The Yan'an Rectification Movement (simplified Chinese: 延安整风运动; traditional Chinese: 延安整風運動; pinyin: Yán'ān Zhěngfēng Yùndòng)[lower-alpha 1] was a political mass movement led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1942 to 1945.[1] The movement took place in the Yan'an Soviet, a revolutionary base area centered on the remote city of Yan'an. Although it was during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the CCP was experiencing a time of relative peace when they could focus on internal affairs.[2]

The legacies of the Yan'an Rectification Movement proved fundamental to the subsequent history of the Chinese Communist Party, according to Kenneth Lieberthal. These included the consolidation of Mao Zedong's paramount role within the CCP, especially from 1942 to 1944, and the adoption of a party constitution that endorsed Marxist-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought as guiding ideologies.[3] This move formalised Mao's deviation from the Moscow party line and the importance of Mao's alleged 'adaptation of communism to the conditions of China'. The Rectification Campaign was successful in either convincing or coercing the other leaders of the CCP to support Mao. Because the CCP had overcome great odds to grow and develop during this period, the methods employed in Yan'an were looked upon in reverence during Mao's later years. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Mao repeatedly used some of the tactics that had been successful in Yan'an whenever he felt the need to monopolize political power.[4] To a large extent, the Yan'an Rectification Campaign began with the "systematic remolding of human minds."[2]

The United States Joint Publications Research Service estimated that more than 10,000 were killed in the "rectification" process,[5] as the CCP made efforts to attack intellectuals and replace the culture of the May Fourth Movement with that of CCP culture.[6][7][8] The rectification movement is regarded by many as the origin of Mao Zedong's cult of personality.[9][10][11]

Background

In the 1930s the remote region of Yan'an had not experienced the same turmoil and hostilities as other mainland territories. Situated in northwest China, the area was also difficult to attack. CCP members mostly arrived there after the Long March (1934–1935). The area was known as a territory of camaraderie without corruption, though the Rectification Movement essentially changed everything.[12]

According to official CCP sources, the purpose of the Rectification Campaign was to give a basic grounding in the Marxist theory and Leninist principles of party organization to the thousands of new members who had joined the CCP during its expansion after 1937. A second, equally important aspect of the movement was the elimination of the blind imitation of Soviet models, obedience to Soviet directives (mostly communicated to China via the Communist International), and "empiricism". Mao emphasized that the campaign aimed at "rectifying mistaken ideas" and not the people who held them.[13]

Modern research by Chinese and Western scholars, in particular the interpretation of history professor Gao Hua in his work "How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan'an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945, have focused on the political nature of the Rectification Movement.[1] Modern scholars have increasingly viewed the movement as being initiated by Mao in order to ensure his status as paramount leader of the CCP. According to Gao, the Rectification Movement had four purposes:

- To end the veneration of "Party intellectuals who had studied in the Soviet Union and those who had been educated abroad or through “standard” education within China", ultimately forming the new fashion: "Being well-read was wrong-headed, and ignorance of the classics was commendable."[1]: 363

- To purge the May Fourth "notions of freedom, democracy, and individual liberation among Party intellectuals", establishing the concept of "the leader and the collective above all, and the individual as negligible."[1]: 364 Mao first "drew on the support of the liberal intellectuals in the Party to encircle and suppress the Soviet faction", then reinstated the Soviet faction and used them to "to join with [Mao] in suppressing the remnants (the liberal intellectuals) of the 'May Fourth' influence in the Party."[1]: 364

- To theorize the concept of "peasants as the principal force of the Chinese Revolution"[1]: 364

- To build up Party ideology and organization by using "the Communist Party’s theory of inner-Party struggle", employing "ideological persuasion and coercion to forge an ideal Communist 'New Man' who combined loyalty and obedience with a fighting spirit."[1]: 364

Throughout the Rectification Campaign, Yan'an was not seriously threatened by either the Japanese or the Nationalists. With the Soviets at war with Nazi Germany and unable to intervene, Mao seized the opportunity in Yan'an to "go to work" on his Party and "mold it into an unquestioning machine" in preparation for the all-out civil war against the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek that was expected to follow the defeat of the Japanese. (This is according to Jung Chang and Jon Halliday,[12] whose treatment of Mao has been regarded as flawed by some China scholars.[14])

The Yan'an era had a profound effect on the CCP and its future fortunes. When the Communists completed the Long March, the CCP was a relatively small band of less than 10,000 worn out troops from the south, displaced to an isolated and poor area in the hinterlands of northern China. By the end of the Yan'an era, however, the CCP's forces had grown to nearly 2.8 million members, and it governed nineteen base areas that contained a population of nearly one hundred million people.[4]

Remolding of the volunteer corps

Party membership was strongly shaped by the devastation of the final battles for the Jiangxi Soviet, the Long March.[4] With only a few original members of the CCP surviving until the end of the Yan'an period, the Party as of the mid-1940s consisted of 90% peasants recruited from the base areas of north China.[12]

The mostly young volunteers who arrived in Yan'an after the Long March were "vital to Mao because they were relatively well educated, and he needed competent administrators to staff his future regime". Most of the Long Marchers and rural recruits from within the Communist bases were illiterate peasants. It was these more recent volunteers who were Mao's primary "target".[12]

A large number of the young volunteers congregated in Yan'an, the capital of Mao's Communist Party. By the time Mao Zedong started his drive to "condition" them, around 40,000 had arrived. Most were in their late teens and early twenties, had joined the CCP in territories controlled by the Nationalists, and later departed to Yan'an. They were excited at reaching what was called a "revolutionary Mecca." One young volunteer described his feeling: "At last we saw the heights of Yenan city. We were so excited we wept. We cheered from our truck ... We started to sing the "Internationale", and Russia's Motherland March.'"[12]

The Party's leadership, however, reflected the CCP's origins south of the Yangtze River, and was at best supplemented by the intellectuals who trekked out to Yan'an to join the Party during the war against Japan. The Yan'an Rectification Campaign was also directed towards the indoctrination of older Communist Party personnel. "The Party chose to re-emphasize its basic principles during this period, in an evident determination to maintain its Leninist foundations in the midst of all the changes brought about by the war-time shift to the united front."[15]

The Yan'an Rectification Campaign improved the discipline, education, and organization of the membership of the CCP. Having lost many veterans before and during the Long March, the Communists found new sources of recruits among urban youth, students, and intellectuals. Alienated from the Nationalist government and doubting its resolve in resisting the Japanese, many new CCP volunteers were drawn by communist propaganda that portrayed the CCP as "the saviors of the nation", promising democracy and liberal reforms. As a result, hundreds of thousands of students, teachers, artists, writers, and journalists poured into Yan'an, seeking a revolutionary career. In Marxist classification these new recruits were of petit bourgeois origin. Their enthusiasm and various sorts of expertise were useful for the revolution, but only after they had undergone a thorough political reeducation and ideological reform.[2]

The process of indoctrination extended even to the cadres who had survived the Long March and "proven their revolutionary credibility." All Party members were reeducated with the newly established "Mao Zedong Thought" in order to ensure their high compliance with the new leadership and the new party ideology.[2] In order to secure his power, Mao supported his political authority with ethical and moral rhetoric.

Rise of Mao

The Yan'an rectification saw Mao consolidate his position of preeminence in the CCP. To do this he undertook a "thought-reform campaign" from 1942 to 1944. The effort was partly a reflection of Mao's wish to eradicate Soviet influence. Under the conditions of independently operating Communist areas and incessant warfare, Mao could not rely on discipline alone to guarantee obedience in the CCP ranks. In order to ensure the Party's obedience to his orders, Mao developed the techniques of the Rectification Campaign to implement 思想改造 sīxiǎng gǎizào "thought reform” or “ideological transformation". Mao's tactics often included isolating and attacking dissenting individuals in "study groups."[4]

Operational principles

The CCP established numerous schools, formulating a new type of educational system. Among these schools were the Anti-Japanese Military and Political University, the Lu Xun Academy of the Arts, the Northwest Public School, the Central Party School, the Academy of Marxism-Leninism, the Women's University, Yan'an University, and the Academy of the Nationality, as well as a number of special training programs.[2] All veterans and new recruits had to be enrolled and educated in one of these institutions, in accordance with their previous training or their expertise, before they could be trusted with assignment to party and government positions.[2]

At the end of the Yan'an Rectification Campaign the CCP had developed an operational set of principles and practices that differed greatly from the centralized, functionally specialized, hierarchical, command-oriented approach imposed by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. In what some authors have labeled the "Yan'an complex," the CCP emphasized a combination of qualities that can be summed up as:

- decentralized rule with flexibility allowed to local leaders;[4]

- the importance of ideology in keeping cadres loyal;

- a strong preference for officials whose leadership spans a range of areas;

- stress on developing and maintaining close ties with the local population;

- focus on egalitarianism and simple living among officials.[4]

These became deeply held values of the CCP, and years later became central to the party's mythology that reminisced about the success of the Yan'an era.[4]

Thought reform

During the Yan'an Rectification Campaign, more sophisticated techniques of thought control were used than had been previously attempted in China. Relying on criticism, self-criticism, "struggle", confession, and the content of the Marxist doctrine, these methods were heavily influenced by contemporary Soviet practices of "thought reform".[16]

Under the guidance of a group leader, an individual, as part of a larger "study group", would study Marxist documents to understand "key principles," and then relate those principles to their own lives in a "critical, concrete, and thoroughgoing way."[4] Other members of the group put the individual under "extraordinary pressure" to examine fully his or her most deeply held views, and to do so in the presence of the group.[4] The individual then had to write a full "self-confession." Other group members isolated the individual during this process. Only when the confession was accepted would the person be drawn back into an accepted position in the group and in the larger society.[4]

These techniques of pressure, ostracism, and reintegration were particularly powerful in China, where the culture puts great value on "saving face", protecting one's innermost thinking, and above all, identifying with a group.[17] Individuals put through thought reform later described it as excruciating. The resulting changes in views were not permanent, but the experience overall seriously affected the lives of those who went through it. The CCP used these same types of techniques on millions of Chinese after 1949.[17]

A campaign in three phases

Phase I

The preparatory phase of the Rectification Campaign lasted from May 1941 to February 1942. The Campaign began on February 1, 1942, under Mao Zedong with his speech "Reform in Learning, the Party and Literature."[8] A book entitled "Documents of the Rectification Campaign" was published and circulated internally. This book included essays including Mao's "Combat Liberalism" and Liu Shaoqi's "How to be a Good Communist."[8]

In July and August 1942 the CCP issued the decision for "Research and Analysis" and "Improvement of Party Membership." The leading team for the campaign was established with Mao as director and Wang Jiaxiang deputy director. In 1942 the CCP had 800,000 members, of which only a small group of approximately 150 members usually made all major decisions.[13]

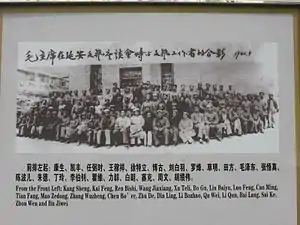

Although Mao took charge of the leadership of the CCP after the Zunyi Conference, he was not yet in a dominant position. Even after Mao won a power struggle with Zhang Guotao, he was still one among many senior leaders, including Zhou Enlai, Wang Ming and Zhang Wentian. Before the Rectification Campaign Mao's contribution to the revolution in rural areas, and even his status as a senior leader, was doubted by other members of the CCP, including Xiang Zhongfa, Zhang Guotao, Li Lisan, and intellectuals such as Zhou Enlai, Qu Qiubai and the 28 Bolsheviks. Unlike his rival Wang Ming, Mao was not recognized by the Communist International as one of the CCP's preferred leaders.

During this preparatory phase, Mao used his political skills to consolidate his power base.[18]: 37 By manipulating the political climate in Yan'an, Mao was able to break up the alliance of his opponents, most notably Zhang Guotao and the members of the 28 Bolsheviks, and to eliminate his rivals one by one.

Phase II

The Rectification Campaign was officially launched in 1942. Since the 4th Plenum Meeting of 6th National Congress of the CCP (1928), the 28 Bolsheviks began to take control of the CCP with the help of the Comintern. To gain the support of those who might potentially oppose him, Mao labeled his rivals as comrades who were supporting the wrong cause. This rejection of ad hominem arguments made him appear politically and mentally superior to his political enemies. Mao categorized his rivals, or potential rivals, into two groups.

One group was labeled "dogmatists," comprising Wang Ming, the 28 Bolsheviks, and those who had studied abroad and were deeply influenced by foreign theories, including Liu Bocheng, Zuo Quan, and Zhu Rui. The other group was labeled "empiricists", whose members included Zhou Enlai, Ren Bishi, Peng Dehuai, Chen Yi, Li Weihan, Deng Fa, and any other senior leaders who supported Wang Ming. Mao forced these leaders to criticize each other and self-criticize in rounds of meetings. Every one of them wrote reports of confession and apologies for their mistakes. Those who had produced self-criticisms were later persecuted according to their own confessions.

Mao set up the Central General Study Committee to be in charge of the movement. This committee was run by Mao's close allies Kang Sheng, Li Fuchun, Peng Zhen, and Gao Gang, and later included Liu Shaoqi. This Committee temporarily replaced the politburo and secretariat, running daily operation for the CCP and making it one of the most powerful administrative bodies at that time. The Committee gave Mao the ability to exercise authoritarian power without being limited by elections and term limits. The earlier collective decision-making system of CCP center was abandoned, and Mao turned the government of Yan'an into his own dictatorship.[9][10][11]

From February 1942 to October 1943, the Rectification Campaign reached its peak. Mao gave the lecture "Improving the Party Work Style and Thought" in the opening ceremony at the Central Party School.[19] The lecture "Against Party Stereotype-Writing" in the cadre party of Yan'an in February 1942 interpreted the aim and policy of the movement in full detail - the event included thousands of cadres from the party.[19] In this lecture, Mao Zedong declared:[20]

Why must there be a revolutionary party? There must be a revolutionary party because our enemies still exist, and furthermore there must not be only an ordinary revolutionary party but a Communist revolutionary party.

Phase III

The third phase of the Rectification Campaign lasted from October 1943 to 1944 or April 1945, depending on sources. It is generally known as the "Summing up party history" phase.[19] Senior leaders restudied party history and attempted to reach agreements on major issues by admitting to "errors".[19] The 1943 portion of the campaign included a "Rescue Campaign" that focused on group retribution. In the Rescue Campaign, members would write about their own confessions, often pointing fingers at other members to save themselves from other people's false allegations toward them.[8] The Rescue Campaign soon became a circular cycle of false guilt and fake reenactments sending many innocent people to death via needless witch hunts.

One of the members crucial to carrying out the Rectification Movement was the secret police boss Kang Sheng.[8] Wang Ming was one of the main members singled out and forced to confess to having "errors."[13] Wang was set up by his former friend Bo Gu, who coincidentally was also later condemned for pursuing an "erroneous leftist line" in Jiangxi. Zhang Wentian also made self criticisms.[13] Wang Shiwei became a well known victim.

Some CCP members thought Mao would also accept genuine criticism and spoke their true feelings of anger over hierarchy and inequality in Yan'an. The most famous came from Wang Shiwei, a journalist and intellectual known for his belief in "democracy and science." Wang wrote an essay denouncing the hierarchy, bureaucracy, and inegalitarian distribution of resources in Yan'an. The essay irritated Mao greatly, and Wang was labeled a Trotskyist. Wang was arrested by the Central Social Department, modeled off the Soviet Union's OGPU,[5] and beheaded in 1947.

Under the leadership of Peng Zhen, the Central Political School of the CCP began to carry out the Rectification Campaign among its students. Massive numbers of party members were forced to write reports of confession and self-criticism.[8] The Central General Study Committee ordered people to report on their daily habits and speech. This stage was known as the "Salvation Stage". The Salvation Stage was the extension of the Maoist anti-Trotskyist movement and the censorship of newcomers who had come from the areas governed by the Kuomintang. The Central Social Department took control of the movement and turned it into a mass persecution in 1943.

Thousands of people, especially those new members who came from areas governed by KMT, were purged, kept in custody, censored, mentally and physically tortured, and occasionally executed.[1] Many of them were labeled as "spies of the Kuomintang" or "anti party activists". Not only were they themselves humiliated, but also their family members and relatives.[1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Also known as the Zhengfeng or Cheng Feng from its transliteration

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hua, Gao; Mosher, Stacy; Jian, Guo (2018). How the Red Sun Rose: The Origins and Development of the Yan'an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvbtzp48. ISBN 978-962-996-822-9. JSTOR j.ctvbtzp48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cheng, Yinghong (2009). Creating the "New Man": From Enlightenment Ideals to Socialist Realities. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 59–70. ISBN 978-0-8248-3074-8. JSTOR j.ctt6wqzq7.

- ↑ Lieberthal (2003), p. 46

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lieberthal, Kenneth (2004). Governing China: From Revolution Through Reform. W. W. Norton. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-0-393-92492-3.

- 1 2 US Joint Publication research service. (1979). China Report: Political, Sociological and Military Affairs. Foreign Broadcast information Service. No ISBN digitized text March 5, 2007

- ↑ Fairbank, John K.; Feuerwerker, Albert, eds. (1986-07-24). The Cambridge History of China (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/chol9780521243384. ISBN 978-1-139-05480-5.

- ↑ Borthwick, Mark (1998). Pacific Century: The Emergence of Modern Pacific Asia. Avalon. ISBN 978-0-8133-4355-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Apter, David Ernest; Saich, Tony (1994). Revolutionary Discourse in Mao's Republic. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-76780-5.

- 1 2 Selden, Mark (1995). "Yan'an Communism Reconsidered". Modern China. 21 (1): 8–44. doi:10.1177/009770049502100102. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189281. S2CID 145316369.

- 1 2 Tokuda, Noriyuki (1971). "Yenan Rectification Movement: Mao Tse-Tung's Big Push toward Charismatic Leadership during 1941-1942". The Developing Economies. 9: 83–99. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1049.1971.tb00463.x.

- 1 2 He, Fang. ""延安整风"与个人崇拜". Modern China Studies (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2020-07-14. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chang, Jung (2008-06-20). Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-0649-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Short, Philip. Mao: a Life. ISBN 0-8050-6638-1

- ↑ Hamish McDonald (2005-10-08). "A swan's little book of ire". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ Brandt, Conrad; Schwartz, Benjamin I.; Fairbank, John King (1952-12-31). A Documentary History of Chinese Communism. Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674734050. ISBN 978-0-674-73029-8.

- ↑ Lifton, Robert J. (November 1956). "Thought Reform of Chinese Intellectuals: A Psychiatric Evaluation". The Journal of Asian Studies. 16 (1): 75–88. doi:10.2307/2941547. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2941547. S2CID 144589833.

- 1 2 Lieberthal (2003), p. 47

- ↑ Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. New Haven: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3006z6k. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. JSTOR j.ctv3006z6k. OCLC 1348572572. S2CID 253067190.

- 1 2 3 4 Garver, John W. (1988-09-08). Chinese-Soviet Relations, 1937-1945: The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536374-6.

- ↑ Li, Lincoln (1994-01-01). Student Nationalism in China, 1924-1949. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1749-2.

Further reading

| Library resources about Yan'an Rectification Movement |

- Gao, Hua. (2000). How the Red Sun Rose: The Origin and Development of the Yan'an Rectification Movement, 1930–1945. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. ISBN 9789629968229