| Cookham | |

|---|---|

| Village and civil parish | |

Holy Trinity parish church | |

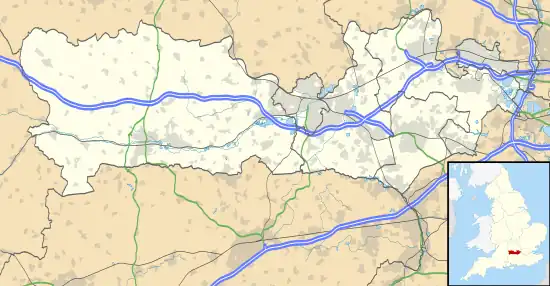

Cookham Location within Berkshire | |

| Population | 5,779 United Kingdom Census 2011[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU895855 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Maidenhead |

| Postcode district | SL6 |

| Dialling code | 01628 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Royal Berkshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

Cookham is a historic Thames-side village and civil parish on the north-eastern edge of Berkshire, England, 2.9 miles (5 km) north-north-east of Maidenhead and opposite the village of Bourne End. Cookham forms the southernmost and most rural part of the High Wycombe urban area. With adjoining Cookham Rise and Cookham Dean, it had a combined population of 5,779 at the 2011 Census.[1] In 2011, The Daily Telegraph deemed Cookham Britain's second richest village.[2]

Toponymy

It is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Cocheham. The name may be from the Old English cōc + hām, meaning 'cook village', i.e. 'village noted for its cooks', although the first element may be derived from the Old English cōc(e) meaning 'hill'.[3]

Geography

The parish includes three settlements:

- Cookham Village – the centre of the original village, with a high street that has changed little over the centuries

- Cookham Dean – the most rural village in the parish

- Cookham Rise – the middle area that grew up round the railway station

The ancient parish of Cookham covered all of Maidenhead north of the Bath Road until this was severed in 1894, including the hamlets of Furze Platt and Pinkneys Green.[4] There were several manors: Cookham, Lullebrook, Elington, Pinkneys, Great Bradley, Bullocks, White Place and Cannon Court. The neighbouring communities are Maidenhead to the south, Bourne End to the north, Marlow and Bisham to the west and Taplow to the east.

The River Thames flows past Cookham on its way between Marlow and Taplow. Several Thames islands belong to Cookham, such as Odney Island, Formosa Island and Sashes Island, which separates Cookham Lock from Hedsor Water. The Lulle Brook and the White Brook are tributaries of the Thames that flow through the parish. Much common land remains in the parish, such as Widbrook Common, Cookham Dean Common and Cock Marsh. Winter Hill affords views over the Thames Valley and Chiltern Hills. Cock Marsh is a site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) just to the north of the village.[5]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The area has been inhabited for thousands of years. Several prehistoric burial mounds on Cock Marsh were excavated in the 19th century and the largest stone axe ever found in Britain was one of 10,000 that has been dug up in nearby Furze Platt. The Roman road called the Camlet Way is reckoned to have crossed the Thames at Sashes Island, now cut by Cookham Lock, on its way from St. Albans to Silchester.[8] By the 8th century there was an Anglo-Saxon abbey in Cookham, under the patronage of the Kingdom of Mercia, and one of the later abbesses was Cynethryth, widow of Offa of Mercia. It became the centre of a power struggle between Mercia and Wessex, with the Thames forming a boundary between the two. In 2021 archaeological excavations by a team from the University of Reading discovered the site of the abbey, adjacent to Cookham's parish church, and items associated with it, while the following year additional excavations revealed extensive ancient infrastructure suggesting a larger settlement and trading centre.[9][10] Later, Alfred the Great made Sashes Island one of his burhs to help defend against Viking invaders. There was a royal palace here[11] where the Witan met in 997.

Although the earliest stone church building may have existed from 750, the earliest identifiable part of the current Holy Trinity parish church is the Lady Chapel, built in the late 12th century on the site of the cell of a female anchorite who lived next to the church and was paid a halfpenny a day by Henry II.[12]

In the Middle Ages, most of Cookham was owned by Cirencester Abbey and the timber-framed Churchgate House was apparently the Abbot's residence when in town. The Tarry Stone – still to be seen on the boundary wall of the Dower House – marked the extent of their lands. In 1611 the estate at Cookham was the subject of the first ever country house poem, Emilia Lanier's "Description of Cookham", which pays tribute to her patroness, Margaret Clifford through a description of her residence as a paradise for literary women. The estate at Cookham did not belong to Margaret, but was rented for her by her brother while she was undergoing a dispute with her husband.

%252C_Our_Village_(Cookham)%252C_1873.jpg.webp)

The townspeople resisted many attempts to enclose parts of the common land, including those by the Rev. Thomas Whateley in 1799, Miss Isabella Fleming in 1869, who wanted to stop nude bathing at Odney, and the Odney Estates in 1928, which wanted to enclose Odney Common.[13] The Maidenhead and Cookham Commons Preservation Committee was formed and raised £2,738 to buy the manorial rights and the commons which were then donated to the National Trust by 1937. These included Widbrook, Cock Marsh, Winter Hill, Cookham Dean Commons, Pinkneys Green Common and Maidenhead Thicket.[14]

Religion

Holy Trinity parish church is a Grade II* listed building containing several monuments, including a Purbeck marble table tomb with a vaulted canopy, supported by twisted columns, for Robert Peeke, clerk of the spicery to Henry VI, and his wife, (died 1517); a tablet with small kneeling figures in white relief by Flaxman, to mariner Sir Isaac Pocock, uncle of dramatist Isaac Pocock, who drowned in the Thames in 1810; and an elaborate mural tablet with kneeling figures to Arthur Babham (died 1560), surmounted by an entablature, crowned by a shield of his arms.[15]

Cookham Wesleyan Methodist chapel was built in 1846 and extended in 1911. It now houses the Stanley Spencer Gallery. The building was described as a Wesleyan chapel on a map of 1897–1899, but the label had gone by 1910–1912. This suggests that the reference to a 1911 extension is incorrect. In 1923–1925 it was simply described as a hall. It seems likely that it was closed with the construction of a new chapel at Cookham Rise in 1904.[16]

Economy

Cookham is home to the Chartered Institute of Marketing, based in Moor Hall. The John Lewis Partnership, operator of John Lewis department stores and Waitrose supermarkets, has a subsidised hotel and conference centre based at Odney for partners and their guests. The Partnership has four other subsidised hotels, at Ambleside (Lake District), Bala (north Wales), Brownsea Island (Poole Harbour) and Leckford (Hampshire).

Governance

Cookham's municipal services are provided by the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead and forms part of the Bisham and Cookham ward. Since May 2019 the village has two borough councillors, Mandy Brar (Lib Dem) and Gerry Clark (Conservative). Cookham also has a parish council with 15 councillors in three wards, Cookham (2 councillors), Cookham Rise (9 councillors) and Cookham Dean (4 councillors). Since May 2019 there have been four Conservative, nine Lib Dems and two independent councillors. The Council has a part-time Parish Clerk, and Assistant Clerk.[17] The local health services are managed by the East Berkshire PCT (primary care trust) – NHS Services.

Cookham is in the Maidenhead parliamentary constituency, the seat has been held since its creation in 1997 by Theresa May (Conservative).

Transport

Cookham village is on the A4094 between Maidenhead and Bourne End. The A404 from Maidenhead to High Wycombe is just to the west of Cookham Dean. Cookham railway station, at Cookham Rise, is on the Marlow branch line. There are half-hourly services to Maidenhead and Bourne End, with peak services extended to Marlow. An hourly bus service to Maidenhead, Bourne End and High Wycombe is provided by Arriva Shires & Essex six days a week. The river Thames has a long stretch of moorings above Cookham Bridge.

Attractions

The village as a tourist destination is a convenient base for walks along the Thames Path and across National Trust property. There is a selection of restaurants and pubs in the High Street. The Stanley Spencer Gallery, based in the former Methodist chapel, has a permanent exhibition of the artist's works.[18]

Arts and literature

- Kenneth Grahame is said to have been inspired by the River Thames at Cookham to write The Wind in the Willows, as he lived at The Mount in Cookham Dean as a child and returned to the village to write the book. Quarry Wood in Bisham, adjoining, is said to have been the original Wild Wood.

- The English painter Stanley Spencer was born here and most of his works depict villagers and their life in Cookham. His religious paintings usually had Cookham as a backdrop and a number of the landmarks in his canvases can still be seen in the village. Several of his works can be seen in the gallery in the centre of the village, close to where he lived. He also painted frescoes in at least one of the private houses in Cookham; however, they are not open to public viewing. His ashes are buried in the churchyard in the village.

- In Noël Coward's play Hay Fever, retired actress Judith Bliss and her family live in Cookham.

- Cookham is mentioned in Harold Pinter's short play Victoria Station which premiered at the Royal National Theatre with Paul Rogers and Martin Jarvis.

Notable residents

- Simon Aleyn (died 1565), supposed Singing Vicar of Bray

- Maidie Andrews (1893–1986), actress and singer, lived here for some years

- Chris Barrie (born 1960), actor, comedian and impressionist

- William Battie (died 1776), editor of Isocrates and founder of the University Scholarship at Cambridge

- Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland (1560–1616), to whom tribute paid in Emilia Lanier's 1611 country house poem "Description of Cookham"

- Henry Dodwell (1641–1711), scholar and theologian

- Benjamin Ferrers (1667–1732), deaf portraitist, whose family held the local lord of the manor of Lullebrook (or Cookham) for about 70 years

- Jessica Brown Findlay, actress, grew up in Cookham. Her maternal family come from the area.

- Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978), painter and the life partner of Patricia Preece

- Nathaniel Hooke (died 1763), historian

- Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932), writer

- Ulrika Jonsson (b. 1967) television presenter – lived in Cookham Dean for 21 years until 2011[19][20]

- Timmy Mallett (b. 1955), TV presenter, broadcaster and artist

- Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937), wireless pioneer, lived on Whyteladyes Lane and is said to have conducted experimental transmissions from there in 1897.

- Isaac Pocock (1782–1835), artist and dramatist buried in Cookham

- Patricia Preece (1894–1966), artist associated with the Bloomsbury Group and the second wife of Stanley Spencer

- Henry Thomas Ryall (1811–1867), engraver

- Frank Sherwin (1896–1986), railway poster artist

- Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), artist

- Ralph Thompson (1913–2009), animal artist and illustrator

- Frederick Walker (1840–1875), ARA

- Admiral Sir George Young, proposer of the settlement of New South Wales[21]

Town twinning

Cookham is twinned with:

Saint-Benoît, Vienne, a village near Poitiers, France.[22]

Saint-Benoît, Vienne, a village near Poitiers, France.[22]

Trivia

- In 2002 Cookham was at the centre of a row over the Department for Work and Pensions' description of the village's social profile as "somewhat spoiled by the gin and Jag brigade".[23]

- In 1997, 1999 and 2006 Cookham had its own radio station, Cookham Summer FM, that broadcast from Cookham railway station's waiting room and included a large number of Cookham residents.[24]

Notes

- 1 2 "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ "Britain's richest villages". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ Mills, AD (1991). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 90.

- ↑ Berkshire Records Office. "Cookham".

- ↑ "Magic Map Application". Magic.defra.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ Williams, David (10 May 2011). "Finds record for: SUR-910C71". The Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ Williams, David (13 May 2011) [10 May 2011]. "Finds record for: SUR-90A287". The Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ "Saxon Defence, Sashes and Cookham Area - Attachment A". Minas Tirith Archaeological Survey. 17 April 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ↑ "Archaeologists discover Mercian monastery from Anglo-Saxon period". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 19 August 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ↑ "Anglo-Saxon monastery was important trade hub - University of Reading". www.reading.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Ford, David Nash (2001). "Cookham". Royal Berkshire History.

- ↑ "The Cookhams". Archived from the original on 11 May 2010.

- ↑ Bootle, Robin; Bootle, Valerie (1990). The Story of Cookham. Cookham: published privately. ISBN 0-9516276-0-0.

- ↑ "Explore Maidenhead and Cookham Commons" (PDF). The National Trust. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ↑ "Church of Holy Trinity, Cookham - 1117568 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk.

- ↑ Oxley, G. W. "Cookham Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, Berkshire".

- ↑ "Cookham Parish Council". Cookham Parish Council. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ "Stanley Spencer Gallery".

- ↑ Bulbul, Nuray (22 May 2022). "Ulrika Jonsson health battle - TV presenter's age, marriages, children and stunning home". Oxfordshire Live. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ Denyer, Lucy (30 September 2012). "Stockholm is where Ulrika Jonsson's heart is". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ↑ Laughton, John Knox. – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin (1 January 2003). "Town bristles at 'gin and Jag' slur". The Guardian.

- ↑ "homepage". 87.9 FM. Bvoxy Ltd.

Sources

- Page, W.H.; Ditchfield, P.H., eds. (1923). "Cookham". A History of the County of Berkshire, Volume 3. Victoria County History. pp. 124–133.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1966). Berkshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 122–123.