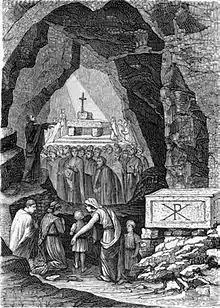

The Catacomb(s) of Callixtus (also known as the Cemetery of Callixtus) is one of the Catacombs of Rome on the Appian Way, most notable for containing the Crypt of the Popes (Italian: Cappella dei Papi), which once contained the tombs of several popes from the 2nd to 4th centuries.[1][2]

History

The Catacomb is believed to have been created by future Pope Callixtus I, then a deacon of Rome, under the direction of Pope Zephyrinus, enlarging pre-existing early Christian hypogea. Callixtus himself was entombed in the Catacomb of Calepodius on the Aurelian Way. The crypt fell into disuse and decay as the relics it contained were translated from the catacombs to the various churches of Rome; the final wave of translations from the crypt occurred under Pope Sergius II in the 9th century, primarily to San Silvestro in Capite, which unlike the Catacomb was within the Aurelian Walls.[1] The Catacomb and Crypt were rediscovered in 1854 by the pioneering Italian archaeologist Giovanni Battista de Rossi.[1]

Description

The catacomb forms part of an ancient funerary complex, the Complesso Callistiano, that occupies thirty hectares. The boundaries of this are taken as being the Via Appia Antica, the Via Ardeatina and the Vicolo delle Sette Chiese. The area of the catacomb proper is about fifteen hectares, and it goes down for five levels.[3] A rough estimate puts the length of passageways at about twenty kilometres, and the occupancy at about half a million bodies.[4]

This catacomb's most ancient parts are the crypt of Lucina, the region of the Popes and the region of Saint Cecilia, where some of the most sacred memories of the place are preserved (including the crypt of the Popes, the crypt of Saint Cecilia, and the crypt of the Sacraments); the other regions are named the region of Saint Gaius and the region of Saint Eusebius (end of the 3rd century), West region (built in the first half of the 4th century) and the Liberian region (second half of the 4th century), all showing grandiose underground architecture. A modern staircase, on the site of an ancient one, was built by Pope Damasus I, giving access to the region of the Popes, in which is to be found the Crypt of the Popes, where nine pontiffs and, perhaps, eight representatives of the ecclesiastical hierarchy had been buried – along its walls are the original Greek inscriptions for the pontiffs Pontian, Anterus, Fabian, Lucius I and Eutychian. In the far wall Pope Sixtus II was also buried, after he was killed during the persecution of Valerian; in front of his tomb Pope Damasus had carved an inscription in poetic metre in characters thought up by the calligrapher Furius Dionysius Filocalus.

In the adjoining crypt is the grave of Saint Cecilia, whose relics were removed by Pope Paschal I in 821: the early 9th-century frescoes on the walls represent Saint Cecilia praying, the bust of the Redeemer and Pope Urban I. A short distance away, an arcade dating to the end of the 2nd century gives access to the cubicula of the sacraments, with their frescoes from the first half of the 3rd century hinting at baptism, the Eucharist and the resurrection of the flesh; in the region of Saint Militiades next door, a child's sarcophagus has a front sculpted with biblical episodes. In the region of Saints Gaius and Eusebius are some crypts set apart, opposite each other, with the tombs of Pope Gaius (with an inscription) and Pope Eusebius, who died in Sicily where he had been exiled by Maxentius and whose body was translated to Rome during the pontificate of Militiades; on a marble copy of the end of the 4th century (of which fragments may be seen on the opposite wall) may be read of an inscription by Damasus which highlights Eusebius' role in the resolution of schism in the early church, particularly as it related to the acceptance of apostates.

Along "passage O" north of the Crypt of the Popes are, in succession, the crypt of the martyrs Calogerus and Parthenius and the double cubiculum of Severus, which contains a rhythmic inscription (dated to no later than 304) in which a bishop of Rome (at that time Marcellinus) is first called pope and first openly professes belief in the final resurrection. In a region further from there, the so-called "Crypt of Lucina", is the burial of Pope Cornelius, whose tomb still has its original inscription giving him the title of martyr and, on its sides, splendid paintings with figures in 7th and 8th century Byzantine style representing popes Sixtus II and Cornelius and the African bishops Cyprian and Ottatus. In a nearby cubiculum are some of the most ancient burials, after AD 175, with Roman frescoes of (on the ceiling) the Good Shepherd and orantes and (on the far wall) two fish with a basket of loaves behind it, a symbol of the Eucharist.

Papal tombs

At its peak, the 15-hectare (37-acre) site would have held the remains of 16 popes and 50 martyrs. Nine of those popes were buried in the Crypt of the Popes itself, to which Pope Damasus I built a staircase in the 4th century. Among the discovered Greek language inscriptions are those associated with: Pope Pontian, Pope Anterus, Pope Fabian, Pope Lucius I, and Pope Eutychian. A more lengthy inscription to Pope Sixtus II by Furius Dionisius Filocalus has also been discovered.

Outside the Crypt of the Popes, the region of Saints Gaius and Eusebius is so named for the facing tombs of Pope Gaius ("Caius") and Pope Eusebius (translated from Sicily). In another region, there is a tomb attributed to Pope Cornelius, bearing the inscription "CORNELIVS MARTYR", also attributed to Filocalus.[5]

A plaque placed by Pope Sixtus III (c. 440) lists the following popes: Sixtus II, Dionysius, Cornelius, Felix, Pontianus, Fabianus, Gaius, Eusebius, Melchiades, Stephen, Urban I, Lucius, and Anterus, a list not including any 2nd century tombs.[6] The Crypt of the Popes quickly filled up in the 4th century, causing other popes to be buried in related catacombs, such as the Catacomb of Priscilla, the Catacomb of Balbina (only Pope Mark), the Catacomb of Calepodius (only Pope Callixtus I and Pope Julius I), the Catacomb of Pontian (only Pope Anastasius I and Pope Innocent I, father and son), and the Catacomb of Felicitas (only Pope Boniface I).[7]

2nd century

| Pontificate | Portrait | Common English name | Pre-Callixtus translations | Location within Callixtus | Post-Callixtus translations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 155–166 |  |

Anicetus Saint Anicetus |

Vatican Hill (some sources say he was originally buried in the Catacomb of Callixtus) | Unknown | Altemps Palace (Piazza Navona) | Sarcophagus which may have once contained remains is extant in the Altemps Palace[8][9] |

| c. 166–174/175 |  |

Soter Saint Soter |

None | Unknown | San Silvestro in Capite San Sisto Vecchio Toledo, Spain San Martino ai Monti |

Possibly never buried in Catacomb of Callixtus and confused with a martyr buried in 304[8][10] |

| 199–217 |  |

Zephyrinus Saint Zephyrin |

Private cemetery ("in cymiterio suo")[11] | Not in the Crypt of the Popes | San Silvestro in Capite | First pope buried in the Catacomb, which he ordered Callixtus to organize[10] |

3rd century

| Pontificate | Portrait | Common English name | Pre-Callixtus translations | Location within Callixtus | Post-Callixtus translations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 222/223–230 |  |

Urban I Saint Urban |

None | Unknown (see notes) | None known | Not to be confused with a non-Roman bishop Urban buried in the catacomb of Praetextatus; slab in Crypt of the Popes bears the Greek words: OYPBANOC E[ΠΙCΚΟΠΟC] ("Urban, Bishop"), but identification is not certain[12] |

| 21 July 230 – 28 September 235 |  |

Pontian Saint Pontian |

Sardinia | Crypt of the Popes | None known | Translated from Sardinia (the "Isle of Death") by Pope Fabian in 237, buried in the papal crypt on November 12; two extant engravings: ΠONTIANOC EΠI[CΚΟΠΟC] M[ΑΡΤΥ]Ρ ("Pontianus Bi[shop] M[arty]r"); and ΕΝθΕΩΝ [ΑΓΙΩΝ ΕΠΙCΚΟΠΩΝ] ΠΟΝΤΙΑΝΕ ΖΗϹΗϹ ("Mayest thou live, Pontianus, in God with all")[12][13] |

| 21 November 235 – 3 January 236 |  |

Anterus Saint Anterus |

None | Crypt of the Popes | San Silvestro in Capite | Possibly the first pope in the Crypt of the Popes; inscription reads ΑΝΘΕΡΩϹ EΠI[CΚΟΠΟC] ("Anterus, Bishop") and is broken such that it could have once mentioned him as a martyr[13] |

| 10 January 236 – 20 January 250 |  |

Fabian Saint Fabian |

None | Crypt of the Popes | San Martino ai Monti Old St. Peter's Basilica San Sebastiano fuori le mura |

Greek inscription from the Catacomb of Callixtus is extant; translated to San Martino by Sergius II (Liber Pontificalis) or combined with Sixtus II in Old St. Peter's (Petrus Mallius); sarcophagus inscribed with ΦΑΒΙΑΝΟϹ ΕΠΙ[CΚΟΠΟC] Μ[ΑΡΤΥ]Ρ ("Phabianos Bi[shop] M[arty]r") in San Sebastiano fuori le mura[13] |

| 25 June 253 – 5 March 254 |  |

Lucius I Saint Lucius |

None | Crypt of the Popes | Santa Cecilia in Trastevere San Silvestro in Capite Santa Prassede |

Extant inscription reads "Lucius, Bishop" (Greek: ΛΟΥΚΙϹ) sarcophagus that once held remains is extant in Santa Cecilia in Trastevere[9][14] |

| 30/31 August 257 – 6 August 258 | Sixtus II Saint Sixtus II |

None | Crypt of the Popes | Old St. Peter's Basilica San Sisto Vecchio |

Translated from the Catacomb of Callixtus to Old Saint Peter's by Paschal I; translated from Old Saint Peter's to San Sisto Vecchio by Leo IV; lengthy epitaph discovered in the Catacomb of Callixtus[14] | |

| 22 July 259 – 26 December 268 |  |

Dionysius Saint Dionysius |

None | Crypt of the Popes | San Silvestre in Capite | Alleged relics of Popes Sylvester I, Stephen I, and Dionysius were exhumed and enshrined beneath the high altar of San Silvestro in Capite in 1601; no archaeological evidence in the Catacomb of Callixtus[15] |

| 5 January 269 – 30 December 274 |  |

Felix I Saint Felix |

None | Crypt of the Popes | None known | According to legend buried in the "Cemetery of the Two Felixes", which has never been located[15] |

| 4 January 275 – 7 December 283 |  |

Eutychian Saint Eutychian |

None | Crypt of the Popes | Abbey of Luni (Sarzana) Sarzana Cathedral |

Last pope buried in the Crypt of the Popes; inscription reads: EYTYXIANOC EΠΙC[KOΠOC] ("Eutychian, Bishop")[15] |

| 17 December 283 – 22 April 296 |  |

Caius Saint Caius |

None | Crypt of St. Eusebius | San Silvestro in Capite Church built over his original house Sant'Andrea della Valle (Barberini chapel) |

Inscription reads: Γ[AIO]Y EΠI[ϹΚΟΠΟΥ] / ΚΑ[TA]Θ[ECIC] / [ΠΡΟ I] ΚΑΛ MAIΩ[N] ("The deposition of Caius, Bishop, the 22nd day of April")[15] |

4th century

| Pontificate | Portrait | Common English name | Pre-Callixtus translations | Location within Callixtus | Post-Callixtus translations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 309 – c. 310 |  |

Eusebius Saint Eusebius |

Sicily | Crypt of St. Eusebius | None known | Inscription and lengthy epitaph extant[16][17] |

| 2 July 311 – 11 January 314 |  |

Miltiades Melchiades Saint Miltiades |

None | Unknown | San Silvestre in Capite | Only pope entombed in the Catacomb of Callixtus during the "long peace"; buried in a large sarcophagus with a roof-shaped cover[17] |

| 1 October 366 – 11 December 384 |  |

Damasus I Saint Damasus |

None | Unknown | Old St. Peter's Basilica San Lorenzo in Damaso |

Buried with his mother, Laurentia, and sister, Irene; sarcophagus inscription extant; head allegedly in a reliquary donated by Clement VIII to St. Peter's[18] |

In popular culture

In the novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by Lew Wallace, Judah Ben-Hur, along with his wife Esther and Malluch, decide to build the catacomb.

In the novel The Marble Faun by Nathaniel Hawthorne, chapters 3 and 4 describe a visit to the catacomb. As it was published in 1860, this is an early literary description of the recently discovered site.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Reardon 2004, p. 291.

- ↑ Carragáin, Éamonn Ó; Neuman de Vegvar, Carol L., eds. (2007). Roma felix: formation and reflections of medieval Rome. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7546-6096-5. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- ↑ Meera Lester: "Sacred Travels" 2011, p. 244

- ↑ Matilda Webb: "The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome" 2002

- ↑ Saghy, Marianne (2000). "Scinditur in partes populus: Pope Damasus and the Martyrs of Rome". Early Medieval Europe. 9 (3): 273. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00070. S2CID 161067498.

- ↑ Reardon 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Reardon 2004, p. 11.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 25.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 270.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ Johnson, Mark Joseph (1997). "Pagan-Christian Burial Practices of the Fourth Century: Shared Tombs?". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 5 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1353/earl.1997.0029. S2CID 170377420.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Reardon 2004, p. 28.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 Reardon 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Reardon 2004, p. 32.

- 1 2 Reardon 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ Reardon 2004, p. 37.

References

- Reardon, Wendy J. (2004). The Deaths of the Popes: Comprehensive Accounts, Including Funerals, Burial Places and Epitaphs. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 320. ISBN 0-7864-1527-4.