The cephalic index or cranial index is a number obtained by taking the maximum width (biparietal diameter or BPD, side to side) of the head of an organism, multiplying it by 100 and then dividing it by their maximum length (occipitofrontal diameter or OFD, front to back). The index was once used to categorize human beings in the first half of the 20th century, but today it is used to categorize dogs and cats.

Historic use in anthropology

Early anthropology

The cephalic index was used by anthropologists in the early 20th century as a tool categorize human populations. It was used to describe an individual's appearance and for estimating the age of fetuses for legal and obstetrical reasons.

The cephalic index was defined by Swedish professor of anatomy Anders Retzius (1796–1860) and first used in physical anthropology to classify ancient human remains found in Europe. The theory became closely associated with the development of racial anthropology in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when historians attempted to use ancient remains to model population movements in terms of racial categories. American anthropologist Carleton S. Coon also used the index in the 1960s, by which time it had been largely discredited.

In the cephalic index model, human beings were characterized by having either a dolichocephalic (long-headed), mesaticephalic (moderate-headed), or brachycephalic (short-headed) cephalic index or cranial index.

Indices

Cephalic indices are grouped as in the following table:

| Females | Males | Scientific term | Meaning | Alternative term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 75 | < 75.9 | dolichocephalic | 'long-headed' | |

| 75 to 83 | 76 to 81 | mesaticephalic | 'medium-headed' | mesocephalic; mesocranial |

| > 83 | > 81.1 | brachycephalic | 'short-headed' | brachycranial |

Technically, the measured factors are defined as the maximum width of the bones that surround the head above the supramastoid crest (behind the cheekbones), and the maximum length from the most easily noticed part of the glabella (between the eyebrows) to the most easily noticed point on the back part of the head.

Controversy

The usefulness of the cephalic index was questioned by Giuseppe Sergi, who argued that cranial morphology provided a better means to model racial ancestry.[1] Also, Franz Boas studied the children of immigrants to the United States in 1910 to 1912, noting that the children's cephalic index differed significantly from their parents', implying that local environmental conditions had a significant effect on the development of head shape.[2]

Boas argued that if craniofacial features were so malleable in a single generation, then the cephalic index was of little use for defining race and mapping ancestral populations. Scholars such as Earnest Hooton continued to argue that both environment and heredity were involved. Boas did not himself claim it was totally plastic.

In 2002, a paper by Sparks and Jantz re-evaluated some of Boas's original data using new statistical techniques and concluded that there was a "relatively high genetic component" of head shape.[3] Ralph Holloway of Columbia University argues that the new research raises questions about whether the variations in skull shape have "adaptive meaning and whether, in fact, normalizing selection might be at work on the trait, where both extremes, hyperdolichocephaly and hyperbrachycephaly, are at a slight selective disadvantage."[2]

In 2003, anthropologists Clarence C. Gravlee, H. Russell Bernard, and William R. Leonard reanalyzed Boas's data and concluded that most of Boas's original findings were correct. Moreover, they applied new statistical, computer-assisted methods to Boas's data and discovered more evidence for cranial plasticity.[4] In a later publication, Gravlee, Bernard and Leonard reviewed Sparks's and Jantz's analysis. They argue that Sparks and Jantz misrepresented Boas's claims, and that Sparks's and Jantz's data support Boas. For example, they point out that Sparks and Jantz look at changes in cranial size in relation to how long an individual has been in the United States in order to test the influence of the environment. Boas, however, looked at changes in cranial size in relation to how long the mother had been in the United States. They argue that Boas's method is more useful, because the prenatal environment is a crucial developmental factor.[4]

Jantz and Sparks responded to Gravlee et al., reiterating that Boas' findings lacked biological meaning, and that the interpretation of Boas' results common in the literature was biologically inaccurate.[5] In a later study, the same authors concluded that the effects Boas observed were likely the result of population-specific environmental effects such as changes in cultural practices for cradling infants, rather than the effects of a general "American environment" which caused populations in America to converge to a common cranial type, as Boas had suggested.[6][7]

Vertical cephalic index

The vertical cephalic index, also known as the length-height index, was a less-commonly measured head ratio.[8][9] In the vertical cephalic index model, humans beings were characterized by having either a chamaecranic (low-skulled), orthocranic (medium high-skulled), or hypsicranic (high-skulled) cephalic index or cranial index.

Medicine

The cephalic index is also used in medicine, especially in the planning and effectiveness analysis of cranial deformity corrections.[10] The index is a useful tool in assessing the morphology of cranial deformities in clinical settings.[11] The index is used while looking at the fetal head shape, and can change in certain situations (ex. breech presentation, ruptured membranes, twin pregnancy).[12]

Modern use in animal breeding

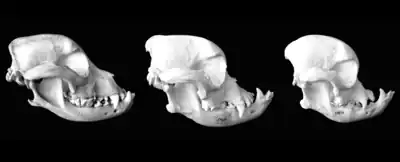

The cephalic index is used in the categorisation of animals, especially breeds of dogs and cats.

Brachycephalic animals

A brachycephalic skull is relatively broad and short (typically with the breadth at least 80% of the length). Dog breeds such as the pug are sometimes classified as "extreme brachycephalic".[13] Because of the health issues brachycephaly is regarded as torture breeding[14][15][16][17] as it often leads to the brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome.

List of brachycephalic dogs

%252C_February_2010.JPG.webp)

- Affenpinscher

- American Bulldog

- American Bully

- Boston Terrier

- Boxer

- Brussels Griffon

- Bulldog

- Bullmastiff

- Cane Corso

- Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

- Apple-headed Chihuahua

- Chow Chow

- Dogo Argentino

- Dogue de Bordeaux

- English Mastiff

- English Bulldog

- Fila Brasileiro

- French Bulldog

- Japanese Chin

- King Charles Spaniel

- Lhasa Apso

- Lowchen

- Neapolitan Mastiff

- Newfoundland

- Olde English Bulldogge

- Pekingese

- Perro de Presa Canario

- Pit bull

- Pug

- Pyrenean Mastiff

- Shar-Pei

- Shih Tzu

- Tibetan Spaniel

- Tosa

List of brachycephalic cats

List of brachycephalic pigs

- Middle White

- Neijiang

List of brachycephalic rabbits

- Lionhead rabbit

- Lop rabbit

- Netherland Dwarf rabbit

- Dwarf Papillon rabbit

- Dwarf Hotot rabbit

- Jersey Wooly rabbit

- American Fuzzylop rabbit

Other

Mesaticephalic animals

A mesaticephalic skull is of intermediate length and width. Mesaticephalic skulls are not markedly brachycephalic or dolichocephalic. When dealing with animals, especially dogs, the more appropriate and commonly used term is not "mesocephalic", but rather "mesaticephalic", which is a ratio of head to nasal cavity. The breeds below exemplify this category.[23][24]

List of mesaticephalic canines

- African Wild Dog

- Alaskan Malamute

- almost all spaniels

- almost all spitz, except for the Chow Chow

- American Eskimo Dog

- American Foxhound

- Appenzeller Sennenhund

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Australian Shepherd

- Basenji

- Beagle

- Bearded Collie

- Beauceron

- Belgian Malinois

- Belgian Sheepdog

- Bernese Mountain Dog

- Bichon Frisé

- Black and Tan Coonhound

- Border Collie

- Cardigan Welsh Corgi

- Chesapeake Bay Retriever

- pear- and deer-headed Chihuahuas

- Chinese Crested

- Chinook

- Curly-Coated Retriever

- Dalmatian

- Dhole

- English Foxhound

- Field Spaniel

- Finnish Lapphund

- Finnish Spitz

- Flat-Coated Retriever

- German Shorthaired Pointer

- German Wirehaired Pointer

- German Spitz

- Golden Retriever

- Irish Setter

- Komondor

- Labrador Retriever

- Miniature Pinscher

- Pomeranian

- Poodle (Miniature and Toy)

- most terriers

- Mudi

- Pembroke Welsh Corgi

- Puli

- Rottweiler

- Samoyed

- Siberian Husky

- St. Bernard

- Vizsla

- Weimaraner

- Wirehaired Vizsla

- Xoloitzcuintle

List of mesaticephalic cats

Note: Almost all domestic felines are mesaticephalic

- Abyssinian

- American Shorthair

- American Bobtail

- Bengal cat

- Birman

- Bombay cat

- Burmese cat

- Chartreux

- Chausie

- Colorpoint Shorthair

- Cymric cat

- Egyptian Mau

- Felid hybrids

- Felis, or small cats

- Maine Coon

- Manx

- Munchkin cat

- Norwegian forest cat

- Ocicat

- Pallas's cat

- Ragdoll

- Russian Blue

- Russian White, Black and Tabby

- Selkirk Rex

- Siberian cat

- Somali

- Toyger

- Turkish Angora

- Turkish Van

List of mesaticephalic rabbits

Other

Dolichocephalic animals

A dolichocephalic skull is relatively long-headed (typically with the breadth less than 80% or 75% of the length).

Note: Almost all representatives of the infraphylum Gnathostomata (with rare exceptions) are dolichocephalic.

List of dolichocephalic canids

Note: Almost all canidae are dolichocephalic

- Afghan Hound

- Airedale Terrier

- Azawakh

- Basset Hound

- Bedlington Terrier

- Bloodhound

- Borzoi

- Bull terrier

- Cesky Terrier

- Coyote

- Dachshund

- Doberman Pinscher

- Dingo

- Fox Terrier

- Galgo Español

- German Shepherd Dog

- Great Dane

- Greyhound

- Irish Terrier

- Irish Wolfhound

- Italian Greyhound

- Kangaroo hound

- Kanni

- Kerry Blue Terrier

- Khalag Tazi

- Long dog

- Lurcher

- Manchester Terrier

- Miniature Bull Terrier

- Peruvian Inca Orchid

- Pharaoh Hound

- Poodle (Standard)

- Rampur Greyhound

- Red fox

- Rough Collie

- Russian Black Terrier

- Saluki

- Schnauzer

- Scottish Deerhound

- Scottish Terrier

- Sealyham Terrier

- Serbian Hound

- Shetland Sheepdog

- Silken Windhound

- Sloughi

- Smooth Collie

- Taigan

- Welsh Terrier

- Whippet

- Wolf

List of dolichocephalic felines

List of dolichocephalic leporids

- English Spot

- English Lop

- Belgian Hare

- All true hares

Other

See also

References

- ↑ Killgrove K (2005). Bioarchaeology in the Roman World (PDF) (Masters thesis). UNC Chapel Hill. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2012.

- 1 2 Holloway RL (November 2002). "Head to head with Boas: did he err on the plasticity of head form?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 14622–3. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914622H. doi:10.1073/pnas.242622399. PMC 137467. PMID 12419854.

- ↑ Sparks CS, Jantz RL (November 2002). "A reassessment of human cranial plasticity: Boas revisited". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 14636–14639. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914636S. doi:10.1073/pnas.222389599. PMC 137471. PMID 12374854.. See also the discussion in Holloway RL (November 2002). "Head to head with Boas: did he err on the plasticity of head form?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 14622–14623. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914622H. doi:10.1073/pnas.242622399. PMC 137467. PMID 12419854.

- 1 2 Gravlee CC, Bernard HR, Leonard WR (March 2003). "Heredity, environment, and cranial form: A reanalysis of Boas's immigrant data" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 105 (1): 125–138. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.125. hdl:2027.42/65137. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Sparks CS, Jantz RL (2003). "Changing Times, Changing Faces: Franz Boas's Immigrant Study in Modern Perspective". American Anthropologist. 105 (2): 333–337. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.2.333.

- ↑ Jantz RL, Logan MH (2010). "Why does head form change in children of immigrants? A reappraisal". American Journal of Human Biology. 22 (5): 702–707. doi:10.1002/ajhb.21070. PMID 20737620. S2CID 12686512.

- ↑ Spradley MK, Weisensee K (2017). "Ancestry Estimation: The Importance, The History, and The Practice". In Langley NR, Tersigni-Tarrant MT (eds.). Forensic Anthropology: A Comprehensive Introduction (Second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-1-4987-3612-1.

- ↑ https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/length-height%20index.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Chandrashekhar, Chikatapu; Salve, Vishal Manoharrao (2013). "The Study of Vertical Cephalic Index (Length-Height Index) and Transverse Cephalic Index (Breadth-Height Index) of Andhra Region (India)". Asian Journal of Medical Sciences. 3 (3): 6–11. doi:10.3126/ajms.v3i3.4650.

- ↑ Likus, Wirginia; Bajor, Grzegorz; Gruszczynska, Katrzyna; Baron, Jan; Markowski, Jaroslaw; Machnikowska-Sokolowska, Magdalena; Milka, Daniela; Lepich, Tomasz (4 February 2014). "Cephalic Index in the First Three Years of Life: Study of Children with Normal Brain Development Based on Computed Tomography". TheScientificWorldJournal. 2014: 502836. doi:10.1155/2014/502836. PMC 3933399. PMID 24688395.

- ↑ Nam, Heesung; Han, Nami; Eom, Mi Ja; Kook, Minjung; Kim, Jeeyoung (30 April 2021). "Cephalic Index of Korean Children With Normal Brain Development During the First 7 Years of Life Based on Computed Tomography". Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine. 45 (2): 141–149. doi:10.5535/arm.20235. ISSN 2234-0645. PMC 8137378. PMID 33985316.

- ↑ Weerakkody, Yuranga. "Cephalic index | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ↑ "Brachycephalic Health". www.thekennelclub.org.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ↑ FOUR PAWS International: The suffering of dogs with genetic disorders

- ↑ Anne Fawcett, Vanessa Barrs, Magdoline Awad et al.: Consequences and Management of Canine Brachycephaly in Veterinary Practice: Perspectives from Australian Veterinarians and Veterinary Specialists

- ↑ Border Wars: Torture breeding

- ↑ FECAVA: Brachycephalic issues: shared resources

- ↑ Lowrey, Sassafras (10 June 2022). "Brachycephalic Dog Breeds: A Guide to Flat-Faced Dogs". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ "Brachycephalic Breeds of Cats | ASPCA Pet Health Insurance". www.aspcapetinsurance.com. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ↑ "Breathing Problems in Flat-faced Cat Breeds | Purina". www.purina-arabia.com. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- 1 2 Geiger M, Schoenebeck JJ, Schneider RA, Schmidt MJ, Fischer MS, Sánchez-Villagra MR (14 August 2021). "Exceptional Changes in Skeletal Anatomy under Domestication: The Case of Brachycephaly". Integrative Organismal Biology. 3 (1): obab023. doi:10.1093/iob/obab023. PMC 8366567. PMID 34409262.

- ↑ "Brachy breeds – not just dogs! Rabbits too". 24 March 2017.

- ↑ Evans HE (1994). Miller's Anatomy of the Dog (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 132. ISBN 9780721632001. OCLC 827702042.

- ↑ mesaticephalic. 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2019 – via The Free Dictionary.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

- Cephalic index

- Brachycephalic Experienced Veterinarians Database Archived 30 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine