| Scapular fracture | |

|---|---|

| |

| A right sided scapula fracture with rib fractures underneath seen on a 3D reconstruction of a CT scan | |

| Specialty | Orthopedic |

A scapular fracture is a fracture of the scapula, the shoulder blade. The scapula is sturdy and located in a protected place, so it rarely breaks. When it does, it is an indication that the individual was subjected to a considerable amount of force and that severe chest trauma may be present.[1] High-speed vehicle accidents are the most common cause. This could be anywhere from a car accident, motorcycle crash, or high speed bicycle crash but falls and blows to the area can also be responsible for the injury. Signs and symptoms are similar to those of other fractures: they include pain, tenderness, and reduced motion of the affected area although symptoms can take a couple of days to appear. Imaging techniques such as X-ray are used to diagnose scapular fracture, but the injury may not be noticed in part because it is so frequently accompanied by other, severe injuries that demand attention. The injuries that usually accompany scapular fracture generally have the greatest impact on the patient's outcome. However, the injury can also occur by itself; when it does, it does not present a significant threat to life. Treatment involves pain control and immobilizing the affected area, and, later, physical therapy.

Signs and symptoms

As with other types of fractures, scapular fracture may be associated with pain localized to the area of the fracture, tenderness, swelling, and crepitus (the crunching sound of bone ends grinding together).[1] Since scapular fractures impair the motion of the shoulder, a person with a scapular fracture has a reduced ability to move the shoulder joint.[2] Signs and symptoms may be masked by other injuries that accompany the scapular fracture.[2]

Causes

Usually, it takes a large amount of energy to fracture the scapula; the force may be indirect but is more often direct.[3] The scapula is fractured as the result of significant blunt trauma, as occurs in vehicle collisions.[4] About three quarters of cases are caused by high-speed car and motorcycle collisions.[4] Falls and blows to the shoulder area can also cause the injury.[4] Crushing injuries (as may occur in railroad or forestry accidents) and sports injuries (as may occur in horseback riding, mountain biking, bmxing or skiing) can also fracture the scapula.[2] Scapular fracture can result from electrical shocks and from seizures: muscles pulling in different directions contract powerfully at the same time.[5] In cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the chest is compressed significantly; scapular fracture may occur as a complication of this technique.[4]

Anatomy

The scapula has a body, neck, and spine; any of these may be fractured. The most commonly injured areas are the scapular body, spine, neck, and glenoid rim; the scapular body or neck is injured in about 80% of cases. Fractures that occur in the body may be vertical, horizontal, or comminuted (involving multiple fragments). Those that occur in the neck are usually parallel to the glenoid fossa. When they occur in the glenoid fossa, fractures are usually small chips out of the bone or extensions of fractures occurring in the scapular neck.[4]

The scapula is protected from the front by the ribcage and chest, and from the back it is protected by a thick layer of muscles.[3] Also, the scapula is able to move, so traumatic forces exerted on it are dissipated, not absorbed by the bone.[3] Thus a large amount of force is required to fracture it.[4]

The scapula, on left.

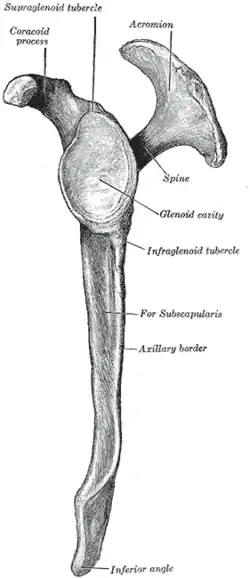

The scapula, on left. Lateral view of the left scapula

Lateral view of the left scapula

Diagnosis

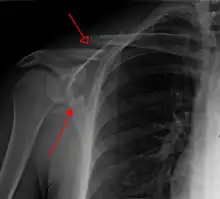

Most fractures of the scapula can be seen on a chest X-ray; however, they may be missed during examination of the film.[1] Serious associated injuries may distract from the scapular injury,[4] and diagnosis is often delayed.[3] Computed tomography may also be used.[1] Scapular fractures can be detected in the standard chest and shoulder radiographs that are given to patients who have had significant physical trauma, but much of the scapula is hidden by the ribs on standard chest X-rays.[4] Therefore, if scapular injury is suspected, more specific images of the scapular area can be taken.[4]

Classification

Body fractures

Described based upon anatomic location

Neck fractures

Coracoid process fractures

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Fracture proximal to the coracoclavicular ligament |

| II | Fracture distal to the coracoclavicular ligament |

Acromion fractures

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Non- or minimally-displaced |

| II | Displaced but not affecting the subacromial space |

| III | Displacement compromising the subacromial space |

Glenoid fossa fractures

Described by the Ideberg classification

Treatment

Treatment involves pain medication and immobilization at first; later, physical therapy is used.[1] Ice over the affected area may increase comfort.[6] Movement exercises are begun within at least a week of the injury; with these, fractures with little or no displacement heal without problems.[6] Over 90% of scapular fractures are not significantly displaced; therefore, most of these fractures are best managed without surgery.[3] Fractures of the scapular body with displacement may heal with malunion, but even this may not interfere with movement of the affected shoulder.[6] However, displaced fractures in the scapular processes or in the glenoid do interfere with movement in the affected shoulder if they are not realigned properly.[6] Therefore, while most scapular fractures are managed without surgery, surgical reduction is required for fractures in the neck or glenoid; otherwise motion of the shoulder may be impaired.[7]

Epidemiology

Scapular fracture is present in about 1% of cases of blunt trauma[1] and 3–5% of shoulder injuries.[4] An estimated 0.4–1% of bone fractures are scapular fractures.[2]

The injury is associated with other injuries 80–90% of the time.[1] Scapular fracture is associated with pulmonary contusion more than 50% of the time.[8] Thus when the scapula is fractured, other injuries such as abdominal and chest trauma are automatically suspected.[1] People with scapular fractures often also have injuries of the ribs, lung, and shoulder.[4] Pneumothorax (an accumulation of air in the space outside the lung), clavicle fractures, and injuries to the blood vessels are among the most commonly associated injuries.[4] The forces involved in scapular fracture can also cause tracheobronchial rupture, a tear in the airways.[9] Fractures that occur in the scapular body are the type most likely to be accompanied by other injuries; other bony and soft tissue injuries accompany these fractures 80–95% of the time.[3] Associated injuries can be serious and potentially deadly,[3] and usually it is the associated injuries, rather than the scapular fracture, that have the greatest effect on the outcome.[4] Scapular fractures can also occur by themselves; when they do, the death rate (mortality) is not significantly increased.[4]

The mean age of people affected is 35–45 years.[2]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Livingston DH, Hauser CJ (2003). "Trauma to the chest wall and lung". In Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL (eds.). Trauma. Fifth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 516. ISBN 0-07-137069-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wiedemann et al. (2000) pp. 504–507

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Goss TP, Owens BD (2006). "Fractures of the scapula: Diagnosis and treatment". In Iannotti JP, Williams GR (eds.). Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 794–795. ISBN 0-7817-5678-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Queiroz R, Sucov A (1999). "The clavicle and scapula". In Schwartz DM, Reisdorff E (eds.). Emergency Radiology. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division. pp. 117–134. ISBN 0-07-050827-5.

- ↑ Wiedemann et al. (2000) p. 504. "Scapular fractures may be caused by forceful contraction of divergent muscles elicited by a seizure or by electrical shock."

- 1 2 3 4 Wiedemann et al. (2000) p. 510

- ↑ Miller LA (March 2006). "Chest wall, lung, and pleural space trauma". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 44 (2): 213–24, viii. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2005.10.006. PMID 16500204.

- ↑ Allen GS, Coates NE (November 1996). "Pulmonary contusion: A collective review". The American Surgeon. 62 (11): 895–900. PMID 8895709.

- ↑ Hwang JC, Hanowell LH, Grande CM (1996). "Peri-operative concerns in thoracic trauma". Baillière's Clinical Anaesthesiology. 10 (1): 123–153. doi:10.1016/S0950-3501(96)80009-2.

References

- Wiedemann E, Euler E, Pfeifer K (2000). "Scapular fractures". In Wulker N, Mansat M, Fu FH (eds.). Shoulder Surgery: An Illustrated Textbook. Martin Dunitz. pp. 504–510. ISBN 1-85317-563-3.

External links

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (2007). Fracture of the shoulder blade (scapula). Retrieved on 2008-08-03.