Gare d'Orsay | |

|---|---|

| Heavy rail | |

1909 postcard: "La Gare d'Orleans (the Gare d'Orsay) et Quai d'Orsay" | |

| General information | |

| Location | Quai d'Orsay/Rue de Lille 75343 Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°51′37″N 2°19′31″E / 48.860283°N 2.325392°E |

| Owned by |

|

| Line(s) | Paris–Bordeaux railway |

| Tracks | 16 |

| Construction | |

| Architect | Victor Laloux |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| History | |

| Opened | 1900 |

| Closed | 1939 |

| Previous names | Gare d'Orleans (Quai d'Orsay) |

| Key dates | |

| 1986 | Reopened as the Musée d'Orsay |

| Location | |

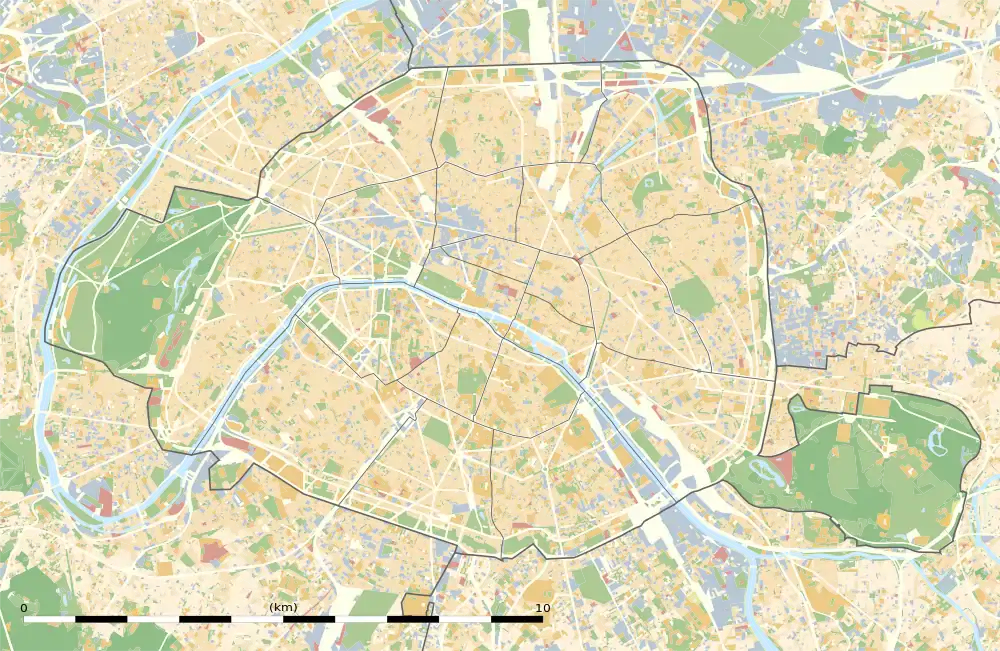

Gare d'Orsay Location of the Gare d'Orsay in Paris | |

Gare d'Orsay is a former Paris railway station and hotel, built in 1900 to designs by Victor Laloux, Lucien Magne and Émile Bénard; it served as a terminus for the Chemin de Fer de Paris à Orléans (Paris–Orléans Railway). It was the first electrified urban terminal station in the world, opened 28 May 1900, in time for the 1900 Exposition Universelle.[1] After closure as a station, it reopened in December 1986 as the Musée d'Orsay, an art museum. The museum is currently served by the RER station of the same name.

History

Palais d'Orsay

In the early 19th century, the site was occupied by a military barracks and the Palais d'Orsay, a governmental building originally built as for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The palace was erected over a period of 28 years, from 1810 to 1838, by the architects Jacques-Charles Bonnard and later Jacques Lacorné. After completion, the building was occupied by the Cour des Comptes and the Council of State.[2][3]

After the fall of the French Second Empire in 1870, the Paris Commune briefly took power from March to May 1871. The archives, library and works of art were removed to Palace of Versailles and eventually both the Conseil and the Cour des Comptes were rehoused in the Palais-Royal. On the night of 23–24 May 1871, the largely empty Palais d'Orsay was burned by the soldiers of the Paris Commune, along with the Tuileries Palace and several other public buildings associated with Napoleon III,[2] an event which was described by Émile Zola in his 1892 novel, La Débâcle. Following the fire, the burnt-out walls of the palace lay derelict for almost 30 years.[4][3]

Construction of the new station

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans (PO) railway company drew up plans to exploit the opportunities offered by the forthcoming Paris Exposition, which was due to open in 1900. The PO company's railway line from Orléans in southwestern France, opened in 1840, terminated at the Paris Gare d'Orléans station (later renamed Gare d'Austerlitz). The terminus was unfavourably located in the 13th arrondissement, and the PO Company sought to open extend its lines from Austerlitz into central Paris. In 1897, the company won government approval to construct a new terminus on the site of the former Palais d'Orsay. A 550 V DC third rail railway line extension was constructed in a 1 km (0.62 mi) cut-and-cover tunnel along the left bank of the Seine from Austerlitz to the Quai d'Orsay.[1][3]

The new terminal station, originally known as the Gare d'Orléans (Quai d'Orsay), was in a culturally sensitive location, surrounded by elegant buildings such as the Hôtel des Invalides, the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur and the Palais du Louvre. The PO company consulted three architects — Lucien Magne, Émile Bénard and Victor Laloux — to propose plans for a building that would be sympathetic to its surroundings. Laloux's scheme was successful, and the PO engaged him to design a monumental terminal station.[5][3] Laloux designed the new Gare d'Orsay in a Beaux-Arts style, facing it with large stone blocks and concealing the industrial aspects of the station behind ornate façades, decorated with large stone personification statues representing the railway destinations of Bordeaux, Toulon and Nantes.[6] The building included the 370-room Hotel Palais d'Orsay in the western and southern sides.[2]

The train shed was built as a steel and glass arch over the platforms and passenger concourse, with a span of 40 metres (130 feet) and measuring 138 metres (453 feet) in length and 32 metres (105 feet) wide over the 16 tracks. Passenger facilities incorporated many of the latest technological features, such as electric baggage lifts and escalators.[3]

The electric track system was modelled on the Baltimore Belt Line electrified railway which had been completed in 1895. Engineering was carried out by Compagnie Francaise Thomson-Houston SA, a French subsidiary of the General Electric Company (GE), and the electric locomotives were manufactured by GE with running gear by Alco.[1] The station design was the inspiration for the larger Penn Station in New York City when Alexander Cassatt, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, traveled on his annual trip to Europe in 1901.

The station opened to passenger traffic on 28 May 1900.[1][2]

Decline and closure

Advancements in the railways in the early 20th century led to the introduction of much longer mainline trains. Although the Gare d'Orsay offered a convenient central location, the site was restricted and there was no possibility of lengthening the platforms to accommodate the new, longer trains. The national rail operator SNCF was forced to terminate long-distance trains on the Orléans line at Gare d'Austerlitz and by 1939, the Gare d'Orsay had closed to long-distance traffic. The station continued to be served by suburban trains for some years afterwards.[7] The Hotel Palais d'Orsay closed at the beginning of 1973.

Although largely disused, the Gare d'Orsay came into use for some noteworthy events. During the Second World War, the former station was used as a collection point for the dispatch of parcels to prisoners of war, and in 1945, the station was used as a reception centre for liberated French prisoners of war on their return to France;[7] a plaque on the side of the building facing the River Seine commemorates this latter use. On 19 May 1958, General Charles de Gaulle used the opulent hotel ballroom for a press conference to announce his return to French national politics, ushering in the end of the French Fourth Republic.[7]

The empty Gare d'Orsay also served as a film location, providing the setting for several films, including Orson Welles's version of Franz Kafka's The Trial (1962), and is a central location in Bernardo Bertolucci's The Conformist (1970).

Line re-opening

The railway line terminating at Orsay was brought back into passenger service when a 1-kilometre (0.62 mi) extension was built in a tunnel along the bank of the Seine, connecting the PO line to the Gare des Invalides, the terminus of the former Chemins de fer de l'Ouest line to Versailles. A new Quai d'Orsay underground station was built (now the Musée d'Orsay station). The new link opened on 26 September 1979, and today forms part of Line C of the Parisian commuter rail system, the Réseau Express Régional (RER).[8][9]

Museum

In the 1960s, the appetite for replacing old buildings with modernist structures was gathering pace, and historic sites such as Les Halles market were being demolished. Plans were drawn up to demolish the Gare d'Orsay and replace it with a new building, and proposals for an airport, a government ministry building and a school of architecture were considered. Permission was granted to construct a hotel on the site, but in 1971 Jacques Duhamel, the minister of culture under President Georges Pompidou, intervened. The station building was in a sensitive location on the Seine facing the Tuileries Garden and the Louvre, and it was feared that a modern building would not fit in with the surrounding architecture. In 1973 the Gare d'Orsay was designated a protected Monument historique.[10]

At the time, the French Ministry of Culture was facing problems with a lack of exhibition space, particularly in the Musée du Jeu de Paume and the Louvre. With the opening of the Centre Pompidou in 1977 to house modern art, it was felt that there was a lack of provision for exhibiting art of the 19th century. The paintings curator of the Louvre, Michel Laclotte, proposed the creation of a new museum to display 19th century artworks from the Post-romanticism era up to Fauvism, and in particular the large collection of Impressionist art from the Jeu de Paume.[11]

The project to convert the disused railway station into a museum was announced in 1978 by President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing.[11] The architects for the conversion were the architects' firm ACT led by Pierre Colbloc.[12] The Italian architect Gae Aulenti developed the interior design of the gallery.[13] The building reopened as the Musée d'Orsay in December 1986. The former train shed now serves as the grand hall of the museum, with large works by sculptors such as Auguste Rodin, Jean-Joseph Perraud and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux on permanent display, overlooked by the large, ornate station clock. The former railway hotel now holds the paintings collection, displaying works by Georges Seurat, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh among others.[3]

| Dates | Company or line | Preceding station | Following station |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900–1937 | Chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans Paris–Bordeaux railway |

Terminus | Pont Saint-Michel |

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Baer, Christopher T. (March 2005). "PRR Chronology" (PDF). The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Schneider 1998, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Histoire du musée - Un musée dans une gare". www.musee-orsay.fr. Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ↑ Zola, Émile (1892). La Débâcle [The Downfall] (in French). Paris: Bibliothèque Charpentier. Part 3, chapter 8.

- ↑ Formentin, Charles, ed. (1897). "La Nouvell Gare d'Orléans". Le Magasin pittoresque (in French). Vol. 16, no. II. Ancienne Librairie Furne. pp. 108–110. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ↑ Schneider 1998, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Schneider 1998, p. 9.

- ↑ Pigenet, Michel (2008). Mémoires du travail à Paris: faubourg des métallos, Austerlitz-Salpêtrière, Renault-Billancourt (in French). creaphis editions. p. 150. ISBN 978-2-35428-014-7. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ↑ Janssoone ·, Didier (2019). Les 40 Ans de la Ligne C du RER 1979-2019 (La Vie du Rail). Paris: Éditions La Vie Du Rail.

- ↑ Schneider 1998, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 Schneider 1998, p. 12.

- ↑ Schneider 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Schneider 1998, p. 35.

Sources

- Schneider, Andrea Kupfer (1998). Creating the Musée d'Orsay: The Politics of Culture in France. State College, Pennsylvania: Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03834-6. Retrieved 24 June 2023.