Forkhill/Forkill

| |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 550 (2021) |

| Irish grid reference | J013158 |

| • Belfast | 41 mi (66 km) |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | NEWRY |

| Postcode district | BT35 |

| Dialling code | 028, +44 28 |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly | |

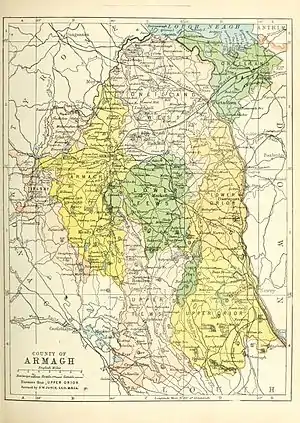

Forkhill or Forkill (/fɔːrkˈhɪl/ fork-HIL, /fɔːrˈkɪl/ for-KIL; from Irish Foirceal, meaning 'trough/hollow')[1] is a small village and civil parish in south County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It is within the Ring of Gullion and in the 2011 Census it had a recorded population of 498.[2] The population increased to 550 at the time of the 2021 Census. Forkhill was the settlement with the highest percentage of residents that identified as "Irish Only" in the 2021 census, 80.55%, 2.18% were "British Only". It lies within the former barony of Orior Upper.

Its name, deriving from the Irish word foirceal may refer to the village's position on flat land between the large hills of Tievecrom (to the east) and Croslieve (to the west).

History

The land in the parish was awarded by Elizabeth I to Capt. Thomas Chatterton and by James II to Lord Audley on condition of English settlement, but by 1659 it was still almost entirely occupied by native Irish people. Following the terms of a trust set up by a subsequent owner, Richard Jackson, much of the property was declared waste and resettled in 1787–91 with a view to encouraging the linen industry, most of the new settlers being Protestants. This was followed by serious breaches of the peace, which have been attributed not to sectarianism but by L. M. Cullen to political disputes among the gentry, and by David Millar to weakening social disciplines on the increasingly independent class of skilled linen weavers, both Protestant and Catholic.[3]

The Defenders emerged around Forkhill in the early 1790s, and were responsible in 1791 for an attack on the family of the local schoolmaster, Alexander Berkley, which was so savage as to be remembered with horror and indignation for over hundred years, both in the village and (although the Berkley attack was not provoked by sectarian motives) more widely across the Orange community.[4] Belmont, a military barracks, was set up in the parish in 1795, and a Forkhill Yeomanry in 1796; and a clash with United Irishmen in May 1797 along with the torching of Forkhill Lodge was followed by a policy of military terror which locally undermined the planned 1798 rising to the point of paralysis.[5]

1821 saw the first successful census of Forkhill. About 10% of the 7,063 inhabitants were Protestant; and between the denominations the average family size was identical at just over 5 persons, both employed servants in roughly equal proportions, and both were for the most part situated on small farms. In a national survey in 1835 three local residents responded for Forkhill: Rev. William Smith (Church of Ireland), Rev. Daniel O’Rafferty (Catholic) and Maj. Arthur A. Bernard (Resident Magistrate). They reported that most families were engaged in labouring work, often seeking seasonal jobs elsewhere in the UK, and women no longer worked in the linen trades; rents were £1 a year for a small cabin, or £2 if it had a potato garden. The 1851 census covered language, and found that about a third of the people in the barony spoke Irish (though almost all had at least some knowledge of English).[6]

Richard Jackson's will had provided for free schooling of a Protestant character for the poor children of the parish. In 1825 about a quarter of the parish children were enrolled, of whom about two-thirds were Catholic. Following an intensification of sectarian feeling in the 1820s, Fr Daniel O’Rafferty, the parish priest, applied in 1834 for a national school in the parish, which opened in Maphoner in August. Jackson's legacy also saw a dispensary set up in Forkhill in 1821, a two-storey building attended by a doctor, Samuel Walker, three days a week and for emergencies.[7]

In 1832 violent opposition to the system of tithes reached Forkhill and became associated with Ribbonism, continuing with a series of affrays, attacks and murders until the passage of the Tithe Rent Charge Act 1838 made the tithe payable by landlords.[8] However, this source of resentment soon became overtaken by issues of rent and security, with persistent claims for proper leases being refused in the early 1840s, the Forkhill Estate preferring to deal with tenants-in-chief who sublet on difficult terms, a system giving rise to widespread intimidation and violence without regard to religious affiliation. The famine of the late 1840s, when death and migration reduced the population of the parish by about a quarter, eventually reduced the pressure on land; but before long problems returned, and the nearly-successful assassination of the Killeavy magistrate Meredith Chambré on 20 January 1852 while leaving Forkhill village gave rise to a denunciation by Queen Victoria and the constitution of a Parliamentary Select Committee on Outrages. By the late 1850s pressure by the authorities and by the Catholic Church, the constitution of a petty sessions court in Forkhill, and the Irish Reform Act of 1850 which extended the franchise had all conspired to relieve the situation.[9]

Forkhill, along with the rest of South Armagh, would have been transferred to the Irish Free State had the recommendations of the Irish Boundary Commission been enacted in 1925.[10]

Sport

Forkhill is the home of Forkhill Peadar Ó Doirnín GAC, which is one of the oldest clubs in Armagh GAA, having been founded in 1888. The name of the Gaelic football club commemorates the 18th-century poet Peadar Ó Doirnín.[11]

Education

St. Oliver Plunkett's Primary School is the local primary school and, as of 2018, had over 130 pupils enrolled.[12]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Placenames NI - Forkill

- ↑ "Census 2011 - Headcount and Household Estimates for Settlements". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 3–16

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 21, 157

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 37–39

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 45–63, 80, 123

- ↑ Madden (2005), ch. 5, p. 124

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 88–100

- ↑ Madden (2005), pp. 101–120

- ↑ "Irish Boundary Commission Report". National Archives. 1925. p. 130.

- ↑ "Your Place And Mine - Armagh - Forkhill". bbc.co.uk. BBC. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ "St Oliver Plunkett PS (Forkhill)". eani.org.uk. Education Authority (Northern Ireland). Retrieved 3 July 2020.

Sources

- Madden, Kyla (2005). Forkhill Protestants and Forkhill Catholics, 1787–1858. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-015-7.