The July 1995 Chicago heat wave led to 739 heat-related deaths in Chicago over a period of five days.[1] Most of the victims of the heat wave were elderly poor residents of the city, who did not have air conditioning, or had air conditioning but could not afford to turn it on, and did not open windows or sleep outside for fear of crime.[2] The heat wave also heavily impacted the wider Midwestern region, with additional deaths in both St. Louis, Missouri[3] and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[4]

Weather

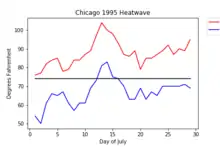

The temperatures soared to record highs in July with the hottest weather occurring from July 12 to July 16. The high of 106 °F (41 °C) on July 13 was the second warmest July temperature (warmest being 110 °F (43 °C) set on July 23, 1934) since records began at Chicago Midway International Airport in 1928. Nighttime low temperatures were unusually high — in the upper 70s and lower 80s °F (about 26 °C).

The humidity made a large difference for the heat in this heat wave when compared to the majority of those of the 1930s, 1988, 1976–78 and 1954–56, which were powered by extremely hot, dry, bare soil and/or air masses which had originated in the desert Southwest. Each of the above-mentioned years' summers did have high-humidity heat waves as well, although 1988 was a possible exception in some areas. Moisture from previous rains and transpiration by plants drove up the humidity to record levels and the moist humid air mass originated over Iowa previous to and during the early stages of the heat wave. Numerous stations in Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois and elsewhere reported record dew point temperatures above 80 °F (27 °C) with a peak at 90 °F (32 °C) with an air temperature of 104 °F (40 °C) making for a 153 °F (67 °C) heat index reported from at least one station in Wisconsin (Appleton)[5] at 5:00 pm local time on the afternoon of 14 July 1995, a probable record for the Western Hemisphere; this added to the heat to cause heat indices above 130 °F (54 °C) in Iowa and southern Wisconsin on several days of the heat wave as the sun bore down from a cloudless sky and evaporated even more water seven days in a row.

A few days after, the heat moved to the east, with temperatures in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania reaching 100 °F (38 °C) and in Danbury, Connecticut, 106 °F (41 °C) which is Connecticut's highest recorded temperature.[6] North of the border, Toronto, Ontario reached 37 °C (99 °F), when coupled with record high humidity from the same airmass resulted in its highest ever humidex value of 50 C (122 F).

Dewpoint records are not as widely kept as those of temperature, however, the dew points during the heat wave were at or near national and continental records.

Analysis

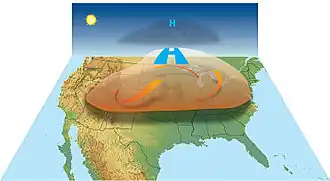

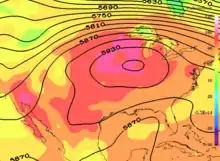

The heat wave was caused by a large high pressure system that traversed across the midwest United States. This system was consistently producing maximum temperatures in the 90's °F (32-38 °C) during the day with minimum temperatures still remaining as high as the 80s °F (27-32 °C) at night, which is abnormal for midwest summer months.[7] The system also brought extremely low wind speeds, along with high humidity. In the MERRA-2 and the ERAI meteorological reanalyses, the system (see figure) moved eastward, becoming indistinguishable by July 18.

Victims

Eric Klinenberg, author of the 2002 book Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, has noted that the map of heat-related deaths in Chicago mirrors the map of poverty.[2][8] Most of the heat wave victims were the elderly poor living in the heart of the city, who either had no air conditioning, or had air conditioning but could not afford to turn it on. Many older citizens were also hesitant to open windows and doors at night for fear of crime.[9] Elderly women, who may have been more socially engaged, were less vulnerable than elderly men. By contrast, during the heat waves of the 1930s, many residents slept outside in the parks or along the shore of Lake Michigan.[2]

Because of the nature of the disaster, and the slow response of authorities to recognize it, no official "death toll" has been determined. However, figures show that 739 additional people died in that particular week above the usual weekly average.[10] Further epidemiologic analysis showed that Black residents were more likely to die than White residents, and that Hispanic residents had an unusually low death rate due to heat. At the time, many Black residents lived in areas of sub-standard housing and less cohesive neighborhoods, while Hispanic residents at the time lived in places with higher population density, and more social cohesion.[2]

Mortality displacement refers to the deaths that occur during a heat wave that would have occurred anyway in a near future, but which were precipitated by the heat wave itself. In other words, people who are already very ill and close to death (expected to die, for instance, within days or a few weeks) might die sooner than they might have otherwise, because of the impact of the heat wave on their health. However, because their deaths have been hastened by the heat wave, in the months that follow the number of deaths becomes lower than average. This is also called a harvesting effect, in which part of the expected (future) mortality shifts forward a few weeks to the period of the heat wave. Initially some public officials suggested that the high death toll during the weeks of the heat wave was due to mortality displacement; an analysis of the data later found that mortality displacement during the heat wave was limited to about 26% of the estimated 692 excess deaths in the period between June 21 and August 10, 1995. Mortality risks affected Black residents disproportionally. Appropriately targeted interventions may have a tangible effect on life expectancy.[11]

In August, the remains of forty-one victims whose bodies had not been claimed were buried in a mass grave in Homewood, Illinois.[12]

Aggravating factors

Impacts in the Chicago urban center were exacerbated by an urban heat island that raised nocturnal temperatures by more than 2 °C (3.6 °F).[13] Urban heat islands are caused by the concentration of buildings and pavement in urban areas, which tend to absorb more heat in the day and radiate more of that heat at night into their immediate surroundings than comparable rural sites. Therefore, built-up areas get hotter and stay hotter.

Other aggravating factors were inadequate warnings, power failures, inadequate ambulance service and hospital facilities, and lack of preparation.[14] City officials did not release a heat emergency warning until the last day of the heat wave. Thus, such emergency measures as Chicago's five cooling centers were not fully utilized. The medical system of Chicago was severely taxed as thousands were taken to local hospitals with heat-related problems.

Another powerful factor in the heat wave was that a temperature inversion grew over the city, and air stagnated in this situation. Pollutants and humidity were confined to ground level, and the air was becalmed and devoid of wind. Without wind to stir the air, temperatures grew even hotter than could be expected with just an urban heat island, and without wind there was truly no relief. Without any way to relieve the heat, even the insides of homes became ovens, with indoor temperature exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) at night. This was especially noticeable in areas which experienced frequent power outages. At Northwestern University just north of Chicago, summer school students lived in dormitories without air conditioning. In order to ease the effects of the heat, some of the students slept at night with water-soaked towels as blankets.

The scale of the human tragedy sparked denial in some quarters, grief and blame elsewhere.[2] From the moment the local medical examiner began to report heat-related mortality figures, political leaders, journalists, and in turn the Chicago public have actively denied the disaster's significance. Although so many city residents died that the coroner had to call in seven refrigerated trucks to store the bodies, skepticism about the trauma continues today. In Chicago, people still debate whether the medical examiner exaggerated the numbers and wonder if the crisis was a "media event."[8] The American Journal of Public Health established that the medical examiner's numbers actually undercounted the mortality by about 250 since hundreds of bodies were buried before they could be autopsied.[10]

Environmental racism

Various aggravating factors in this context have informed discussions about environmental racism, environmental injustice within a racialized context.

In the context of the 1995 Chicago heat wave, principles of environmental racism have been used to better understand the hugely unequal death rates between various groups in the Chicago population. Out of the 739 heat related deaths attributed to the heat wave, it was found that Black citizens died at a much higher rate than their white peers. Further, this finding was statistically significant beyond the consideration of increased rate of death in impoverished areas.[15]

In 2018, filmmaker Judith Hefland created Cooked: Survival by Zip Code, a documentary exploring the unequal death rates observed during the 1995 heat wave. Cooked examines the factors that most directly contributed to these unequal death rates, and posits that such a crisis was not a one time catastrophe, but rather a dangerous trend occurring beyond Chicago.

This documentary examined the particularly devastating impact of various aggravating factors on Black communities. Most directly, the lack of adequate warning and failure to utilize pre-existing cooling centers disadvantaged impoverished groups, and caused particularly devastating effects in Chicago's poorest areas. Hefland warns that Chicago can serve as a model for the environmental racism present in many American cities.

Urban heat islands still exist throughout the United States and beyond, and impoverished, minority groups still disproportionately occupy these at risk neighborhoods. With the number of climate disasters increasing five fold[16] over the past 50 years, the risk to these groups increases as well, and social movements calling for environmental justice have grown in turn.

Statistics

Chicago's daily low and high temperatures in 1995:

- July 11: 73–90 °F (23–32 °C)

- July 12: 76–98 °F (24–37 °C)

- July 13: 81–106 °F (27–41 °C)

- July 14: 84–102 °F (29–39 °C)

- July 15: 77–99 °F (25–37 °C)

- July 16: 76–94 °F (24–34 °C)

- July 17: 73–89 °F (23–32 °C)

Statistics about the averaged July monthly average temperatures from 1960–2016 give us a mean of 74 degrees F and a standard deviation of 2.7.[17]

During the week of the heat wave, there were 11% more hospital admissions than average for comparison weeks and 35% more than expected among patients aged 65 years and older. The majority of this excess (59%) were treatments for dehydration, heat stroke, and heat exhaustion.[18]

Wet-bulb temperatures

Wet-bulb temperatures during the heat wave reached 85 °F (29 °C) in some places.[19] A wet-bulb temperature of 95 °F (35 °C) may be fatal to healthy young humans if experienced over six hours or more for children one month of age as well as the elderly 70 and over.[20]

References

- ↑ Dematte, Jane E.; et al. (1 August 1998). "Near-Fatal Heat Stroke during the 1995 Heat Wave in Chicago". Annals of Internal Medicine. 129 (3): 173–181. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00001. PMID 9696724. S2CID 5572793.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Klinenberg, Eric (2002). Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. ISBN 0-226-44322-1.

- ↑ Smoyer, K.E. (September 1998). "A comparative analysis of heat waves and associated mortality in St. Louis, Missouri – 1980 and 1995". International Journal of Biometeorology. 42 (1): 44–50. Bibcode:1998IJBm...42...44S. doi:10.1007/s004840050082. PMID 9780845. S2CID 20120285.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1996-07-21). "Heat-Wave-Related Mortality – Milwaukee, Wisconsin, July 1995". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 45 (24): 505–7. PMID 9132565.

- ↑ Burt, Christopher C. (August 11, 2011). "Record Dew Point Temperatures". Weather Underground.

- ↑ Gendreau, LeAnne; Connors, Bob; Hanrahan, Ryan (2011-07-21). "Temp Breaks Record at 103". NBC Connecticut.

- ↑ Data, US Climate. "Climate Chicago – Illinois and Weather averages Chicago". www.usclimatedata.com. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- 1 2 Klinenberg, Eric (2002-07-30). "Dead Heat: Why don't Americans sweat over heat-wave deaths?". Slate.com.

- ↑ Changnon, Stanley A.; Kunkel, Kenneth E.; Reinke, Beth C. (1996). "Impacts and Responses to the 1995 Heat Wave: A Call to Action". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 77 (7): 1497–1506. Bibcode:1996BAMS...77.1497C. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<1497:IARTTH>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- 1 2 Whitman, S.; et al. (1997). "Mortality in Chicago attributed to the July 1995 heat wave". American Journal of Public Health. 87 (9): 1515–1518. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1515. PMC 1380980. PMID 9314806.

- ↑ Kaiser, Reinhard; et al. (2007). "The Effect of the 1995 Heat Wave in Chicago on All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality". American Journal of Public Health. 97 (1): 158–162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.100081. PMC 1854989. PMID 17413056.

- ↑ "Alone and Forgotten, 41 Unclaimed Heat Victims Buried in Mass Grave". Associated Press. August 26, 1995. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ↑ Kunkel, Kenneth E.; Changnon, Stanley A.; Reinke, Beth C.; Arritt, Raymond W. (1996). "The July 1995 Heat Wave in the Midwest: A Climatic Perspective and Critical Weather Factors". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 77 (7): 1507–1518. Bibcode:1996BAMS...77.1507K. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<1507:TJHWIT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- ↑ Duneier, Mitchell (2004). "Scrutinizing the Heat: On Ethnic Myths and the Importance of Shoe Leather". Contemporary Sociology. American Sociological Association. 33 (2): 139–150. doi:10.1177/009430610403300203. JSTOR 3593666. S2CID 143668374.

- ↑ "Climate History: July 1995 Chicago-Area Heat Wave | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) formerly known as National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)". www.ncdc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ↑ "Climate change: Big increase in weather disasters over the past five decades". BBC News. 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ↑ "Climate Normals | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) formerly known as National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)". www.ncdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- ↑ Semenza, Jan C.; et al. (1999). "Excess hospital admissions during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 16 (4): 269–277. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00025-2. PMID 10493281.

- ↑ "The Deadly Combination of Heat and Humidity". The New York Times. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Luis, Alan (March 9, 2022). "Too Hot to Handle: How Climate Change May Make Some Places Too Hot to Live". NASA. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

External links

- Chicago Tribune photos from the heatwave

- Interview with Eric Klinenberg

- The 1995 Heat Wave in Chicago Illinois

- Semenza, Jan C.; C.H. Rubin; K.H. Falter; J.D. Selanikio; W.D. Flanders; H.L. Howe; J.L. Wilhelm (1996-07-11). "Heat-Related Deaths during the July 1995 Heat Wave in Chicago". New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1056/NEJM199607113350203. PMID 8649494.

- Bernard, Susan M.; M.A. McGeehin (September 2004). "Municipal Heat Wave Response Plans". American Journal of Public Health. American Public Health Association. 94 (9): 1520–2. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1520. PMC 1448486. PMID 15333307.

- When Weather Changed History: Deadly Heat (Television). The Weather Channel. 18 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- Hefland's Documentary Survival by Zipcode