In linguistics, control is a construction in which the understood subject of a given predicate is determined by some expression in context. Stereotypical instances of control involve verbs. A superordinate verb "controls" the arguments of a subordinate, nonfinite verb. Control was intensively studied in the government and binding framework in the 1980s, and much of the terminology from that era is still used today.[1] In the days of Transformational Grammar, control phenomena were discussed in terms of Equi-NP deletion.[2] Control is often analyzed in terms of a null pronoun called PRO. Control is also related to raising, although there are important differences between control and raising. Most if not all languages have control constructions and these constructions tend to occur frequently.

Examples

Standard instances of (obligatory) control are present in the following sentences:

- Susan promised to help us. - Subject control with the obligatory control predicate promise

- Fred stopped laughing. - Subject control with the obligatory control predicate stop

- We tried to leave. - Subject control with the obligatory control predicate try

- Sue asked Bill to stop. - Object control with the obligatory control predicate ask

- They told you to support the effort. - Object control with the obligatory control predicate tell

- Someone forced him to do it. - Object control with the obligatory control predicate force

Each of these sentences contains two verbal predicates. Each time the control verb is on the left, and the verb whose arguments are controlled is on the right. The control verb determines which expression is interpreted as the subject of the verb on the right. The first three sentences are examples of subject control, since the subject of the control verb is also the understood subject of the subordinate verb. The second three examples are instances of object control, because the object of the control verb is understood as the subject of the subordinate verb. The argument of the matrix predicate that functions as the subject of the embedded predicate is the controller. The controllers are in bold in the examples.

Control verbs vs. auxiliary verbs

Control verbs have semantic content; they semantically select their arguments, that is, their appearance strongly influences the nature of the arguments they take.[3] In this regard, they are very different from auxiliary verbs, which lack semantic content and do not semantically select arguments. Compare the following pairs of sentences:

- a. Sam will go. - will is an auxiliary verb.

- b. Sam yearns to go. - yearns is a subject control verb.

- a. Jim has to do it. - has to is a modal auxiliary verb.

- b. Jim refuses to do it. - refuses is a subject control verb.

- a. Jill would lie and cheat. - would is a modal auxiliary.

- b. Jill attempted to lie and cheat. - attempted is a subject control verb.

The a-sentences contain auxiliary verbs that do not select the subject argument. What this means is that the embedded verbs go, do, and lie and cheat are responsible for semantically selecting the subject argument. The point is that while control verbs may have the same outward appearance as auxiliary verbs, the two verb types are quite different.

Non-obligatory or optional control

Control verbs (such as promise, stop, try, ask, tell, force, yearn, refuse, attempt) obligatorily induce a control construction. That is, when control verbs appear, they inherently determine which of their arguments controls the embedded predicate. Control is hence obligatorily present with these verbs. In contrast, the arguments of many verbs can be controlled even when a superordinate control verb is absent, e.g.

- He left, singing all the way. - Non-obligatory control of the present participle singing

- Understanding nothing, the class protested. - Non-obligatory control of the present participle understanding

- Holding his breath too long, Fred passed out. - Non-obligatory control of the present participle holding

In one sense, control is obligatory in these sentences because the arguments of the present participles singing, understanding, and holding are clearly controlled by the matrix subjects. In another sense, however, control is non-obligatory (or optional) because there is no control predicate present that necessitates that control occur.[4] General contextual factors are determining which expression is understood as the controller. The controller is the subject in these sentences because the subject establishes point of view.

Some researchers have begun to use the term "obligatory control" to just mean that there is a grammatical dependency between the controlled subject and its controller, even if that dependency is not strictly required. "Non-obligatory control", on the other hand, may be used just to mean that there is no grammatical dependency involved.[5] Both "obligatory control" and "non-obligatory control" can be present in a single sentence. The following example can either mean that the pool had been in the hot sun all day (so it was nice and warm), in which case there would be a syntactic dependency between "the pool" and "being". Or it can mean that the speaker was in the hot sun all day (so the pool is nice and cool), in which case there would be no grammatical dependency between "being" and the understood controller (the speaker).[6] In such non-obligatory control sentences, it appears that the understood controller needs to be either a perspective holder in the discourse or an established topic.[7]

The pool was the perfect temperature after being in the hot sun all day.

Arbitrary control

Arbitrary control occurs when the controller is understood to be anybody in general, e.g.[8]

- Reading the Dead Sea Scrolls is fun. - Arbitrary control of the gerund reading.

- Seeing is believing. - Arbitrary control of the gerunds seeing and believing

- Having to do something repeatedly is boring. - Arbitrary control of the gerund having

The understood subject of the gerunds in these sentence is non-discriminate; any generic person will do. In such cases, control is said to be "arbitrary". Any time the understood subject of a given predicate is not present in the linguistic or situational context, a generic subject (e.g. 'one') is understood.

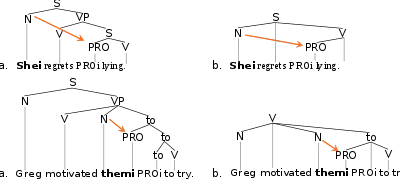

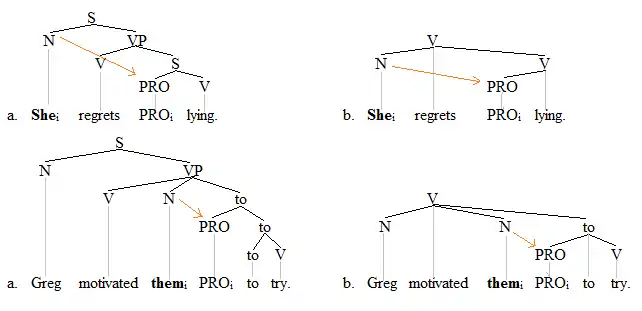

Representing control

Theoretical linguistics posits the existence of the null pronoun PRO as the theoretical basis for the analysis of control structures. The null pronoun PRO is an element that impacts a sentence in a similar manner to how a normal pronoun impacts a sentence, but the null pronoun is inaudible.[9] The null PRO is added to the predicate, where it occupies the position that one would typically associate with an overt subject (if one were present). The following trees illustrate PRO in both constituency-based structures of phrase structure grammars and dependency-based structures of dependency grammars:[10]

The constituency-based trees are the a-trees on the left, and the dependency-based trees the b-trees on the right. Certainly aspects of these trees - especially of the constituency trees - can be disputed. In the current context, the trees are intended merely to suggest by way of illustration how control and PRO are conceived of. The indices are a common means of identifying PRO and with its antecedent in the control predicate, and the orange arrows indicate further the control relation. In a sense, the controller assigns its index to PRO, which identifies the argument that is understood as the subject of the subordinate predicate.

A (constituency-based) X-bar theoretic tree that is consistent with the standard GB-type analysis is given next:[11]

The details of this tree are, again, not so important. What is important is that by positing the existence of the null subject PRO, the theoretical analysis of control constructions gains a useful tool that can help uncover important traits of control constructions.

Control vs. raising

Control must be distinguished from raising, though the two can be outwardly similar.[12] Control predicates semantically select their arguments, as stated above. Raising predicates, in contrast, do not semantically select (at least) one of their dependents. The contrast is evident with the so-called raising-to-object verbs (=ECM-verbs) such as believe, expect, want, and prove. Compare the following a- and b-sentences:

- a. Fred asked you to read it. - asked is an object control verb.

- b. Fred expects you to read it. - expects is a raising-to-object verb.

- a. Jim forced her to say it. - forced is an object control verb.

- b. Jim believed her to have said it. - believes is a raising-to-object verb.

The control predicates ask and force semantically select their object arguments, whereas the raising-to-object verbs do not. Instead, the object of the raising verb appears to have "risen" from the subject position of the embedded predicate, in this case from the embedded predicates to read and to have said. In other words, the embedded predicate is semantically selecting the argument of the matrix predicate. What this means is that while a raising-to-object verb takes an object dependent, that dependent is not a semantic argument of that raising verb. The distinction becomes apparent when one considers that a control predicate like ask requires its object to be an animate entity, whereas a raising-to-object predicate like expects places no semantic limitations on its object dependent.

Diagnostic Tests

Expletives

The different predicate types can be identified using expletive there.[13] Expletive there can appear as the "object" of a raising-to-object predicate, but not of a control verb, e.g.

- a. *Fred asked there to be a party. - Expletive there cannot appear as the object of a control predicate.

- b. Fred expects there to be a party. - Expletive there can appear as the object of a raising-to-object predicate.

- a. *Jim forced there to be a party. - Expletive there cannot appear as the object of a control predicate.

- b. Jim believes there to have been a party. - Expletive there can appear as the object of a raising-to-object predicate.

The control predicates cannot take expletive there because there does not fulfill the semantic requirements of the control predicates. Since the raising-to-object predicates do not select their objects, they can easily take expletive there.

Idioms

Control and raising also differ in how they behave with idiomatic expressions.[14] Idiomatic expressions retain their meaning in a raising construction, but they lose it when they are arguments of a control verb. See the examples below featuring the idiom "The cat is out of the bag", which has the meaning that facts that were previously hidden are now revealed.

- a. The cat wants to be out of the bag. - There is no possible idiomatic interpretation in the control construction.

- b. The cat seems to be out of the bag. - The idiomatic interpretation is retained in the raising construction.

The explanation for this fact is that raising predicates do not semantically select their arguments, and therefore their arguments are not interpreted compositionally, as the subject or object of the raising predicate. Arguments of the control predicate, on the other hand, have to fulfill their semantic requirements, and interpreted as the argument of the predicate compositionally.

This test works for object control and ECM too.

- a. I asked the cat to be out of the bag. - There is no possible idiomatic interpretation in the control construction.

- b. I believe the cat to be out of the bag. - The idiomatic interpretation is retained in the raising construction.

Notes

- ↑ See for instance van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:128ff.), Cowper (1992:161ff.), Borsley (1996:126-144).

- ↑ Concerning the designation Equi-NP deletion for control structures, see for instance Bach (1974:116f.), Emonds (1976:193f. note 15), Culicover (1982:250).

- ↑ Accounts of control emphasize that control verbs semantically select their dependents, as opposed to raising predicates, which do not select one of their dependents. See for instance van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:130), Borsley (1996:133), Culicover (1997:102).

- ↑ See van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:137) and Haegeman (1994:277) concerning non-obligatory/optional control.

- ↑ Landau, Idan (2015-05-01). A Two-Tiered Theory of Control. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52736-1.

- ↑ Green, Jeffrey J. (2019-07-31). "A movement theory of adjunct control". Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics. 4 (1). doi:10.5334/gjgl.724. ISSN 2397-1835.

- ↑ Landau, Idan (2021-10-19). A Selectional Theory of Adjunct Control. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54285-2.

- ↑ Arbitrary control is discussed for instance by van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:137f.), Cowper 1992:162), Culicover (1997:75-76), Carnie (207:285ff.).

- ↑ For accounts of PRO, see for instance van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:132ff.), Cowper (1992:157ff.), Haegeman (1994:257ff.), Culicover (1997:75-77), Carnie (2007:395ff.).

- ↑ The constituency trees shown here are similar to those that were widely produced in the 1970s, e.g. Bach (1974). The dependency trees here are similar to those that are produced by Osborne and Groß (2012).

- ↑ Numerous GB trees like the one here can be found in, for instance, Haegeman (1994).

- ↑ Concerning the difference between control and raising, see Bach (1974:149), Culicover (1997:102), Carnie (2007:403ff.).

- ↑ The expletive is widely employed to distinguish control from raising constructions. See for instance Grinder and Elgin (1973:142-143), Bach (1973:151), McCawley (1988:121), Borsley (1996:127), Culicover (1997:102), Saito (1999:8-9).

- ↑ Many syntax books discuss the way idioms are used to diagnose control and raising constructions. See Carnie (2007), Davies & Dubinsky (2008).

See also

References

- Bach, E. 1974. Syntactic theory. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.

- Borsley, R. 1996. Modern phrase structure grammar. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Carnie, A. 2007. Syntax: A generative introduction, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Cowper, E. 2009. A concise introduction to syntactic theory: The government-binding approach. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Culicover, P. 1982. Syntax, 2nd edition. New York: Academic Press.

- Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and Parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford University Press.

- Davies, William D., and Stanley Dubinsky. 2008. The grammar of raising and control: A course in syntactic argumentation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Emonds, J. 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax: Root, structure-preserving, and local transformations. New York: Academic Press.

- Grinder, J. and S. Elgin. 1973. Guide to transformational grammar: History, theory, and practice. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc.

- Haegeman, L. 1994. Introduction to government and binding theory, 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Lasnik, H. and M. Saito. 1999. On the subject of infinitives. In H. Lasnik, Minimalist analysis, 7-24. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- McCawley, T. 1988. The syntactic phenomena of English, Vol. 1. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163-214.

- van Riemsdijk, H. and E. Williams. 1986. Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Rosenbaum, Peter. 1967. The grammar of English predicate complement constructions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.