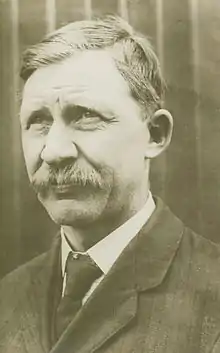

Charles Edward Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 24, 1868 |

| Died | January 30, 1956 (aged 87) |

| Occupation(s) | Mechanic, machinist, inventor |

| Spouse | Henrietta Webbert |

Charles Edward Taylor (May 24, 1868 – January 30, 1956) was an American inventor, mechanic and machinist. He built the first aircraft engine used by the Wright brothers in the Wright Flyer, and was a vital contributor of mechanical skills in the building and maintaining of early Wright engines and airplanes.[1][2]

Biography

[I] always wanted to learn to fly, but I never did. The Wrights refused to teach me and tried to discourage the idea. They said they needed me in the shop and to service their machines, and if I learned to fly, I'd be gadding about the country and maybe become an exhibition pilot, and then they'd never see me again.

— Charlie Taylor

He was born in a log cabin on May 24, 1868, in Cerro Gordo, Illinois, to William Stephen Taylor and Mary Jane Germain.[1] Taylor worked as a binder at the Nebraska State Journal at age 12, later becoming a tool maker. At 24, he met and married Henrietta Webbert, who was from Dayton, Ohio. They had a child and moved to Dayton, where prospects were better. Stoddard Manufacturing Co. hired him to make farm machinery and bicycles. But when the Wright brothers began renting from his wife's uncle a building for their bicycle shop, he went to work for them. Initially, Taylor was hired to fix bicycles, but increasingly took over running of the bicycle business as the Wright brothers spent more time on their aeronautical pursuits. By 1902, they trusted him enough to run the shop in their absence while they went to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to fly gliders.

When it became clear that an off-the-shelf engine with the required power-to-weight ratio was not available in the U.S. for their first engine-driven Flyer, the Wrights turned to Taylor for the job. He designed and built the aluminum-copper, water-cooled, four-cylinder aircraft engine in only six weeks, based partly on rough sketches provided by the Wrights. The cast aluminum block and crankcase weighed 152 pounds (69 kg) and were produced at either Miami Brass Foundry or the Buckeye Iron and Brass Works, near Dayton, Ohio. The Wrights needed an engine with at least 8 horsepower (6.0 kW). The engine that Taylor built produced 12 hp (8.9 kW).

In 1908 Taylor helped Orville build and prepare the "military Flyer" for demonstration to the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia. On September 17, the airplane crashed due to a shattered propeller, seriously injuring Orville and killing his passenger, Army lieutenant Thomas Selfridge. Taylor was among the first to reach the crash. He helped lift Selfridge out of the wreckage, then undid Orville's necktie and opened his shirt as doctors in the crowd pushed their way to the scene. Orville and Selfridge were taken away on stretchers. After that,

Charlie leaned against an upended wing of the wrecked Flyer, buried his face in his arms, and sobbed. A newspaperman tried to comfort him, but he was past comforting until Dr. Watters assured him that the chances for Orville's recovery were good. Then he pulled himself together and took charge of carting the wrecked Flyer back to its shed.[3]

Both Taylor and Navy Lieutenant George Sweet had been scheduled to make their first flights with Orville that day, but both were bumped in order to accommodate Selfridge who had to leave town shortly for Missouri. Despite this accident, Taylor wanted to become a pilot and sought Wilbur and Orville to teach him. The Wrights, reluctant to lose Taylor's services to the world of exhibition flying, discouraged him.

.jpg.webp)

In September, 1909 Taylor accompanied Wilbur, with a new Model A Flyer, to Governor's Island, New York City. Wilbur was to make several over-water flights at the Hudson-Fulton Celebration, demonstrating the airplane to millions of New Yorkers and showcasing the new technology of practical flight. Charlie ably assisted Wilbur, though he did not fly with him. Charlie made sure the engine worked perfectly for the daring and dangerous over-water trips. The pair also installed a watertight canoe to the Flyer's lower wing for buoyancy just in case of an emergency landing in the Hudson River.

Taylor became a leading mechanic in the Wright Company after it was formed in 1909. When Calbraith Perry Rodgers made his trip from Long Island to California in 1911 in his newly bought Wright aircraft, he paid Taylor $70 a week (a large sum at the time) to be his mechanic. Taylor followed the flight by train, frequently arriving at the next rendezvous before Rodgers, to make any required repairs and prepare the aircraft for the next day's flight.[1]

Taylor worked for the Wright-Martin Company in Dayton until 1920. He later moved to California and invested his life savings in several hundred acres of real estate near the Salton Sea, but the venture failed. He returned to Dayton in 1936, and he and Orville helped Henry Ford in the planning, moving and restoration of the Wright family home and one of the Wright brothers' bicycle shops to Ford's Dearborn, Michigan, heritage village about great Americans. Orville also gave Taylor an annuity of $800 a year.[1]

In 1941 Taylor returned to California, finding work in a defense factory. He had a heart attack in 1945 and was no longer able to work. By 1955 his annuity and Social Security income were inadequate and due to his health problems he ended up in the charity ward of the Los Angeles County Hospital. When his destitute plight was publicized by a reporter who found him, the aviation industry raised funds to move him into a private facility.

He died from complications of asthma in San Fernando[4] on January 30, 1956 - eight years to the day after Orville, his friend and employer. Taylor is buried at the Portal of Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation in Burbank, California, a shrine to aviation history.[5]

Legacy

- The FAA's Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award is named in his honor.

- The Charles Taylor Aviation Maintenance Science Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University is named for him.

- Aviation Maintenance Technician Day is observed in 45 U.S. states on May 24, Taylor's birthday.[6]

- Posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1965.

- FAA mechanic certificates now feature Taylor's image rather than the images of the Wright brothers they previously featured, in common with airmen certificates.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Charles Edward Taylor. American National Biography.

- ↑ Charlie Taylor: The Man Aviation History Almost Forgot, March 16, 2012

- ↑ Fred Howard, "Wilbur and Orville", 1998, p.275

- ↑ Milestones, Time, 1956.

- ↑ "C. E. Taylor Laid to Rest With Aviation Pioneers". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 1956.

- ↑ "A Joint Resolution honoring Charles Edward Taylor" (PDF). New Jersey Senate. 2009. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

Further reading

- AMT (Aircraft Maintenance Technology) "Charles E. Taylor: Who is he and why should we honor him?"

- Howard R. DuFour with Peter J Unitt, The Wright Brother's Mechanician, 1997, ISBN 0-9669965-0-X. Published by the author. (196 pages, hardback.)

- "Charlie's Engine", by Tony French in Pilot Celebrates 100 Years of Flying. page 125, Archant Specialist, 2003.

- Aviation Today Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine "My Story: Charles E. Taylor as told to Robert S. Ball"

External links

- Getty Images: Photo: Charlie Taylor, William J. Hammer, Wilbur Wright at the Hudson-Fulton Celebration, 1909

- Bust of Charlie at the USAirForce Museum

- Biography from the National Aviation Hall of Fame

- Archival footage from We Saw It Happen (1953) with Taylor at age 87.