The Count of Superunda | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Manso de Velasco as Viceroy of Peru, 1746 | |

| 30th Viceroy of Peru | |

| In office December 15, 1745 – October 12, 1761 | |

| Monarch | Ferdinand VI |

| Prime Minister | Marquis of Ensenada |

| Preceded by | José Antonio de Mendoza |

| Succeeded by | Manuel de Amat |

| Royal Governor of Chile | |

| In office November 15, 1737 – June 1744 | |

| Monarch | Philip V |

| Preceded by | Manuel de Salamanca |

| Succeeded by | Francisco José de Ovando |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 10, 1689 Torrecilla en Cameros, Spain |

| Died | January 5, 1767 (aged 77) Priego de Córdoba, Spain |

| Children | Diego Manso de Velasco |

| Profession | Brigadier General |

José Antonio Manso de Velasco y Sánchez de Samaniego, KOS (Spanish: José Antonio Manso de Velasco y Sánchez de Samaniego, primer Conde de Superunda) (May 10, 1689 – Jan 5, 1767) was a Spanish soldier and politician who served as governor of Chile and viceroy of Peru.

As Governor of Chile

Manso de Velasco served as governor of Chile from November 1737 to June 1744, during which time he stood out for his numerous projects. His tenure saw the construction of the first public food market in Santiago, irrigation canals on the Maipo River as well as breakwaters on the Mapocho River, the rebuilding of Valdivia (destroyed by an earthquake), and the celebration of an armistice with the indigenous Mapuche people, signed in the "Parlement of Tapihue".

In addition, he founded a large number of Chilean cities listed here with their current names, their given names, and their date of founding:

- Cauquenes (Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes), 1742

- Copiapó (San Francisco de la Selva), 1744

- Curicó (San José de Buena Vista), 1743

- Melipilla (San José de Logroño), 1742

- Rancagua (Santa Cruz de Triana), 1743

- San Felipe, 1740

- San Fernando (San Fernando de Tinguiririca), 1742

- Talca (San Agustín de Talca), 1742

His efficiency and diligence recommended him to a higher post, and Ferdinand VI named him viceroy of Peru in 1745, making him the first governor of Chile to be elevated in such a manner.

As Viceroy of Peru

_344.JPG.webp)

Manso de Velasco was the viceroy of Peru during the reign of Ferdinand VI of the House of Bourbon, holding the office from 1745 to October 12, 1761. He succeeded José Antonio de Mendoza, 3rd Marquis of Villagarcía and was replaced by Manuel de Amat y Juniet. The most important event of his tenure was the great earthquake of 1746.

Lima earthquake

On October 28, 1746 at around 10:30 at night, a major earthquake struck Lima and vicinity, resulting in one of the highest number of deaths for such an event in the area. Witnesses differ on the duration of the event, with reports ranging from 3 to 6 minutes. The intensity of the quake is today estimated at X or XI on the Mercalli intensity scale. The aftershocks, by the hundreds, continued for the following two months.

In Lima, the destruction was severe. Of 60,000 inhabitants, 1,141 were reported to have died. Only 25 houses remained standing. In Callao, a tsunami of nearly 17 meters in height penetrated up to 5 kilometers inland leaving only 200 survivors out of a population of 5,000. The fact that the earthquake struck at night probably contributed to the casualties, as many people were caught asleep in their homes. In the wake of the disaster, the population was gripped by hunger and fear.

As a result of this earthquake, building practices were modified, with the adobe style abandoned for quincha (wattle and daub) construction techniques, which resulted in more flexible structures that were more resistant to disruptive seismic activity.

On February 10, 1747 he founded the city of Bellavista.[1] On May 30, 1755 the cathedral of Lima was begun.

Last days

The aged and tired Manso de Velasco asked for permission to return to Spain for his retirement, and received a positive answer from the crown in 1761. However, his trip home took him through the port of Havana in the then-Captaincy General of Cuba, just at a time when the colony was under siege. The British laid siege to the port, and Manso de Velasco, nominally the highest-ranking military officer in the area, found himself named the "Chief of the War Council" by the Governor of Cuba. Thus, at age 74, he led the defense of the fortified city. Unfortunately, the troops under his command were poorly trained and their equipment was inferior, leading to a Spanish surrender after only 67 days.

Captured by the British, he was eventually brought to Cadiz in Spain. Due to his position as "Chief of the War Council", he was imprisoned in Madrid and tried by a court-martial presided over by the Count of Aranda. He and other accused chiefs were held responsible for the inglorious defeat in Cuba by this court-martial.[2] Charles III, King of Spain, ratified the sentences on March 4, 1765 ending the process. The sentences were not lenient, Manso de Velasco was condemned to 10 years of exile to 40 leagues from the Court, seizure of goods and he was made jointly responsible for compensating harmed Habaneros.[3]

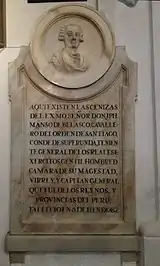

Shortly after being notified of the sentence Manso de Velasco left for his exile in Priego de Córdoba, where he arrived the same year. Less than two years later, on January 5, 1767, he died in the same city, where his remains still lay in the Church of San Pedro.[4]

References

- ↑ Kuethe, Allan J.; Andrien, Kenneth J. (May 12, 2014). "Clerical Reform and the Secularization of the Doctrinas de Indios". The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9781139916844. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ Martínez Millán, José; Camarero Bullón, Concepción; Luzzi Traficante, Marcelo (2013). "Víctimas ilustradas del Despotismo. El conde de Superunda, culpable y reo, ante el conde de Aranda". La corte de los Borbones, crisis del modelo cortesano. Chapter written by J. L. Gómez Urdañez. Ediciones Polifemo. pp. 1003–1033. ISBN 978-8496813816.

- ↑ Martínez Martín, Carmen (2006). "Linaje y nobleza del virrey don José Manso de Velasco, conde de Superunda". Revista Complutense de Historia de América. 32: 269–280. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Abierta la tumba del Conde de Superunda con motivo de la restauración de San Pedro" (PDF). ADARVE. 372: 16–17. December 1, 1991. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

_Pillars_of_Hercules_Variant.svg.png.webp)