Eighth Avenue Local | |

| |

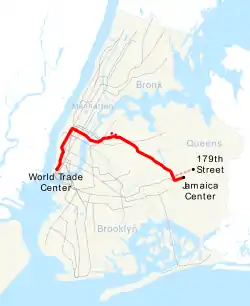

Note: This map represents normal service. Dashed line shows late night only service Dashed pink line shows weekday rush hour, midday and early evening service to 179th Street, temporarily suspended | |

| Northern end | Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer |

|---|---|

| Southern end | World Trade Center |

| Stations | 22 (weekday rush hour, midday and early evening service to/from Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer) 24 (early evening and weekends) 32 (late nights) |

| Rolling stock | 260 R160s (26 trains)[1][2] (Rolling stock assignments subject to change) |

| Depot | Jamaica Yard |

| Started service | August 19, 1933 |

The E Eighth Avenue Local[3] is a rapid transit service in the B Division of the New York City Subway. Its route emblem, or "bullet", is blue since it uses the IND Eighth Avenue Line in Manhattan.

The E operates at all times between Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer in Jamaica, Queens, and the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. Additional service during weekday rush hours originates and terminates at Jamaica–179th Street instead of Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer (this service is suspended until 2024 due to construction on the IND 63rd Street Line). Daytime service operates express in Queens[lower-alpha 1] and local in Manhattan; late night service makes local stops along its entire route.

E service, which is one of the most heavily used services in the subway system, started in 1933 with the opening of the IND Queens Boulevard Line. In its early years, the E train ran along the Rutgers Street Tunnel and South Brooklyn Line to Brooklyn, though this service pattern stopped by 1940. Until 1976, the E train ran to Brooklyn and Queens via the IND Fulton Street Line and IND Rockaway Line during rush hours and to the World Trade Center at other times. The E's northern terminal was switched from 179th Street to Jamaica Center with the opening of the IND Archer Avenue Line in 1988.

History

Creation and extensions

E service began with the opening of the IND Queens Boulevard Line from 50th Street to Roosevelt Avenue on August 19, 1933, running between Roosevelt Avenue and Hudson Terminal (current World Trade Center station) on the IND Eighth Avenue Line. Because the IND Crosstown Line did not yet fully open, and as the IND Queens Boulevard Line had not yet opened to Jamaica, service ran via the Queens Boulevard Line's local tracks. The E also ran local in Manhattan.[4][5][6] Initially, weekday service ran every four minutes during rush hours, every five minutes middays, every six or eight minutes evenings, and every twelve minutes overnights. Service ran every four or five minutes during the Saturday morning rush hour, every five minutes during the morning and afternoon, and every six or eight minutes in the evening. On Sunday, E trains ran every six or seven minutes in the morning, every five minutes in the afternoon, and every six or eight minutes in the evening.[7] Service was provided by three-car trains during rush hours and two-car trains at other times.[8] By January 16, 1934, rush hour service was operating with three- or four-car trains.[9]

E trains were extended to East Broadway following the opening of the IND Sixth Avenue Line from West Fourth Street on January 1, 1936. E trains no longer served stations on the Eighth Avenue Line south of West Fourth Street.[10][6] On April 9 of the same year, the Sixth Avenue Line was extended through the Rutgers Street Tunnel to Jay Street–Borough Hall, and E trains were extended via this line and the IND South Brooklyn Line to Church Avenue, replacing the A train, which was rerouted via the new IND Fulton Street Line to Rockaway Avenue.[11][6] The E service was again extended with the opening of the Queens Boulevard Line extension to Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike on December 31, 1936.[12][13]

Express service along Queens Boulevard began on April 24, 1937, coinciding with the extension of the line and E service to 169th Street.[14][15] Express service was inaugurated during rush hours, with E trains making express stops from 71st–Continental Avenues to Queens Plaza. The express service operated between approximately 6:30 and 10:30 a.m. and from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m.[16] Express service was also provided on Saturdays between 6:30 a.m. and 4 p.m. During rush hours, GG trains were extended to Continental Avenue from Queens Plaza, taking over the local service. During non-rush hours, when GG service terminated at Queens Plaza, local service was provided by EE trains, which operated between 169th Street and Church Avenue in Brooklyn.[6][17][18] The initial headway for express service was between three and five minutes.[19] With the completion of the Crosstown Line on July 1, 1937, non-rush hour GG service was extended to 71st Avenue, allowing E trains to run express along Queens Boulevard west of 71st Avenue at all times. EE service was discontinued at this time. In addition, three southbound E trains began service at 71st Avenue between 8:07 and 8:28 a.m. during the morning rush hour.[6][20][21] The headway between trains during the peak of rush hour was reduced to three minutes at this time.[9]

On September 12, 1938, nine weekday rush hour trains began terminating at Jay Street between 7:45 and 8:30 a.m. Five of these trips originated at 169th Street, while the other four began service at Parsons Boulevard.[8] Four northbound E trains entered service at Smith–Ninth Streets between 4:52 and 5:25 p.m. on weekdays.[6][20][21] The additional service allowed for a peak two-minute headway for twelve minutes in the morning rush hour southbound.[7] The 23rd Street–Ely Avenue station opened as an in-fill station on August 28, 1939, and was served by the E service during rush hours, and by the EE service during other times.[22] Between April 1939 and October 1940, select evening E trains ran to and from the Horace Harding Boulevard terminal at the 1939 New York World's Fair, terminating at Hudson Terminal in Manhattan. These trains operated to and from Chambers Street and ran between 8:24 p.m. and 1:29 a.m., when the fair closed for the night. Service ended following the fair.[6][23][24]

On December 15, 1940, service on the entire Sixth Avenue Line began, and service patterns across the IND were modified. E service was cut back to Broadway–Lafayette Street, and service south of that station to Church Avenue was replaced by the new F train along Sixth Avenue.[25] The new F service supplemented E express along Queens Boulevard, and allowed for the introduction of express service along Queens Boulevard between 71st Avenue and Parsons Boulevard.[6] F trains terminated at Parsons Boulevard instead of 169th Street to reduce congestion at the two stations.[26] Starting January 10, 1944, some E trains began terminating at 71st Avenue after the weekday and Saturday morning rush hour, and some originated there during the evening rush hour.[6][20] In addition, the headway of late night service was increased from twelve minutes to fifteen minutes.[7]

In 1949, Saturday afternoon trains were cut back from eight cars to five cars.[27] On October 24, 1949, the E was extended during weekday rush hours to Broadway–East New York, running local via the Fulton Street Line to allow A trains to run express.[28] Several trains continued to terminate at 71st Avenue after the morning rush hour.[6] At the same time, the headway between rush hour trains in the peak-direction was reduced from four minutes to three minutes.[7] The Queens Boulevard Line's extension to 179th Street opened on December 11, 1950, and E trains were extended from 169th Street to terminate there.[29][30] In 1952, trains were lengthened from five-car trains to six-car trains on Saturday mornings, afternoons, and evenings.[27]

On June 30, 1952, two morning rush hour trips on the E train were added, running between 71st Avenue and Jay Street.[6] Midday service began operating on eight-minute headways instead of six-minute headways, evening service began operating on ten-minute headways instead of eight-minute headways, and late night service began operating on twenty-minute headways, instead of fifteen-minute headways. With the July 5, 1952 timetable, E trains began running every eight minutes during the morning and afternoon on Saturday, instead of every six minutes during the morning rush hour, and every seven minutes during the morning and afternoon. During late evenings, trains began running every twelve minutes instead of every eight minutes.[7]

In 1953, the platforms were lengthened at 75th Avenue, Sutphin Boulevard, Spring Street, Canal Street, Ralph Avenue, and Broadway–East New York to 660 feet (200 m) to allow E and F trains to run eleven-car trains. The E and F began running eleven-car trains during rush hours on September 8, 1953. The extra train car increased the total carrying capacity by 4,000 passengers. The lengthening project cost $400,000.[31]

On October 30, 1954, the E service was modified as part of a series of service changes made following the completion of the Culver Ramp, which made it possible for IND service on the Culver Line to run to Coney Island. Non-rush hour E service was rerouted from Broadway–Lafayette Street to Hudson Terminal, and E trains began running express in Manhattan during rush hours, when they headed to Brooklyn.[6][32][27] In 1955, late night trains were cut back from five-car trains to three-car trains, and midday and evening trains were lengthened from six-car trains to eight-car trains. A year later, late night trains were lengthened to operate with four-car trains instead of three-car trains.[27]

Changes in Brooklyn service

On June 28, 1956, the Long Island Rail Road's Rockaway Beach Branch reopened as the IND Rockaway Line after being converted for subway service,[33] and E service was extended from East New York to Rockaway Park or Wavecrest (now Beach 25th Street) during weekday rush hours. During non-rush hours, service was provided by four-car shuttles between Euclid and Rockaway Park or Wavecrest.[34][35] Three weekday E trains leaving 179th Street between 6:54 and 7:27 a.m. were cut at Euclid Avenue, with one half of the train running to Far Rockaway, and the other half going to Rockaway Park. After the end of the morning rush hour, several trains terminated at East New York, before going back into Manhattan-bound service before the afternoon rush hour.[6][36]

On September 17, 1956, rush hour E service was cut back to Euclid Avenue when Rockaway service was replaced by the A train.[20][36] The A and E later switched southern terminals again, and on September 8, 1958, the E began running to Far Rockaway and Rockaway Park during rush hours, with some trips terminating at Euclid Avenue. During weekday off-peak hours, separate shuttles operated from Euclid Avenue to Far Rockaway and Rockaway Park. At the same time, round-robin service began during weekend and late night service, because of the low ridership at these times. These trains would run from Euclid Avenue to Rockaway Park, and then reverse and run to Far Rockaway, before returning to Euclid Avenue.[6][37]: 216

The operation of eleven-car trains ended on August 18, 1958, because of operational difficulties. The signal blocks, especially in Manhattan, were too short to accommodate the longer trains, and the train operators had a very small margin of error to properly platform the train. It was found that operating ten-car trains allowed for two additional trains per hour to be scheduled.[38] To make up for the loss of eleven-car trains, two short-run trains from 71st Avenue were added on the E and F during rush hours.[39]

On October 11, 1958, round-robin service ceased operating on weekends, being by replaced by shuttles running from Euclid Avenue to either terminal in the Rockaways. Round-robin service continued to operate late evenings, late nights, and early mornings. From October to June, round-robin service started at 6:40 p.m. leaving Euclid Avenue, and from June to October the service began at 9:44 p.m. from Euclid Avenue.[6]

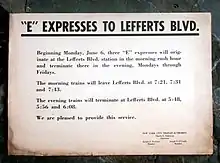

Since many Rockaway riders were dissatisfied with having rush hour service provided by local trains, starting on November 3, 1958, four morning rush hour E trains ran express via the Fulton Street Line from Euclid Avenue: two from Rockaway Park, and two from Far Rockaway. To make up for the loss of local service along the Fulton Street Line, four A trains leaving Euclid Avenue between 7:56 a.m. and 8:24 a.m. began making local stops.[6][36] All E trains began running express and all A trains began running local to Euclid Avenue on September 8, 1959.[20][40] On June 6, 1960, three E trains started originating at Lefferts Boulevard in the morning rush hour and three E trains began terminating there in the evening rush hour, after complaints from riders.[41][42] Shuttles between Euclid Avenue and the Rockaways, which had not been assigned a route designation, but often were signed as E trains, were labeled HH trains on February 1, 1962.[6]

In 1964, E trains were cut back from five-car trains to four-car trains on Saturday late nights and to three-car trains on Sunday late nights. In addition, trains were lengthened from five cars to six cars on Sunday mornings, afternoons, and evenings. Two additional E trains began running from 169th Street during the morning rush hour on April 6, 1964; these trips began entering service at 179th Street on December 21, 1964.[27] On July 11, 1966, midday service began running every ten minutes, instead of every eight, and evening service began running every twelve minutes, instead of every ten.[7] At the same time, midday and evening trains began running with ten-car trains instead of eight-car trains, and late night trains were extended from four-car trains to five-car trains.[27] Midday and evening shuttles between the Rockaways and Euclid Avenue were replaced by the A service on July 10, 1967.[34]

In October 1969, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) performed a test over the course of a month to evaluate the impact that increasing the scheduled frequency of the E and F services along the Queens Boulevard Line in the southbound direction in the morning would have on running times and the number of trains that actually ran in service. As part of the test, 35 trains were scheduled to leave 179th Street during the morning peak hour, 17 E trains and 18 F trains. However, only 32 trains actually left the terminal, 15 E trains and 17 F trains. The study found that the average number of trains actually in service was 28 at Queens Plaza, 14 Es and 14 Fs, and 31 at 71st Avenue, 15 Es and 16 Fs, and that running such a high frequency of service was not possible without increasing running times and causing congestion.[43]

.svg.png.webp)

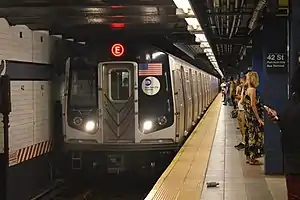

Southbound E trains began stopping at the lower level of the 42nd Street station during rush hours on March 23, 1970, to reduce delays by relieving congestion on the station's platforms.[44][45] The frequency of weekend service was decreased on July 3, when trains started running every ten minutes on Saturdays and every twelve minutes on Sundays.[46]

As part of systemwide changes in bus and subway service on January 2, 1973, the E became the local in Brooklyn again, running alternatively to Euclid Avenue and Rockaway Park–Beach 116th Street on weekdays from 6:15 a.m. to 9 a.m. and from 3:35 p.m. to 6:15 p.m.. The span of express service in Manhattan and through service to Brooklyn and the Rockaways during rush hours was doubled. The E would no longer also serve Far Rockaway during rush hours, with this service provided by the A.[34][47] During other times, except when Round-Robin service operated, E shuttle service would run from Broad Channel to Rockaway Park. A trains would run express instead in Brooklyn during rush hours, though for a longer period of time, and would take over service to Far Rockaway.[48][49][50] These changes were initially supposed to take effect on September 11, 1972.[51]

On January 19, 1976, rush hour service on the E was decreased. Northbound rush hour service began running every four or five minutes, instead of every four, and southbound evening rush hour service began running every four or six minutes, instead of every four.[7] Finally, on August 30, 1976, E service in Brooklyn was eliminated with all trains terminating at World Trade Center. Brooklyn service was replaced by the CC local.[52][53] On January 24, 1977, as part of a series of NYCTA service cuts to save $13 million, many subway lines began running shorter trains during middays. As part of the change, E trains began running with six cars between 9:50 a.m. and 1:30 p.m.[54] On August 30, 1976, some E trains began terminating at 71st Avenue after the morning rush hour.[20] Until 1986, two E trains and two F trains started at 71st Avenue in the morning rush hour with the intention to relieve congestion. These trains were eliminated because they resulted in a loading imbalance, as these lightly-loaded trains would be followed by extremely crowded trains from 179th Street, which followed an eight-minute gap of E and F service from 179th Street.[55]: 51

In 1986, the NYCTA studied which two services should serve the Queens Boulevard Line during late nights as ridership at this time did not justify three services. A public hearing was held in December 1986, and it was determined that having the E and R, which would replace the N, run during late nights provided the best service.[55]: 51 On May 24, 1987, ten-minute frequencies on E during evenings were extended by an additional hour to 9 p.m.[56]

Archer Avenue changes

On December 11, 1988, the Archer Avenue Lines opened, and E trains were rerouted via this branch, running to Jamaica Center via the Queens Boulevard Line's express tracks. E trains began running express east of 71st Avenue, skipping 75th Avenue and Van Wyck Boulevard at all times,[57][58] with local service to 179th Street replaced by the R, which was extended to 179th Street from 71st Avenue. The R extension allowed F trains to continue running express to 179th Street.[59][60] It was decided to serve Archer Avenue with the E as opposed to the F to minimize disruption to passengers who continued to use Hillside Avenue, to maximize Jamaica Avenue ridership and the length of the peak ridership period, which is longer on the F. It was found that most riders using buses diverted to Archer Avenue used the E, while passengers on buses to 179th Street used the F. Having E trains run local between 71st Avenue and Van Wyck Boulevard was dismissed in order to provide 24 hour express service to the Archer Avenue Line.[55]: 55

Two service plans were identified prior to a public hearing on February 25, 1988, concerning the service plan for the new extension. The first would have split rush-hour E service between the two branches, with late night service to 179th Street provided by the R, while the second would have had all E trains run via Archer Avenue, and would have extended R locals to 179th Street.[61][55]: 9–10 A modified version of the second plan was decided upon. The change in the plan was the operation of alternate E trains from 179th Street as expresses during the morning rush hour between 7:07 and 8:19 a.m. to provide an appropriate level of E service to Archer during the morning rush, to maintain the same level of service to 179th Street while providing express service, and to provide greater choice for riders at the Parsons Boulevard and 179th Street stations on Hillside Avenue. It was decided not to divert some E trains to 179th Street during the afternoon rush hour so that Queens-bound riders would not be confused about where their E train was headed.[55]: 9–10 [56]

The 1988 changes angered some riders because they resulted in the loss of direct Queens Boulevard Express service at local stations east of 71st Avenue (169th Street, Sutphin Boulevard, Van Wyck Boulevard and 75th Avenue stations). Local elected officials pressured the MTA to eliminate all-local service at these stations.[62] As part of service cuts on September 30, 1990, the R was cut back to 71st Avenue outside of rush hours. Local service to 179th Street was replaced by F trains, which provided Queens Boulevard Express service during middays, evenings, and weekends, and local G service during late nights.[63]

In May 1989, Sunday headways were reduced from twelve minutes to ten minutes.[56] As part of the changes, on October 1, 1990, morning rush hour service from 179th Street was discontinued, and all E trains began running to Jamaica Center.[64] In addition, the frequency of E service was reduced from 15 trains per hour to 12 trains per hour to allow the frequency of F service to be increased from 15 trains per hour to 20 trains per hour. The frequency of F service was subsequently reduced to running every 3+1⁄2 minutes on April 15, 1991, before being increased back to 3+1⁄3 minutes, or about 18 trains per hour, on October 26, 1992.[20] On April 1, 1991, E trains were shortened to run with six-car trains between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m. in order to increase passenger security during overnight hours.[65][66]

In 1992, the MTA considered three options to improve service at the local stops east of 71st Avenue, including leaving service as is, having E trains run local east of 71st Avenue along with R service, and having F trains run local east of 71st Avenue replacing R service, which would be cut back to 71st Avenue at all times. The third option was chosen to be tested for six months starting in October or November 1992.[67] The test started on October 26, 1992, and was implemented on a permanent basis six months later, eliminating express service along Hillside Avenue.[68][62]

63rd Street changes

On March 23, 1997, the E service began stopping at 75th Avenue and Briarwood during evenings, nights and weekends.[69] On August 30, 1997, E service began running local in Queens during late nights in order to ease connections, reduce the need for late night transfers, and provide even service intervals.[70] On the same date, late night G service was permanently cut back from 179th Street to Court Square, replaced by F service running local east of Queens Plaza, doubling late night service frequency at Queens Boulevard local stations.[71][72] On September 8, 1998, E trains began running at a frequency of eight trains per hour middays, an increase from six trains per hour.[7]

During the early part of 2000, because of the replacement of track switches at the World Trade Center station, the E was extended to Euclid Avenue at all times except late nights, when it operated to Canal Street.[73] Service on the E was again affected by the September 11 attacks in 2001, as its terminal station, World Trade Center, was located at the northeastern corner of the World Trade Center site, so for a time, the E again operated to Euclid Avenue in Brooklyn as the local on the IND Fulton Street Line at all times except late nights, replacing the temporarily suspended C service. On September 24, 2001, C service was restored, and E service was cut back to Canal Street, since World Trade Center would be closed until January 28, 2002.[74]

On December 16, 2001, the connection from the IND 63rd Street Line to the Queens Boulevard Line opened, and F trains were rerouted via this connector to travel between Manhattan and Queens.[75][76] E rush hour service was increased from 12 trains per hour to 15 trains per hour, and F service decreased from 18 trains per hour to 15 trains per hour to accommodate these trains. These trains ran to 179th Street, running express along Hillside Avenue, due to a lack of capacity to handle additional trains at Jamaica Center. Four trains began at 179th Street in the morning rush hour, and three began there in the beginning of the evening rush hour, four rush hour E trains ran to 179th Street in the evening rush hour, and three morning rush hour reverse-peak trips terminated at Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike.[20][77] In addition, the frequency of weekday evening service was increased, with trains running every ten minutes instead of every 12 minutes.[78]

In 2002, the frequency of weekend E service was increased. Trains began running every eight minutes on Saturday mornings, instead of every ten minutes, and every ten or twelve minutes on Saturday evenings, instead of every twelve minutes. Sunday service was increased to run every ten or twelve minutes during the morning and evening, instead of every twelve or fifteen minutes, and trains began running every 8 or 10 minutes during afternoons, instead of every twelve minutes. On April 27, 2003, evening service was increased, with trains running at six-, eight-, and ten-minute headways, instead of twelve-minute headways. Midday, afternoon, and early evening service was increased to run every eight minutes on February 22, 2004.[7] On September 16, 2019, the three trips that terminated at Kew Gardens were extended to 179th Street, making express stops along Hillside Avenue.[79]

Between September 19 and November 2, 2020, E service was cut back to Jamaica–Van Wyck due to track replacement on the upper levels of the Jamaica Center and Sutphin Boulevard stations. During this time, a shuttle bus connected to Sutphin Boulevard and Jamaica Center.[80][81] During the second phase, which started on November 2, 2020, a limited number of E trains ran to Jamaica Center, running express east of 71st Avenue during the day on weekdays and making local stops at other times. Service to 179th Street was expanded from weekday limited rush hour service to weekday daytime service; these trains made local stops east of 71st Avenue.[82] This phase was completed in December 2020.[83]

On March 17, 2023, New York City Transit made adjustments to evening and late night E, F and R service to accommodate long-term CBTC installation on the Queens Boulevard Line between Union Turnpike and 179th Street. E service originating from the World Trade Center began operating local in Queens two hours earlier on weekdays and Saturdays, after 9:30 pm instead of 11:30 pm, and one hour earlier on Sundays, after 9:30 pm instead of 10:30 pm.[84] Starting on August 28, 2023, E service to 179th Street was temporarily suspended; this service change is planned to continue through the first quarter of 2024.[85]

EE service

.svg.png.webp)

The EE originally ran as an Eighth Avenue local between 71st Avenue and Chambers Street during off peak hours when the GG did not run.[18][86] This service was discontinued on July 1, 1937.[6] However, the EE reappeared on November 27, 1967, when it ran between 71st–Continental Avenues and Whitehall Street via the local tracks of the BMT Broadway Line, replacing the RR.[52][87] This service was discontinued on August 30, 1976, and replaced by the N.[53][88]

Issues

Overcrowding

The E and F, the two Queens Boulevard express services, have historically been some of the most overcrowded routes in the entire subway system, and have more ridership than can be accommodated by existing capacity.[89][90][91] Multiple efforts have been made to deal with the problem. In 1968, as part of the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority (MCTA)'s Program for Action plan to drastically expand the region's transportation network, the 63rd Street–Southeast Queens line was proposed to increase capacity between Queens and Manhattan and reduce overcrowding on Queens Boulevard express trains.[92][93][94] This line would have served as a "super-express" bypass of the Queens Boulevard Line, paralleling the line by running along the Long Island Rail Road's Main Line, and making stops at Northern Boulevard, where a transfer would be available to Queens Plaza, and Woodside, before merging with the Queens Boulevard Line at 71st Avenue. The line would have provided additional express service to stations east of 71st Avenue, and was intended to divert passengers from the overcrowded E and F to the new line, which would have connected to the BMT Broadway Line and IND Sixth Avenue Lines in Manhattan via the new 63rd Street Lines.[95][96] Since funding for the entire line dried up because of the 1975–1976 New York City fiscal crisis,[97]: 236 the plan was scaled back to the construction of the 63rd Street Lines to a dead-end station at 21st Street–Queensbridge in Queens.[98][99]

In 1990, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) elected to connect the 63rd Street Lines to the Queens Boulevard Line at 36th Street, with connections to both the local and express Queens Boulevard tracks.[100][101] In 2001, the 63rd Street Connection was completed, allowing for an increase of nine trains per hour on the line between Queens and Manhattan through the introduction of V service.[102] Express F trains, which had run via 53rd Street, were rerouted via the new connection, and were replaced by new local V trains.[103] To further increase capacity, as part of the MTA's 2010–2014 Capital Program the MTA is equipping the tracks from 50th Street/8th Avenue and 47th–50th Streets–Rockefeller Center to Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike with communications-based train control,[104] which would allow for three more trains during peak hours on the Queens Boulevard express tracks (it currently runs 29 tph). This would also increase capacity on the local tracks of the IND Queens Boulevard Line.[105][106] With the installation of CBTC on the Eighth Avenue Line as part of the 2015–2019 Capital Program, and on the Archer Avenue Line as part of the 2020–2024 Capital Program, the E will become fully automated.[107][108]: 23

In October 2017, twenty five-car train sets assigned to the E service had seats at the end of the cars removed to provide extra capacity.[109][110] The MTA expected that the removal of seats would allow each E train to carry up to 100 additional riders.[91] Subsequent surveys found that the removal of seats improved passenger flow on trains, helping reduce dwell times in stations.[111]

Homelessness

For several decades,[112] the E has hosted a large population of homeless people and has been nicknamed the "Homeless Express", according to a conductor interviewed by WNBC.[113] It is the subway route that most homeless people sleep on since the route runs fully underground, sheltering people from the cold, and since the route has some of the system's newer rolling stock.[113][114] In addition, the route passes through major transit hubs that shelter the homeless, like Pennsylvania Station and the Port Authority Bus Terminal.[115]

Route

Service pattern

E trains run between Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer on the Archer Avenue Line and World Trade Center on the Eighth Avenue Line at all times, running via the Queens Boulevard Line in Queens. E trains run local along the Eighth Avenue Line at all times. All trains run express in Queens between 71st Avenue and Queens Plaza at all times except late nights, when they make local stops. On weekends, weekday evenings, and late nights, E trains stop at 75th Avenue and Briarwood; limited AM-rush trains also make these stops in both directions.[116][117]

E trains share tracks with F trains between the 75th Avenue and 36th Street interlockings during weekday rush hours and middays, and between the Van Wyck Boulevard and 36th Street interlockings on evenings, late nights and weekends. The shared segment with the F, during rush hours, receives the most scheduled service of any track segment in the system with 30 trains per hour, 15 on the E, and 15 on the F. The route shares tracks with M trains between Queens Plaza and Fifth Avenue–53rd Street, and with C or late-night A service from 42nd Street–Port Authority Bus Terminal to Canal Street.[118]: 4 [119]: 28 [120]

The following table shows the lines used by the E service, with shaded boxes indicating the route at the specified times:[121]

| Line | From | To | Tracks | Times | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rush hours | weekdays | evenings, weekends | late nights | ||||

| IND Archer Avenue Line (full line) | Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer | Jamaica–Van Wyck | all | Most trains | |||

| IND Queens Boulevard Line (full line) | Jamaica–179th Street | Sutphin Boulevard | express | Limited service (suspended) | — | — | — |

| local | Very limited service (suspended) | ||||||

| Briarwood | 75th Avenue | express | Most trains | ||||

| local | Limited service | ||||||

| Forest Hills–71st Avenue | Queens Plaza | express | |||||

| local | |||||||

| Court Square–23rd Street | Seventh Avenue | all | |||||

| IND Eighth Avenue Line | 50th Street | World Trade Center | local | ||||

Stations

For a more detailed station listing, see the articles on the lines listed above.[3] As of August 2023, the branch to Jamaica–179th Street is suspended until early 2024.[85]

| Station service legend | |

|---|---|

| Stops all times | |

| Stops all times except late nights | |

| Stops late nights only | |

| Stops weekdays during the day | |

| Stops rush hours in the peak direction only | |

| Station closed | |

| Stops rush hours only (limited service not noted on map) | |

| Stops evenings, late nights, and weekends | |

| Time period details | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act | |

| Station is compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act in the indicated direction only | |

| Elevator access to mezzanine only | |

JC |

179th |

Stations | Subway transfers | Connections/Other Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queens | |||||||

| Hillside Avenue Branch (limited rush hour service only) | |||||||

| — | Jamaica–179th Street | F |

Q3 bus to JFK Int'l Airport | ||||

| 169th Street | F |

Q3 bus to JFK Int'l Airport Two p.m. rush-hour trains to Jamaica–179th Street stop here[122] | |||||

| Parsons Boulevard | F |

||||||

| Sutphin Boulevard | F |

Q44 Select Bus Service Two p.m. rush-hour trains to Jamaica–179th Street stop here[122] | |||||

| Archer Avenue Branch | |||||||

| — | Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer | J |

Q44 Select Bus Service | ||||

| Sutphin Boulevard–Archer Avenue–JFK Airport |

J |

LIRR City Terminal Zone at Jamaica AirTrain JFK Q44 Select Bus Service | |||||

| Jamaica–Van Wyck | |||||||

| Queens Boulevard Line (services from 179th Street and Jamaica Center merge) | |||||||

| Briarwood | F |

Q44 Select Bus Service Two p.m. rush-hour trains to Jamaica–179th Street stop here[122] | |||||

| Kew Gardens–Union Turnpike | F |

Q10 bus to JFK Int'l Airport | |||||

| 75th Avenue | F |

Two p.m. rush-hour trains to Jamaica–179th Street stop here[122] | |||||

| Forest Hills–71st Avenue | F |

LIRR City Terminal Zone at Forest Hills | |||||

| | | 67th Avenue | F |

|||||

| | | 63rd Drive–Rego Park | F |

Q72 bus to LaGuardia Airport | ||||

| | | Woodhaven Boulevard | F |

Q52/Q53 Select Bus Service | ||||

| | | Grand Avenue–Newtown | F |

Q53 Select Bus Service | ||||

| | | Elmhurst Avenue | F |

Q53 Select Bus Service | ||||

| Jackson Heights–Roosevelt Avenue | 7 F |

Q47 bus to LaGuardia Airport Marine Air Terminal Q53 Select Bus Service Q70 Select Bus Service to LaGuardia Airport | |||||

| | | 65th Street | F |

|||||

| | | Northern Boulevard | F |

|||||

| | | 46th Street | F |

|||||

| | | Steinway Street | F |

|||||

| | | 36th Street | F |

|||||

| Queens Plaza | F |

Q94/Q95 F train shuttle buses | |||||

| Court Square–23rd Street | F G 7 |

Station is ADA-accessible in the southbound direction only | |||||

| Manhattan | |||||||

| Lexington Avenue–53rd Street | 4 F |

||||||

| Fifth Avenue/53rd Street | F |

||||||

| Seventh Avenue | B |

||||||

| 50th Street | A |

Station is ADA-accessible in the southbound direction only | |||||

| Eighth Avenue Line | |||||||

| 42nd Street–Port Authority Bus Terminal | A 1 7 N S at Times Square–42nd Street B |

Port Authority Bus Terminal M34A Select Bus Service | |||||

| 34th Street–Penn Station | A |

M34/M34A Select Bus Service Amtrak, LIRR, NJ Transit at Pennsylvania Station | |||||

| 23rd Street | A |

M23 Select Bus Service | |||||

| 14th Street | A L |

M14A/D Select Bus Service | |||||

| West Fourth Street–Washington Square | A B |

PATH at Ninth Street | |||||

| Spring Street | A |

||||||

| Canal Street | A |

||||||

| World Trade Center[lower-alpha 2] | A 2 N |

PATH at World Trade Center NY Waterway at Brookfield Place | |||||

Route bullet

The E is signed on trains, in stations, and on maps with a blue emblem, or "bullet" since it runs via the Eighth Avenue Line.[124] The route was first color-coded in a light blue on November 26, 1967, when the NYCTA introduced its first set of colored service labels to coincide with the opening of the Chrystie Street Connection.[125]: 35 [126] In June 1979, the route was given a darker blue bullet as part of the introduction of a new color-coding scheme based on subway trunk lines in Manhattan, done in connection with a redesign of the subway map.[125]: 76, 80–81 [127]

Rolling stock

The E train uses ten-car R160 trains to provide regular service, and uses 260 R160 cars, or 26 trains, to provide weekday service. E trains share their rolling stock with the F, G, and R trains, and the route's rolling stock is stored and maintained at Jamaica Yard.[120]

Notes

- ↑ During weekday rush hours and middays, most E trains skip 75th Avenue and Briarwood; at all other times, E trains serve the two stops.[3]

- ↑ Chambers Street–World Trade Center are actually counted as two separate stations by the MTA. The E train terminates at World Trade Center while the A and C trains have through service at Chambers Street.[123]

References

- ↑ 'Subdivision 'B' Car Assignment Effective December 19, 2021'. New York City Transit, Operations Planning. December 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Subdivision 'B' Car Assignments: Cars Required November 1, 2021" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 64 (12): 3. December 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "E Subway Timetable, Effective December 4, 2022". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ "New Subway Links Running Smoothly; Exact Schedules Maintained on First Day's Operation of Queens Tubes". The New York Times. August 20, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Two Subway Units Open at Midnight; Links in City-Owned System in Queens and Brooklyn to Have 15 Stations. Trains Tested on Routes Full Staffs Operate Them on Schedule Minus Passengers – Celebrations Planned". The New York Times. August 18, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Linder, Bernard (October 1968). "Independent Subway Service History" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 11 (5): 3–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Linder, Bernard (January 2011). "E Headways" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 54 (1): 2–3.

- 1 2 Oszustowicz, Eric (March 2006). "A History of the R-1 to R-9 Passenger Car Fleet" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 49 (3).

- 1 2 "IND Extended to Queens 70 Years Ago" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 46 (8): 1. August 2003.

- ↑ "La Guardia Opens New Subway Link; Warmly Praises Delaney as He Puts $17,300,000 Line on East Side Into Service. Seeks Wider Home Rule Hints at Ceremony That City Will Again Attempt to End Transit Board's Powers. The Mayor Opens a New Line of the City Subway System. La Guardia Opens New Subway Link". The New York Times. January 2, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Two Subway Links Start Wednesday; City Will Begin Operating Fulton Street Line and Extension to Jay Street. Mayor to Make Trip Entire System With Exception of Sixth Av. Route to Be Finished Early Next Year". The New York Times. April 6, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ "PWA Party Views New Subway Link: Queens Section to Be Opened Tomorrow Is Inspected by Tuttle and Others" (PDF). The New York Times. December 30, 1936. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ↑ "City Subway Opens Queens Link Today; Extension Brings Kew Gardens Within 36 Minutes of 42d St. on Frequent Trains". The New York Times. December 31, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Subway Link Opens Soon: City Line to Jamaica Will Start About April 24" (PDF). The New York Times. March 17, 1937. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Trial Run to Jamaica on Subway Tomorrow: Section From Kew Gardens to 169th Street Will Open to Public in Two Weeks" (PDF). The New York Times. April 9, 1937. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Trains Testing Jamaica Link Of City Subway". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 10, 1937. p. 3. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Jamaica Will Greet Subway". The New York Sun. April 23, 1937. p. 8. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "New Subway Link to Jamaica Opened; La Guardia, City Officials and Civic Groups Make Trial Run on 10-Car Train". The New York Times. April 25, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Transit Link Open Today; 8th Ave. Line Extended to Jamaica—Celebration Arranged". The New York Times. April 24, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Linder, Bernard (December 2010). "E Service Changes" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 53 (12): 2–3.

- 1 2 Linder, Bernard (June 2009). "Houston Street and Smith Street Subways" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 52 (6): 3.

- ↑

- "Subway Station Opens Aug. 28" (PDF). The New York Times. August 5, 1939. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Ely Subway Stop To Open; Queens Station on City-Owned Line Begins Service Tomorrow" (PDF). The New York Times. August 26, 1939. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ↑ "How to Get To The Fair Grounds; by Subway". The New York Times. April 30, 1939. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ "New Subway Spur Is Ready to Open: First Train to Start Four Minutes Before the Fair Officially Begins". The New York Times. April 17, 1939. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ "The New Subway Routes". The New York Times. December 15, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ Report including analysis of operations of the New York City transit system for five years, ended June 30, 1945. New York City: Board of Transportation of the City of New York. 1945. hdl:2027/mdp.39015020928621.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Linder, Bernard (December 1968). "Independent Subway Service History Part II" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 11 (12): 3.

- ↑ "IND Faster Service Will Start Sunday" (PDF). The New York Times. October 20, 1949. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ↑ "New Subway Link Opening in Queens" (PDF). The New York Times. December 12, 1950. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ↑ "Subway Link Opens Monday" (PDF). The New York Times. December 6, 1950. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ↑ Ingalls, Leonard (August 28, 1953). "2 Subway Lines to Add Cars, Another to Speed Up Service" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Bronx to Coney Ride In New Subway Link" (PDF). The New York Times. October 18, 1954. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ↑ Freeman, Ira Henry (June 28, 1956). "Rockaway Trains to Operate Today" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Linder, Bernard (July 2006). "Rockaway Service" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 49 (7): 2–6.

- ↑ Linder, Bernard (July 2016). "60 Years of Subway Service to the Rockaways" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 59 (7): 1.

- 1 2 3 Linder, Bernard (August 2007). "Fulton Street Subway – A, E, CC, and C Service" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 50 (8): 2.

- ↑ ERA Headlights. Electric Railroaders' Association. 1956.

- ↑ "16-Point Plan Can Give Boro Relief NOW". Long Island Star–Journal. August 10, 1962. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ Marks, Seymour (January 21, 1961). "IND Subway Could Use 11-Car Trains" (PDF). Long Island Star-Journal.

- ↑ "IND Fulton St" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 2 (4): 2. September 1959.

- ↑ "Some "E" Trains Were Extended To Lefferts Boulevard". The New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 3 (2): 1. June 1960 – via Issu.

- ↑ ""E" Expresses To Lefferts Blvd". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. June 1960. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ↑ "Comments On NYS Department of Transportation's Report Review of MTA's New Routes Priorities November 1977" (PDF). New York City Transit Authority Engineering department. March 17, 1978. pp. 17–18. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "E Trains to Stop On Lower Level". New York Daily News. March 21, 1970. p. 207. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Another Transit Improvement... E Train Riders 42nd Street Station". New York City Transit Authority. 1970 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ "Queens IND Service Cut; New Switches; New Transfer Passageway" (PDF). The Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 14 (4): 8. August 1971.

- ↑ "To serve you better... ....On E and F Trains in Queens and Manhattan". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. 1972. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Subway Schedules In Queens Changing Amid Some Protest". The New York Times. January 2, 1973. p. 46. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Changes Set for Jan. 2 Praised" (PDF). The New York Times. November 25, 1972. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ "To serve you better... Changes in subway service will become effective 6 AM Tues, Jan. 2". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. 1972. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Improved Service Begins Sept 11". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. 1972. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- 1 2 Fischler, Stan; Friedman, Richard (May 23, 1976). "Subways" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- 1 2 "Service Adjustment on BMT and IND Lines Effective 1 A.M. Monday, Aug. 30". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. August 1976. Retrieved October 23, 2016.

- ↑ Cosgrove, Vincent (January 28, 1977). "Straphangers: Mini-Train Idea Comes Up Short". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Archer Avenue Corridor Transit Service Proposal. New York City Transit Authority, Operations Planning Department. August 1988

- 1 2 3

- Annual Report on 1989 Rapid Routes Schedules and Service Planning. New York City Transit Authority, Operations Planning Department. June 1, 1990. p. 39.

- ↑ Johnson, Kirk (December 9, 1988). "Big Changes For Subways Are to Begin". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ↑ Alternatives Analysis/Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Queens Subway Options Study. United States Department of Transportation, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Urban Mass Transit Administration. May 1990. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Polsky, Carol (December 11, 1988). "New Subway Line Finally Rolling Through Queens". Newsday.

- ↑ "Archer Avenue Extension Opens December 11". Welcome Aboard: Newsletter of the New York City Transit Authority. New York City Transit Authority. 1 (4): 1. 1988.

- ↑ "Archer Opens Dec. 11 Excerpts From TA Plan". Notes from Underground. Committee For Better Transit. 18 (11, 12). January–February 1988.

- 1 2 "Service Change Monitoring Report Six Month Evaluation of F/R Queens Boulevard Line Route Restructure" (PDF). www.laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. April 1993. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ↑ "Service Changes September 30, 1990" (PDF). subwaynut.com. New York City Transit Authority. September 30, 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ↑ Siegel, Joel (September 28, 1990). "We will be missing some trains, sez TA". New York Daily News. p. 7. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ↑

- "Riders' Guide To Reduced Train Lengths". Flickr.com. New York City Transit Authority. 1991. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Riders' Guide To Reduced Train Lengths". Flickr.com. New York City Transit Authority. 1991. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Subway Train Lengths Adjusted to Match Riding" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 34 (11): 1, 5. November 1991.

- ↑ "Van Wyck Blvd Station" (PDF). www.laguardiawagnerarchive.lagcc.cuny.edu. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 1992. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ↑ "October 1992 New York City Subway Map". Flickr. New York City Transit Authority. October 1992. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ↑ "March 1997 New York City Transit Subway Map". Flickr.com. New York City Transit. March 23, 1997. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ↑ May 1997 NYC Transit Committee Agenda. New York City Transit. May 15, 1997. p. 161, 162–163, 164–165.

- ↑ "Starting August 30, there will be changes in late-night service along Queens Boulevard". New York Daily News. September 2, 1997. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Review of the G Line" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 10, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ↑ Donohue, Pete (January 21, 2000). "C you later, riders told Track work will shut Eighth Ave. line". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ↑ "WTC subway stop on E train line reopens". The Journal News. White Plains, New York. January 29, 2002. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ↑ Kershaw, Sarah (December 17, 2001). "V Train Begins Service Today, Giving Queens Commuters Another Option". The New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ↑ See:

- "The Opening of the New 63 St Connector New Routes More Options Less Crowding". thejoekorner.com. New York City Transit. November 2001. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- "The Opening of the New 63 St Connector". thejoekorner.com. New York City Transit. November 2001. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ↑ 63rd Street Connection Operating Guide. New York City Transit. 2001. pp. I–1.

- ↑ "63rd Street Connector In Service – New Schedules in Effect" (PDF). New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders' Association. 45 (1): 13. January 2002.

- ↑ ""B" Division File No. E-1071 S-135 Fall 2019 Daily Timetable In Effect: MTA New York City Transit "E" Line: Queens Blvd – 8 Ave". New York City Transit. September 16, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ↑ "Press Release – NYC Transit – MTA to Perform Critical Track Replacement Work at End of E Line in Queens Next Month". MTA. August 17, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ Pozarycki, Robert (August 28, 2020). "Two Queens meetings on major track work at end of E line in Jamaica". amNewYork. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Jamaica E Track Reconstruction". Jamaica Track Reconstruction. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ↑ "MTA to begin final phase of critical track replacement work in Queens next month". Railway Track and Structures. June 6, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ↑ "MTA to Perform CBTC Signal Installation Work on E, F and R Lines in Queens Starting March 17". MTA.info. New York City Transit. February 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- 1 2 "F and M line service changes starting August 28". MTA. August 28, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ↑ Danzig, Allison (September 7, 1939). "International Array of Stars Ready for Opening of U.S. Title Tennis Today; Four Australians Stay for Tourney Quist, Bromwich, Hopman and Crawford Get Permission to Play at Forest Hills Riggs Among Favorites Hopes to Avenge Setback in Davis Cup Event—British Women to Seek Honors". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Perlmutter, Emanuel (November 16, 1967). "Subway Changes To Speed Service: Major Alterations in Maps, Routes and Signs Will Take Effect Nov. 26" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Burks, Edward C. (August 14, 1976). "215 More Daily Subway Runs Will Be Eliminated by Aug. 30". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ↑ Carroll, Maurice (June 15, 1979). "Serious Subway Crowding Likely as Result of Decision". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ Purdum, Todd S. (February 11, 1994). "Federal Transit Aid Is Intended to Ease Crowded Subways". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- 1 2 Barron, James (October 17, 2017). "The Answer for Standing-Room-Only Subways? More Standing Room". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Full text of "Metropolitan transportation, a program for action. Report to Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor of New York."". Internet Archive. November 7, 1967. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Regional Transportation Program". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 1969. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ↑ Raskin, Joseph B. (2013). The Routes Not Taken: A Trip Through New York City's Unbuilt Subway System. New York, New York: Fordham University Press. doi:10.5422/fordham/9780823253692.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-82325-369-2.

- ↑ Erlitz, Jeffrey (February 2005). "Tech Talk". New York Division Bulletin. Electric Railroaders Association. 48 (2): 9–11. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ↑ Queens Subway Options Study, New York: Environmental Impact Statement. United States Department of Transportation, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, Urban Mass Transit Administration. May 1984. pp. 83–. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ↑ Danielson, M.N.; Doig, J.W. (1982). New York: The Politics of Urban Regional Development. Lane Studies in Regional Government. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90689-1. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Andelman, David A. (October 11, 1980). "Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, Won't Be Used" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 25. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ↑ "New York City Transit 63rd Street-Queens Boulevard Connection-New York City – Advancing Mobility – Research – CMAQ – Air Quality – Environment – FHWA". www.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ Final Environmental Impact Statement for the 63rd Street Line Connection to the Queens Boulevard Line. Queens, New York, New York: Metropolitan Transportation Authority, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. June 1992. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ La Guardia International Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Airport Access Program, Automated Guideway Transit System (NY, NJ): Environmental Impact Statement. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, New York State Department of Transportation. June 1994. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (December 15, 2000). "Plan Would Put Extra Trains On Busy Lines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy (July 9, 2002). "Tunnel Vision; When One New Train Equals One Less Express". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting: July 2015" (PDF). New York City: Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2015. pp. 37–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ↑ Vantuono, William C. (August 27, 2015). "Siemens, Thales land NYCT QBL West Phase 1 CBTC contracts". Railway Age. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ↑ "MTA 2010–2014 Capital Program Questions and Answers" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. pp. 11–12. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ↑ "MTA Moves Forward with Signal Modernization of Eighth Avenue ACE Line". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 13, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Transform the Subway" (PDF). Fast Forward. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ Chung, Jen (October 3, 2017). "Photos: Step Inside The MTA's New Subway Cars, Now With Less Seating". Gothamist. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Subway Action Plan Update: New Subway Cars on E Line". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 3, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ↑ NYCTRC Meeting July 23, 2020. Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA. August 24, 2020. Event occurs at 1:24:22. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ↑ Correal, Annie (January 14, 2018). "As Homeless Take Refuge in Subway, More Officers Are Sent to Help". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- 1 2 Cheng, Pei-Sze; Pavlovic, Kristina (February 13, 2018). "MTA Conductors Spill Secrets of the NYC Subway System". NBC New York. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ Verhovek, Sam Howe (November 21, 1988). "For Shelter, Homeless Take the E Train". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ Correal, Annie (January 8, 2018). "In Deepest Cold, a Subway Car Becomes the Shelter of Last Resort". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "6:39 AM – 7:29 AM Jamaica Center-Parsons/Archer – OpenMobilityData". transitfeeds.com. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ↑ "5:53 AM – 6:40 AM World Trade Center – OpenMobilityData". transitfeeds.com. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Review of F Line Operations, Ridership, and Infrastructure" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 7, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Review of the A and C Lines" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 11, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Dougherty, Peter (2006) [2002]. Tracks of the New York City Subway 2006 (3rd ed.). Dougherty. OCLC 49777633 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Subway Service Guide" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "6:40 PM – 7:28 PM Jamaica-179 St – OpenMobilityData". transitfeeds.com. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Station Complexes". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. May 28, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Line Colors". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- 1 2 Lloyd, Peter B.; Ovenden, Mark (2012). Vignelli Transit Maps. RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press. ISBN 978-1-933360-62-1.

- ↑ New York City Transit Authority Graphic Standards Manual (PDF). New York: Unimark International. 1970. pp. 25, 51.

- ↑ Navigating New York. 9 Oct 2018-9 Sep 2019, New York Transit Museum, New York.