attributed the violence of the civil war to the 1954 coup, and the "anti-communist paranoia" that it generated.[113]

Notes and references

Explanatory footnotes

- ↑ Based on documents declassified since 2003, historians have speculated that Córdova Cerna actually had a much larger role in the coup than was previously thought, and that the description of his illness was fictional.[44]

- ↑ One manzana is approximately 1.7 acres (0.69 ha).[97]

- ↑ These figures exclude the land taken from, or returned to, the United Fruit Company. If these figures are included, 603,775 of 765,233 manzanas were returned by the Castillo Armas government.[97]

Citations

- ↑ Way 2012, p. 78.

- 1 2 3 4 "Datos Biográficos del Teniente Coronel de Estado Mayor Carlos Castillo Armas" (PDF). Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (in Spanish). 1950s. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lentz 2014, pp. 342–343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Streeter 2000, p. 25.

- ↑ Forster 2001, p. 86.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 40.

- ↑ Forster 2001, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, p. 50.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 42.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 12–14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cullather 1999, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, pp. 141–143.

- 1 2 Gilderhus, LaFevor & LaRosa 2017, p. 137.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 59–69.

- ↑ Fraser 2006, p. 491.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 11.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 82–84.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 11–13, 67–71.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 12.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 75–82.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 72–77.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 82–100.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 1999, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 3 Cullather 1999, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Gleijeses 1992, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 31.

- 1 2 Cullather 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ De La Pedraja 2013, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Hanhimäki & Westad 2004, pp. 456–457.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, p. 234.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 122–127.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 138–143.

- 1 2 Kornbluh 1997.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 45.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 1999, p. 50.

- 1 2 Fraser 2006, p. 496.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 28–35.

- ↑ State Department 2004.

- 1 2 Immerman 1982, pp. 162–165.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 114–116.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 165.

- ↑ Jiménez 1985, pp. 152–154.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 166.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 74–77.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullather 2006, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, p. 161.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 90–93.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 Cullather 2006, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 326–329.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1992, pp. 330–335.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gleijeses 1992, pp. 354–357.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 342–345.

- 1 2 Gleijeses 1992, pp. 345–349.

- 1 2 3 Immerman 1982, p. 174.

- ↑ Jiménez 1985, p. 155.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 102–105.

- 1 2 3 Castañeda 2005, p. 92.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 206.

- ↑ McCleary 1999, p. 237.

- 1 2 3 Lentz 2014, pp. 343–343.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Life 1954.

- ↑ Handy 1994, p. 193.

- 1 2 Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 212–215.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 216.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 42.

- ↑ Immerman 1982, pp. 173–178.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 224–225.

- 1 2 3 Grandin 2004, p. 86.

- ↑ Booth 2014, p. 175.

- ↑ Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 248.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Immerman 1982, pp. 198–201.

- ↑ Grandin 2000, p. 321.

- ↑ Forster, Cindy (2003). Banana Wars. Degruyter. p. 191. ISBN 0822331969.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 Forster 2001, pp. 202–210.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Fraser 2006, p. 504.

- 1 2 Cullather 1999, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Streeter 2000, p. 40.

- ↑ Forster 2001, p. 202.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cullather 1999, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 4 Streeter 2000, p. 54.

- ↑ Gleijeses 1992, p. 382.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 109.

- ↑ Handy 1994, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 Handy 1994, p. 197.

- 1 2 Handy 1994, p. 194.

- ↑ Cullather 2006, pp. 114–115.

- 1 2 Cullather 1999, p. 114.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 107.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 53.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, pp. 30–45.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 Cullather 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Cullather 1999, p. 117.

- 1 2 Streeter 2000, pp. 50–58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McAllister 2010, pp. 276–277.

- ↑ Streeter 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ Mikaberidze 2013, p. 216.

- ↑ Harbury 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Horvitz & Catherwood 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Figueroa Ibarra 1990, p. 113.

General and cited references

- Booth, John A.; Wade, Christine J.; Walker, Thomas (2014). Understanding Central America: Global Forces, Rebellion, and Change. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4959-6.

- Castañeda, Manolo E. Vela (2005). "Guatemala 1954: Las ideas de la contrarrevolución" [Guatemala 1954: the Ideas of a Counterrevolution]. Foro Internacional (in Spanish). 45 (1): 89–114. JSTOR 27738691. OCLC 820336083.

- Cullather, Nicholas (2006). Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala 1952–54. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5468-2.

- Cullather, Nicholas (1999). Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala 1952–54. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3311-3.

- De La Pedraja, René (2013). Wars of Latin America, 1948–1982: The Rise of the Guerrillas. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7015-0.

- Figueroa Ibarra, Carlos (January–February 1990). "El recurso del miedo: estado y el terror en Guatemala" [The Appeal of Fear: State and Terror in Guatemala]. Nueva Sociedad (in Spanish) (105): 108–117. ISBN 9789929552395.

- Forster, Cindy (2001). The Time of Freedom: Campesino Workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0.

- Fraser, Andrew (August 2006). "Architecture of a Broken Dream: The CIA and Guatemala, 1952–54". Intelligence and National Security. 20 (3): 486–508. doi:10.1080/02684520500269010. S2CID 154550395.

- Gilderhus, Mark T.; LaFevor, David C.; LaRosa, Michael J. (2017). The Third Century: U.S.–Latin American Relations since 1889. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5717-7.

- Gleijeses, Piero (1992). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8.

- Grandin, Greg (2000). The Blood of Guatemala: A History of Race and Nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9.

- Grandin, Greg (2004). The Last Colonial Massacre. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30572-4.

- Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the Countryside: Rural Conflict and Agrarian Reform in Guatemala, 1944–1954. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4438-0.

- Hanhimäki, Jussi; Westad, Odd Arne (2004). The Cold War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927280-8.

- Harbury, Jennifer (2005). Truth, Torture, and the American Way: The History and Consequences of U.S. Involvement in Torture. Beacon Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8070-0307-7.

- Horvitz, Leslie Alan; Catherwood, Christopher (2006). Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide. Facts On File Inc. ISBN 978-1-4381-1029-5.

- Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2.

- Jiménez, Hugo Murillo (1985). "La intervención Norteamericana en Guatemala en 1954: Dos interpretaciones recientes" [North American Intervention in Guatemala in 1954: Two Recent Interpretations]. Anuario de Estudios Centroamerica (in Spanish). 11 (2): 149–155. ISSN 0377-7316.

- Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. (23 May 1997) [1994], "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 4, National Security Archive

- Lentz, Harris M. (2014). Heads of States and Governments Since 1945. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-26490-2.

- "The End Of a Twelve Day Civil War". Life. Vol. 37, no. 2. 12 June 1954. pp. 21–22. ISSN 0024-3019.

- McAllister, Carlota (2010). "A Headlong Rush into the Future". In Grandin, Greg; Joseph, Gilbert (eds.). A Century of Revolution. Duke University Press. pp. 276–309. ISBN 978-0-8223-9285-9.

- McCleary, Rachel M. (1999). Dictating Democracy: Guatemala and the End of Violent Revolution. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1726-6.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2013). Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59884-926-4.

- Office of the Historian, US State Department (2003). "Foreign Relations, Guatemala, 1952–1954; Documents 1–31". US State Department.

- Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0.

- Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the counterrevolution: the United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5.

- Way, J. T. (2012). The Mayan in the Mall: Globalization, Development, and the Making of Modern Guatemala. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5131-3.

Further reading

- Koeppel, Dan (2008). Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. Hudson Street Press. ISBN 978-1-101-21391-9.

- Krehm, William (1999). Democracies and Tyrannies of the Caribbean in 1940s. COMER Publications. ISBN 978-1-896266-81-7.

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable revolutions: The United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.

- Loveman, Brian; Davies, Thomas M. (1997). The Politics of Antipolitics: The Military in Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2611-6.

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (2009). La Patria del Criollo: An Interpretation of Colonial Guatemala (in Spanish). Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9206-4.

- Paterson, Thomas G.; et al. (2009). American Foreign Relations: A History, Volume 2: Since 1895. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8223-9206-4.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (1988). Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4204-1.

- Sabino, Carlos (2007). Guatemala, la Historia Silenciada (1944–1989) [Guatemala, a Silenced History] (in Spanish). Vol. 1: Revolución y Liberación. Guatemala: Fondo Nacional para la Cultura Económica. ISBN 978-99922-48-52-2.

External links

Media related to Carlos Castillo Armas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carlos Castillo Armas at Wikimedia Commons