| Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare | |

|---|---|

| Drafted | 17 June 1925[1] |

| Signed | 17 June 1925[1] |

| Location | Geneva[1] |

| Effective | 8 February 1928[1] |

| Condition | Ratification by 65 states[2] |

| Signatories | 38[1] |

| Parties | 146[3] |

| Depositary | Government of France[1] |

| Full text | |

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflicts. It was signed at Geneva on 17 June 1925 and entered into force on 8 February 1928. It was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on 7 September 1929.[4] The Geneva Protocol is a protocol to the Convention for the Supervision of the International Trade in Arms and Ammunition and in Implements of War signed on the same date, and followed the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

It prohibits the use of "asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids, materials or devices" and "bacteriological methods of warfare". This is now understood to be a general prohibition on chemical weapons and biological weapons between state parties, but has nothing to say about production, storage or transfer. Later treaties did cover these aspects – the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).

A number of countries submitted reservations when becoming parties to the Geneva Protocol, declaring that they only regarded the non-use obligations as applying to other parties and that these obligations would cease to apply if the prohibited weapons were used against them.[5][6]

Negotiation history

In the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, the use of dangerous chemical agents was outlawed. In spite of this, the First World War saw large-scale chemical warfare. France used tear gas in 1914, but the first large-scale successful deployment of chemical weapons was by the German Empire in Ypres, Belgium in 1915, when chlorine gas was released as part of a German attack at the Battle of Gravenstafel. Following this, a chemical arms race began, with the United Kingdom, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, and Italy joining France and Germany in the use of chemical weapons.[7]

This resulted in the development of a range of horrific chemicals affecting lungs, skin, or eyes. Some were intended to be lethal on the battlefield, like hydrogen cyanide, and efficient methods of deploying agents were invented. At least 124,000 tons were produced during the war. In 1918, about one grenade out of three was filled with dangerous chemical agents. Around 1.3 million casualties of the conflict were attributed to the use of gas, and the psychological effect on troops may have had a much greater effect.[7]

As protective equipment developed, the technology to destroy such equipment became a part of the arms race. The use of deadly poison gas was not only limited to combatants in the front but also civilians, as nearby civilian towns were at risk from winds blowing the poison gases through. Civilians living in towns rarely had any warning systems about the dangers of poison gas, as well as not having access to effective gas masks. The use of chemical weapons employed by both sides had inflicted an estimated 100,000-260,000 civilian casualties during the conflict. Tens of thousands or more, along with military personnel, died from scarring of the lungs, skin damage, and cerebral damage in the years after the conflict ended. In 1920 alone, over 40,000 civilians and 20,000 military personnel died from the chemical weapons effects.[7][8]

The Treaty of Versailles included some provisions that banned Germany from either manufacturing or importing chemical weapons. Similar treaties banned the First Austrian Republic, the Kingdom of Bulgaria, and the Kingdom of Hungary from chemical weapons, all belonging to the losing side, the Central powers. Russian bolsheviks and Britain continued the use of chemical weapons in the Russian Civil War and possibly in the Middle East in 1920.

Three years after World War I, the Allies wanted to reaffirm the Treaty of Versailles, and in 1922 the United States introduced the Treaty relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases in Warfare at the Washington Naval Conference.[9] Four of the war victors, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Italy and the Empire of Japan, gave consent for ratification, but it failed to enter into force as the French Third Republic objected to the submarine provisions of the treaty.[9]

At the 1925 Geneva Conference for the Supervision of the International Traffic in Arms the French suggested a protocol for non-use of poisonous gases. The Second Polish Republic suggested the addition of bacteriological weapons.[10] It was signed on 17 June.[11]

Historical assessment

Eric Croddy, assessing the Protocol in 2005, took the view that the historic record showed it had been largely ineffectual. Specifically it does not prohibit:[11]

- use against not-ratifying parties

- retaliation using such weapons, so effectively making it a no-first-use agreement

- use within a state's own borders in a civil conflict

- research and development of such weapons, or stockpiling them

In light of these shortcomings, Jack Beard notes that "the Protocol (...) resulted in a legal framework that allowed states to conduct [biological weapons] research, develop new biological weapons, and ultimately engage in [biological weapons] arms races".[6]

As such, the use of chemical weapons inside the nation's own territory against its citizens or subjects employed by Spain in the Rif War until 1927,[12][13] Japan against Seediq indigenous rebels in Taiwan (then part of the Japanese colonial empire) in 1930 during the Musha Incident, Iraq against ethnic Kurdish civilians in the 1988 attack on Halabja during the Iran–Iraq War, and Syria or Syrian opposition forces during the Syrian civil war did not breach the Geneva Protocol.[14]

Both the Syrian government and opposition forces accused each other of using chemical weapons in 2013 in Ghouta and Khan al-Assal during the Syrian civil war, though as any such use would be within Syria's own borders, rather than in warfare between state parties to the protocol, the legal situation is less certain.[15] A 2013 United Nations report confirmed the use of sarin, but did not investigate which side used chemical weapons.[16] In 2014, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons confirmed the use of chlorine gas in the Syrian villages of Talmanes, Al Tamanah and Kafr Zeta, but did not say which side used the gas.[17]

Despite the U.S. having been a proponent of the protocol, the U.S. military and American Chemical Society lobbied against it, causing the U.S. Senate not to ratify the protocol until 1975, the same year when the United States ratified the Biological Weapons Convention.[11][18]

Violations

Several state parties have deployed chemical weapons for combat in spite of the treaty. Italy used mustard gas against the Ethiopian Empire in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. In World War II, Germany employed chemical weapons in combat on several occasions along the Black Sea, notably in Sevastopol, where they used toxic smoke to force Russian resistance fighters out of caverns below the city. They also used asphyxiating gas in the catacombs of Odesa in November 1941, following their capture of the city, and in late May 1942 during the Battle of the Kerch Peninsula in eastern Crimea, perpetrated by the Wehrmacht's Chemical Forces and organized by a special detail of SS troops with the help of a field engineer battalion.[19] After the battle in mid-May 1942, the Germans gassed and killed almost 3,000 of the besieged and non-evacuated Red Army soldiers and Soviet civilians hiding in a series of caves and tunnels in the nearby Adzhimushkay quarry,[20] and Japan used chemical weapons in several instances against China during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

In the Second World War, the U.S., the UK, and Germany prepared the resources to deploy chemical weapons, stockpiling tons of them, but refrained from their use due to the ever-present fear of mutual retaliation. There was an accidental release of mustard gas in Bari, Italy causing many deaths when a U.S. ship carrying CW ammunition was sunk in the harbor during an air raid. After the war, thousands of tons of shells and containers with tabun, sarin and other chemical weapons were disposed of at sea by the Allies.

Early in the Cold War, the UK collaborated with the U.S. in the development of chemical weapons. The Soviet Union also had the facilities to produce chemical weapons but their development was kept secret.

During the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Iraq is known to have employed a variety of chemical weapons against Iranian forces, as well as nerve agents against Kurdish civilians, the most notorious example of which was the 1988 attack on Halabja. During the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Iraq is known to have employed a variety of chemical weapons against Iranian forces. Some 100,000 Iranian troops were casualties of Iraqi chemical weapons during the war.[21][22][23]

Subsequent interpretation of the protocol

In 1966, United Nations General Assembly resolution 2162B called for, without any dissent, all states to strictly observe the protocol. In 1969, United Nations General Assembly resolution 2603 (XXIV) declared that the prohibition on use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflicts, as embodied in the protocol (though restated in a more general form), were generally recognized rules of international law.[24] Following this, there was discussion of whether the main elements of the protocol now form part of customary international law, and now this is widely accepted to be the case.[18][25]

There have been differing interpretations over whether the protocol covers the use of harassing agents, such as adamsite and tear gas, and defoliants and herbicides, such as Agent Orange, in warfare.[18][26] The 1977 Environmental Modification Convention prohibits the military use of environmental modification techniques having widespread, long-lasting or severe effects. Many states do not regard this as a complete ban on the use of herbicides in warfare, but it does require case-by-case consideration.[27] The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention effectively banned riot control agents from being used as a method of warfare, though still permitting it for riot control.[28]

In recent times, the protocol had been interpreted to cover non-international armed conflicts as well international ones. In 1995, an appellate chamber in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia stated that "there had undisputedly emerged a general consensus in the international community on the principle that the use of chemical weapons is also prohibited in internal armed conflicts." In 2005, the International Committee of the Red Cross concluded that customary international law includes a ban on the use of chemical weapons in internal as well as international conflicts.[15]

However, such views drew general criticism from legal authors. They noted that much of the chemical arms control agreements stems from the context of international conflicts. Furthermore, the application of customary international law to banning chemical warfare in non-international conflicts fails to meet two requirements: state practice and opinio juris. Jillian Blake & Aqsa Mahmud cited the periodic use of chemical weapons in non-international conflicts since the end of WWI (as stated above) as well as the lack of existing international humanitarian law (such as the Geneva Conventions) and national legislation and manuals prohibiting using them in such conflicts.[29] Anne Lorenzat stated the 2005 ICRC study was rooted in "'political and operational issues rather than legal ones".[30]

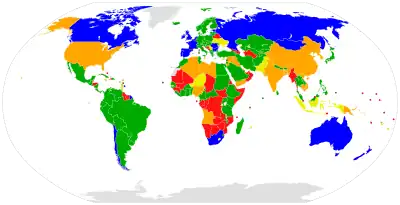

State parties

To become party to the Protocol, states must deposit an instrument with the government of France (the depositary power). Thirty-eight states originally signed the Protocol. France was the first signatory to ratify the Protocol on 10 May 1926. El Salvador, the final signatory to ratify the Protocol, did so on 26 February 2008. As of April 2021, 146 states have ratified, acceded to, or succeeded to the Protocol,[3] most recently Colombia on 24 November 2015.

Reservations

A number of countries submitted reservations when becoming parties to the Geneva Protocol, declaring that they only regarded the non-use obligations as applying with respect to other parties to the Protocol and/or that these obligations would cease to apply with respect to any state, or its allies, which used the prohibited weapons. Several Arab states also declared that their ratification did not constitute recognition of, or diplomatic relations with, Israel, or that the provision of the Protocol were not binding with respect to Israel.

Generally, reservations not only modify treaty provisions for the reserving party, but also symmetrically modify the provisions for previously ratifying parties in dealing with the reserving party.[18]: 394 Subsequently, numerous states have withdrawn their reservations, including the former Czechoslovakia in 1990 prior to its dissolution,[31] or the Russian reservation on biological weapons that "preserved the right to retaliate in kind if attacked" with them, which was dissolved by President Yeltsin.[32]

According to the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, states which succeed to a treaty after gaining independence from a state party "shall be considered as maintaining any reservation to that treaty which was applicable at the date of the succession of States in respect of the territory to which the succession of States relates unless, when making the notification of succession, it expresses a contrary intention or formulates a reservation which relates to the same subject matter as that reservation." While some states have explicitly either retained or renounced their reservations inherited on succession, states which have not clarified their position on their inherited reservations are listed as "implicit" reservations.

| Party[1][3][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41] | Signed[42] | Deposited | Reservations[1][18][34][35][43][44][45][46][47] | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 September 1986 | — | |||||

| 12 December 1989 | — | |||||

| 14 January 1992 |

|

|||||

| 30 October 1990 |

|

|||||

| 1 February 1989 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 8 May 1969 | — | |||||

| 13 March 2018 | — | |||||

| 22 January 1930 |

|

|||||

| 17 June 1925 | 9 May 1928 | — | ||||

| 9 November 1988 |

|

|||||

| 20 May 1989 |

|

|||||

| 16 July 1976 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 4 December 1928 |

|

||||

| 4 December 1986 | — | |||||

| 12 June 1978 | — | |||||

| 14 January 1985 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 28 August 1970 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 7 March 1934 |

|

||||

| 1 March 1971 | — | Ratified as the Republic of Upper Volta. | ||||

| 15 March 1983 | [Reservation 2] | The Protocol was ratified by the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea in exile in 1983. 13 states (including the depositary France) objected to their ratification, and considered it legally invalid. In 1993, the Kingdom of Cambodia stated in a note verbale that it considered itself bound by the provisions of the Protocol.[56] | ||||

| 21 April 1989 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 6 May 1930 |

|

||||

| 20 May 1991 | — | |||||

| 30 July 1970 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 2 July 1935 |

|

||||

| 7 August 1929 |

|

Ratified as the Republic of China, from which the People's Republic of China succeeded on 13 July 1952.[59] | ||||

| 24 November 2015 | — | |||||

| 17 June 2009 | — | |||||

| 27 July 1970 | — | |||||

| 25 September 2006 | — | |||||

| 24 May 1966 | — | |||||

| 29 November 1966 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 19 September 1993 |

|

Succeeded from Czechoslovakia, which ratified the protocol on 16 August 1938. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 5 May 1930 | — | ||||

| 4 December 1970 | — | |||||

| 10 September 1970 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 6 December 1928 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 12 January 2010 | — | ||||

| 16 May 1989 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 28 August 1931 |

|

||||

| 10 July 1991 | ||||||

| 17 June 1925 | 7 October 1935 | — | ||||

| 21 March 1973 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 26 June 1929 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 10 May 1926 |

|

||||

| 5 November 1966 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 25 April 1929 | — | ||||

| 2 May 1967 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 30 May 1931 | — | ||||

| 3 January 1989 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 3 May 1983 | — | |||||

| 20 May 1989 | — | |||||

| 12 October 1966 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 11 October 1952 | — | ||||

| 19 December 1966 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 9 April 1930 |

|

||||

| 14 January 1971 |

|

Succeeded from the Netherlands. | ||||

| 4 July 1929 | — | |||||

| 18 August 1931 |

|

|||||

| 18 August 1930 |

|

|||||

| 10 February 1969 |

|

|||||

| 17 June 1925 | 3 April 1928 | — | ||||

| 28 July 1970 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 21 May 1970 | — | ||||

| 20 January 1977 |

|

|||||

| 20 April 2020 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1970 | — | |||||

| 22 December 1988 |

|

|||||

| 29 December 1988 |

|

|||||

| 15 December 1971 |

|

|||||

| 29 June 2020 | — | |||||

| 16 January 1989 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 3 June 1931 | — | ||||

| 15 April 1969 | — | |||||

| 10 March 1972 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 2 April 1927 | — | |||||

| 21 December 1971 |

|

|||||

| 16 May 1991 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 15 June 1933 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 1 September 1936 | — | ||||

| 20 August 2015 | — | |||||

| 2 August 1967 | — | |||||

| 4 September 1970 | — | |||||

| 7 December 1970 | — | |||||

| 27 December 1966 | — | |||||

| 9 October 1970 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 23 December 1970 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 28 March 1932 | — | |||||

| 14 January 2011 | — | |||||

| 15 December 1966 | — | |||||

| 18 November 1968 |

|

|||||

| 7 October 1970 | — | |||||

| 7 May 1969 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 31 October 1930 |

|

||||

| 22 January 1930 |

|

|||||

| 17 June 1925 | 5 October 1990 | — | ||||

| 5 April 1967 |

|

Succeeded from France. | ||||

| 9 October 1968 |

|

|||||

| 17 June 1925 | 27 July 1932 | — | ||||

| 15 April 1960 |

|

Succeeded from India. | ||||

| 19 January 2018 | — | |||||

| 26 November 1970 | — | |||||

| 2 September 1980 |

|

Succeeded from Australia. | ||||

| 22 October 1933 | — | |||||

| 5 June 1985 | — | |||||

| 29 May 1973 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 4 February 1929 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 1 July 1930 |

|

||||

| 16 September 1976 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 23 August 1929 |

|

||||

| 17 June 1925 | 5 April 1928 |

|

Ratified as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. | |||

| 21 March 1964 |

|

Succeeded from Belgium. | ||||

| 26 October 1989 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 21 December 1988 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 23 April 1999 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 27 January 1971 | — | |||||

| 15 June 1977 | — | |||||

| 20 January 2003 |

|

Succeeded as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,[Note 2] which had ratified the protocol as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on 12 April 1929. | ||||

| 20 February 1967 | — | |||||

| 1 July 1997[Note 3] |

|

Succeeded from Czechoslovakia, which ratified the protocol on 16 August 1938. | ||||

| 8 April 2008 | — | |||||

| 1 June 1981 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 24 May 1930 |

|

|||||

| 17 June 1925 | 22 August 1929 |

|

||||

| 20 January 1954 | — | Ratified as the Dominion of Ceylon. | ||||

| 17 December 1980 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 25 April 1930 | — | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 12 July 1932 | — | ||||

| 17 December 1968 |

|

|||||

| 15 November 2019 | — | |||||

| 28 February 1963 | — | Ratified as the Republic of Tanganyika. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 6 June 1931 | —[Note 4] | Ratified as Siam. | |||

| 18 November 1970 | — | |||||

| 19 July 1971 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 24 November 1970 |

|

Succeeded from the United Kingdom. | ||||

| 12 July 1967 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 5 October 1929 | — | ||||

| 2 April 1965 | — | |||||

| 7 August 2003 |

|

Succeeded from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. | ||||

| 17 June 1925 | 9 April 1930 |

|

||||

| 17 June 1925 | 10 April 1975 |

|

||||

| 17 June 1925 | 12 April 1977 | — | ||||

| 5 October 2020 | — | |||||

| 17 June 1925 | 8 February 1928 | — | ||||

| 15 December 1980 |

|

|||||

| 11 March 1971 |

|

Ratified as the Yemen Arab Republic. Also ratified by the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen on 20 October 1986, prior to Yemeni unification in 1990.[89] |

- Reservations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Binding only with regards to states which have ratified or acceded to the protocol.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 Ceases to be binding in regards to any state, and its allies, which does not observe the prohibitions of the protocol.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Does not constitute recognition of, or establishing any relations with, Israel.

- 1 2 3 Ceases to be binding as to the use of chemical weapons in regards to any enemy state which does not observe the prohibitions of the protocol.

- ↑ Ceases to be binding in the case of a violation.

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 According to the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, states which succeed to a treaty after gaining independence from a state party "shall be considered as maintaining any reservation to that treaty which was applicable at the date of the succession of States in respect of the territory to which the succession of States relates unless, when making the notification of succession, it expresses a contrary intention or formulates a reservation which relates to the same subject matter as that reservation." Any state which has not clarified their position on reservations inherited on succession are listed as "implicit" reservations.

- ↑ Although the FR Yugoslavia claimed to be the continuator state of the SFR of Yugoslavia, the United Nations General Assembly did not accept this and forced them to reapply for membership.

- ↑ Listed as 28 October 1997 by the United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs.[80]

- ↑ Some sources list two reservations by Thailand, but neither the instrument of accession,[1] nor the United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs list,[85] makes any mention of a reservation.

- ↑ According to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, states may make a reservation when "signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty".

Non-signatory states

The remaining UN member states and UN observers that have not acceded or succeeded to the Protocol are:

Andorra

Andorra Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan Bahamas

Bahamas Belarus

Belarus Belize

Belize Bosnia

Bosnia Botswana

Botswana Brunei

Brunei Burundi

Burundi Chad

Chad Comoros

Comoros Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo Djibouti

Djibouti Dominica

Dominica Eritrea

Eritrea Gabon

Gabon Georgia

Georgia Guinea

Guinea Guyana

Guyana Haiti

Haiti Honduras

Honduras Kiribati

Kiribati Mali

Mali Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Mauritania

Mauritania Micronesia

Micronesia Montenegro

Montenegro Mozambique

Mozambique Myanmar

Myanmar Namibia

Namibia Nauru

Nauru Oman

Oman Palau

Palau Samoa

Samoa San Marino

San Marino São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe Seychelles

Seychelles Singapore

Singapore Somalia

Somalia South Sudan

South Sudan Suriname

Suriname Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Tuvalu

Tuvalu United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Vanuatu

Vanuatu Zambia

Zambia Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Chemical weapons prohibitions

| Year | Name | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 1675 | Strasbourg Agreement | The first international agreement limiting the use of chemical weapons, in this case, poison bullets. |

| 1874 | Brussels Convention on the Law and Customs of War | Prohibited the employment of poison or poisoned weapons (Never entered into force.) |

| 1899 | 1st Peace Conference at the Hague | Signatories agreed to abstain from "the use of projectiles the object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases." |

| 1907 | 2nd Peace Conference at the Hague | The Conference added the use of poison or poisoned weapons. |

| 1919 | Treaty of Versailles | Prohibited poison gas in Germany. |

| 1922 | Treaty relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases in Warfare | Failed because France objected to clauses relating to submarine warfare. |

| 1925 | Geneva Protocol | Prohibited the "use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids, materials or devices" and "bacteriological methods" in international conflicts. |

| 1972 | Biological and Toxins Weapons Convention | No verification mechanism, negotiations for a protocol to make up this lack halted by USA in 2001. |

| 1993 | Chemical Weapons Convention | Comprehensive bans on development, production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons, with destruction timelines. |

| 1998 | Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court | Makes it a war crime to employ chemical weapons in international conflicts. (2010 amendment extends prohibition to internal conflicts.) |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Protocole concernant la prohibition d'emploi à la guerre de gaz asphyxiants, toxiques ou similaires et de moyens bactériologiques, fait à Genève le 17 juin 1925" (in French). Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of France. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 21.

- 1 2 3 "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 94, pp. 66–74.

- ↑ "Disarmament Treaties Database: 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- 1 2 Beard, J. (2007). "The Shortcomings of Indeterminacy in Arms Control Regimes: The Case of the Biological Weapons Convention". American Journal of International Law. 101(2): 271–321. doi:10.1017/S0002930000030098. p., 277

- 1 2 3 D. Hank Ellison (24 August 2007). Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 567–570. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6.

- ↑ Max Boot (16 August 2007). War Made New: Weapons, Warriors, and the Making of the Modern World. Gotham. pp. 245–250. ISBN 978-1-5924-0315-8.

- 1 2 "Treaty relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases in Warfare. Washington, 6 February 1922". International Committee of the Red Cross. 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Geneva Protocol at 90, Part 1: Discovery of the dual-use dilemma - The Trench - Jean Pascal Zanders". 17 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Eric A. Croddy, James J. Wirtz (2005). Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology and History, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 140–142. ISBN 978-1851094905. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Pascal Daudin (June 2023). "The Rif War: A forgotten war?". International Review of the Red Cross.

- ↑ Noguer, Miquel (2 July 2005). "ERC exige que España pida perdón por el uso de armas químicas en la guerra del Rif". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ↑ "Geneva Protocol: Protocol For the Prohibition of the Use In War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous, or Other Gases, And of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare (Geneva Protocol)". Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- 1 2 Scott Spence and Meghan Brown (8 August 2012). "Syria: international law and the use of chemical weapons". VERTIC. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "U.N. confirms sarin used in Syria attack; U.S., UK, France blame Assad". 16 September 2013 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Syria chemical weapons: watchdog confirms Telegraph analysis of chlorine gas attacks on civilians". www.telegraph.co.uk. 10 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bunn, George (1969). "Banning Poison Gas and Germ Warfare: Should the United States Agree" (PDF). Wisconsin Law Review. 1969 (2): 375–420. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ Israelyan, Victor (1 November 2010). On the Battlefields of the Cold War: A Soviet Ambassador's Confession. Penn State Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0271047737.

- ↑ Merridale, Catherine, Ivan's War, Faber & Faber: pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Fassihi, Farnaz (27 October 2002), "In Iran, grim reminders of Saddam's arsenal", New Jersey Star Ledger, archived from the original on 13 December 2007, retrieved 27 July 2023

- ↑ Paul Hughes (21 January 2003), "It's like a knife stabbing into me", The Star (South Africa)

- ↑ Sciolino, Elaine (13 February 2003), "Iraq Chemical Arms Condemned, but West Once Looked the Other Way", The New York Times, archived from the original on 27 May 2013

- ↑ "2603 (XXIV). Question of chemical and bacteriological (biological) weapons" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 16 December 1969. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

use in international armed conflicts of: (a) Any chemical agents of warfare - chemical substances, whether gaseous, liquid or solid - which might be employed because of their direct toxic effects on man, animals or plants; (b) Any biological agents of warfare - living organisms, whatever their nature, or infective material derived from them - which are intended to cause disease or death in man, animals or plants, and which depend for their effects on their ability to multiply in the person, animal or plant attacked.

- ↑ Angela Woodward (17 May 2012). "The 1925 Geneva Protocol goes digital". VERTIC. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare (Geneva Protocol)". U.S. Department of State. 25 September 2002. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Practice Relating to Rule 76. Herbicides". International Committee of the Red Cross. 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Practice Relating to Rule 75. Riot Control Agents". International Committee of the Red Cross. 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Jillian Blake & Aqsa Mahmud (15 October 2013). "A Legal "Red Line"? Syria and the Use of Chemical Weapons in Civil Conflict". UCLA Law Review.

- ↑ Anne Lorenzat (2017–2018). "The Current State of Customary International Law with regard to the Use of Chemical Weapons in Non-International Armed Conflicts". The Military Law and the Law of War Review.

- ↑ "Czech Republic: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ Kelly, David (2002). "The Trilateral Agreement: lessons for biological weapons verification]" (PDF). In Findlay, Trevor; Meier, Oliver (eds.). Verification Yearbook 2002 (PDF). London: Verification Research, Training and Information Centre (VERTIC). pp. 93–109. ISBN 978-1-899548-35-4.

- ↑ "Le traité international en detail". Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- 1 2 "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare (Geneva Protocol)". United States Department of State. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare. Geneva, 17 June 1925". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "States parties to the Protocol for the prohibition of the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of bacteriological methods of warfare, Done at Geneva 17 June 1925". University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Protocol for the prohibition of the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of bacteriological methods of warfare". United Nations Treaty Series. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Protocol for the prohibition of the use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of bacteriological methods of warfare". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Protocole concernant la prohibition d'emploi à la guerre de gaz asphyxiants, toxiques ou similaires et de moyens bactériologiques". Government of Switzerland. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "Protocole du 17 juin 1925 concernant la prohibition d'emploi à la guerre de gaz asphyxiants, toxiques ou similaires et de moyens bactériologiques" (PDF). Government of Switzerland. 2004. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "Protocole concernant la prohibition d'emploi à la guerre de gaz asphyxiants, toxiques ou similaires et de moyens bactériologiques" (PDF). Government of Switzerland. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "No. 2138 - Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare. Signed at Geneva, 17 June 1925" (PDF). League of Nations Treaty Series - Publication of Treaties and International Engagements Registered with the Secretariat of the League of Nations. League of Nations. XCIV (1, 2, 3 and 4): 65–74. 1929. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Seventh BWC Review Conference Briefing Book" (PDF). Biological Weapons Convention. 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "High Contracting Parties to the Geneva Protocol". SIPRI. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ Schindler, Dietrich; Toman, Jiří (1988). The Laws of Armed Conflicts: A Collection of Conventions, Resolutions, and Other Documents. Brill Publishers. pp. 115–127. ISBN 9024733065. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Geneva Protocol reservations" (PDF). Biological Weapons Convention Review Conference. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ Papanicolopulu, Irini; Scovazzi, Tullio, eds. (2006). Quale diritto nei conflitti armati? (in Italian). Giuffrè Editore. pp. 231–237. ISBN 9788814130625. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Algeria: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Angola: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Australia: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ "Bahrain: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bangladesh: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Barbados: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Belgium: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bulgaria: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Cambodia: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Canada: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Chile: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- 1 2 "China: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Estonia: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fiji: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "France: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "India: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Iraq: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Ireland: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Israel: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Jordan: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Democratic People's Republic of Korea: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "Kuwait: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Libya: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Mongolia: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "Netherlands: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ "New Zealand: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Nigeria: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Papua New Guinea: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Romania: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Russian Federation: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Seventh Review Conference of Biological Weapons Convention" (PDF). 5 December 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑ Sims, Nicholas; Pearson, Graham; Woodward, Angela. "Article VII: Geneva Protocol Obligations and the BTWC" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Slovakia: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Solomon Islands: Succession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "South Africa: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Spain: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Syrian Arab Republic: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Thailand: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Ratification of 1925 Geneva". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "United States of America: Ratification of 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Viet Nam: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ "Yemen: Accession to 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

Further reading

- Frederic Joseph Brown (2005). "Chapter 3: The Evolution of Policy 1922-1939 / Geneva Gas Protocol". Chemical warfare: a study in restraints. Transaction Publishers. pp. 98–110. ISBN 1-4128-0495-7.

- Bunn, George. "Gas and germ warfare: international legal history and present status." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 65.1 (1970): 253+. online

- Webster, Andrew. "Making Disarmament Work: The implementation of the international disarmament provisions in the League of Nations Covenant, 1919–1925." Diplomacy and Statecraft 16.3 (2005): 551–569.

External links

- The text of the protocol Archived 7 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Weapons of War: Poison Gas