Fort Loudoun | |

Fort Loudoun (20th-century reconstruction) from the outside | |

| |

| Location | Vonore, Tennessee, South bank of Little Tennessee River, about 3/4 miles southeast of U.S. 411 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°35′45″N 84°12′13″W / 35.59583°N 84.20361°W |

| Area | 50 acres (200,000 m2)[1] |

| Built | 1756–1757 |

| Architect | John William G. De Brahm |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000729 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[2] |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1965[3] |

Fort Loudoun was a British fort located in what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. Constructed from 1756 until 1757 to help garner Cherokee support for the British at the outset of the French and Indian War, the fort was one of the first significant British outposts west of the Appalachian Mountains. The fort was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm, while its construction was supervised by Captain Raymond Demeré; the fort's garrison was commanded by Demeré's brother, Paul Demeré. It was named for the Earl of Loudoun, the commander of British forces in North America at the time.[4]

Relations between the garrison of Fort Loudoun and the local Cherokee inhabitants were initially cordial but soured in 1758 with hostilities between Cherokee fighters and Anglo-American settlers on the frontier in Virginia and South Carolina. After 16 Cherokee chiefs who were being held hostage at Fort Prince George were killed by the garrison on February 16, the Cherokee laid siege to Fort Loudoun on March 1760. The fort's garrison held out for several months, but diminishing supplies forced its surrender in August 1760. Hostile Cherokees attacked the fort's garrison at camp during its return to South Carolina, killing more than two dozen and taking most of the survivors prisoner. Many of them were ransomed.[4]

In retaliation, James Grant led a British expedition against the Middle Towns in North Carolina and Lower Towns in South Carolina. After the Cherokee sued for peace, a peace expedition was made to the Overhill country by Henry Timberlake.

Based on the detailed descriptions of the fort's design by De Brahm and Demeré, and excavations conducted by the Works Progress Administration, the facility was reconstructed in the 1930s. Additional work was supported by the Fort Loudoun Association and the Tennessee Division of Archaeology in the 1970s and 1980s. The fort was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1965. It was moved and reconstructed above the water levels of Tellico Lake, created in 1979. It is now the focus of Fort Loudoun State Historic Park.

Background

As early as 1708, British officials had discussed building a fort in Cherokee territory.[5] The Province of South Carolina considered trade with the Cherokee crucial but had struggled to regulate it because of the remoteness of most Cherokee towns, which were primarily in river valleys within the Appalachian Mountains of North and South Carolina, as well as the Province of Georgia. As British traders had frequently exploited the Cherokee, many of the Cherokee leaders had developed anti-British sentiments. The British believed that a fort and garrison would enable them to regulate the trade.[6]

Support for the fort increased considerably in 1743, with the appointment of James Glen as South Carolina's governor. Glen believed such a fort could also be a stepping stone to expand British control into the interior of the North American continent, where France had some colonies along the Mississippi and Ohio tributaries in Illinois Country, and south in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast.[6] The fort had some support among British officials, as it was the height of King George's War (1744–1748), and the French were threatening to expand into the area from their base at Fort Toulouse (in modern central Alabama). While many of the Cherokee in the Carolinas were initially cold to the idea, the Overhill Cherokee (i.e., the Cherokee living on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, in what is now Tennessee), who had been suffering attacks from French-backed rival tribes, invited South Carolina to build the fort in 1747.[6] Support for the fort faded at the end of the war, however.[5]

The outbreak in 1754 of the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War between France and Great Britain) revived British interest in the fort. The Cherokee were still allies of the British, but French influence within the tribe had grown considerably. A faction of the tribe based at Great Tellico had switched its support to the French. The Cherokee towns were highly decentralized, and their chiefs made independent alliances.

The British Crown provided the Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie with funds to construct a fort, but Dinwiddie gave an insignificant amount to Governor Glen for this purpose and spent most of the remainder on the Braddock Expedition in 1755.[5] After this expedition ended in disaster, Dinwiddie turned to the Cherokee for assistance in defending Virginia's frontier. The Cherokee agreed to provide 600 warriors, and in return, Virginia and South Carolina would construct a fort in the west to protect Cherokee families while the men were away fighting.[6]

Construction

The construction of the fort was to be a joint effort by Virginia and South Carolina. The party from South Carolina was hampered by bureaucratic delays, however, and the Virginians, led by Major Andrew Lewis, reached the Cherokee "mother town" of Chota in the Little Tennessee River valley on June 28, 1756, several weeks ahead of the party from the other colony.[5] Rather than wait, Lewis's party began work on a fort across the Little Tennessee River from Chota. This structure, known as the "Virginia Fort", was square in shape, measuring 105 feet (32 m) on each side, with walls consisting of earthen embankments topped by a 7-foot (2.1 m) palisade. Lewis's orders were simply to construct the fort, so after its completion in early August 1756, the Virginians returned home.[5]

Although Governor Glen's political foes ousted him in May 1756, his successor, William Henry Lyttelton, was committed to the fort's completion.[6] An advance party led by William Gibbs crossed the mountains and arrived at Great Hiwassee in early August. They reached Tomotley on August 6, 1756, where Gibbs stayed in the home of Cherokee Chief Attakullakulla.[6]

The main body, consisting of 80 British regulars commanded by Captain Raymond Demeré and two provincial companies of 60 men each, departed from Fort Prince George on the South Carolina frontier on September 21, 1756. Accompanied by 60 pack horses, the group made the roughly 100-mile (160 km) trek in ten days, arriving in Tomotley on October 1. They were greeted by Cherokee leader Old Hop and 200 Indians.[6] The task of moving the fort's 300-pound (140 kg) cannons over the mountains was accomplished by a contractor named John Elliott.[5] John Stuart, an officer who had accompanied the garrison, negotiated a purchase of corn from the Cherokee that helped the garrison avoid starvation.[6]

John William Gerard de Brahm, a German-born engineer who had overseen the repair of the fortifications of Charleston, was tasked with designing the fort. De Brahm and Demeré argued over the fort's location and design. Demeré favored a site selected earlier that year by a scout named John Pearson, but De Brahm rejected the site as too exposed. He favored a site further upstream that offered a commanding view of the river, but Demeré disagreed, saying the site lacked suitable land for the garrison to grow crops. Demeré reported that De Brahm, incensed, took out his pistol and offered it to Demeré to shoot him in the head.[5] The two eventually agreed on the current site of the fort, near the confluence with the Tellico River, as a compromise.[6]

Construction of the fort began on October 5, 1756. De Brahm's design was more elaborate than a typical frontier fort. It was diamond-shaped with bastions at the corners, each of which contained three cannons. As the fort was built on a hill slope, two of the bastions were atop the hill and two were closer to the bottom, with the walls sloping downward. The bastions were named for the King George II, the Queen of Great Britain, the Prince of Wales, and the Duke of Cumberland. The walls were 300 feet (91 m) in length and surrounded by a ditch a yard deep and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, which was planted with a honey locust hedge.[5]

Throughout November and December 1756, Demeré and De Brahm continued to squabble over the fort's design. Demeré disliked De Brahm's original design for outer and inner palisades and thought De Brahm's plans for two smaller auxiliary fortresses near the river were too complex. The two also disagreed on whether or not to discharge the provincials. De Brahm argued that the construction work was nearly complete and the provincials no longer needed, and Demeré disagreed, stating the fort was still uninhabitable. On December 24, 1756, De Brahm, stating the fort was essentially finished, abruptly left for South Carolina, drawing a strong rebuke from Demeré. The nonplussed Cherokees referred to De Brahm as "the warrior who ran away in the night."[5]

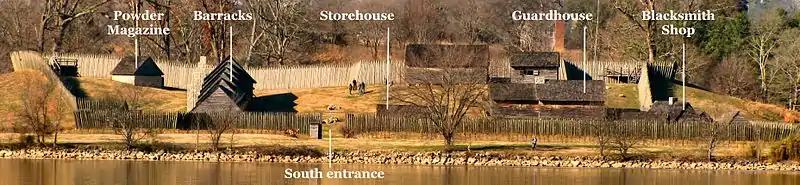

After De Brahm's departure, Demeré abandoned the original palisade design in favor of a single, more permanent palisade. The walls of the palisade consisted of 15-foot (4.6 m) upright logs, 8 feet (2.4 m) of which extended from the ground at a 15-degree angle. The interior of the fort covered approximately 2 acres (0.81 ha) and included a powder magazine, a blacksmith shop, barracks and officers' quarters, and supply buildings.[5] The garrison built drains, troughs for salting beef, a meathouse, and a charcoal pit for the blacksmith. The walls and bastions were completed by March 26, 1757. Demeré reported the fort completed on May 30, 1757.[5] Governor Lyttelton named the fort after John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, who had recently been appointed commander-in-chief of British forces in North America.[6]

Garrison

After reporting the fort completed, Demeré requested a replacement, saying that he had fallen ill. On August 6, 1757, his brother, Paul Demeré, arrived to relieve him, accompanied by reinforcements. By November 1757, the garrison had completed a guardhouse and several storage buildings. A personal house for Demeré was completed by early 1758,[5] and the fort's well was completed by June 1758. During the same period, the garrison planted 700 acres (280 ha) of crops.[6]

Life at the fort was generally routine. A changing of the guard took place several times per day. At night, five guard dogs roamed the fort's exterior. The fort's blacksmith spent much of his time mending Cherokee guns and tools. The garrison provided most of its own food through hunting, fishing and farming. Some food was acquired from the Cherokee (and some soldiers had Cherokee wives). Sixty women and children, dependents of the soldiers, lived in the fort.[5]

In June 1757, a 36-man contingent of the garrison, led by Lieutenant James Adamson and Ensign Richard Coytmore, attacked a band of hostile Indians who were threatening the Cherokee at Great Tellico. Three of the intruders were killed, and the rest were driven out.[6] In September 1757, Paul Demeré attended the Cherokees' Green Corn Dance and spent the subsequent months encouraging the Cherokee to launch attacks against the French and their Indian allies. He convinced a number of Cherokee, including Attakullakulla, to join the Forbes Expedition against Fort Duquesne in 1758 (Attakullakulla abandoned the expedition in disgust over Forbes' delays).[6]

William Richardson, a Presbyterian missionary (and uncle of future North Carolina Governor William Richardson Davie),[7] arrived at Fort Loudoun in late 1758.[6] He baptized a child of one of the soldiers and delivered sermons on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. He reported the Little Tennessee River had frozen over on December 19 and noted a persistent rumor of an impending French attack. Richardson said that the Cherokee were heavy drinkers who were not interested in his message about the Gospel. Frustrated, he left the fort on February 6, 1759.[6]

Anglo-Cherokee War

Relations between the Cherokee and the British began to decline in late 1758. During the Forbes Expedition, a group of Cherokee warriors, who had been tasked with fighting northern Indians who were allied with the French, scalped and killed one or more white settlers. They paraded the scalps before the British, deceptively claiming they belonged to their enemies in order to receive a promised bounty.[8] Suspicious, the British soldiers disarmed Attakullakulla and other warriors, none of whom had been involved, and briefly detained them. Although Virginia Leiutenant Governor Francis Fauquier managed to placate Attakullakulla, some Cherokee warriors, still bitter over this treatment, raided Virginia's frontier settlements while returning to the Tennessee Valley.[6] In response, the settlers killed several Cherokee, and the situation quickly spiraled out of control.[5] In April 1759, Moytoy of Citico led a raid into Virginia that killed several settlers. Both Demeré and Attakullakulla demanded the surrender of some of those responsible, but no Cherokee were given up.[6]

Fearing the situation would dissolve into open warfare, Governor Lyttelton placed an embargo on the sale of guns and ammunition to the Cherokee in August 1759. Several Cherokee, especially in Great Tellico and Citico, began turning to the French for weapons. In early September, a soldier from Fort Loudoun, an English merchant and British parkhorseman were killed and their scalps exchanged for French ammunition.[6]

After Demeré reported that the Cherokee were blocking roads into the Overhill country, Lyttelton began making preparations to march against the Cherokee in October 1759. At this time, a Cherokee delegation led by Oconostota arrived in Charleston to sue for peace. Skeptical of their intentions, Lyttelton ordered them held prisoner (ostensibly for their protection). He departed for Fort Prince George with 1,700 troops and the Cherokee captives, arriving on December 9, 1759. Shortly after his arrival, he negotiated a peace treaty with Attakullakulla, freeing Oconostota and several other Cherokee captives. He promised to release the remaining captives when the Cherokee who had killed white settlers were turned over.[6]

Oconostota and Attakullakulla returned to Fort Prince George in February 1760 to demand the release of the remaining hostages, but Richard Coytmore (who had replaced Lachlan McIntosh as commander of Fort Prince George's garrison) refused. On February 16 Oconostota requested a meeting with Coytmore. When Coytmore arrived at the meeting outside the fort, he was mortally wounded in an ambush orchestrated by Oconostota. The new commander ordered the hostages moved, which resulted in the panicked garrison killing them when a confrontation developed.[6]

Siege

Because of rising tensions, Demeré had begun preparing Fort Loudoun for a siege in September 1759. On September 9, after the Cherokee tried to drive away the fort's cattle, Demeré ordered the cattle to be brought inside the fort, where they were butchered and their meat salted for preservation.[6] In November John Stuart arrived with 70 reinforcements, increasing the fort's garrison to 200.[6] In January 1760, Demeré reported the fort had stockpiled enough meat for four months and enough corn for several weeks.[5]

Outraged by the killings at Fort Prince George, the Cherokee, led by Standing Turkey and Willenawah, launched an attack against Fort Loudoun on March 20, 1760.[6] The fort's cannons prevented them from getting close enough to inflict serious damage, however, and after firing on the fort for four days, the Cherokee settled in for a long siege.[5] In June 1760, a force of 1,300 British regulars led by Archibald Montgomerie destroyed several of the Lower Towns in South Carolina and invaded the Middle Towns in North Carolina, but after encountering stiff opposition at Etchoe Pass the force retreated to Charleston. During the same period, a force led by William Byrd III marched down the Holston River valley from Virginia with plans to relieve the fort, but their progress was very gradual.[5]

Attakullakulla, who remained on good terms with the garrison, was expelled from the Council at Chota for warning the garrison that Oconostota had planned a ruse to lure them out of the fort.[5] In early June 1760, Demeré reduced the rations to one quart of corn for three men.[6] In early July, the garrison ran out of bread and was forced to subsist on horse meat.[5] A dispatch in late July described the condition of the fort's garrison as "miserable beyond description."[6] News of Montgomerie's retreat further demoralized the garrison, and men began deserting. On August 6 Demeré called a council of war, which determined it was "impracticable to hold out any longer."[6] Stuart and James Adamson met with Oconostota and Standing Turkey at Chota to negotiate the fort's surrender. The fort, its cannon, and gunpowder would be turned over to the Cherokee, while the soldiers would be allowed to keep their personal arms and baggage.[6]

The flag was lowered at the fort for the final time on August 8, 1760, and the garrison set out for Fort Prince George the following day. They camped for the night at the mouth of Cane Creek, along the Tellico River near modern Tellico Plains. On the morning of August 10, some 700 Cherokee suddenly attacked the camp. The garrison briefly returned fire before surrendering. In the melee, three officers, twenty-three privates, and three women were killed. Demeré was reportedly forced to dance and had dirt stuffed in his mouth before he was executed. Stuart, the only officer to survive the assault, was ransomed by Attakullakulla. The remaining garrison and their families were taken captive. Most were ransomed in the ensuing months.[5]

Prior to leaving the fort, the garrison had buried several bags of gunpowder (in violation of the terms of surrender). This action has been suggested as a possible motive for the Cherokee attack at Cane Creek. But John Stevens, a member of the fort's garrison who survived the attack, suggested the Cherokee had planned the attack all along.[6]

Aftermath and later history

After receiving news of the fort's capture, Governor Kerlerec of Louisiana dispatched French ships into the interior in an attempt to occupy the fort, but the ships were unable to navigate up the Tennessee River.[6] In the summer of 1761, James Grant led an expedition that destroyed a dozen Lower and Middle towns.[9] Seeing their position as untenable, the Cherokee negotiated a peace treaty with Grant, which was signed on September 23, 1761.[6]

In November, Old Hop negotiated a peace treaty with Byrd's men at Long Island of the Holston.[10] Henry Timberlake and Thomas Sumter, soldiers in Byrd's expedition, visited the Overhill towns in 1761–62 as part of a peace mission. In his Memoirs, Timberlake noted that Fort Loudoun was in ruins.[11]

Settlers may have used salvaged stones from Fort Loudoun to construct the Tellico Blockhouse in the 1790s, an outpost located across the river from the fort. Louis Phillipe, the future King of France, visited the blockhouse while in exile in the United States in 1797 and noted that Fort Loudoun was mostly rubble and brush. He suggested the site of the fort had been poorly selected.[6] After the Cherokee relinquished control of the area with the signing of the Calhoun Treaty in 1819, ownership of the fort's ruins changed hands several times.[6]

Historian P.M. Radford published an article about the fort, Old Fort Loudoun, in 1897 and notes that all traces of the fort, with the exception of the well, had disappeared.[6] The following year, author Mary Noailles Murfree published a novel about the fort, The Story of Old Fort Loudon, which includes several drawings by illustrator Ernest Peixotto.[12] The Colonial Dames of America placed a marker at the site of the fort in 1917. In a 1925 article, "Fort Loudoun on the Little Tennessee," historian Philip Hamer suggests the fort's earthworks were still discernible.[6]

Archaeological work and reconstruction

The Fort Loudoun Association and the Works Progress Administration launched the "Fort Loudoun Restoration Project" in September 1935, with plans to reconstruct the fort based on historical and archaeological research. Excavations at the site, which began in February 1936, were supervised by Hobart S. Cooper. Cooper was advised by archaeologists William S. Webb and Thomas M.N. Lewis. Historians Samuel Cole Williams, Philip Hamer, and Mary Rothrock provided historical research, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provided engineering advice. These excavations determined the locations of the inner and outer palisades, the powder magazine, and the chimney bases of several structures.[6]

Beginning in 1955, a series of minor excavations were conducted by Ellsworth Brown, Director of the Fort Loudoun Association. These excavations attempted to determine the location of the fort's flagstaff, and explored a structure in the northern part of the fort thought to be Paul Demeré's quarters. Brown conducted further excavations in 1957 to explore the fort's eastern ("Rivergate") entrance.[6] The fort was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1965.[1][3]

The Fort Loudoun Association was one of several groups that opposed the Tennessee Valley Authority's proposed Tellico Dam at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River in the 1960s, as the fort would be flooded by the dam's reservoir. At a contentious public meeting on the proposed dam in 1964, judge Sue K. Hicks, the Fort Loudoun Association's president, engaged in a verbal confrontation with TVA Chairman Aubrey Wagner.[13] TVA eventually agreed to fund the raising of land and reconstruction of the fort on the site, above the water level. Because the flooding would submerge known historic and prehistoric sites, including several Cherokee towns, the agency funded a survey and extensive archaeological excavations in the valley.

The most extensive excavations were conducted from May 1975 through August 1976 and were led by Carl Kuttruff of the Tennessee Division of Archaeology.[5] Approximately 93% of the fort's interior was investigated by hand excavation during this period.[6] Researchers also investigated the area south of the fort, uncovering artifacts from the Archaic (7500 BC), Woodland, and Southern Appalachia Mississippian culture (1000-1500CE) periods. In addition they recovered items related to the historic Cherokee village of Tuskegee. It developed south of the fort in the late 1750s, but there was also an earlier site nearby known as Old Taskagi.[6]

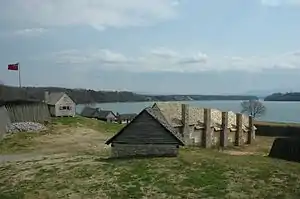

TVA provided 250,000 cubic yards of landfill to raise the site of the fort 8 metres (26 ft), bringing it above the reservoir's operating levels. Care was taken to preserve the original terrain and hillslope. Shortly after this was completed, the palisade, powder magazine, blacksmith shop, two troops quarters, a temporary barracks, a storehouse, one of the gun platforms, and a Cherokee house (representing Tuskegee) were reconstructed there. Artifacts from the excavations were placed on display inside the visitor's center.[6]

The location and purpose of several structures were determined through a combination of archaeological and historical work. A map of the fort drawn by De Brahm suggested the powder magazine was located in the northwest corner of the fort. It was in this area that excavators discovered evidence of the only structure in the fort built with stone walls, consistent with the design of contemporary powder magazines. Excavators uncovered what was likely an ash pit from a forge in the southeast corner of the fort, where De Brahm indicated the fort's blacksmith shop was located. A 1757 letter from Demeré indicated the fort's guardhouse had a double chimney. Excavators noted the only structure in the fort with a double chimney was an elongate building adjacent to the east gate, a position consistent with guardhouse placement at the time. A string of hearths in the western section of the fort indicated the location of the fort's barracks.[6]

State park and vicinity

The Fort Loudoun Association turned over ownership of the fort to the state in 1978 for establishment of a state park.[14] Fort Loudoun is now situated on an island created by Tellico Lake at the junction of the Little Tennessee and Tellico rivers. State Route 360 (Unicoi Turnpike) passes across the island, connecting the state park to Vonore to the north and the rural areas of Monroe County and the Cherokee National Forest to the south. The park's visitor center, which stands adjacent to the fort, contains a small museum with a model of the fort and several artifacts from the various excavations. Several miles of hiking trails meander through the woods around the fort, as well as in the McGhee-Carson Unit across the lake to the south.

The Cherokee scholar Sequoyah was born at Tuskegee, just south of the fort, circa 1770. The Sequoyah Birthplace Museum, which is operated by the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, stands just west of the fort, on the other side of Highway 360. The museum includes a burial mound containing over 200 burials excavated during the Tellico Archaeological Project. This had investigated several Cherokee town sites in anticipation of the flooding of the valley by Tellico Dam. Monuments to the Overhill towns of Tanasi and Chota, the "mother town" of the mid to late 18th century, are located along Bacon Ferry Road, just off Highway 360 about 12 miles (19 km) south of Fort Loudoun.

The site of the Tellico Blockhouse is located across the Little Tennessee River to the east of Fort Loudoun. The blockhouse and its associated structures were uncovered by researchers during the Tellico Archaeological Project and are now marked by wooden posts and stones. Several artifacts excavated from the blockhouse site are on display at the Fort Loudoun visitor center.

Legacy

Loudon County, Tennessee,[15] and its county seat, Loudon, are both named for the fort (Loudon County borders Monroe County to the north). The Tennessee Valley Authority's Fort Loudoun Dam, which stands to the north in Lenoir City, and its associated lake are also named for the fort. Other entities named for the fort include Fort Loudoun Electric Cooperative, a local electricity distributor; Fort Loudoun Medical Center in Lenoir City, and Fort Loudoun Middle School in Loudon.

See also

References

- 1 2 Polly M. Rettig and Horace J. Sheely Jr. (March 29, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Fort Loudoun" (pdf). National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying three photos, inside the reconstructed fort, from 1975 (32 KB) - ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- 1 2 "Fort Loudoun". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- 1 2 Carroll Van West, "Fort Loudoun," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 James C. Kelly, "Fort Loudoun: A British Stronghold in the Tennessee Country," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, Vol. 50 (1978), pp. 72-92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Carl Kuttruff, Beverly Bastian, Jenna Tedrick Kuttruff, and Stuart Strumpf, "Fort Loudoun in Tennessee: 1756-1760: History, Archaeology, Replication, Exhibits, and Interpretation Archived 2013-10-12 at Archive-It," Report of the Tennessee Wars Commission and Tennessee Division of Archaeology, Research Series No. 17 (Waldenhouse Publishers, Inc., 2010). Accessed at the Tennessee State Library and Archives website, 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Daniel Patterson, "Backcountry Legends of a Minister's Death," Southern Spaces, 30 October 2012. Retrieved: 16 December 2013.

- ↑ Letter to John Ross from Principal Chief Charles Renatus Hicks, dated July 15, 1825.

- ↑ John Finger, Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition (Indiana University Press, 2001), pp. 34-39.

- ↑ Henry Timberlake, Samuel Cole Williams (ed.), Memoirs, 1756-1765 (Marietta, Georgia: Continental Book Co., 1948), p. 38.

- ↑ Timberlake, Memoirs, p. 57.

- ↑ Charles Egbert Craddock (Mary Noailles Murfree), The Story of Old Fort Loudon (MacMillan, 1913).

- ↑ W. Bruce Wheeler, TVA and the Tellico Dam, 1936–1979: A Bureaucratic Crisis In Post-Industrial America (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1986), p. 64.

- ↑ Fort Loudoun Association homepage. Retrieved: 4 January 2014.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 191.