| Géza I | |

|---|---|

Géza depicted on the lower part, or Corona Graeca, of the Holy Crown of Hungary with the Greek inscription ΓΕΩΒΙΤΖΑϹ ΠΙΣΤΟϹ ΚΡΑΛΗϹ ΤΟΥΡΚΙΑϹ ("Géza, faithful king of the land of the Turks"). | |

| King of Hungary contested by Solomon | |

| Reign | 14 March 1074 – 25 April 1077 |

| Coronation | 1075, Székesfehérvár |

| Predecessor | Solomon |

| Successor | Ladislaus I |

| Born | c. 1040 Poland |

| Died | 25 April 1077 (aged 36–37) |

| Burial | Vác Cathedral |

| Spouse | Sophia Synadene |

| Issue | Coloman, King of Hungary Álmos |

| Dynasty | Árpád |

| Father | Béla I of Hungary |

| Mother | Richeza or Adelaide of Poland |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

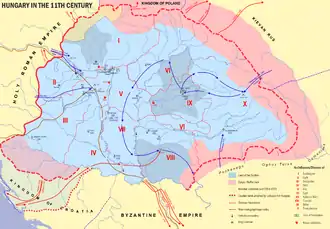

Géza I (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈɡeːzɒ]; Hungarian: I. Géza; c. 1040 – 25 April 1077) was King of Hungary from 1074 until his death. He was the eldest son of King Béla I. His baptismal name was Magnus. With German assistance, Géza's cousin Solomon acquired the crown when his father died in 1063, forcing Géza to leave Hungary. Géza returned with Polish reinforcements and signed a treaty with Solomon in early 1064. In the treaty, Géza and his brother Ladislaus acknowledged the rule of Solomon, who granted them their father's former duchy, which encompassed one-third of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Géza closely cooperated with Solomon, but their relationship became tense from 1071. The king invaded the duchy in February 1074 and defeated Géza in a battle. However, Géza was victorious at the decisive battle of Mogyoród on 14 March 1074. He soon acquired the throne, although Solomon maintained his rule in the regions of Moson and Pressburg (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia) for years. Géza initiated peace negotiations with his dethroned cousin in the last months of his life. Géza's sons were children when he died and he was succeeded by his brother Ladislaus.

Early years (before 1064)

Géza was the eldest son of the future King Béla I of Hungary and his wife Richeza or Adelhaid, a daughter of King Mieszko II of Poland.[1] The Illuminated Chronicle narrates that Géza and his brother Ladislaus were born in Poland, where their father who had been banished from Hungary settled in the 1030s.[1] Géza was born in about 1040.[1] According to the historians Gyula Kristó and Ferenc Makk, he was named after his grandfather's uncle Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians.[1] His baptismal name was Magnus.[2][3]

In about 1048, Géza's father returned to Hungary and received one third of the kingdom with the title of duke from his brother, King Andrew I.[4][5][6] Géza seems to have arrived in Hungary with his father.[6] The king, who had not fathered a legitimate son, declared Béla his heir.[7] According to the traditional principle of seniority, Béla preserved his claim to succeed his brother even after Andrew's wife Anastasia of Kiev gave birth to Solomon in 1053.[4][5] However, the king had his son crowned in 1057 or 1058.[1][8] The Illuminated Chronicle narrates that the child Solomon "was anointed king with the consent of Duke Bela and his sons Geysa and Ladislaus",[9] which is the first reference to a public act by Géza.[1] However, according to the contemporaneous text Annales Altahenses, Géza was absent from the meeting where Judith—the sister of the German monarch Henry IV—was engaged to the child Solomon in 1058.[10][11]

Géza accompanied his father, who left for Poland to seek assistance against King Andrew.[12] They returned with Polish reinforcements in 1060.[12][13] Géza was one of his father's most influential advisors. Lampert of Hersfeld wrote that Géza persuaded his father to set free Count William of Weimar, one of the commanders of the German troops fighting on Andrew's side, who had been captured in a battle.[12][14]

The king died during the civil war; his partisans took Solomon to the Holy Roman Empire and Géza's father Béla was crowned king on 6 December 1060.[4][15] Although Géza remained his father's principal advisor, King Béla did not grant his former duchy to his son.[12][16] According to the Annales Altahenses, Béla even offered Géza as hostage to the Germans when he was informed that the German court decided, in August 1063, to invade Hungary to restore Solomon.[17][18][19] However, the Germans refused Béla's offer and he died on 11 September 1063, some days after the imperial troops entered Hungary.[8][18][19]

Following his father's death, Géza offered to accept Solomon's rule if he received his father's former duchy.[19] This offer was refused, which forced him and his two brothers—Ladislaus and Lampert—to leave Hungary for Poland.[16][19] Duke Bolesław II of Poland provided them with reinforcements and they returned after the German troops were withdrawn from Hungary.[19][20] The brothers wanted to avoid a new civil war and made an agreement with King Solomon.[19][21] According to the treaty, which was signed in Győr on 20 January 1064, Géza and his brothers accepted Solomon's rule and the king granted them their father's duchy.[3][22] The king and his cousins celebrated Easter together in the cathedral of Pécs, where Duke Géza ceremoniously put a crown on Solomon's head.[23]

Being a newcomer and not yet established in his kingdom, King [Solomon] was afraid that [Géza] would perhaps attack him with a Polish army, and he therefore retired for a time with his forces and took up a safe station in the strongly fortified castle of [Moson]. The bishops and other religious men strove most earnestly to bring about a peaceful settlement between them. Especially bishop Desiderius softened Duke [Géza]'s spirit with his gentle admonitions and sweet pleadings that he should peaceably restore the kingdom to [Solomon], even though he was the younger, and should himself assume the dukedom which his father had held before him. [Géza] listened to his words of wise persuasion and laid aside his ill feeling. At [Győr], on the feast day of SS Fabian and Sebastian the martyrs, King [Solomon] and Duke [Géza] made peace with each other before the Hungarian people.

Duke in Hungary (1064–1074)

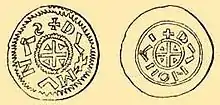

According to Ján Steinhübel and other Slovak historians, Géza only retained the administration of the region of Nyitra (present-day Nitra, Slovakia) and gave the eastern territories of their father's duchy, which were centered around Bihar (present-day Biharia, Romania), to his brother, Ladislaus.[3][21] The Hungarian historian Gyula Kristó likewise says that this division of Béla's one-time duchy is "probable".[23] The historians Gyula Kristó and Ferenc Makk write that Géza seems to have married a German countess named Sophia around this time.[2][25] Géza had the right to coinage in his duchy.[3] The silver half-denars minted for him bore the inscriptions DUX MAGNUS ("Duke Magnus") and PANONAI ("Kingdom of Hungary").[26]

Géza closely cooperated with the king between 1064 and 1071.[8] For instance, they jointly routed an invading army which had plundered the eastern territories of the kingdom at Kerlés (present-day Chiraleş, Romania) in 1068.[8][25] The identification of the invaders is uncertain: the Annales Posonienses writes of Pechenegs, the Illuminated Chronicle and other 14th- and 15th-century Hungarian chronicles refer to Cumans, and a Russian chronicle identifies them as Cumans and Vlachs.[27] Modern historians have concluded that they were Pechenegs.[27]

Géza's and Solomon's relationship only began to worsen during the siege of the Byzantine fortress of Belgrade in 1071.[8] Its commander preferred to surrender to Géza instead of the king and the Byzantine envoys who arrived in the Hungarian camp after the fall of Belgrade only negotiated with Géza.[28] The division of the booty also gave rise to a new conflict between Solomon and Géza.[8] Although Géza accompanied the king on a new campaign against the Byzantine Empire in 1072, his brother Ladislaus stayed behind with half of the troops of their duchy.[29][30]

The conflict between the king and his cousins was sharpened by Solomon's main advisor, Count Vid, who wanted to acquire the dukes' domains for himself.[25][31] However, Solomon and Géza, who were convinced that they needed foreign reinforcements before attacking the other party, concluded a truce which was to last from 11 November 1073 to 24 April 1075.[30][31] Géza sent his brothers to Poland and Rus' to seek assistance against Solomon.[31] At a meeting in the Szekszárd Abbey, Count Vid persuaded the king to break the truce in order to unexpectedly attack Géza who was "hunting in Igfan Forest"[32] to the east of the river Tisza.[30][31] Although the abbot of the monastery, which had been established by Géza's father, warned the duke of the king's plans, the royal army crossed the river and routed Géza's troops in the battle of Kemej on 26 February 1074.[30][31][33]

A legend preserved in the Illuminated Chronicle mentions that before the battle, Ladislaus "saw in broad daylight a vision from heaven" of an angel placing a crown on Géza's head.[34][35] Another legendary episode also predicted the dukes' triumph over the king: an "ermine of purest white" jumped from a thorny bush to Ladislaus's lance and then onto his chest.[34][36]

From the battlefield, Géza and his retinue hastened towards Vác where he came upon his brother Ladislaus and their brother-in-law, Duke Otto I of Olomouc.[33][37] The latter, accompanied by Czech reinforcements, arrived in Hungary in order to assist Géza against Solomon.[33][37] In the ensuing battle, fought at Mogyoród on 14 March 1074, Géza "with the troops from Nitria was stationed in the centre",[38] according to the Illuminated Chronicle.[33] During the battle, Géza and Ladislaus changed their standards in order to bewilder Solomon who was planning to attack Géza.[37] Géza and his allies won a decisive victory and forced the king to flee from the battlefield and to withdraw to Moson at the western frontier of Hungary.[33][37] Géza "made" Kapuvár, Babót, Székesfehérvár and "other castles secure with garrisons of the bravest soldiers",[39] thus taking possession of almost the entire kingdom.[33]

His reign (1074–1077)

Legend says that Géza decided to build a church dedicated to the Holy Virgin in Vác after Ladislaus explained the significance of the wondrous appearance of a red deer at the place where the church would be erected:[40]

As [King Géza and Duke Ladislaus] were standing at a spot near [Vác], where is now the church of the blessed apostle Peter, a stag appeared to them with many candles burning upon his horns, and it began to run swifly before them towards the wood, and at the spot where is now the monastery, it halted and stood still. When the soldiers shot their arrows at it, it leapt into the Danube, and they saw it no more. At this sight the blessed Ladislaus said: "Truly that was no stag, but an angel from God." And King [Géza] said: "Tell me, beloved brother, what may all the candles signify which we saw burning on the stag's horns." The blessed Ladislaus answered: "They are not horns, but wings; they are not burning candles, but shining feathers. It has shown to us that we are to build the church of the Blessed Virgin on the place where it planted its feet, and not elsewhere."

According to the Illuminated Chronicle, Géza accepted the throne "at the insistence of the Hungarians"[39] after Solomon had taken refuge in Moson.[28] However, he was not crowned because the royal jewels were still in the dethroned king's possession.[42] The German monarch Henry IV, who was Solomon's brother-in-law, launched an expedition against Hungary in mid-1074.[43][44] The Germans marched as far as Vác, but Géza applied scorched earth tactics and bribed German commanders, who persuaded the German monarch to retreat from Hungary.[44][45]

[Géza], hearing that the Emperor had come to Vacia, with prudent policy gave instructions to approach and win over the patriarch of Aquilegia, to whose counsels the Emperor most readily listened, and also all the [German] dukes, promising them much money if they would make the Emperor turn back. The patriarch, therefore, and the dukes, seduced by the gifts and possessed with love of gold, invented various false stories to induce the Emperor to turn back. The patriarch pretended that he had a dream whose interpretation most plainly was that the Emperor's army would be wholly destroyed by the divine vengeance unless he returned with the utmost speed. The dukes pretended likewise to be awestricken by divine warnings ...

In early 1074, Géza had approached Pope Gregory VII to obtain international recognition of his rule.[43] However, the pope wanted to take advantage of the conflict between Solomon and Géza and attempted to persuade both of them to acknowledge the suzerainty of the Holy See.[44] Géza did not obey the pope and asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael VII Doukas for a crown.[42] The emperor sent Géza a gold and enamel diadem, which bore the legend "Géza, the faithful king of Hungary" on one of its plaques.[47][48] This "splendid work of art"[22] became the lower part of the Holy Crown of Hungary by the end of the 12th century. Géza was crowned king with this diadem in early 1075.[49] In this year he styled himself as "anointed king of the Hungarians by the grace of God" in the charter of the foundation of the Benedictine Abbey of Garamszentbenedek (present-day Hronský Beňadik, Slovakia).[50]

Géza married a niece of Nikephoros Botaneiates, a close advisor of Emperor Michael VII.[51] However, Solomon still controlled Moson and Pressburg; the royal troops—which were under the command of Géza's brother, Ladislaus—could not take Pressburg in 1076.[49] According to the Illuminated Chronicle, Géza considered renouncing the crown in favor of Solomon from the end of the year.[52] Géza died on 25 April 1077 and was buried in the cathedral of Vác, which he had erected in honor of the Holy Virgin.[53][54] His brother Ladislaus succeeded him.[21] A grave discovered in the center of the medieval cathedral in August 2015 was identified as Géza's burial site by Zoltán Batizi, the leader of the excavations.[55]

[King Géza] celebrated Christmas at [Szekszárd]. ... When the Mass had been celebrated and all observances had been duly performed, the King instructed that all should leave except the bishop and the abbots. Then the King prostrated himself with tears before the Archbishop and the other ecclesiastical personages and prelates. He said that he had sinned because he had possessed himself of the kingdom of a lawfully crowned king; and he promised that he would restore the kingdom to [Solomon], and that these would be the conditions of firm peace between them: He would by lawful right hold the crown with that third part of the kingdom belonging with the duchy; the crowned [Solomon] would hold the two parts of the kingdom which he had held before. ... Then King [Géza] sent messengers to King [Solomon] with letters setting forth the terms of peace. Messengers passed to and fro, but feelings on this side and that were at variance, and so the reconciliation found no consummation. Meanwhile King [Géza] fell gravely ill, and on April 25, adorned with virtues, he went the way of all flesh. He was most devoted to God in the Catholic faith, and he was a most Christian Prince.

Family

| Ancestors of Géza I of Hungary[57][58] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Géza married twice.[59] The family of his first wife Sophia, whom he married in the late 1060s, is unknown.[25][60] After his coronation in 1075, he married his second wife, who was the niece of the future Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros III.[51] [60]

It is uncertain which wife bore Géza's children, but the historians Gyula Kristó and Márta Font say that Sophia was their mother.[25][61] Kristó adds that Géza fathered at least six children.[25] Although only two of them—Coloman and Álmos—are known by name, the Illuminated Chronicle states that Coloman had brothers who "died before him".[62][63] Both Coloman and Álmos were apparently born around 1070.[61]

The following family tree presents Géza's ancestors and some of his relatives who are mentioned in the article.[57]

| a lady of the Tátony clan | Vazul | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Andrew I | Béla I | Richeza or Adelaide | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Solomon | Sophia* | Géza | unnamed Synadene* | Ladislaus I | Lampert | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coloman | Álmos | 2–4 children** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kings of Hungary (till 1131) | Kings of Hungary (from 1131) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

*Whether Géza's first or second wife was his children's mother is uncertain.

**Géza had at least two further children, but their names are unknown.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 98.

- 1 2 Makk 1994, p. 235.

- 1 2 3 4 Steinhübel 2011, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Kontler 1999, p. 60.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 30.

- 1 2 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 79.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Engel 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 65.92), p. 115.

- ↑ Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Makk & Thoroczkay 2006, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 99.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 76.

- ↑ Makk & Thoroczkay 2006, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Bartl et al. 2002, p. 26.

- 1 2 Steinhübel 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Makk & Thoroczkay 2006, p. 80.

- 1 2 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 100.

- ↑ Manteuffel 1982, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Bartl et al. 2002, p. 27.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 61.

- 1 2 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 107.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 69–70.97), p. 117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 101.

- ↑ Steinhübel 2011, pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 Spinei 2009, p. 118.

- 1 2 Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 83.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 3 4 Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 85.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 80.114), p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Steinhübel 2011, p. 28.

- 1 2 Klaniczay 2002, p. 177.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 83.120), p. 123.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 85.121), p. 124.

- 1 2 3 4 Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 86.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 84.121), p. 124.

- 1 2 The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 87.124), p. 125.

- ↑ Klaniczay 2002, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 87–88.124), p. 125.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 32.

- 1 2 Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 102.

- ↑ Stephenson 2000, p. 188.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 90.128), p. 126.

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, p. 696.

- ↑ Stephenson 2000, pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 105.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 89.

- 1 2 Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 104.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 90.

- ↑ Kosztolnyik 1981, p. 92.

- ↑ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. 106.

- ↑ "Megtalálták I. Géza király sírhelyét" (in Hungarian). Múlt-Kor. 2005-08-19. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 92.130), p. 127.

- 1 2 Kristó & Makk 1996, pp. Appendices 1–2.

- ↑ Wiszewski 2010, pp. 29–30, 60, 376.

- ↑ Kristó & Makk 1996, p. Appendix 2.

- 1 2 Font 2001, p. 12.

- 1 2 Font 2001, p. 13.

- ↑ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 108.152), p. 133.

- ↑ Font 2001, pp. 12–13.

Sources

Primary sources

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary sources

- Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). "Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301 [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [=Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Font, Márta (2001). Koloman the Learned, King of Hungary. Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 963-482-521-4.

- Klaniczay, Gábor (2002). Holy Rulers and Blessed Princes: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42018-0.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kosztolnyik, Z. J. (1981). Five Eleventh Century Hungarian Kings: Their Policies and their Relations with Rome. Boulder. ISBN 0-914710-73-7.

- Kristó, Gyula; Makk, Ferenc (1996). Az Árpád-ház uralkodói [=Rulers of the House of Árpád] (in Hungarian). I.P.C. Könyvek. ISBN 963-7930-97-3.

- Makk, Ferenc (1994). "Géza I". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [=Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 235–236. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Makk, Ferenc; Thoroczkay, Gábor (2006). Írott források az 1050–1116 közötti magyar történelemről [=Written Sources of the Hungarian History between 1050 and 1116] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 978-963-482-794-8.

- Manteuffel, Tadeusz (1982). The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963–1194 (Translated and with an Introduction by Andrew Gorski). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1682-4.

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

- Steinhübel, Ján (2011). "The Duchy of Nitra". In Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (eds.). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–29. ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02756-4.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Wiszewski, Przemysław (2010). Domus Bolezlai: Values and Social Identity in Dynastic Traditions of Medieval Poland (c. 966–1138). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18142-7.

.svg.png.webp)