Compulsory figures or school figures were formerly a segment of figure skating, and gave the sport its name. They are the "circular patterns which skaters trace on the ice to demonstrate skill in placing clean turns evenly on round circles".[1] For approximately the first 50 years of figure skating as a sport, until 1947, compulsory figures made up 60 percent of the total score at most competitions around the world. These figures continued to dominate the sport, although they steadily declined in importance, until the International Skating Union (ISU) voted to discontinue them as a part of competitions in 1990. Learning and training in compulsory figures instilled discipline and control; some in the figure skating community considered them necessary to teach skaters basic skills. Skaters would train for hours to learn and execute them well, and competing and judging figures would often take up to eight hours during competitions.

Skaters traced compulsory figures, and were judged according to their smoothness and accuracy. The circle is the basis of all figures. Other elements in compulsory figures include curves, change of foot, change of edge, and turns. Skaters had to trace precise circles while completing difficult turns and edges. The simple "figure eight" shape was executed by connecting two circles; other figures included the three turn, the counter turn, the rocker turn, the bracket turn, and the loop.

Since 2015 with the founding of the World Figure Sport Society and the World Figure & Fancy Skating Championships & Festival on black ice more skaters are training and competing in figures.[2] More coaches are learning the new methods developed by World Figure Sport to teach them to skaters, as some skaters and coaches believe that figures give skaters an advantage in developing alignment, core strength, body control, and discipline. The World Figure Sport Society conducts workshops,[3] festivals and world competitions in compulsory (now known as fundamental figures), special, creative, free, flying figures, and fancy skating[4]

History

Early history

Tracing figures in the ice is the oldest form of figure skating, especially during its first 200 years of existence when it was a recreational activity practiced mostly by men. Combined skating, or "patterns of moves for two skaters around a common center marked by a ball and later an orange placed on the ice",[5] had a "profound historical significance"[6] to the sport that eventually manifested itself in ice dancing, pair skating, and synchronized skating, and dominated the sport for 50 years in England during the 18th century.[6] The Art of Skating, one of the earliest books about figure skating, was written by Robert Jones in 1772 and described five advanced figures, three of which were illustrated with large color plates.[7] Jones' limited body of figures, which emphasized correct technique, were the accepted and basic repertoire of figures in 18th-century England.[8] The Edinburgh Skating Club, one of the oldest skating clubs in the world, described combined figures and those done by multiple skaters; interlocking figure eights were the most important.[9] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum, the Edinburgh Skating Club required prospective members to pass proficiency tests in what became compulsory figures.[10] The London Skating Club, founded in 1830 in London, also required proficiency tests for members and pioneered combined skating, which contributed to the evolution of school figures.[5] Artistic skating in France, which was derived from the English style of figure skating and was influenced by ballet, developed figures that emphasized artistry, body position, and grace of execution. Jean Garcin, a member of an elite group of skaters in France, wrote a book about figure skating in 1813 that included descriptions and illustrations of over 30 figures, including a series of circle-eight figures that skaters still use today.[11]

George Anderson, writing in 1852, described backward-skating figures, including the flying Mercury and the shamrock, as well as the Q figure, which became, in its various forms, an important part of the repertoire of skating movements for the rest of the 1800s. Anderson also described two combined figures, the salutation (already described by Jones) and the satellite. By the 1850s, the most important figures (eights, threes, and Qs) were developed and formed the basis for figure skating at the time.[12] In 1869, Henry Vandervell and T. Maxwell Witham from the London Skating Club wrote System of Figure Skating, which described variations of the three turn (the only figure known before 1860), the bracket (first done on roller skates), the rocker, the Mohawk, the loop, the Q, and other figures.[13] The Mohawk, renamed in Canada to the C Step in 2020, a two-foot turn on the same circle, most likely originated in North America.[14][15] Figure skating historian James Hines called grapevines, which was probably invented in Canada, "the most American of all figures".[16] The Viennese style of figure skating, as described by Max Wirth's book in 1881, described connecting figures, which ultimately led to modern free skating programs.[17]

In 1868, the American Skating Congress, precursor to U.S. Figure Skating, adopted a series of movements used during competitions between skaters from the U.S. and Canada. Until 1947, for approximately the first 50 years of the existence of figure skating as a sport, compulsory figures made up 60 percent of the total score at most competitions around the world.[18] Other competitions held in the late 19th and early 20th centuries included special figures, freeskating, and compulsories, most of the points they earned going towards how they performed the same set of compulsory moves.[19] The first international figure skating competition was in Vienna in 1882;[20][21] according to Kestnbaum, it established a precedent for future competitions.[22][23] Skaters were required to perform 23 compulsory figures, as well as a four-minute freeskating program, and a section called "special figures", in which they had to perform moves or combinations of moves that highlighted their advanced skills.[23]

Compulsory figures were an important part of figure skating for the rest of the 19th century until the 1930s and 1940s. The first European Championships in 1891 consisted of only compulsory figures.[24] In 1896, the newly formed International Skating Union (ISU) sponsored the first annual World Figure Skating Championships in St. Petersburg. The competition consisted of compulsory figures and free skating.[25] Skaters had to perform six compulsory moves so that judges could compare skaters according to an established standard. Compulsory figures were worth 60 percent of the competitors' total scores.[26]

Special figures were not included in World Championships, although they were included as a separate discipline in other competitions, including the Olympics in 1908.[26] The early Olympics movement valued and required amateurism, so figure skating, almost from its beginnings as an organized sport, was also associated with amateurism. Athletes were unable to support themselves financially, so as Kestnbaum put it, "thus making it impossible for those who had to earn a living by other means to attain the same level of skill as those who were independently wealthy or who practiced professions that allowed for flexible scheduling".[27] According to Kestnbaum, this had implications for attaining proficiency in complusory figures, which required long hours of practice and purchasing time at private rinks and clubs.[27]

In 1897, the ISU adopted a schedule of 41 school figures, each of increasing difficulty, which was proposed by the British. They remained the standard compulsory figures used throughout the world in proficiency testing and competitions until 1990, and U.S. Figure Skating continued to use them as a separate discipline in the 1990s. After World War II, more countries were sending skaters to international competitions, so the ISU cut the number of figures to a maximum of six due to the extended time it took to judge them all.[26][18]

Demise in 1990 and Modern Renaissance in 2015

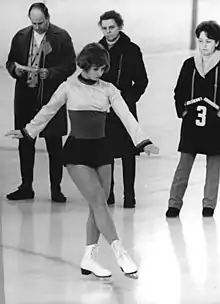

Compulsory figures began to be progressively devalued in 1967 when the values of both compulsory figures and free skating were changed to 50 percent.[28] In 1973, the number of figures was decreased from six to three, and their overall weight was decreased to 30 percent, to make room for the introduction of the short program.[18][29] Hines states that the decrease in the importance of compulsory figures was due to "the unbalanced skating"[30] of women skaters such as Beatrix "Trixi" Schuba of Austria, whom Hines called "the last great practitioner of compulsory figures".[30] Schuba won several medals in the late 1960s and early 1970s based upon the strength of her figures, despite her lower results in free skating. As Hines states, "she could not be defeated under a scoring system that gave preference to figures".[30] Hines also credited television coverage of figure skating, which helped to increase the popularity of the sport, with the eventual demise of compulsory figures. Television audiences were not exposed to the compulsory figures segments of competitions, so they did not understand why the results contradicted what they saw in free skating segments.[31] Sports writer Sandra Loosemore agreed, stating that television was "the driving force"[18] for the rule changes regarding figures in 1968 and the years following. Figures were not broadcast on television because they were not exciting enough, so viewers "found it incomprehensible that competitions could be won by skaters who had built up huge leads in the figures portion of the event but gave mediocre performances in the part of the competition shown on TV".[18] In 1973, the ISU lowered the value of compulsory figures from 50% to 40% and decreased the number of figures skaters were required to perform. In 1977, the number of types of figures skaters could choose to perform decreased even more, down to six figures per competition.[31]

Loosemore attributed the decrease in the importance of figures to a "lack of public accountability"[18] from the judges of international competitions and other discrepancies in judging, which Loosemore called "dirty judging".[18] She speculated that television coverage of the sport, which brought more attention to how it was judged, was also responsible and "since figures competitions weren't televised, fans could not be certain that the judges were on the level".[18] Loosemore also speculated that "the relative scarcity of rinks and practice ice for figures in Europe as compared to North America"[18] ultimately made the difference in the removal of figures from competitions. Kestnbaum agreed, stating that the elimination of figures was motivated by finances, countries with an affluent middle class or government-supported training for athletes having more of a competitive advantage over less affluent and smaller countries with fewer ice rinks and resources to spend the time necessary to train for proficiency in figures. By the late 1970s and into the 1980s, there were discussions about eliminating them from international competitions.[32]

In 1988, the ISU voted to remove compulsory figures from international single skating competitions, for both men and women, starting in the 1990–1991 season. Of 31 voting national associations, only the U.S., Canada, Britain, and New Zealand voted against the decision.[29] The last two seasons that compulsory figures were competed at an international competition were in 1989 and 1990; only two figures were skated and they were worth only 20 percent of the competitors' overall scores.[18][32] Željka Čižmešija from Yugoslavia skated the last compulsory figure in international competition, at the World Championships in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 7 March 1990.[33]

The U.S. created a separate track for figures instead of immediately eliminating them as most other countries did and was the last skating federation to include figures at its national championships, at the 1999 U.S. Figure Skating Championships. Its governing council, due to dwindling participation in figures since the ISU ended them in international competitions, finally voted to end them, even at the lower levels of its competitions and for their proficiency tests, in the summer of 1997. Canada also voted to end figures for their proficiency tests in 1997.[18] According to Loosemore, the U.S.' decision to replace the remaining figure proficiency test requirements for competition eligibility in the mid-1990s with moves in the field to test skating proficiency "killed figures as a separate competition discipline".[18] Sports writer Randy Harvey of the Los Angeles Times predicted that the free skate would become the focus in international competitions.[34] Hines, quoting Italian coach Carlo Fassi, predicted in 2006 that the elimination of figures would result in younger girls dominating the sport, a statement Hines called "prophetic".[35]

According to Loosemore, after figures were no longer required, most skaters stopped doing them, resulting in rinks cutting back on the amount of time they offered to skaters who wanted to continue to practice them and a reduction in the number of judges capable of scoring them.[18] Despite the apparent demise of compulsory figures from figure skating, coaches continued to teach figures and skaters continued to practice them because figures gave skaters an advantage in developing alignment, core strength, body control, and discipline.[36] Proponents stated that figures taught basic skating skills, insisting that if skaters did not become proficient in figures, they would not be able to perform well-done free skating programs.[37][34] American champion and figure skating writer John Misha Petkevich disagrees, stating that the skills needed for proficiency in figures were different than what was needed for free skating, and that the turns and edges learned in figures could be learned in free skating as easily and efficiently.[38]

A renaissance happened in figures when the World Figure Sport Society held the inaugural World Figure Championship & Festival on black ice in Lake Placid, New York, which was also endorsed by the Ice Skating Institute, in 2015.[39] The World Figure Sport Society brought the 2016 World Figure Championship on black ice to Toronto, Canada and has held continuous World Figure & Fancy Skating[40] Championships & Festivals on black ice[41] in the following locations: 2017–2019 in Vail, Colorado, 2020 in Plattsburgh,[42] New York, and in Brasher Falls, New York in 2021 and 2022. Many figure and fancy skating compositions are competed with sequestered judging to avoid bias. Skating artists compete many types of figures including fundamental (previously known as compulsory or school), special,[3] creative, free, and flying figures which when combined creates fancy skating[40] to music.

Execution of figures

Compulsory figures, also called school figures, are the "circular patterns which skaters trace on the ice to demonstrate skill in placing clean turns evenly on round circles".[1][lower-alpha 1] Compulsory figures are also called "patch", a reference to the patch of ice allocated to each skater to practice figures.[36] Figure skating historian James Hines reports that compulsory figures were "viewed as a means of developing technique necessary for eliter skaters".[43] He states, "As scales are the material by which musicians develop the facile technique required to perform major competitions, so compulsory figures were viewed as the material by which skaters develop the facile required for free-skating programs".[43] Hines also states that although compulsory figures and free skating are often considered as "totally different aspects of figure skating", historically they were not, and insisted that "spirals, spread eagles, jumps, and spins were originally individual figures".[44]

Skaters were required to trace these circles using one foot at a time, demonstrating their mastery of control, balance, flow, and edge to execute accurate and clean tracings on the ice.[1] The compulsory figures used by the International Skating Union (ISU) in 1897 for international competitions consisted of "two or three tangent circles with one, one and a half, or two full circles skated on each foot, in some with turns or loops included on the circles".[26] The patterns skaters left on the ice, rather than the shapes the body made executing them, became the focus of artistic expression in figure skating into the 20th century.[45] The quality of the figures, along with the skater's form, carriage, and speech in which they were executed, was emphasized, not the intricacy of unique designs of the figures themselves.[43]

The highest quality figures had tracings on top of each other; their edges were placed precisely, and the turns lined up exactly. The slightest misalignment or shift of body weight could cause errors in the execution of figures.[36] American figure skating champion Irving Brokaw insisted that form was more essential to the production of figures than the tracings themselves because the skater needed to find a comfortable and natural position in which to perform them.[46] He expected skaters to trace figures without looking down at them because it gave "a very slovenly appearance",[46] and recommended that they not use their arms excessively or for balance like tightrope walkers. Brokaw wanted skaters to remain upright and avoid bending over as much as they could. Brokaw also thought that the unemployed leg, which he called the "balance leg", was as important as the tracing leg because it was used as much in the execution of a figure as the tracing leg. The balance leg also should be bent only slightly, since he believed bending it too much removed its usefulness and appeared clumsy.[47]

Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum notes that skaters who were adept at performing compulsory figures had to practice for hours to have precise body control and to become "intimately familiar with how subtle shifts in the body's balance over the blade affected the tracings left on the ice".[27] She adds that many skaters found figures and their visible results calming and rewarding.[37] Sports writer Christie Sausa insists that training in figures "helps create better skaters and instills discipline, and can be practiced over a lifetime by skaters of all ages and abilities".[36] The German magazine Der Spiegel declared in 1983 that compulsory figures stifled skaters' creativity because not much about figures had changed in 100 years of competitions.[48]

Figure elements

All compulsory figures had the following: circles, curves, change of foot, change of edge, and turns. The circle, the basis of all figures, was performed on both its long and short axes. Skaters had to trace precise circles, while completing difficult turns and edges.[36][49] Most figures employ "specific one-foot turns not done in combination with other one-foot turns".[43] Each figure consisted of two or three tangent circles. Each circle's diameter had to be about three times the skater's height,[lower-alpha 2] and the radii of all half-circles had to be approximately the same length. Half-circles and circles had to begin and end as near as possible to the point in which the long and short axes intersected. The figure's long axis divided it longitudinally into equal-sized halves, and the figure's short axes divided the figures into equal-sized lobes.[50]

Curves, which are parts of circles, had to be performed with an uninterrupted tracing and with a single clean edge, with no subcurves or wobbles.[51] Brokaw insists that curves had to be done on all four edges of the skate while skating both backwards and forwards.[52] He states, "It is the control of these circles that gives strength and power, and the holding of the body in the proper and graceful attitudes, while it is the execution of these large circles, changes of edges, threes and double-threes, brackets, loops, rockers and counters, which makes up the art of skating".[52] Curves also included the forced turn (or bracket) and the serpentine.[52]

A change of foot, which happened during the short time the skater transferred weight from one foot to the other, was allowed in the execution of figures, but had to be done in a symmetrical zone on each side of the long axis. Skaters could choose the exact point in which they placed their foot in this zone, although it typically was just after the long axis, with the full weight of the body on the skate. It was at this point that tracing began.[50] A change of edge happened at the point in which the long and short axes intersected. Its trace had to be continuously and symmetrically traced and could not be S-shaped. The edge change had to be as short as possible, and could not be longer than the length of the skate blade.[lower-alpha 3] Turns were skated with a single clean edge up to and after the turn, but with no double tracings, no skids or scrapes, or no illegal edge change either before, during, or after a turn. The turns' cusps had to be the same size, and the entry into and out of a turn had to be symmetrical.[51]

The simple "figure eight" shape was executed by connecting two circles "about three times the height of the skater[lower-alpha 4] with one circle skated on each foot".[18] The figure eight has four variations: inside edges, outside edges, backward, and forward. A turn added at the halfway point of each circle increased the level of complexity. Other figures included three-lobed figures with a counter turn or a rocker turn, which were completed at the points where the lobes touched.[18] Counters and rockers had to be executed symmetrically, with no change of edge, with the points of their turns either pointing up or down or lying along the figure's long axis, and could not be beaked or hooked. Brackets, like threes, had to be skated on a circle, their turns' points either pointing up or down or lying along the figure's long axis.[51]

Skaters also performed a group of smaller figures called loops.[18] The diameter of the loop's circular shape had to be about the height of the skater, and they could not have any scrapes or points on the ice. The place in which the skater entered into or exited out of the crossing of both the loop tracing and the center of the loop had to sit on the figure's long axis, where the loop was divided into symmetrical halves. The center of the loop figure to the place in which the skater entered into or exited out of the loop's crossing had to measure five-sixths of the circle's diameter. The loop's length had to be about one-third of the distance from the place in which the skater entered into or exited out of the loop's crossing of the loop tracing to the figure's short axis. The loop's width had to be about two-thirds of its length.[51] The Q figure begins at the tail of the figure, on the skater's outside edge. It can also begin on any of the four edges, and the direction in which it can be skated can be reversed. When the circle is skated first, it is called a reverse Q.[14] Altered forms of the Q figure often do not look like the letter "q", but "simply employ a serpentine line and a three turn".[14] United shamrocks, spectacles (shapes that trace the shape of eyeglasses), and united roses are alterations of the basic Q figures.[14]

Since the goal of figures is drawing an exact shape on the ice, the skater had to concentrate on the depth of the turn (how much the turn extends into or out of the circle), the integrity of the edges and cusps (round-patterned edges leading into or out of the circle), and its shape.[53] There were three types of three turns: the standard three, the double three, and the paragraph double three. The three turn had to be skated on a circle, its turns' points either pointing up or down or lying along the figure's long axis.[18][51] For the double three, the points of both threes had to be directed towards the center of each circle, and had to divide the circle into three equal curves. The middle curve had to divide the circles into halves by the figure's long axis.[51] The paragraph double three, which was executed at the highest levels of competition, was done by tracing "two circles with two turns at each circle, all on one foot from one push-off".[18] The paragraph double three was difficult to accomplish because the shape and placement of the turns had to be perfectly symmetrical, the turns had to be done on a true edge with no scrapes on the ice, and the circles had to be the same size and exactly round.[18] All combined compulsory figures are illustrated below:

The figure-eight

The figure-eight- The 3 turn

- The counter turn

The rocker turn

The rocker turn- The bracket turn

The loop

The loop

Judging

Der Spiegel compared judging compulsory figures to the work of forensic scientists.[48] After the skaters completed tracing figures, the judges scrutinized the circles made, and the process was repeated twice more. According to Randy Harvey, compulsory figures took five hours to complete at U.S. National Championships and eight hours at World Championships.[34] At the 1983 European Championships, the compulsory segment began at 8 am, and lasted six hours.[48]

The ISU published a judges' handbook describing what judges needed to look for during compulsory figure competitions in 1961.[54] Skaters were judged on the ease and flow of their movement around the circles, the accuracy of the shapes of their bodies, and the accuracy of the prints traced on the ice. Judges took note of the following: scrapes, double tracks that indicated that both edges of their blades were in contact with the ice simultaneously, deviations from a perfect circle, how closely the tracings from each repetition followed each other, how well the loops lined up, and other errors.[26]

In 2015, a new era of judging figures was ushered in with the founding of the World Figure Sport Society.[55] World Figure Sport created sequestered judging to avoid judging bias which easily occurred in previous times. Skating artists are now judged at the World Figure & Fancy Skating Championships on black ice by judges ranking all the figure compositions that are skated and etched into the ice.[2] Judges only enter the ice after the competitors leave and rank the technically strongest to weakest figure compositions. This new era has produced the most iconic images and videos of the figure patterns of all types being performed and competed in world competition in the history of figure skating.

Notes

- ↑ See the historical document "Special Regulations for Figures" for an example of past competition rules and regulations for figures. See especially diagrams of figures, pp. 12–21.

- ↑ 5 to 7 metres (16 ft 5 in to 23 ft 0 in)

- ↑ 30 to 40 centimetres (12 to 16 in)

- ↑ 5 to 7 metres (16 ft 5 in to 23 ft 0 in)

References

- 1 2 3 Special Regs, p. 1

- 1 2 Radnofsky, Louise. "Who Needs Triple Axels and Toe Loops—Give Us 'Compulsory Figures'". WSJ. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- 1 2 "World figure skating enthusiasts take figures online | News, Sports, Jobs - Lake Placid News". Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ↑ Meagher, George A. (1895). Figure and Fancy Skating. Bliss, Sands, and Foster. ISBN 978-0-598-48290-7.

- 1 2 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 60.

- 1 2 Hines 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Hines 2006, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Hines 2006, pp. 27, 62.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Hines 2006, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 30–31.

- ↑ Hines 2006, pp. 31, 32–34.

- 1 2 3 4 Hines 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ "Terminology Change". Skate Canada. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 59.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Loosemore, Sandra (16 December 1998). "'Figures' Don't Add up in Competition Anymore". CBS SportsLine. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ Kestnbaum 2003, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ "History". International Skating Union. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ Hines 2011, p. xx.

- ↑ Kestnbaum, p. 67

- 1 2 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Hines 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 73.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 197.

- 1 2 "No More Figures in Figure Skating". The New York Times. Associated Press. 9 June 1988. p. D00025. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 Hines 2006, p. 204.

- 1 2 Hines 2006, p. 205.

- 1 2 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 86.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 235.

- 1 2 3 Harvey, Randy (8 January 1988). "It's Compulsory, but Is It Necessary?: For Now, Tedious Competition Counts; Debi Thomas Takes Lead". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ↑ Hines 2006, pp. 235–236.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sausa, Christie (1 September 2015). "Figures Revival". Lake Placid News. Lake Placid, New York. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- 1 2 Kestnbaum 2003, p. 84.

- ↑ Petkevich 1988, p. 21.

- ↑ "World Figure Championship & Figure Festival coming to Lake Placid, NY" (Press release). Lake Placid, N.Y.: World Figure Sport Society. 25 April 2015. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- 1 2 Meagher, George A. (1895). Figure and Fancy Skating. Bliss, Sands, and Foster. ISBN 978-0-598-48290-7.

- ↑ Lafranca, Joey (2 January 2021). "COOL AS ICE: World Figure & Fancy Skating Championships thrive in Plattsburgh". Press-Republican. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ↑ Lafranca, Joey (2 January 2021). "Competitors carve out their talents at skating championships". Press-Republican. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Hines 2006, p. 99.

- ↑ Hines 2006, p. 100.

- ↑ Kestnbaum 2003, p. 59.

- 1 2 Brokaw 1915, p. 19.

- ↑ Brokaw 1915, pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 3 "Eiskunstlauf: Das Schlimmste". Der Spiegel (in German). 7 February 1983. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ↑ Special Regs, pp. 2-3

- 1 2 Special Regs, p. 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Special Regs, p. 3

- 1 2 3 Brokaw 1915, p. 23.

- ↑ Petkevich 1988, p. 85.

- ↑ Hines 2011, p. xxv.

- ↑ "Figures revival | News, Sports, Jobs - Lake Placid News". Retrieved 5 February 2023.

Works cited

- Brokaw, Irving (1915). The Art of Skating. New York: American Sports Publishing Company. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Hines, James R. (2006). Figure Skating: A History. Urbana, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-252-07286-3.

- Hines, James R. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6859-5.

- Kestnbaum, Ellyn (2003). Culture on Ice: Figure Skating and Cultural Meaning. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0819566416.

- Petkevich, John Misha (1988). Sports Illustrated Figure Skating: Championship Techniques (1st ed.). New York: Sports Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-4616-6440-6. OCLC 815289537. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- Special Regulations for Figures (Special Regs). U.S. Figure Skating Association. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Meagher, George A. (1895). Figure and Fancy Skating. Bliss, Sands, and Foster. ISBN 978-0-598-48290-7