A fuller is a rounded or beveled longitudinal groove or slot along the flat side of a blade (e.g., a sword, knife, or bayonet) that serves to both lighten and stiffen the blade, when considering its reduced weight.[1] However, cutting or grinding a fuller into an existing blade will decrease its absolute stiffness by a small amount due to the removal of material, but much of the strength remains due to the geometry of its shape. When the groove is forged into the blade, it achieves a similar reduction in weight with a relatively small reduction in strength without the wasted material produced by grinding (kerf). When forged, it is made using a blacksmithing tool that is also called a fuller, a form of a spring swage, or impressed during forging. When combined with proper distal tapers, heat treatment and blade tempering, a fullered blade can be 20% to 35% lighter than a non-fullered blade. The ridges and groove created by the fuller are comparable to an I-beam's flanges and web; this shape aims to optimize the strength and stiffness for a given quantity of material, particularly in the cutting direction.

A fuller is often used to widen a blade during smithing or forging. Fullers are sometimes inaccurately called blood grooves or blood gutters. Channelling blood is not the purpose of a fuller.[2][3][4]

Etymology

The term "fuller" is from the Old English fuliere, meaning 'one that fulls [pleats] cloth'. It is derived from the Latin word fullo. The first recorded use of the term in relation to metal working is 1587.[5] The first recorded use of the term to describe a groove or channel in a blade is 1967.[6]

Tool

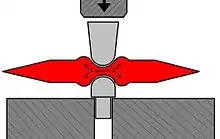

As a blacksmithing tool, a fuller is a type of swage, a tool with a cylindrical or beveled face used to imprint grooves into metal.

Fullers are typically three to six inches long. If a groove is to be applied to both sides of the steel, two fullers may be used at the same time, sandwiching the workpiece in the middle. Often, one fuller will have a peg that holds it securely in the anvil, while the other fuller will have a handle and a flat head, for striking with a hammer. A blade being fullered will generally be slowly pulled through the fullers as it is being hammered, displacing material to the side (rather than removing it) and thereby creating ridges on either side of a groove. These ridges may be hammered flat, widening the blade, or they are often shaped with other swages, increasing the strength of the blade both by creating thicker areas in its cross section and lateral ridges that resist lengthwise deflection.

In addition to being used to "draw out" steel, hammering a short block into a long bar, fullers are also used in the production of items such as hinges and latches, plow parts, and horseshoes.[7]

Japanese blades

In Japanese swordsmithing, fullers have a rich tradition and terminology, enough that there are separate terminologies for the top (hi, usually pronounced as bi when used as the second member of a compound) and bottom (tome) ends of the feature.

- Bo-hi (棒樋, ぼうひ): A continuous straight groove of notable width, known as katana-bi on tantō. With soe-bi (添樋, そえび), a secondary narrow groove follows the inner straight length of the main one. With tsure-bi (連樋, つれひ), the secondary is similar but continues beyond the straight length.

- Futasuji-hi (二筋樋, ふたすじひ): Two parallel grooves.

- Shobu-hi (菖蒲樋, しょうぶひ): A groove shaped like the leaf of an iris plant.

- Naginata-hi (薙刀樋, なぎなたひ): A miniature bo-hi whose top is oriented opposite from the blade's, and usually accompanied by a soe-bi. Seen primarily on naginatas.

- Kuichigai-hi (喰違樋, くいちがいひ): Two thin grooves that run the top half of the blade; the bottom half is denoted by the outer groove stopping halfway while the inner one expands to fill the width.

- Koshi-bi (腰樋, こしび): A short rounded-top groove found near the bottom of a blade, near to the tang.

- Tome

- Kaki-toshi (掻通し, かきとおし): The groove runs all the way down to the end of the tang.

- Kaki-nagashi (掻流し, かきながし): The groove tapers to a pointed end halfway down the tang.

- Kaku-dome (角止め, かくどめ): The groove stops as a square end within 3 cm of the tang's upper end.

- Maru-dome (丸止め, まるどめ): Similar to the kaku, except with a rounded-end.

The kukri

_with_Sheath_MET_36.25.831a_b_001_Apr2017.jpg.webp)

The Nepali kukri has a terminology of its own, including the "aunlo bal" (finger of strength/force/energy), a relatively deep and narrow fuller near the spine of the blade, which runs (at most) between the handle and the corner of the blade, and the "chirra", which may refer either to shallow fullers in the belly of the blade or a hollow grind of the edge, and of which two or three may be used on each side of the blade.[8]

Gallery

_(AM_697056-1).jpg.webp)

_(AM_697055-4).jpg.webp) Close-up view of a Pattern 1907 bayonet with hooked quillion

Close-up view of a Pattern 1907 bayonet with hooked quillion Fully fullered Imperial German S98/05 "Butcher Blade" bayonet

Fully fullered Imperial German S98/05 "Butcher Blade" bayonet Bayonet attached to the barrel of a British L85A2 rifle. Note the barrel to the left and slot in the blade to attach the wire-cutter scabbard

Bayonet attached to the barrel of a British L85A2 rifle. Note the barrel to the left and slot in the blade to attach the wire-cutter scabbard Bayonet for the Lee–Enfield Rifle No. 5 Mk I "Jungle Carbine"

Bayonet for the Lee–Enfield Rifle No. 5 Mk I "Jungle Carbine" US military bayonets; from the top down, they are the M1905, the M1, M1905E1 Bowie Point Bayonet (a cut down version of the M1905), and the M4 Bayonet for the M1 Carbine. The top 3 blades each have fullers

US military bayonets; from the top down, they are the M1905, the M1, M1905E1 Bowie Point Bayonet (a cut down version of the M1905), and the M4 Bayonet for the M1 Carbine. The top 3 blades each have fullers

See also

References

- ↑ Taste of History, "Dispelling Some Myths: 'Blood Grooves'"

- ↑ "Knife Encyclopedia; Blood Groove". A.G. Russell Knives. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ De Santis, Alessandra (13 May 2017). "Fuller". Ultimate Knives and Gear. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ von Brandt, Herr (1874). "The Ainos and Japanese". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 3: 135. doi:10.2307/2841072. JSTOR 2841072.

- ↑ Fuller. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ Neumann, George (1967). The History of Weapons of the American Revolution. Harper. p. 262. ASIN B006RUKZQQ.

- ↑ English Mechanic and World of Science: With which are Incorporated "the Mechanic", "Scientific Opinion," and the "British and Foreign Mechanic.". Vol. 54. E. J. Kibblewhite. 1892. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ↑ "Khukuri Construction and Technology". Himalayan Imports. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

Further reading

- Bealer, Alex W. (1976). The Art of Blacksmithing. Funk & Wagnalls. ISBN 978-0-308-10254-5. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Holmström, John Gustaf; Holford, Henry (17 September 2017). American Blacksmithing, Toolsmiths' and Steelworkers' Manual (Reprint ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-5285-7973-5. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

.jpg.webp)