In United States history, the gag rule was a series of rules that forbade the raising, consideration, or discussion of slavery in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1836 to 1844. They played a key role in rousing support for ending slavery.[1]: 274

Background

Congress regularly received petitions asking for various types of relief or action. Before the gag rules, House rules required that the first thirty days of each session of Congress be devoted to the reading of petitions from constituents. Each petition was read aloud, printed, and assigned to an appropriate committee, which could choose to address or ignore it. After those thirty days, petitions were read in the House every other Monday.

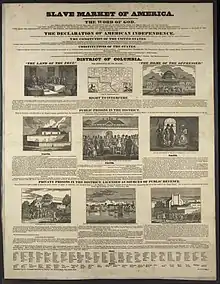

This procedure became unworkable in 1835, when, at the instigation of the new American Anti-Slavery Society, petitions arrived in Congress in quantities never before seen. Over the gag rule period, well over 1,000 petitions, with 130,000 signatures, poured into the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate praying for the abolition or the restriction of that allegedly beneficial "peculiar institution", as it was called in the South. There was a special focus on slavery in the District of Columbia, where policy was a federal, rather than state, matter. The petitions also asked Congress to use its Constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce to end the interstate slave trade, The petitions were usually presented by former president John Quincy Adams, who as a member of the House of Representatives from strongly anti-slavery Massachusetts, identified himself particularly with the struggle against any Congressional abridgement of the right of citizens to petition the government.[2]

The pro-slavery forces controlled Congress. The faction responded with a series of gag rules that, much to the disgust of Northerners, automatically "tabled" all such petitions, prohibiting them from being printed, read, discussed, or voted on. "The effect of these petitions was to create much irritation and ill feeling between different parts of the Union."[3]

Pinckney Resolutions (1836)

The House of Representatives passed the Pinckney Resolutions, authored by Henry L. Pinckney of South Carolina, on May 26, 1836. The first stated that Congress had no constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the states, and the second that it "ought not" to interfere with slavery in the District of Columbia. The third was known from the beginning as the "gag rule", and passed with a vote of 117 to 68:[4]

All petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions, or papers, relating in any way, or to any extent whatsoever, to the subject of slavery or the abolition of slavery, shall, without being either printed or referred, be laid on the table and...no further action whatever shall be had thereon.

From the inception of the gag resolutions, Adams was a central figure in the opposition to them. He argued that they were a direct violation of the First Amendment right "to petition the Government for a redress of grievances". A majority of Northern Whigs supported him. Rather than suppress anti-slavery petitions, however, the gag rules only served to outrage Americans from Northern states, contributing to the country's growing polarization over slavery.[5]: 112 The growing objection to the gag rule, as well as the Panic of 1837, may have contributed to the Whig majority in the 27th Congress, the party's first such majority.

Since the original gag was a resolution, not a standing House Rule, it had to be renewed every session, and Adams and others had free rein at the beginning of each session until this was done. In January 1837, the Pinckney Resolutions were substantially renewed, more than a month into the session. The pro-gag forces gradually succeeded in shortening the debate at the beginning of each session, and tightening the gag.

Attempt in United States Senate (1836)

Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina attempted to create a Senate gag rule in 1836. The Senate rejected this proposal, which pro-slavery senators thought would have the rebound (reverse) effect of strengthening the abolition movement. They agreed on a method which, while technically not a gag that violated the right to petition, had the same effect. If an anti-slavery petition were presented, the Senate would vote not on whether to accept the petition, but on whether to consider the question of accepting the petition.[6][7] The Senate never voted in favor of considering the acceptance of any petition.

Patton (1837) and Atherton (1838) gag rules

In December 1837, the Congress passed the Patton Resolutions, introduced by John M. Patton of Virginia. In December 1838, the Congress passed the Atherton gag, composed by Democratic "states' rights" Congressman Charles G. Atherton of New Hampshire, on the first petition day of the session.

Example of petitions presented on a single day (February 18, 1839)

- 53 men and 23 women, of Livingston County, New York, "remonstrating against the espionage in which the post office in Richmond, Virginia, and post offices in other places, are subjected, with the knowledge of the Postmaster General".

- 17 men of Lenox, New York, protesting the "mob violence" against Amos Dresser (Tennessee), Aaron W. Kitchell (Georgia),[8][9][10] and Elijah P. Lovejoy (Illinois); the "unlawful seizure and imprisonment for eight months" of Reuben Crandall; and that a Senator from South Carolina "declared...that, if any abolitionist come to that State, he would be hung [sic], despite any government on earth".

- Petitions for the recognition of Haiti from 405 men and women of St. Johnsbury, Vermont, 49 men of Northfield, Vermont, 96 men and women of Vershire, Vermont, 28 men of Walton, New York, 26 men of Williamsburg, New York, 194 men and women of Marlborough, New Hampshire, 52 men of Landaff, New Hampshire, 79 men and women of Belmont County, Ohio,[11] 204 men from various northeastern states.

- 9 petitions, from over 600 individuals, seeking the rescinding of the Atherton gag [see above]

- 58 petitions, from over 5,000 individuals, seeking:

- "The abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia,

- The abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia [to be prohibited by the Compromise of 1850],

- The prohibition of the slave trade between the states,

- The abolition of slavery in the Territory of Florida,

- The abolition of slavery and the slave trade in all the other territories of the United States,

- The refusal to admit any new slave state into the Union,

- The rejection of all propositions for the admission of Texas."[12]

From December 1838 to March 1839, the Twenty-Fifth Congress received "almost fifteen hundred petitions signed by more than one hundred thousand people. Eighty percent of the signatories supported abolition in the capital".[13]

Twenty-first rule (1840)

In January 1840, the House of Representatives passed the Twenty-first Rule, which greatly changed the nature of the fight: it prohibited even the reception of anti-slavery petitions and was a standing House rule. Before, the pro-slavery forces had to struggle to impose a gag before the anti-slavery forces got the floor. Now men like Adams or William Slade were trying to revoke a standing rule. However, it had less support than the original Pinckney gag, passing only by 114 to 108, with substantial opposition among Northern Democrats and even some Southern Whigs, and with serious doubts about its constitutionality. Throughout the gag period, Adams' "superior talent in using and abusing parliamentary rules" and skill in baiting his enemies into making mistakes, enabled him to evade the rule.

Repeal of the gag rule (1844)

The gag was finally rescinded on December 3, 1844, by a vote of 108–80, all the Northern and four Southern Whigs voting for repeal, along with 78% of the Northern Democrats.[5]: 476, 479–481 It was John Quincy Adams who wrote the repeal resolution and created the coalition necessary to pass it.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lerner, Gerda (1967). The Grimké Sisters From South Carolina. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-0321-9.

- ↑ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1906). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ↑ "Report of the Joint Committee on the Harpers Ferry Outrages, January 26, 1859 [sic]". Commonwealth of Virginia. January 26, 1860. Archived from the original on August 7, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ↑ von Holst, H. (1879). The Constitutional and Political History of the United States. Vol. 2. Chicago: Callaghan and Company. p. 245.

- 1 2 Miller, William Lee (1995). Arguing About Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-56922-9.

- ↑ Secretary of the United States Senate. "Gag rule". United States Senate. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ↑ Richards, Leonard L (1986). The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–50. ISBN 0-19-504026-0.

- ↑ Dupress, Ira E.; Tarver, H. H.; Bunn, Henry (November 5, 1836). "To the public". Augusta Chronicle. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- ↑ "Lynching a Jerseyman in Georgia". National Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). June 24, 1836. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- ↑ Yannielli, Joseph. "Princeton and Slavery". Princeton University. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ "Petitions peresented by Mr. Slade (1 of 2)". National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.). March 14, 1839. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- ↑ "Petitions peresented by Mr. Slade (2 of 2)". National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.). March 14, 1839. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- ↑ Morley, Jefferson (2013). Snow-storm in August : the struggle for American freedom and Washington's race riot of 1835. Anchor Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0307477484.

- ↑ Nagel, Paul C. John Quincy Adams: A Public Life, a Private Life. p. 359. 1999, Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- Holmes, Stephen (1988). "Gag Rules, or the Politics of Omission". In Elster, Jon; Slagstad, Rune (eds.). Constitutionalism and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–58. ISBN 0521345308.