The Green Man, also known as a foliate head,[1] is a motif in architecture and art, of a face made of, or completely surrounded by, foliage, which normally spreads out from the centre of the face.[2] Apart from a purely decorative function, the Green Man is primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the cycle of new growth that occurs every spring.

The Green Man motif has many variations. Branches or vines may sprout from the mouth, nostrils, or other parts of the face, and these shoots may bear flowers or fruit. Found in many cultures from many ages around the world, the Green Man is often related to natural vegetation deities. Often used as decorative architectural ornaments, where they are a form of mascaron or ornamental head, Green Men are frequently found in architectural sculpture on both secular and ecclesiastical buildings in the Western tradition. In churches in England, the image was used to illustrate a popular sermon describing the mystical origins of the cross of Jesus.

"Green Man" type foliate heads first appeared in England during the early 12th century deriving from those of France, and were especially popular in the Gothic architecture of the 13th to 15th centuries. The idea that the Green Man motif represents a pagan mythological figure, as proposed by Lady Raglan in 1939, despite its popularity with the lay public, is not supported by evidence.[1][3][4][5]

Types

Usually referred to in art history as foliate heads or foliate masks, representations of the Green Man take many forms, but most just show a "mask" or frontal depiction of a face, which in architecture is usually in relief. The simplest depict a man's face peering out of dense foliage. Some may have leaves for hair, perhaps with a leafy beard. Often leaves or leafy shoots are shown growing from his open mouth and sometimes even from the nose and eyes as well. In the most abstract examples, the carving at first glance appears to be merely stylised foliage, with the facial element only becoming apparent on closer examination. The face is almost always male; green women are rare. Lady Raglan coined the term "Green Man" for this type of architectural feature in her 1939 article The Green Man in Church Architecture in The Folklore Journal.[6] It is thought that her interest stemmed from carvings at St. Jerome's Church in Llangwm, Monmouthshire.[7]

The Green Man appears in many forms, with the three most common types categorized as:

History

In terms of formalism, art historians see a connection with the masks in Iron Age Celtic art, where faces emerge from stylized vegetal ornament in the "Plastic style" metalwork of La Tène art.[10] Since there are so few survivals, and almost none in wood, the lack of a continuous series of examples is not a fatal objection to such a continuity.

The Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore suggests that they ultimately have their origins in late Roman art from leaf masks used to represent gods and mythological figures.[1] A character superficially similar to the Green Man, in the form of a partly foliate mask surrounded by Bacchic figures, appears at the centre of the 4th-century silver salver in the Mildenhall Treasure, found at a Roman villa site in Suffolk, England; the mask is generally agreed to represent Neptune or Oceanus and the foliation is of seaweed.[11]

In his lectures at Gresham Collage, historian and professor Ronald Hutton traces the green man to India, stating "the component parts of Lady Raglan’s construct of the Green Man were dismantled. The medieval foliate heads were studied by Kathleen Basford in 1978 and Mercia MacDermott in 2003. They were revealed to have been a motif originally developed in India, which travelled through the medieval Arab empire to Christian Europe. There it became a decoration for monks’ manuscripts, from which it spread to churches."

Folk musician Mike Harding gave examples of foliate head figures from Lebanon and Iraq dated to the 2nd century in his A Little Book of The Green Man, as well as his website. There are similar figures in Borneo, Nepal, and India. Harding references a foliate head from an 8th-century Jain temple in Rajasthan.[12]

A late 4th-century example of a green man disgorging vegetation from his mouth is at St. Abre, in St. Hilaire-le-grand, France.[13]

11th century Romanesque Templar churches in Jerusalem have Romanesque foliate heads. Harding tentatively suggested that the symbol may have originated in Asia Minor and been brought to Europe by travelling stone carvers.

The tradition of the Green Man carved onto Christian churches is found across Europe, including examples such as the Seven Green Men of Nicosia carved into the facade of the thirteenth century St Nicholas Church in Cyprus.

The motif fitted very easily into the developing use of vegetal architectural sculpture in Romanesque and Gothic architecture in Europe.

Later foliate heads in churches may have reflected the legends around Seth, the son of Adam, according to which he plants seeds in his dead father's mouth as he lies in his grave. The tree that grew from them became the tree of the true cross of the crucifixion. This tale was in The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, a very popular thirteenth century compilation of Christian religious stories, from which the subjects of church sermons were often taken, especially after 1483, when William Caxton printed an English translation of the Golden Legend.[14]

According to Christian author Stephen Miller, author of "The Green Man in Medieval England: Christian Shoots from Pagan Roots" (2022)[15] "it is a Christian/Judaic-derived motif relating to the legends and medieval hagiographies of the Quest of Seth – the three twigs/seeds/kernels planted below the tongue of post-fall Adam by his son Seth (provided by the angel of mercy responsible for guarding Eden) shoot forth, bringing new life to humankind".[16] This notion was first proposed by James Coulter (2006).[17]

Also, an association of the green man image with the incarnation of Christ was suggested to be demonstrated by the expressions on the face: where carved representations of the Virgin Mary appear nearby, the green men are shown with happy expressions.[18]

From the Renaissance onward, elaborate variations on the Green Man theme, often with animal heads rather than human faces, appear in many media other than carvings (including manuscripts, metalwork, bookplates, and stained glass). They seem to have been used for purely decorative effect rather than reflecting any deeply held belief.

Green Man in the presbytery of St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney, ca. twelfth-thirteenth centuries, Norman and Romanesque.

Green Man in the presbytery of St. Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney, ca. twelfth-thirteenth centuries, Norman and Romanesque.

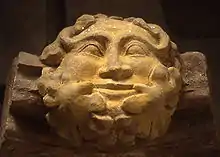

Romanesque sandstone carving, archway in church at Garway, Herefordshire c.13th century

Romanesque sandstone carving, archway in church at Garway, Herefordshire c.13th century A medieval Green Man (disgorging type) on the capital of a column in an English church in Lincolnshire

A medieval Green Man (disgorging type) on the capital of a column in an English church in Lincolnshire "Disgorging type" at Southwell Minster chapter house c. 1300

"Disgorging type" at Southwell Minster chapter house c. 1300

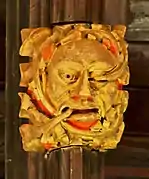

This stone carving of a Green Man from Dore Abbey, Herefordshire, England, retains some of its original colouring.

This stone carving of a Green Man from Dore Abbey, Herefordshire, England, retains some of its original colouring. Medieval misericord; abbey-church of Vendôme, France

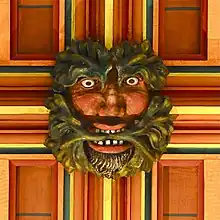

Medieval misericord; abbey-church of Vendôme, France Painted wooden roof boss from Rochester Cathedral, Kent (medieval)

Painted wooden roof boss from Rochester Cathedral, Kent (medieval) This wood carving of a "foliate head" type is on the Renaissance screen at Dore Abbey.

This wood carving of a "foliate head" type is on the Renaissance screen at Dore Abbey.

Carved capital, south door of Maria Laach Abbey, Germany

Carved capital, south door of Maria Laach Abbey, Germany Keystone of the cross vault in the tower chapel of Ligerz, Switzerland

Keystone of the cross vault in the tower chapel of Ligerz, Switzerland

Modern history

In Britain, the image of the Green Man enjoyed a revival in the 19th century, becoming popular with architects during the Gothic revival and the Arts and Crafts era, when it appeared as a decorative motif in and on many buildings, both religious and secular. American architects took up the motif around the same time. Many variations can be found in Neo-gothic Victorian architecture. He was popular amongst Australian stonemasons and can be found on many secular and sacred buildings, including an example on Broadway, Sydney.[19] In 1887 a Swiss engraver, Numa Guyot, created a bookplate depicting a Green Man in exquisite detail. .[20]

In April 2023, a Green Man's head was depicted on the invitation for the Coronation of Charles III and Camilla, designed by heraldic artist and manuscript illuminator Andrew Jamieson. According to the official royal website: "Central to the design is the motif of the Green Man, an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth, to celebrate the new reign. The shape of the Green Man, crowned in natural foliage, is formed of leaves of oak, ivy, and hawthorn, and the emblematic flowers of the United Kingdom."[21][22] which alluded to "the nature worshipper in King Charles" but polarized the public.[5] Indeed, as the medieval art historian Cassandra Harrington pointed out, although vegetal figures were abundant throughout the medieval and early modern period, the foliate head motif is not ‘an ancient figure from British folklore’, as the Royal Household has proclaimed, but a European import.'[3]

In folklore

Citations

- 1 2 3 "foliate head". A Dictionary of English Folklore (Oxford Reference). Retrieved 2023-05-10.

Art historians call this a foliate head; in English over the last twenty years it has been constantly called a Green Man, a term first applied to it by Lady Raglan in 1939, whose authentic meaning was quite different.

- ↑ For the "Lady of Wells" boss in the Chapter House of Wells Cathedral, see Wright, Brian (2011). Brigid: Goddess, Druidess and Saint. The History Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0752472027.

- 1 2 Harrington, Cassandra (6 April 2023). "The truth about King Charles's 'Green Man'". UnHerd.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Livingstone, Josephine (2016-03-07). "The Remarkable Persistence of the Green Man". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- 1 2 Olmstead, Molly (2023-04-08). "Is the Green Man British Enough for the Royal Coronation?". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ↑ Raglan, Lady (March 1939). "The Green Man in Church Architecture". Folklore. 50 (90990): 45–57. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1939.9718148. JSTOR 1257090.

- ↑ "Theories and Interpretations". The Enigma of the Green Man. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ Harding, Mike (1998). A Little Book Of The Green Man. Aurum Press. p. 38. ISBN 1-85410-561-2. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

- ↑ Pesznecker, Susan (2007). Gargoyles: From the Archives of the Grey School of Wizardry. Franklin Lakes NJ: Career Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1-56414-911-4.

- ↑ Sandars, p. 283, "the 'Green Man' peering through hawthorn leaves in the Norwich cloisters and at Southwell is the true descendant of the Brno-Maloměřice heads" (famous bronze Celtic pieces)

- ↑ Illustrated (British Museum highlights:Great dish from the Mildenhall treasure Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ "The Official Mike Harding Web Site". Mikeharding.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ↑ Anderson, William (1990). Green Man. Harpercollins. p. 46. ISBN 0-06-250077-5.

- ↑ Doel, Fran; Doel, Geoff (2013). "The spirit in the tree". The Green Man in Britain. Cheltenham, England: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750953139.

- ↑ Stephen Miller (2022). The Green Man in Medieval England: Christian Shoots from Pagan Roots. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-8411-2.

- ↑ Miller, Stephen (19 April 2023). "The Christian history of the Green Man motif (letter)". The Guardian.

- ↑ Coulter, James (2006). The Green Man Unmasked: A New Interpretation of an Ancient Riddle. Author House. pp. 79–89. ISBN 9781420882865.

- ↑ Simonds, Peggy Muñoz (1995). Iconographic research in English Renaissance literature : a critical guide. New York: Garland Science. p. 321. ISBN 9780824073879.

- ↑ Rose, James (June 7, 2006). "Green Man on Broadway" – via Flickr.

- ↑ Numa Archived 2016-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Guyot Brothers

- ↑ "The Coronation Invitation". The Royal Household. April 19, 2023.

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (5 April 2023). "The coronation invitation reviewed – is Charles planning a pumping pagan party?". The Guardian.

Sources cited

- Basford, Kathleen (1998) [1978]. The Green Man. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0859914970.

- Bramwell, Peter (2009). Pagan Themes in Modern Children's Fiction: Green Man, Shamanism, Earth Mysteries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21839-0.

- Sandars, Nancy K., Prehistoric Art in Europe, Penguin (Pelican, now Yale, History of Art), 1968 (nb 1st edn.)

Further reading

- Amis, Kingsley. The Green Man, Vintage, London (2004) ISBN 0-09-946107-2 (Novel)

- Anderson, William. Green Man: The Archetype of our Oneness with the Earth, HarperCollins (1990) ISBN 0-00-599252-4

- Basford, Kathleen. The Green Man, D.S. Brewer (2004) ISBN 0-85991-497-6 (The first monograph on the subject, now reprinted in paperback)

- Beer, Robert. The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs Shambhala. (1999) ISBN 1-57062-416-X, ISBN 978-1-57062-416-2

- Cheetham, Tom. Green Man, Earth Angel: The Prophetic Tradition and the Battle for the Soul of the World , SUNY Press 2004 ISBN 0-7914-6270-6

- Doel, Fran and Doel, Geoff. The Green Man in Britain, Tempus Publishing Ltd (May 2001) ISBN 0-7524-1916-1

- Harding, Mike. A Little Book of the Green Man, Aurium Press, London (1998) ISBN 1-85410-563-9

- Hicks, Clive. The Green Man: A Field Guide, Compass Books (August 2000) ISBN 0-9517038-2-X

- MacDermott, Mercia. Explore Green Men, Explore Books, Heart of Albion Press (September 2003) ISBN 1-872883-66-4

- Matthews, John. The Quest for the Green Man, Godsfield Press Ltd (May 2004) ISBN 1-84181-232-3

- Neasham, Mary. The Spirit of the Green Man, Green Magic (December 2003) ISBN 0-9542963-7-0

- Varner, Gary R. The Mythic Forest, the Green Man and the Spirit of Nature, Algora Publishing (March 4, 2006) ISBN 0-87586-434-1

- The name of the Green Man Research paper by Brandon S Centerwall from Folklore magazine

External links

- Greenman Encyclopedia Wiki A site with a comprehensive listings of locations of Green Men in the UK