| Edinburgh town walls | |

|---|---|

| Edinburgh, Scotland | |

Remains of the bastion known as the 'Flodden Tower' with Edinburgh Castle behind and the Telfer Wall on the right | |

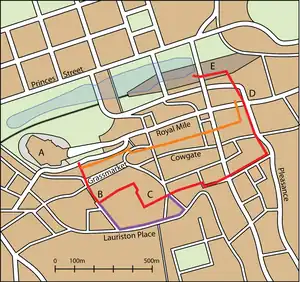

Map showing the town walls, overlaid on the present-day streets Key: Orange: King's Wall, Red: Flodden Wall, Purple: Telfer Wall A: Edinburgh Castle, B: Flodden Tower, C: Greyfriars Kirkyard; D: site of Netherbow Port, E: Waverley station Blue shading: approximate extent of Nor Loch | |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Some sections remain to full height |

| Site history | |

| Built | 15th to 17th century |

| Materials | Stone |

| Demolished | Parts demolished from mid 18th century |

There have been several town walls around Edinburgh, Scotland, since the 12th century. Some form of wall probably existed from the foundation of the royal burgh in around 1125, though the first building is recorded in the mid-15th century, when the King's Wall was constructed. In the 16th century the more extensive Flodden Wall was erected, following the Scots' defeat at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. This was extended by the Telfer Wall in the early 17th century. The walls had a number of gates, known as ports, the most important being the Netherbow Port, which stood halfway down what is now the Royal Mile. This gave access from the Canongate which was, at that time, a separate burgh.

The walls never proved very successful as defensive structures, and were easily breached on more than one occasion. They served more as a means of controlling trade and taxing goods, and as a deterrent to smugglers.[1] By the mid 18th century, the walls had outlived both their defensive and trade purposes, and demolition of sections of the wall began. The Netherbow Port was pulled down in 1764, and demolition continued into the 19th century. Today, a number of sections of the three successive walls survive, although none of the ports remain.

Background

Edinburgh was formally established as a royal burgh by King David I of Scotland around 1125. This gave the town the privilege of holding a market, and the power to raise money by taxing goods coming into the burgh for sale.[1] It is probable, therefore, that some form of boundary was constructed around this time, although it may have been a timber palisade or ditch, rather than a stone wall.[2]

To the north of Edinburgh lay the Nor Loch, formed in the early 15th century in the depression where Princes Street Gardens are now laid out.[3] This defence was not natural, but was formed by creating a dam and sluice at the foot of Halkerston's Wynd to the east.[4] It was further augmented by the steep slope up to the northern edge of the Old Town.[5] Edinburgh Castle, on its rocky outcrop, defended the western approach. Walls were therefore needed primarily on the south and east sides of the burgh.

Early records mention a west gate in 1180, a south gate in 1214, and the Netherbow Port in 1369.[2] In 1362 the Wellhouse Tower was built beneath the north wall of the castle, protecting the castle's water supply, and defending the approach along the south shore of the Nor Loch.[6]

King's Wall

The King's Wall is first recorded in 1427, in a title deed which refers to the wall as the property boundary.[7] In 1450, King James II issued a charter permitting the burgesses of Edinburgh to defend their town, as follows:

|

|

In a further royal charter of 28 April 1472, King James III ordered the demolition of houses built on or outside the King's Wall, which were hampering efforts to strengthen the defences.[9] Edinburgh was thus one of only three Scottish towns to have medieval stone walls, the others being Stirling and Perth, though other towns had earth walls or palisades.[10]

The early wall had two ports: the Upper Bow or Over-Bow, in the vicinity of what is now Victoria Street, and the Nether Bow,[11] on the present Royal Mile near Fountain Close, which was located near around 46 metres (151 ft) further west than the later structure. In addition, posterns (side gates) were provided, for example at Gray's Close.[12] The alignment of the wall was irregular, as existing property boundaries or walls were reinforced to form a defence.[13]

Archaeological evidence

The wall was thought to have run along the south side of what is now the Royal Mile, above the Cowgate, from the slope of the Castle Hill in the west, almost as far as the modern St Mary's Street in the east, where it turned to cross the High Street.[14] However, excavations in the 2002-2004 by Headland Archaeology in the Cowgate, in advance of a housing development, found what is thought to be remains of the King's Wall. This discovery pushes the southern boundary of the wall significant further south, down on to the Cowgate. This discovery, plus the discovery of a massive fortification ditch at the excavations of St Patrick’s Church has led the archaeologists to believe that large portions of the medieval town defences were situated along the north side of the Cowgate and not halfway up the slope.[15]

Flodden Wall

In 1513, King James IV led an invasion of England in support of the French and the Auld Alliance. On 9 September, the Scots met the English at the Battle of Flodden, and were heavily defeated, with King James killed on the field. An English invasion was widely expected, and in Edinburgh it was resolved to build a new town wall. However, the new wall was also an opportunity to control smuggling into the burgh,[16] and the town council accordingly decided to extend the wall south to take in the Grassmarket and Cowgate areas of the burgh.[2] Construction began the following year, but was not completed until 1560.[14] Work started at the western end, and the final section was the stretch from Leith Wynd to the Nor Loch, incorporating the New Port. The cost of this last work was £4/10s Scots per rood (one rood = six ells or 5.6 metres) for the wall, plus 40s per rood for the battlements.[17]

The Flodden Wall, as it became known, was generally around 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) thick and up to 7.3 metres (24 ft) high.[18] The Flodden Wall began at the south side of the castle, running south across the west end of the Grassmarket, where the West Port was located, and continued uphill along the Vennel. A watch-tower or bastion survives at this, the south-west extent of the wall. It then ran east, wrapping around Greyfriars Kirkyard, to the Bristo Port and the Potterow Port, both located in the vicinity of the National Museum of Scotland. Continuing east, the wall passed the Kirk o' Field, where the Old College now stands, and ran along Drummond Street, turning north at the Pleasance to enclose the former Blackfriars Monastery. The Cowgate Port was located at the foot of the Pleasance. From here, along St Mary's Wynd and Leith Wynd, the town's defences were provided by fortifying the existing houses along the west side of the wynds.[2] At the junction of these wynds, at the Netherbow, the narrowed section of the High Street, stood the Netherbow Port, between the High Street and the Canongate leading to Holyrood Abbey and Holyrood Palace. At Leith Wynd Port (outside the town walls) the wall continued west to the Nor Loch, since replaced at this location by Waverley railway station, terminating at the New Port. The Flodden Wall enclosed an area of just under 57 hectares (140 acres), and remained the limit of the burgh until the 18th century.[19] Contained within this area, in 1560, was a population of around 10,000.[18]

There were six ports in the Flodden Wall. Anti-clockwise from the castle they were:

- West Port, built 1514 at the west end of the Grassmarket,[18] where the modern street of West Port is today, and giving access to Wester Portsburgh;

- Bristo Port (Greyfriars Port, Society Port), built around 1515 on Bristo Street, close to Greyfriars Kirk and the Society of Brewers;[20]

- Potterrow Port (Kirk o' Field Port), at the head of Horse Wynd near the Kirk o' Field, giving access to Easter Portsburgh;[20]

- Cowgate Port (Soo-gate, Blackfriars Port), on the Cowgate near the Blackfriars Monastery, the access to the Grassmarket from the east;

- Netherbow Port, access from the High Street to the Canongate;

- New Port, at the foot of Halkerston's Wynd beneath the modern North Bridge, giving access north to Multrees Hill.

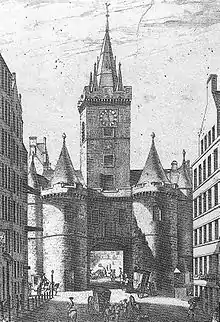

Besides, there were a number of small posterns.[12] The heads and limbs of executed criminals were regularly displayed above the ports.[21] Of the six ports, the Netherbow was the only one which took the form of a large fortified gateway. Repairs to the Netherbow are recorded in 1538,[22] and a drawing of 1544 shows the Netherbow as a wide arched gate flanked by two round towers. In 1571, the gateway between the towers was rebuilt, and a central clock tower was added above the gateway, topped by an octagonal stone spire. This structure was repaired in the early 17th century.[23]

Military action

Although the expected English invasion never materialised after Flodden, the 16th century was a turbulent period in Scotland. In 1544 the Earl of Hertford led an English force into Scotland during the War of the Rough Wooing. On 6 May, having captured Leith, Hertford's men, under the command of Sir Christopher Morris, blew open the Netherbow Port with their artillery. The town was burned over the following three days, "so that neither within the walls nor in the suburbs was left any one house unburnt".[24]

Further disturbances took place during the troubled reign of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1567), and its aftermath. In 1558 the Protestant Lords of the Congregation marched on Edinburgh against the Catholic French Regent, Mary of Guise, and were able to take control of the town without difficulty, despite the guards posted at the city gate.[25] Following the forced abdication of Queen Mary, Scotland's nobility was divided between her supporters, and those of the infant King James VI, represented by a series of regents. Edinburgh was held for the Queen by William Kirkcaldy of Grange, and in May 1571 the town was besieged by the Regent's forces under James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton. Repairs were made to the walls, and the Netherbow was barricaded. Nearby houses were pulled down to improve defences, and the siege gun Mons Meg was employed to batter houses outside the wall which were being used by snipers. Unable to make any headway, the besiegers withdrew on 20 May.[26]

Again the defences were strengthened in September, in advance of a second siege which began on 16 October. By this stage only ten per cent of Edinburgh's inhabitants remained in the city. The besiegers under Regent Mar had only seven guns, and while they did manage to breach the Flodden Wall, the inner defences were too strong for an assault. By 21 October the siege was once again lifted.[27] A blockade of the town was continued until July 1572 when a truce was agreed. Grange retreated into the castle and handed over the town to the Regent's party.[28] The siege of Edinburgh Castle continued until May 1573, when it was finally reduced by a battery of guns shipped from England.[29]

Telfer Wall

In 1618 the town council bought 10 acres (4.0 ha) of land to the west of Greyfriars Kirk, which was enclosed between 1628 and 1636 by the Telfer Wall.[30] Most of this land was subsequently sold to the charitable George Heriot's Trust for the building of George Heriot's Hospital. The rubble-built wall ran south from the Flodden Tower in the Vennel to Lauriston Place; it then turned east, running as far as Bristo Street, where it returned north to the Bristo Port in the Flodden Wall. The Telfer Wall was named after its master mason, John Taillefer.[30]

Later history and demolition

By the 17th century the King's Wall had been almost completely absorbed within later buildings, although it is briefly mentioned in the "Extent Roll", a town survey of 1635, and limited sections appear on James Gordon of Rothiemay's map of 1647.[31] The mason John Mylne and the wright (carpenter) John Scott strengthened the Flodden and Telfer walls and constructed artillery emplacements in 1650.[2] This was due to fear of an English attack on Edinburgh during the English Civil War (nearby Dunbar having been attacked). The quickly made changes included taking the four ornamental tops off the Netherbow Port, in order to install cannon.[32]

Further emplacements were built by Captain Theodore Dury in 1715, in response to the Jacobite rising of that year. In 1736, the lynching of Captain John Porteous by an Edinburgh mob led the British Government in London to impose sanctions on the town. Porteous, Captain of the Town Guard, had been convicted of murder following the shooting of spectators at a public hanging, but following a reprieve, a mob broke into the Tolbooth Jail and executed him. The initial demand by the House of Lords was for the demolition of the Netherbow Port, although this was resisted by the town, and commuted to a fine by the House of Commons.[33] When the town was threatened by the Jacobite rising of 1745, a company of volunteer citizens was raised for the defence of the city, and the mathematics professor Colin Maclaurin advised on improvements to the walls.[34] However, as Bonnie Prince Charlie's troops approached, the town was undermanned and the walls undefended. On the morning of 17 September, a group of Highlanders under Donald Cameron of Lochiel rushed the Netherbow Port as the gates were opened, and Edinburgh was captured without a fight.[35]

Demolitions began soon after the withdrawal of the Jacobite threat in 1746.[36] The bastions of the Telfer Wall along Lauriston Place were demolished in 1762, as they were obstructing traffic. The Netherbow survived until 1764, when it too was removed as an obstruction.[37] The West Port and the Potterow Port were removed in the 1780s.[38] By now, the New Town was under construction, and although smuggling of goods through the city walls was still being punished, complaints about the zealousness of the guards were widely circulated.[36] The Old College of the University of Edinburgh (constructed from 1789), and then the museum in Chambers Street (constructed from 1861, now part of the National Museum of Scotland), were built over sections of the wall around the Potterow Port. Forrest Road was laid out in the 1840s, resulting in the loss of another section of the Telfer Wall.[39] During construction works around the Advocates' Library and Parliament House in 1832 and 1845, fragments of walling were uncovered, which were attributed to the King's Wall.[31] Two sections of the increasingly neglected town wall collapsed in the mid-1850s. In 1854, a large portion of wall (20 feet high and 3–4 feet thick), and the embankment against which it was built fell into Leith Wynd between the High Street and Calton Road. A week later the Dean of Guild ordered the removal of a 150 feet stretch of the wall from that location. In 1856, a lightning strike appears to have been the cause of the collapse of a 40 to 50 feet stretch of the wall enclosing Greyfriars Kirkyard.[40]

Surviving fragments

Nothing remains of Edinburgh's earliest enclosures, and very little of the King's Wall survives, although parts are probably incorporated in later buildings. A section of walling in Tweeddale Court, on the south side of the Royal Mile, may represent part of the eastern wall. This was exposed, identified and recognised as a fortified wall, initially by two labourers working on the renovation and restoration of the old Oliver & Boyd publishers in 1983. Subsequently, this was confirmed by archaeologists and planners and it was not demolished as consented. The height (6 metres (20 ft)), and lack of openings suggest a defensive purpose.[41] Walling in Castle Wynd, north of the Grassmarket, has also been identified with the King's Wall.[12] In 1973, archaeological excavations on the site now occupied by the Radisson Hotel, south of the High Street, uncovered a fragment of wall, which was thought likely to be the King's Wall. There was also evidence of a house adjacent, which had been demolished sometime in the 15th century, presumably in response to James III's order of 1472.[42]

Four sections of the Flodden Wall survive: to the north and south of the Grassmarket; in Greyfriars Kirkyard; and along Drummond Street and the Pleasance. North of the Grassmarket the wall runs alongside Granny's Green Steps and has been incorporated into later buildings, including the former Greyfriars Mission Kirk.[43] Archaeological excavations and surveys between 1998-2001 found that this section of the wall went through three major phases of construction and redevelopment - its initial building; significant rebuilding during the third quarter of the 18th century, when buildings was constructed along Kings Stables Road and the Wall's western face; and the formation of Granny's Green to the west of the Wall in the late 19th century.[44] A line of granite paving across the Grassmarket marks the line of the wall where it was uncovered during construction work in 2008.[45] In the Vennel the last remaining bastion of the town walls survives. The Flodden Tower, as it is sometimes known, comprises two remaining walls with a total length of 17.2 metres (56 ft),[16] pierced by crosslet gunloops and a 19th-century window.[16] Sections of the Flodden Wall can be seen within Greyfriars Kirkyard, adorned with 16th and 17th century tombstones. At the junction of Forrest Road and Bristo Street a line of cobbles and a narrow gap in the later buildings mark the line of the wall.[46] The longest section is in Drummond Street and the Pleasance, where it originally enclosed the Blackfriars Monastery. At the corner of the wall a blocked archway is probably the entrance to a demolished bastion.[2] The site of the Netherbow is marked with an outline of brass blocks at the junction of the High Street and St Mary's Street.[14]

There are two remaining sections of the Telfer Wall. The first runs along Heriot Place from the Flodden Tower, and forms the west boundary of George Heriot's School. The wall along Lauriston Place was demolished in 1762, as the bastions were obstructing traffic. The only remaining section is that forming the south wall of Greyfriars Kirkyard. An inscription on the building at the corner of Teviot Place and Bristo Street reads "1513 Site of Town Wall", although it was the 17th-century Telfer Wall, not the earlier Flodden Wall, which stood on this spot.[47]

The majority of the surviving sections are protected as scheduled monuments: the Flodden Wall at Granny's Green;[43] the Flodden and Telfer Walls at the Vennel and Heriot Place;[16] and the Flodden Wall at Drummond Place and Pleasance.[48] The walling in Tweeddale Court and the sections within Greyfriars Kirkyard are protected as listed buildings.[41][30] The walls also form part of the Edinburgh Old Town World Heritage Site.

Location

| Point | Coordinates (links to map & photo sources) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| King's Wall in Tweeddale Court | 55°57′01″N 3°11′04″W / 55.95021°N 3.18455°W | |

| Flodden Wall at Granny's Green | 55°56′51″N 3°11′53″W / 55.9475°N 3.19798°W | |

| Flodden Tower | 55°56′46″N 3°11′49″W / 55.94622°N 3.19698°W | |

| Flodden Wall in Greyfriars Kirkyard | 55°56′48″N 3°11′36″W / 55.9466°N 3.19332°W | |

| Flodden Wall markers in Forrest Road | 55°56′47″N 3°11′28″W / 55.94643°N 3.19111°W | |

| Flodden Wall at Drummond Street/Pleasance | 55°56′54″N 3°10′56″W / 55.94841°N 3.18236°W | |

| Netherbow Port | 55°57′02″N 3°11′03″W / 55.95065°N 3.1843°W | |

| Telfer Wall at Heriot Place | 55°56′45″N 3°11′46″W / 55.94571°N 3.19602°W | |

| Telfer Wall at Greyfriars Kirkyard | 55°56′43″N 3°11′31″W / 55.94531°N 3.19191°W |

See also

References

- 1 2 Bell, p.7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gifford pp.84–85

- ↑ Fife, p.4

- ↑ Grants Old and New Edinburgh

- ↑ See Miller

- ↑ Fife, pp.180–181

- ↑ Miller (1887)

- ↑ Marwick, pp.70–71

- ↑ Marwick, pp.134–135

- ↑ McWilliam, p.36

- ↑ From the Scots language nether, meaning "lower", and bow, meaning "arch". Dictionary of the Scottish Language Archived 10 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Cullen, p.1

- ↑ Schofield, p.181

- 1 2 3 Catford, p.18

- ↑ "Vol 69 (2017): Discovering the King's Wall: Excavations at 144-166 Cowgate, Edinburgh | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Edinburgh Town Wall, Flodden Wall and Telfer Wall, Heriot Place. SM2901". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ New Statistical Account of Scotland, p.627

- 1 2 3 Potter, p.22

- ↑ Catford, p.20

- 1 2 Coghill, p.13

- ↑ Coghill, p.10

- ↑ Kerr, p.303

- ↑ Kerr, p.304

- ↑ The Earl of Hertford's expedition against Scotland, pp.10–12

- ↑ New Statistical Account of Scotland, p.626

- ↑ Potter, pp.60–65

- ↑ Potter, pp.85–86

- ↑ Potter, pp.105–106

- ↑ Potter, p.135

- 1 2 3 "Greyfriars Churchyard, including monuments, lodge gatepiers, railings and walls. LB27029". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- 1 2 Schofield, p.155–156

- ↑ Grants Old and New Edinburgh volIV p.331

- ↑ Roughhead, pp.126, 129

- ↑ Gibson, p.9

- ↑ Gibson, p.16

- 1 2 Coghill, p.14

- ↑ The clock from the Netherbow was later incorporated into the Dean Gallery. Coghill, pp.14,17

- ↑ Cullen, p.4

- ↑ Cullen, p.17

- ↑ W M Gilbert (ed.), Edinburgh In The Nineteenth Century, J & R Allan Ltd., Edinburgh 1901

- 1 2 "Tweeddale Court, walling to west of court and to south of Tweeddale House, LB29058". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ Schofield, p.160

- 1 2 "Edinburgh Town Wall, Flodden Wall, Johnston Terrace to Grassmarket, SM3012". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ "Vol 10 (2004): Conservation and change on Edinburgh's defences:archaeological investigation and building recording of the Flodden Wall, Grassmarket 1998-2001 | Scottish Archaeological Internet Reports". journals.socantscot.org. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "Grassmarket gives up a forgotten piece of Flodden Wall". The Scotsman. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ "Secret of the setts revealed by group's detective work". The Scotsman. 30 December 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ↑ Cullen, p.13

- ↑ "Edinburgh Town Wall, Flodden Wall, Drummond Street to Pleasance. SM3013". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

Bibliography

- "Edinburgh". New Statistical Account of Scotland. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Blackwood. 1845.

- Anon. (1886). The Earl of Hertford's expedition against Scotland, 1544. E. & G. Goldsmid. OCLC 4240031.

- Bell, D. (2008). Edinburgh Old Town: The Forgotten Nature of an Urban Form. Tholis. ISBN 978-0-9559485-0-3.

- Catford, E. F. (1975). Edinburgh: the story of a city. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-123850-1.

- Coghill, Hamish (2004). Lost Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-309-9.

- Cullen, W. Douglas (1988). The Walls of Edinburgh. Cockburn Association. ISBN 0-9505159-1-4.

- Fife, Malcolm (2001). The Nor Loch: Scotland's Lost Loch. Pentland Press. ISBN 978-1-85821-806-9.

- Gibson, John Sibbald (1995). Edinburgh in the '45. Saltire Society. ISBN 0-85411-067-4.

- Gifford, John; McWilliam, Colin; Walker, David (1984). Edinburgh. The Buildings of Scotland. Penguin. ISBN 014071068X.

- Kerr, Henry F. (1933). "Notes on the Nether Bow Port" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 67: 297–307. doi:10.9750/PSAS.067.297.307. S2CID 257290149.

- McWilliam, Colin (1975). Scottish Townscape. Collins. ISBN 0-00-216743-3.

- Marwick, James David, ed. (1871). Charters and other documents relating to the city of Edinburgh. A. D. 1143-1540. Scottish Burgh Records Society. LCCN 03014481.

- Miller, Peter (1887). "Was the town of Edinburgh an open and defenceless one before 1450?" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 21: 251–265. doi:10.9750/PSAS.021.251.260. S2CID 254528583.

- Neill, Patrick (1829). Notes Relative to the Fortified Walls of Edinburgh.

- Potter, Harry (2003). Edinburgh Under Siege: 1571–1573. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2332-0.

- Roughead, William, ed. (1909). The Trial of Captain Porteous. William Hodge & Co.

- Schofield, John; et al. (1976). "Excavations south of Edinburgh High Street 1973-4" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 107: 155–204. doi:10.9750/PSAS.107.155.241. S2CID 257752758.