A diagram is a symbolic representation of information using visualization techniques. Diagrams have been used since prehistoric times on walls of caves, but became more prevalent during the Enlightenment.[1] Sometimes, the technique uses a three-dimensional visualization which is then projected onto a two-dimensional surface. The word graph is sometimes used as a synonym for diagram.

Overview

The term "diagram" in its commonly used sense can have a general or specific meaning:

- visual information device : Like the term "illustration", "diagram" is used as a collective term standing for the whole class of technical genres, including graphs, technical drawings and tables.

- specific kind of visual display : This is the genre that shows qualitative data with shapes that are connected by lines, arrows, or other visual links.

In science the term is used in both ways. For example, Anderson (1997) stated more generally: "diagrams are pictorial, yet abstract, representations of information, and maps, line graphs, bar charts, engineering blueprints, and architects' sketches are all examples of diagrams, whereas photographs and video are not".[2] On the other hand, Lowe (1993) defined diagrams as specifically "abstract graphic portrayals of the subject matter they represent".[3]

In the specific sense diagrams and charts contrast with computer graphics, technical illustrations, infographics, maps, and technical drawings, by showing "abstract rather than literal representations of information".[4] The essence of a diagram can be seen as:[4]

- a form of visual formatting devices

- a display that does not show quantitative data (numerical data), but rather relationships and abstract information

- with building blocks such as geometrical shapes connected by lines, arrows, or other visual links.

Or in Hall's (1996) words "diagrams are simplified figures, caricatures in a way, intended to convey essential meaning".[5] These simplified figures are often based on a set of rules. The basic shape according to White (1984) can be characterized in terms of "elegance, clarity, ease, pattern, simplicity, and validity".[4] Elegance is basically determined by whether or not the diagram is "the simplest and most fitting solution to a problem".[6]

Diagrammatology

Diagrammatology is the academic study of diagrams. Scholars note that while a diagram may look similar to the thing that it represents, this is not necessary. Rather a diagram may only have structural similarity to what it represents, an idea often attributed to Charles Sanders Peirce.[7]: 42 Structural similarity can be defined in terms of a mapping between parts of the diagram and parts of what the diagram represents and the properties of this mapping, such as maintaining relations between these parts and facts about these relations. This is related to the concept of isomorphism, or homomorphism in mathematics.[7]: 43

Sometimes certain geometric properties (such as which points are closer) of the diagram can be mapped to properties of the thing that a diagram represents. On the other hand, the representation of an object in a diagram may be overly specific and properties that are true in the diagram may not be true for the object the diagram represents.[7]: 48 A diagram may act as a means of cognitive extension allowing reasoning to take place on the diagram based on which constraints are similar.[7]: 50

Gallery of diagram types

There are at least the following types of diagrams:

Logical

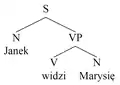

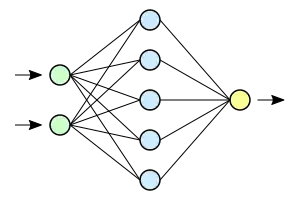

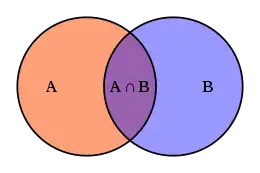

- Logical or conceptual diagrams, which take a collection of items and relationships between them, and express them by giving each item a 2D position, while the relationships are expressed as connections between the items or overlaps between the items, for example:

Quantitative

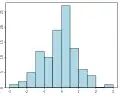

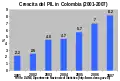

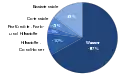

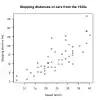

- Quantitative diagrams, which display a relationship between two variables that take either discrete or a continuous range of values; for example:

Hanger diagram.

Hanger diagram.

Schematic

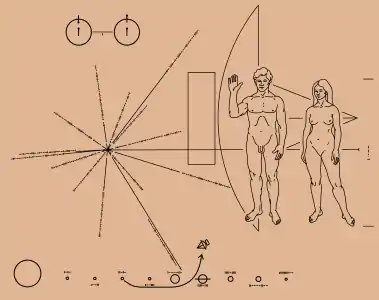

- Schematics and other types of diagrams, for example:

Many of these types of diagrams are commonly generated using diagramming software such as Visio and Gliffy.

Diagrams may also be classified according to use or purpose, for example, explanatory and/or how to diagrams.

Thousands of diagram techniques exist. Some more examples follow:

Specific diagram types

See also

- commons:Specific diagram types – Gallery of many diagram types at Wikimedia Commons

- Chart – Graphical representation of data

- Data and information visualization – Visual representation of data

- Diagrammatic reasoning – reasoning by the mean of visual representations

- Diagrammatology

- Experience model

- JavaScript graphics libraries – Libraries for creating diagrams and other data visualization

- List of graphical methods

- Mathematical diagram – Visual representation of a mathematical relationship

- PGF/TikZ – Graphics languages

- Plot (graphics) – Graphical technique for data sets

- Table (information) – Arrangement of information or data, typically in rows and columns

References

- ↑ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2021). "Diagrams". In Blair, Ann; Duguid, Paul; Goeing, Anja-Silvia; Grafton, Anthony (eds.). Information: A Historical Companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 397–401. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1pdrrbs.42. ISBN 9780691179544. JSTOR j.ctv1pdrrbs.42. OCLC 1202730160. S2CID 240873019.

- ↑ Michael Anderson (1997). "Introduction to Diagrammatic Reasoning", at cs.hartford.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ↑ Lowe, Richard K. (1993). "Diagrammatic information: techniques for exploring its mental representation and processing". Information Design Journal. 7 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1075/idj.7.1.01low.

- 1 2 3 Brasseur, Lee E. (2003). Visualizing technical information: a cultural critique. Amityville, N.Y: Baywood Pub. ISBN 0-89503-240-6.

- ↑ Bert S. Hall (1996). "The Didactic and the Elegant: Some Thoughts on Scientific and Technological Illustrations in the Middle Ages and Renaissance". in: B. Braigie (ed.) Picturing knowledge: historical and philosophical problems concerning the use of art in science. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p.9

- ↑ White, Jan V. (1984). Using charts and graphs: 1000 ideas for visual persuasion. New York: Bowker. ISBN 0-8352-1894-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Pombo, Olga; Gerner, Alexander, eds. (2010). Studies in Diagrammatology and Diagram Praxis. London: College Publications. ISBN 978-1-84890-007-3. OCLC 648770148.

Further reading

- Bounford, Trevor (2000). Digital diagrams. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 978-0-8230-1572-6.

- Michael Anderson, Peter Cheng, Volker Haarslev (Eds.) (2000). Theory and Application of Diagrams: First International Conference, Diagrams 2000. Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, September 1–3, 2000. Proceedings.

- Garcia, M. (ed.), (2012) The Diagrams of Architecture. Wiley. Chichester.

- Birger Sevaldson, Designing Complexity. Common Ground Research Networks. 2022. ISBN 978-0-949313-61-4.

External links

- What is Gigamapping (website provided by the Oslo School of Architecture and Design)

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)