| Esopus Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Iroquois Confederacy | Esopus tribe of Lenape Indians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Martin Cregier | Chief Papequanaehen | ||||||

The Esopus Wars were two conflicts between the Esopus tribe of Lenape Indians (Delaware) and New Netherlander colonists during the latter half of the 17th century in Ulster County, New York. The first battle was instigated by settlers; the second war was the continuation of a grudge on the part of the Esopus tribe.[1]

Background

Before European colonization, the Kingston area was inhabited by the Esopus people, a Lenape tribe which was estimated to number around 10,000 people living in small village communities by 1600.[2]

In 1609, Henry Hudson explored the river which was named after him, leading to the first contact between the Esopus people and Europeans. Dutch settlers built a factorij (trading post) in Kingston, New York in 1614. The Esopus tribe used the land for farming, and they destroyed the post and drove the settlers back to the south. Colonists established a new settlement in 1652 at Kingston, but the Esopus drove them out again.[3] The settlers returned once again in 1658, as they believed the land to be good for farming. They built a stockade (at 41°56′02″N 74°01′11″W / 41.9338°N 74.0197°W) to defend the village and named the colony Wiltwijck. Skirmishes continued, but the Esopus were not able to repel the settlers, and they eventually granted the land to them.[3]

First Esopus War

The First Esopus War was a short-lived conflict between Dutch settlers and the Esopus Indians from September 20, 1659 and July 15, 1660. An incident occurred where a group of Dutch settlers opened fire on a group of Esopus around a campfire, who had been celebrating with brandy given as payment for farm work. Esopus reinforcements raided Dutch settlements outside the stockade, destroying crops, killing livestock, and burning buildings. The war party later besieged the walled settlement of Wiltwijck.[4]

The colonists were outnumbered and had little hope of winning through force, but they managed to hold out and make some small attacks, including burning the Indians' fields to starve them out. They received reinforcements from New Amsterdam. The war concluded July 15, 1660, when the Indians agreed to trade land for food. Tensions remained between the Esopus and the settlers, however, eventually leading to the second war.[5]

Second Esopus War

Emissaries from the colony contacted the tribe on June 5, 1663 and requested a meeting in hopes of making a treaty. The Esopus replied that it was their custom to conduct peace talks unarmed and in the open, so the settlers kept the gates open into Wiltwijck. The Esopus arrived on June 7 in great numbers, many claiming to be selling produce, thereby infiltrating deep into the town as scouts. Meanwhile, Esopus warriors completely destroyed the neighboring village of Nieu Dorp (Hurley, New York) unbeknownst to the colonists in Wiltwijck.[6] The Esopus scouts had spread themselves around the town and suddenly began their own attack. They took the settlers completely by surprise and soon controlled much of the town, setting fire to houses and kidnapping women before being driven out by the settlers.[5] The attackers escaped, and the settlers repaired their fortifications. On June 16, Dutch soldiers transporting ammunition to the town were attacked on their way from Rondout Creek, but they repelled the Esopus.[7]

Throughout July, colonial forces reconnoitered the Esopus Kill. They were unable to distinguish one tribe from another, and they captured some traders from the Wappinger tribe, one of whom agreed to help them. He gave them information about various Indian forces and served as a guide in the field. In spite of his help, the colonists were unable to make solid contact with the Esopus, who used guerilla tactics and could disappear easily into the woods. After several unproductive skirmishes, the colonists managed to gain the help of the Mohawk, who served as guides, interpreters, and warriors. By the end of July, the colonists had received sufficient reinforcements to march for the Esopus stronghold in the mountains to the north. However, their ponderous equipment made progress slow, and the terrain was difficult. They recognized their disadvantage and burned the surrounding fields in the hope of starving them out, rather than making a direct attack on the Esopus force.

For the next month, scouting parties went out to set fire to the Esopus fields but found little other combat. In early September, another colonial force tried to engage the Esopus on their territory, this time successfully. The battle ended with the death of Chief Papequanaehen and several others. The Esopus fled, and the colonists led by Captain Martin Cregier[8] pillaged their fort before retreating, taking supplies and prisoners. This effectively ended the war, although the peace was uneasy.[7]

Outcome

The Dutch settlers remained suspicious of all Indians with whom they came into contact and expressed misgivings about the intentions of the Wappingers and even the Mohawks, who had helped them defeat the Esopus.[7] Colonial prisoners taken captive by the Indians in the Second Esopus War were transported through regions that they had not yet explored, and they described the land to the colonial authorities who set out to survey it. Some of this land was later sold to French Huguenot refugees who established the village of New Paltz.[1]

In September 1664, the Dutch ceded New Netherland to the English. The English colonies redrew the boundaries of Indian territory, paid for land that they planned to settle, and forbade any further settlement on the established Indian lands without full payment and mutual agreement. The new treaty established safe passage for both settler and Indians for purposes of trading. It further declared "that all past Injuryes are buryed and forgotten on both sides," promised equal punishment for settlers and Indians found guilty of murder, and paid traditional respects to the sachems and their people.[9] Over the course of the next two decades, Esopus lands were bought up and the Indians moved out peacefully, eventually taking refuge with the Mohawks north of the Shawangunk mountains.

References

- 1 2 Smith, Jesse J. (2005-05-29). "Esopus Indian wars were 'the clash of cultures'". Daily Freeman. Kingston, NY. Archived from the original on 2012-09-08. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ David Levine (2021-07-28). "Discover the Hudson Valley's Native American History". Hvmag.com. Archived from the original on 2017-05-24. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- 1 2 Sylvester, Nathaniel Bartlett (1880). History of Ulster County, New York, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia, PA: Everts & Peck. OCLC 2385957.

- ↑ "Esopus Indian wars were 'the clash of cultures' – Daily Freeman". Dailyfreeman.com. 29 May 2005. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- 1 2 Smith, Philip H. (1887). "The First Esopus War". Legends of the Shawangunk. Pawling, NY: Smith & Company. OCLC 447759526.

- ↑ Baker, David (2006). "A Brief History of Hurley". Archived from the original on August 22, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Krieger, Martin (1663). "Journal of the Esopus War 1663". Journal of the Second Esopus War (PDF). Hudson River Valley Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Otto, Paul (2006). The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley. Berghahn Books. p. 152. ISBN 1-57181-672-0.

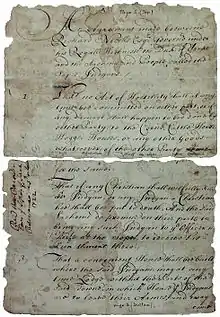

- ↑ Ulster County Clerk (2002). "Richard Nicolls Esopus Indian Treaty" (PDF).

The definitive and most detailed history of the Esopus Indian Wars (First Esopus War and Second Esopus War, as they're known) can be found in chapters 3-6 of The Early History of Kingston & Ulster County, N.Y. by Marc B. Fried (published 1975). This book is still in print.