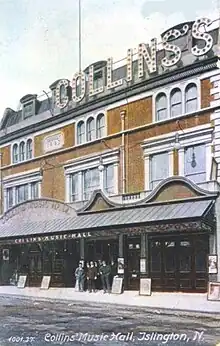

Collins's (sometimes written as Collins') was a music hall in Islington, north London. It opened in 1863, named after its original proprietor, the comedian, singer and impresario Sam Collins. He died not long after the hall opened, and after continuing under his widow and others, the hall was rebuilt and extended in 1897, with a much enlarged capacity. Collins's, like other music halls and variety theatres, declined in the years after the Second World War; it closed in 1958 after a fire.

Among the performers seen at Collins's were Tom Costello, Joe Elvin, Harry Randall, Harry Tate and Bessie Wentworth. Later performers there included Wilkie Bard, George Robey, Charlie Chaplin, Gracie Fields and Tommy Trinder.

The façade survived the 1958 fire and from 1994 onwards it has fronted a large bookshop built behind it.

Background and opening

Collins's was built on a west-facing site at Islington Green, between Upper Street and Essex Road. A public house with a small theatre had reportedly been opened there in 1794, and by the 1840s was trading as the Lansdowne Arms and Music Hall.[1] In 1861 Sam Collins was appearing at the nearby Philharmonic Hall and discovered the Lansdowne. Collins, whose original surname was Vagg, was a popular performer, who – although he was English – was best known for his performance as an Irishman, singing comic songs such as "Limerick Races", "Paddy O'Blarney" and "Beautiful Biddy of Sligo".[2][3] He was also a theatre manager, having bought a pub in Marylebone High Street and rebuilt the adjacent auditorium as Collins's Music Hall in 1858.[4] At the time when he encountered the Islington premises the hall was shut and its licence to present music had lapsed.[5][6] Collins bought both the pub and the hall, selling his establishment in Marylebone to finance the purchase and reconstruction of the Islington premises.[5]

Collins had some difficulty at first in obtaining an official licence to present music,[6] but was successful in October 1863.[7] His hall opened on 4 November 1863.[8] The Era described it:

The Islington Times reported, "Mr. Collins' new Music Hall was opened with great éclat. No expense was spared to provide an entertainment that should amply delight the most exacting, and we were pleased to observe that the efforts of the proprietor had not only attracted a crowded house, but fully succeeded in amusing them while there."[9]

1865 to 1897

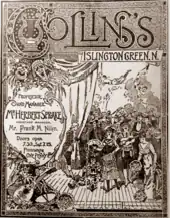

Collins died after a brief illness in 1865, aged 39. His widow, Annie, née Dobson, carried on the business with the help of Harry Sydney, a family friend. Sydney died in 1870, after which Henry Watts, Annie's second husband, took over, running the hall throughout the decade.[10] Watts was followed by his nephew, Herbert Sprake, a man of strict principles, who would not tolerate impropriety in his theatre. He was described as "ever on the alert to detect the double entendre", and as a result of his strictness Collins's acquired the nickname "The Chapel on the Green".[11] This did not diminish the hall's public appeal or Sprake's considerable popularity among the performers he engaged.[11] A local newspaper described the hall as "amazingly popular".[11]

In the 1880s Collins's had its last regular chairman, John Read, who introduced the acts from his desk at the side of the proscenium, facing the audience. This was the norm in music halls of the day, but by the end of the decade it had become the practice, at Collins's and elsewhere, to display at the side of the stage the details of each act, and the chairman's role became redundant.[1]

New theatre, 1897

The hall continued under Sprake's management until 1897, when he retired and sold his interest to a consortium. He bowed out with an all-star programme that included Tom Costello, Joe Elvin, Harry Randall, Harry Tate and Bessie Wentworth.[12] The regard with which he was held by his peers was shown by the banquet marking his retirement, given by his fellow music-hall proprietors and other friends and admirers, to celebrate "twenty-five years of conscientious and meritorious work as a caterer for the healthy amusement of the people".[13]

The consortium, Richards, Burney, Grimes and Dearing, resolved to rebuild and extend the hall. They commissioned Ernest A. E. Woodrow, a former pupil of C. J. Phipps and later architect of the Camberwell Palace of Varieties and the Grand Theatre, Clapham. The Era described his building:

The capacity of the auditorium was greatly increased to a little less than 1,800, about a third of which was in the gallery.[15] The venue was relaunched as "Collins's Theatre of Varieties", although the public in general continued to call it Collins's Music Hall.[16]

20th century

The new house prospered at first, with top stars such as Wilkie Bard and George Robey. After the initial years of the new hall, there followed what the historian Bill Manley describes as "an unsettled period till after the Great War".[16] Attractions ranged from boxing tournaments,[17] to Fred Karno's troupe, in which the young Charlie Chaplin played an upper-class drunk in the sketch "Mumming Birds". Gracie Fields made her first London appearance at Collins's in a touring revue.[16]

During this period the name of the theatre was changed to the "Islington Hippodrome"; it reverted to Collins's in 1919.[16]

After the war the management of the theatre experimented with a season of melodramas, given by a resident company.[1] In 1920 Charles Gulliver, managing director of the London Palladium took over the management of Collins's. Manley comments that this seemed to promise improvements, but Gulliver left after five years "and nothing spectacular had happened; neither did it in the next seven except for the Christmas pantomimes and some plays".[16]

The house reopened as a variety theatre in 1931. Veterans such as Kate Carney and newcomers such as Tommy Trinder featured on the bills.[16] In the later 1930s an attempt was made to establish a repertory company at Collins's, presenting favourite old plays including Mr Wu, Tilly of Bloomsbury, The Ringer and White Cargo.[18]

In 1939 the comedian and producer Lew Lake took over, but within weeks he died in his flat above the theatre.[19] After his death his widow took over, followed by their son, who remained in charge until he died shortly before the theatre closed in 1958.[20]

After the interior of the building was seriously damaged by fire in September 1958 it did not reopen and was used as a timber store. Plans to restore the auditorium came to nothing and in 1994 the local authority approved an application by Waterstones to turn the premises into a bookshop. The 1897 façade remained in place and has been preserved by Waterstones.[21]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ 21.3 x 13 x 9.1 metres

References

- 1 2 3 Manley, p. 123

- ↑ "The Late Mr Sam Collins", Clerkenwell News, 2 June 1865, p. 2

- ↑ "Sam Collins' Irish Comic Song Book", National Library of Ireland. Retrieved 8 July 2023

- ↑ Baker, p. 17

- 1 2 Manley, p. 15

- 1 2 "Middlesex Sessions", The Sun, 11 October 1862, p. 3

- ↑ "The Lansdowne Arms", Islington Times, 14 October 1863, p. 3

- 1 2 "London Music Halls", The Era, 8 November 1863, p. 5

- ↑ "Mr. Samuel Collins' Music Hall", Islington Times, 11 November 1863, p. 3

- ↑ "Famous London Music Hall", Morning Leader, 1 June 1910, p. 3

- 1 2 3 "Merrie Villager's Log", Holloway Press, 16 April 1932, p. 4

- ↑ "Collins's (Islington Green)", London and Provincial Entr'acte, 3 July 1897, p. 10

- ↑ "Presentation to Mr and Mrs H. Sprake", The Era, 16 October 1897, p. 20

- ↑ "The New Collins's, Islington", The Era, 25 December 1897, p. 16

- ↑ "A New Theatre of Varieties", The Evening Standard, 24 December 1897, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Manley, p. 17

- ↑ "Collins's Music Hall", Boxing World, 12 February 1910, p. 6

- ↑ "Music Hall Repertory", Daily News, 25 January 1937, p. 9

- ↑ "Lew Lake Dead", Liverpool Daily Post, 6 November 1939, p. 4

- ↑ Manley, p. 124

- ↑ "No hope is left for Collins Music Hall", The Stage, 7 July 1994, p. 4

Sources

- Baker, Richard Anthony (2005). British Music Hall. Stroud: Sutton. OCLC 1335736003.

- Manley, Bill (1990). Islington Entertained. London: Islington Libraries. ISBN 978-0-90-226025-2.