| Cervical cerclage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | obstetrics and gynaecology |

| ICD-9-CM | 67.5 |

| MeSH | D023802 |

| eMedicine | 1848163 |

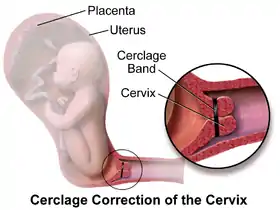

Cervical cerclage, also known as a cervical stitch, is a treatment for cervical weakness, when the cervix starts to shorten and open too early during a pregnancy causing either a late miscarriage or preterm birth. In women with a prior spontaneous preterm birth and who are pregnant with one baby, and have shortening of the cervical length less than 25 mm, a cerclage prevents a preterm birth and reduces death and illness in the baby.[1]

The treatment consists of a strong suture sewn into and around the cervix early in the pregnancy, usually between weeks 12 to 14, and then removed towards the end of the pregnancy when the greatest risk of miscarriage has passed. The procedure is performed under local anaesthesia, usually by way of a spinal block. It is typically performed on an outpatient basis by an obstetrician-gynecologist. Usually the treatment is done in the first or second trimester of pregnancy, for a woman who has had one or more late miscarriages in the past.[2] The word "cerclage" means encircling, hooping or banding in French.[3]

The success rate for cervical cerclage is approximately 80–90% for elective cerclages, and 40–60% for emergency cerclages. A cerclage is considered successful if labor and delivery is delayed to at least 37 weeks (full term). After the cerclage has been placed, the patient will be observed for at least several hours (sometimes overnight) to ensure that she does not go into premature labor. The patient will then be allowed to return home, but will be instructed to remain in bed or avoid physical activity (including sexual intercourse) for two to three days, or up to two weeks. Follow-up appointments will usually take place so that her doctor can monitor the cervix and stitch and watch for signs of premature labor.

For women who are pregnant with one baby (a singleton pregnancy) and at risk for a preterm birth, when cerclage is compared with no treatment, there is a reduction in preterm birth and there may be a reduction in the number of babies who die (perinatal mortality)[2] There is no evidence that cerclage is effective in a multiple gestation pregnancy for preventing preterm births and reducing perinatal deaths or neonatal morbidity.[4] Various studies have been undertaken to investigate whether cervical cerclage is more effective when combined with other treatments, such as antibiotics or vaginal pessary, but the evidence remains uncertain.[5]

Types

There are three types of cerclage:[6]

- A McDonald cerclage, described in 1957, is the most common, and is essentially a pursestring stitch used to cinch the cervix shut; the cervix stitching involves a band of suture at the upper part of the cervix while the lower part has already started to efface.[2] This cerclage is usually placed between 16 weeks and 18 weeks of pregnancy. The stitch is generally removed around the 37th week of gestation or earlier if needed.[7] This procedure was developed by the Australian gynecologist and obstetrician, I.A. McDonald.[8]

- A Shirodkar cerclage is very similar, but the sutures pass through the walls of the cervix so they're not exposed.[2] This type of cerclage is less common and technically more difficult than a McDonald, and is thought (though not proven) to reduce the risk of infection. The Shirodkar procedure sometimes involves a permanent stitch around the cervix which will not be removed and therefore a Caesarean section will be necessary to deliver the baby. The Shirodkar technique was first described by V. N. Shirodkar in Bombay in 1955.[9] In 1963, Shirodkar traveled to NYC to perform the procedure at the New York Hospital of Special Surgery; the procedure was successful, and the baby lived to adulthood.

- An abdominal cerclage, the least common type, is permanent and involves placing a band at the very top and outside of the cervix, inside the abdomen. This is usually only done if the cervix is too short to attempt a standard cerclage, or if a vaginal cerclage has failed or is not possible. However, a few doctors (namely Arthur Haney at the University of Chicago and George Davis at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) are pushing for the transabdominal cerclage (TAC) to replace vaginal cerclages, due to perceived better outcomes and more pregnancies carried to term. A c-section is required for women giving birth with a TAC. A transabdominal cerclage can also be placed pre-pregnancy if a patient has been diagnosed with an incompetent cervix.[2]

Risks

While cerclage is generally a safe procedure, there are a number of potential complications that may arise during or after surgery. These include:

- risks associated with regional or general anesthesia

- premature labor

- premature rupture of membranes

- infection of the cervix

- infection of the amniotic sac (chorioamnionitis)

- cervical rupture (may occur if the stitch is not removed before onset of labor)

- uterine rupture (may occur if the stitch is not removed before onset of labor)[10]

- injury to the cervix or bladder

- bleeding

- Cervical Dystocia with failure to dilate requiring Cesarean Section

- displacement of the cervix

Alternatives

The Arabin Pessary is a silicone device that has been suggested to prevent spontaneous preterm birth without the need for surgery.[11] The leading hypotheses for its mechanisms were that it could help keep the cervix closed similarly to the cerclage, as well as change the inclination of the cervical canal so that the pregnancy weight is not directly above the internal os. However, large randomized clinical trials in singleton[12] and twin pregnancies[13] found that the cervical pessary did not result in a lower rate of spontaneous early preterm birth. Therefore, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommendation is that placement of cervical pessary in pregnancy to decrease preterm birth, should be used only in the context of a clinical trial or research protocol.[14]

References

- ↑ Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski JM, Rust OA, Owen J (March 2011). "Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: a meta-analysis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 117 (3): 663–671. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31820ca847. PMID 21446209. S2CID 7509348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N (June 2017). "Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (6): CD008991. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008991.pub3. PMC 6481522. PMID 28586127.

- ↑ Stedman T (1987). Webster's New World/Stedman's Concise Medical Dictionary (1 ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. p. 130. ISBN 0139481427.

- ↑ Rafael TJ, Berghella V, Alfirevic Z (September 2014). "Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in multiple pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD009166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009166.pub2. PMC 10629495. PMID 25208049.

- ↑ Eleje GU, Eke AC, Ikechebelu JI, Ezebialu IU, Okam PC, Ilika CP (September 2020). "Cervical stitch (cerclage) in combination with other treatments for preventing spontaneous preterm birth in singleton pregnancies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (9): CD012871. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012871.pub2. PMC 8094629. PMID 32970845.

- ↑ Paula J. Adams Hillard, ed. (1 May 2008). Five-minute obstetrics and gynecology consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 482–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6942-6. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ↑ "Cervical Cerclage". American Pregnancy Association. 26 April 2012. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- ↑ Mcdonald IA (June 1957). "Suture of the cervix for inevitable miscarriage". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. 64 (3): 346–350. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1957.tb02650.x. PMID 13449654. S2CID 73159712.

- ↑ Goulding E, Lim B (August 2014). "McDonald transvaginal cervical cerclage since 1957: from its roots in Australia into worldwide contemporary practice". BJOG. 121 (9): 1107. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12874. PMID 25047486. S2CID 21004646.

- ↑ Nashar, S., Dimitrov, A., Slavov, S., & Nikolov, A. (2009). Akusherstvo i ginekologiia, 48(3), 44–46.

- ↑ Rahman RA, Atan IK, Ali A, Kalok AM, Ismail NA, Mahdy ZA, Ahmad S (May 2021). "Use of the Arabin pessary in women at high risk for preterm birth: long-term experience at a single tertiary center in Malaysia". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 21 (1): 368. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-03838-x. PMC 8108362. PMID 33971828.

- ↑ Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, Picciarelli G, Tul N, Zamprakou A, et al. (March 2016). "A Randomized Trial of a Cervical Pessary to Prevent Preterm Singleton Birth". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (11): 1044–1052. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511014. PMID 26981934. S2CID 2957739.

- ↑ Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Poon LC, de Paco Matallana C, Plasencia W, Molina FS, et al. (January 2016). "Cervical pessary placement for prevention of preterm birth in unselected twin pregnancies: a randomized controlled trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 214 (1): 3.e1–3.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.051. PMID 26321037.

- ↑ Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Publications Committee (March 2017). "The role of cervical pessary placement to prevent preterm birth in clinical practice". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 216 (3): B8–B10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.006. PMID 28108157.

External links

- Drakeley AJ, Roberts D, Alfirevic Z (2003). "Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing pregnancy loss in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The Cochrane Collaboration, Cochrane Reviews. 2003 (1): CD003253. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003253. PMC 6991153. PMID 12535466.